The lexical approach revisited

advertisement

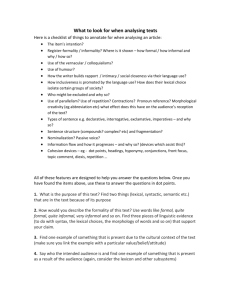

The lexical approach to second language teaching has received interest in recent years as an alternative to grammar-based approaches. The lexical approach concentrates on developing learners' proficiency with lexis, or words and word combinations. It is based on the idea that an important part of language acquisition is the ability to comprehend and produce lexical phrases as unanalyzed wholes, or "chunks," and that these chunks become the raw data by which learners perceive patterns of language traditionally thought of as grammar (Lewis, 1993, p. 95). Instruction focuses on relatively fixed expressions that occur frequently in spoken language, such as, "I'm sorry," "I didn't mean to make you jump," or "That will never happen to me," rather than on originally created sentences (Lewis, 1997a, p. 212). This digest provides an overview of the methodological foundations underlying the lexical approach and the pedagogical implications suggested by them. A NEW ROLE FOR LEXISMichael Lewis (1993), who coined the term lexical approach, suggests the following: * Lexis is the basis of language. * Lexis is misunderstood in language teaching because of the assumption that grammar is the basis of language and that mastery of the grammatical system is a prerequisite for effective communication. * The key principle of a lexical approach is that "language consists of grammaticalized lexis, not lexicalized grammar." * One of the central organizing principles of any meaning-centered syllabus should be lexis. TYPES OF LEXICAL UNITSThe lexical approach makes a distinction between vocabulary-traditionally understood as a stock of individual words with fixed meanings--and lexis, which includes not only the single words but also the word combinations that we store in our mental lexicons. Lexical approach advocates argue that language consists of meaningful chunks that, when combined, produce continuous coherent text, and only a minority of spoken sentences are entirely novel creations. The role of formulaic, many-word lexical units have been stressed in both first and second language acquisition research. (See Richards & Rodgers, 2001, for further discussion.) They have been referred to by many different labels, including "gambits" (Keller, 1979), "speech formulae" (Peters, 1983), "lexicalized stems" (Pawley & Syder, 1983), and "lexical phrases" (Nattinger & DeCarrico, 1992). The existence and importance of these lexical units has been discussed by a number of linguists. For example, Cowie (1988) argues that the existence of lexical units in a language such as English serves the needs of both native English speakers and English language learners, who are as predisposed to store and reuse them as they are to generate them from scratch. The widespread "fusion of such expressions, which appear to satisfy the individual's communicative needs at a given moment and are later reused, is one means by which the public stock of formulae and composites is continuously enriched" (p. 136). Lewis (1997b) suggests the following taxonomy of lexical items: * words (e.g., book, pen) * polywords (e.g., by the way, upside down) * collocations, or word partnerships (e.g., community service, absolutely convinced) * institutionalized utterances (e.g., I'll get it; We'll see; That'll do; If I were you ...; Would you like a cup of coffee?) * sentence frames and heads (e.g., That is not as ...as you think; The fact/suggestion/problem/danger was ...) and even text frames (e.g., In this paper we explore ...; Firstly ...; Secondly ...; Finally ...) Within the lexical approach, special attention is directed to collocations and expressions that include institutionalized utterances and sentence frames and heads. As Lewis maintains, "instead of words, we consciously try to think of collocations, and to present these in expressions. Rather than trying to break things into ever smaller pieces, there is a conscious effort to see things in larger, more holistic, ways" (1997a, p. 204). Collocation is "the readily observable phenomenon whereby certain words co-occur in natural text with greater than random frequency" (Lewis, 1997a, p. 8). Furthermore, collocation is not determined by logic or frequency, but is arbitrary, decided only by linguistic convention. Some collocations are fully fixed, such as "to catch a cold," "rancid butter," and "drug addict," while others are more or less fixed and can be completed in a relatively small number of ways, as in the following examples: * blood / close / distant / near(est) relative * learn by doing / by heart / by observation / by rote / from experience * badly / bitterly / deeply / seriously / severely hurt LEXIS IN LANGUAGE TEACHING AND LEARNINGIn the lexical approach, lexis in its various types is thought to play a central role in language teaching and learning. Nattinger (1980, p. 341) suggests that teaching should be based on the idea that language production is the piecing together of ready-made units appropriate for a particular situation. Comprehension of such units is dependent on knowing the patterns to predict in different situations. Instruction, therefore, should center on these patterns and the ways they can be pieced together, along with the ways they vary and the situations in which they occur. Activities used to develop learners' knowledge of lexical chains include the following: * Intensive and extensive listening and reading in the target language. * First and second language comparisons and translation--carried out chunk-for-chunk, rather than word-for-word--aimed at raising language awareness. * Repetition and recycling of activities, such as summarizing a text orally one day and again a few days later to keep words and expressions that have been learned active. * Guessing the meaning of vocabulary items from context. * Noticing and recording language patterns and collocations. * Working with dictionaries and other reference tools. * Working with language corpuses created by the teacher for use in the classroom or accessible on the Internet&mdashsuch as the British National Corpus (http://thetis.bl.uk/BNCbib) or COBUILD Bank of English (http://titania.cobuild.collins.co.uk)&mdashto research word partnerships, preposition usage, style, and so on. THE NEXT STEP: PUTTING THEORY INTO PRACTICEAdvances in computer-based studies of language, such as corpus linguistics, have provided huge databases of language corpora, including the COBUILD Bank of English Corpus, the Cambridge International Corpus, and the British National Corpus. In particular, the COBUILD project at Birmingham University in England has examined patterns of phrase and clause sequences as they appear in various texts as well as in spoken language. It has aimed at producing an accurate description of the English language in order to form the basis for design of a lexical syllabus (Sinclair, 1987). Such a syllabus was perceived by COBUILD researchers as independent and unrelated to any existing language teaching methodology (Sinclair & Renouf, 1988). As a result, the Collins COBUILD English Course (Willis & Willis, 1989) was the most ambitious attempt to develop a syllabus based on lexical rather than grammatical principles. Willis (1990) has attempted to provide a rationale and design for lexically based language teaching and suggests that a lexical syllabus should be matched with an instructional methodology that puts particular emphasis on language use. Such a syllabus specifies words, their meanings, and the common phrases in which they are used and identifies the most common words and patterns in their most natural environments. Thus, the lexical syllabus not only subsumes a structural syllabus, it also describes how the "structures" that make up the syllabus are used in natural language. Despite references to the natural environments in which words occur, Sinclair's (1987) and Willis's (1990) lexical syllabi are word based. However, Lewis's (1993) lexical syllabus is specifically not word based, because it "explicitly recognizes word patterns for (relatively) delexical words, collocation power for (relatively) semantically powerful words, and longer multi-word items, particularly institutionalized sentences, as requiring different, and parallel pedagogical treatment" (Lewis, 1993, p. 109). In his own teaching design, Lewis proposes a model that comprises the steps, Observe-Hypothesize-Experiment, as opposed to the traditional Present-Practice-Produce paradigm. Unfortunately, Lewis does not lay out any instructional sequences exemplifying how he thinks this procedure might operate in actual language classrooms. For more on implementing the lexical approach, see Richards & Rodgers (2001). CONCLUSIONZimmerman (1997, p. 17) suggests that the work of Sinclair, Nattinger, DeCarrico, and Lewis represents a significant theoretical and pedagogical shift from the past. First, their claims have revived an interest in a central role for accurate language description. Second, they challenge a traditional view of word boundaries, emphasizing the language learner's need to perceive and use patterns of lexis and collocation. Most significant is the underlying claim that language production is not a syntactic rulegoverned process but is instead the retrieval of larger phrasal units from memory. Nevertheless, implementing a lexical approach in the classroom does not lead to radical methodological changes. Rather, it involves a change in the teacher's mindset. Most important, the language activities consistent with a lexical approach must be directed toward naturally occurring language and toward raising learners' awareness of the lexical nature of language. REFERENCESCowie, A. P. (Eds.). (1988). Stable and creative aspects of vocabulary use. In R. Carter & M. McCarthy (Eds.), "Vocabulary and language teaching" (pp. 126-137). Harlow: Longman. Keller, E. (1979). Gambits: Conversational strategy signals. "Journal of Pragmatics, 3," 219237. Lewis, M. (1993). "The lexical approach: The state of ELT and the way forward." Hove, England: Language Teaching Publications. Lewis, M. (1997a). "Implementing the lexical approach: Putting theory into practice." Hove, England: Language Teaching Publications. Lewis, M. (1997b). Pedagogical implications of the lexical approach. In J. Coady & T. Huckin (Eds.), "Second language vocabulary acquisition: A rationale for pedagogy" (pp. 255270). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Nattinger, J. (1980). A lexical phrase grammar for ESL."TESOL Quarterly, 14," 337-344. Nattinger, J., & DeCarrico, J. (1992). "Lexical phrases and language teaching." Oxford: Oxford University Press. Pawley, A., & Syder, F. (1983). Two puzzles for linguistic theory: Native-like selection and native-like fluency. In J. Richards & R. Schmidt (Eds.), "Language and communication" (pp. 191-226). London: Longman. Peters, A. (1983). "The units of language acquisition." Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Richards, J., & Rodgers, T. S. (2001). "Approaches and methods in language teaching: A description and analysis" (2nd ed.). New York: Cambridge University Press. Sinclair, J. M. (Ed.). (1987). "Looking up: An account of the COBUILD project in lexical computing." London: Collins COBUILD. Sinclair, J. M., & Renouf, A. (Eds.). (1988). A lexical syllabus for language learning. In R. Carter & M. McCarthy (Eds.), "Vocabulary and language teaching" (pp. 140-158). Harlow: Longman. Willis, D. (1990). "The lexical syllabus: A new approach to language teaching." London: Collins COBUILD. Willis, J., & Willis, D. (1989). "Collins COBUILD English course." London: Collins COBUILD. Zimmerman, C. B. (1997). Historical trends in second language vocabulary instruction. In J. Coady & T. Huckin (Eds.), "Second language vocabulary acquisition: A rationale for pedagogy" (pp. 5-19). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Principles and implications of the Lexical Approach The Lexical Approach develops many of the fundamental principles advanced by proponents of the Communicative Approach. The most important difference is the increased understanding of the nature of lexis in naturally occurring language, and its potential contribution to language pedagogy. Key principles Language consists of grammaticalised lexis, not lexicalised grammar. The grammar/vocabulary dichotomy is invalid; much language consists of multiwords 'chunks'. A central element of language teaching is raising students' awareness of, and developing their ability to 'chunk' language successfully. Although structural patterns are known as useful, lexical and metaphorical patterning are accorded appropriate status. Collocation is integrated as an organising principle within syllabuses. The central metaphor of language is holistic - an organism; not atomistic - a machine. It is the co-textual rather than the situational element of context which are of primary importance for language teaching. Grammar as a receptive skill, involving the perception of similarity and difference, is prioritised. Receptive skills, particularly listening, are given enhanced status. The Present-Practise-Produce paradigm is rejected, in favour of a paradigm based on the Observe-Hypothesise-Experiment cycle. Contemporary language teaching methods tend to be similar for students at different level of competence; with the Lexical Approach the materials and methods appropriate to beginners or elementary students are radically different from those employed for upper-intermediate or advanced students. Significant re-ordering of the learning programme is implicit in the Lexical Approach. Lexical Approach 2 - What does the lexical approach look like? Submitted by TE Editor on 1 July, 2003 - 12:00 Share on facebookShare on twitter This article looks at the theories of language which form the foundations of the lexical approach to teaching English. Introduction The theory of learning Noticing Language awareness About the authors Further Reading Introduction The principles of the Lexical Approach have been around since Michael Lewis published 'The Lexical Approach' 10 years ago. It seems, however, that many teachers and researchers do not have a clear idea of what the Lexical Approach actually looks like in practice. In the first of our two THINK articles - Lexical approach 1 - we looked at how advocates of the Lexical Approach view language. In this, our second THINK article, we apply theories of language learning to a Lexical Approach and describe what lexical lessons could look like. We have also produced two TRY pieces containing teaching materials for you to try out in your own classrooms. Your feedback, opinions, comments and suggestions would be more than welcome and used to form the basis of a future article. A theory of learning In our first THINK article, Lexical Approach 1, we spoke about the vast number of chunks and collocations native speakers store. According to Lewis (1997, 2000) native speakers carry a pool of hundreds of thousands, and possibly millions, of lexical chunks in their heads ready to draw upon in order to produce fluent, accurate and meaningful language. Too many items for teachers and materials to present to learners, ask learners to practise and then produce even if you believed that a PPP methodology - which has been denigrated in recent years would lead to the acquisition of these language items. How then are the learners going to learn the lexical items they need? One of the criticisms levelled at the Lexical Approach is its lack of a detailed learning theory. It is worth noting, however, that Lewis (1993) argues the Lexical Approach is not a break with the Communicative Approach, but a development of it. He makes a helpful summary of the findings from first language acquisition research which he thinks are relevant to second language acquisition: Language is not learnt by learning individual sounds and structures and then combining them, but by an increasing ability to break down wholes into parts. Grammar is acquired by a process of observation, hypothesis and experiment. We can use whole phrases without understanding their constituent parts. Acquisition is accelerated by contact with a sympathetic interlocutor with a higher level of competence in the target language. Schmitt (2000) makes a significant contribution to a learning theory for the Lexical Approach by adding that 'the mind stores and processes these [lexical] chunks as individual wholes.' The mind is able to store large amounts of information in long-term memory but its short-term capacity is much more limited, when producing language in speech for example, so it is much more efficient for the brain to recall a chunk of language as if it were one piece of information. 'Figment of his imagination' is, therefore, recalled as one piece of information rather than four separate words. In our view it is not possible, or even desirable, to attempt to 'teach' an unlimited number of lexical chunks. But, it is beneficial for language learners to gain exposure to lexical chunks and to gain experience in analyzing those chunks in order to begin the process of internalisation. We believe, like Lewis, that encouraging learners to notice language, specifically lexical chunks and collocations, is central to any methodology connected to a lexical view of language. Noticing Batstone (1996) describes noticing as 'a complex process: it involves the intake both of meaning and form, and it takes time for learners to progress from initial recognition to the point where they can internalize the underlying rule'. At the same time Lewis (2000) argues that noticing chunks and collocations is a necessary but not sufficient condition for input to become intake. If learners are not directed to notice language in a text there exists a danger that they will 'see through the text' and therefore fail to achieve intake. Looking back at the tasks and activities in our TRY materials, you can see they are designed to promote noticing. Sometimes the noticing is guided by the teacher i.e. the teacher directs the students' attention to lexical features thought to be useful; sometimes the noticing is 'selfdirected', i.e. the students themselves select features they think will be useful for them. Sometimes the noticing is explicit, e.g. when items in a text are highlighted; sometimes it is implicit e.g. when the teacher reformulates a student's text (see Thornbury 1997 for an explanation of how reconstruction and reformulation can enhance noticing and practical suggestions for reformulating). Language Awareness It is our assertion that learning materials and teachers can best help learners achieve noticing of lexical chunks by combining a Language Awareness approach to learning with a Lexical Approach to describing language. Tomlinson (2003) sums up the principles, objectives and procedures of a language awareness approach as: 'Paying deliberate attention to features of language in use can help learners to notice the gap between their own performance in the target language and the performance of proficient users of the language. Noticing can give salience to a feature, so that it becomes more noticeable in future input, so contributing to the learner's psychological readiness to acquire that feature. The main objective is to help learners to notice for themselves how language is typically used so that they will note the gaps and 'achieve learning readiness' [as well as independence from the teacher and teaching materials]. The first procedures are usually experiential rather than analytical and aim to involve the learners in affective interaction with a potentially engaging text. [That is, learners read a text, and respond with their own views and opinions before studying the language in the text or answering comprehension type questions.] Learners are later encouraged to focus on a particular feature of the text, identify instances of the feature, make discoveries and articulate generalizations about its use.' In a small research project at The University of Maine, groups of students were exposed to materials (see TRY 1) based on the principles and procedures Tomlinson outlines. The noticing activities asked students to identify, analyse and make generalisations about lexical chunks and collocations. The students involved in the research were surveyed after using these materials and asked how useful and enjoyable they found the materials. All but one of the students said the materials were very useful and all the students reported the class was either very useful or useful. All the students said the materials would help them learn independently. Over half the students thought the materials were useful for learning vocabulary. All the students said they enjoyed the stories. The teachers said that the readings were 'great', the students understood and could appreciate the materials' relevance for developing reading as well a productive skills. One teacher said he was not sure if making the distinction between different types of lexical chunks was necessary. We hope these THINK articles and TRY materials shine some light on what a Lexical Approach could look like in teaching materials and provide ideas of how it might appear in the classroom. About the authors Carlos Islam teaches ESL and Applied Linguistics at the University of Maine. He is also involved in materials writing projects, editing Folio (the journal of the Materials Development Association www.matsda.org.uk ) and language acquisition research. Ivor Timmis is Lecturer in Language Teaching and Learning at Leeds Metropolitan University. He teaches on the MA in Materials Development for Language Teachers, works on materials development consultancies and is also involved in corpus linguistic research. References Batstone, Rob (1996). Key Concepts in ELT: Noticing. ELT Journal 50(3)273. Bolitho, R, Carter, R, Hughes, R, Ivanic, R, Masuhara, H, and Tomlinson, B (2003) Ten Questions about Language Awareness. ELT Journal 57/3. Lewis, Michael (1993), The Lexical Approach, Hove: Language Teaching Publications. Lewis, Michael (1997). Implementing the Lexical Approach: Putting Theory Into Practice. Hove: Language Teaching Publications. Lewis, Michael (2000). Language in the lexical approach. In Teaching Collocation: Further Developments In The Lexical Approach, Michael Lewis (ed.), 126-154.Hove: Language Teaching Publications. Schmitt, Norbert (2000). Key Concepts in ELT: Lexical Chunks. ELT Journal 54(4): 400-401. Thornbury, Scott (1997). Reformulation and reconstruction: tasks that promote 'noticing'. ELT Journal 51(4): 326-334. Carlos Islam, The University of Maine Ivor Timmis, Leeds Metropolitan University Teaching Vocabulary To Advanced Students: A Lexical Approach by Solange Moras, Sao Carlos, Brazil, July 2001 1. ADVANCED STUDENTS AND THEIR NEEDS Advanced learners can generally communicate well, having learnt all the basic structures of the language. However, they need to broaden their vocabulary to express themselves more clearly and appropriately in a wide range of situations. Students might even have a receptive knowledge of a wider range of vocabulary, which means they can recognise the item and recognise its meaning. Nevertheless, their productive use of a wide range of vocabulary is normally limited, and this is one of the areas that need greater attention. At this stage we are concerned not only with students understanding the meaning of words, but also being able to use them appropriately, taking into account factors such as oral / written use of the language; degree of formality, style and others, which we are going to detail in Part 2. 2. THE TEACHING OF VOCABULARY Traditionally, the teaching of vocabulary above elementary levels was mostly incidental, limited to presenting new items as they appeared in reading or sometimes listening texts. This indirect teaching of vocabulary assumes that vocabulary expansion will happen through the practice of other language skills, which has been proved not enough to ensure vocabulary expansion. Nowadays it is widely accepted that vocabulary teaching should be part of the syllabus, and taught in a well-planned and regular basis. Some authors, led by Lewis (1993) argue that vocabulary should be at the centre of language teaching, because ‘language consists of grammaticalised lexis, not lexicalised grammar’. We are going to discuss aspects of the ‘Lexical approach’ in Part 2. There are several aspects of lexis that need to be taken into account when teaching vocabulary. The list below is based on the work of Gairns and Redman (1986): · Boundaries between conceptual meaning: knowing not only what lexis refers to, but also where the boundaries are that separate it from words of related meaning (e.g. cup, mug, bowl). · Polysemy: distinguishing between the various meaning of a single word form with several but closely related meanings (head: of a person, of a pin, of an organisation). · Homonymy: distinguishing between the various meaning of a single word form which has several meanings which are NOT closely related ( e.g. a file: used to put papers in or a tool). · Homophyny:understanding words that have the same pronunciation but different spellings and meanings (e.g. flour, flower). · Synonymy: distinguishing between the different shades of meaning that synonymous words have (e.g. extend, increase, expand). · Affective meaning: distinguishing between the attitudinal and emotional factors (denotation and connotation), which depend on the speakers attitude or the situation. Socio-cultural associations of lexical items is another important factor. · Style, register, dialect: Being able to distinguish between different levels of formality, the effect of different contexts and topics, as well as differences in geographical variation. · Translation: awareness of certain differences and similarities between the native and the foreign language (e.g. false cognates). · Chunks of language: multi-word verbs, idioms, strong and weak collocations, lexical phrases. · Grammar of vocabulary: learning the rules that enable students to build up different forms of the word or even different words from that word (e.g. sleep, slept, sleeping; able, unable; disability). · Pronunciation: ability to recognise and reproduce items in speech. The implication of the aspects just mentioned in teaching is that the goals of vocabulary teaching must be more than simply covering a certain number of words on a word list. We must use teaching techniques that can help realise this global concept of what it means to know a lexical item. And we must also go beyond that, giving learner opportunities to use the items learnt and also helping them to use effective written storage systems. 2.1. MEMORY AND STORAGE SYSTEMS Understanding how our memory works might help us create more effective ways to teach vocabulary. Research in the area, cited by Gairns (1986) offers us some insights into this process. It seems that learning new items involve storing them first in our short-term memory, and afterwards in long-term memory. We do not control this process consciously but there seems to be some important clues to consider. First, retention in short-term memory is not effective if the number of chunks of information exceeds seven. Therefore, this suggests that in a given class we should not aim at teaching more than this number. However, our long-term memory can hold any amount of information. Research also suggests that our ‘mental lexicon’ is highly organised and efficient, and that semantic related items are stored together. Word frequency is another factor that affects storage, as the most frequently used items are easier to retrieve. We can use this information to attempt to facilitate the learning process, by grouping items of vocabulary in semantic fields, such as topics (e.g. types of fruit). Oxford (1990) suggests memory strategies to aid learning, and these can be divided into: · creating mental linkages: grouping, associating, placing new words into a context; · applying images and sounds: using imagery, semantic mapping, using keywords and representing sounds in memory; · reviewing well, in a structured way; · employing action: physical response or sensation, using mechanical techniques. The techniques just mentioned can be used to greater advantage if we can diagnose learning style preferences (visual, aural, kinesthetic, tactile) and make students aware of different memory strategies. Meaningful tasks however seem to offer the best answer to vocabulary learning, as they rely on students’ experiences and reality to facilitate learning. More meaningful tasks also require learners to analyse and process language more deeply, which should help them retain information in long-term memory. Forgetting seems to be an inevitable process, unless learners regularly use items they have learnt. Therefore, recycling is vital, and ideally it should happen one or two days after the initial input. After that, weekly or monthly tests can check on previously taught items. The way students store the items learned can also contribute to their success or failure in retrieving them when needed. Most learners simply list the items learnt in chronological order, indicating meaning with translation. This system is far from helpful, as items are decontextualised, encouraging students to over generalise usage of them. It does not allow for additions and refinements nor indicates pronunciation. Teachers can encourage learners to use other methods, using topics and categories to organise a notebook, binder or index cards. Meaning should be stored using English as much as possible, and also giving indication for pronunciation. Diagrams and word trees can also be used within this topic/categories organisation. The class as a whole can keep a vocabulary box with cards, which can be used for revision/recycling regularly. Organising this kind of storage system is time-consuming and might not appeal to every learner. Therefore adapting their chronological lists to include headings for topics and a more complete definition of meaning would already be a step forward. 2.2. DEALING WITH MEANING In my opinion the most important aspect of vocabulary teaching for advanced learners is to foster learner independence so that learners will be able to deal with new lexis and expand their vocabulary beyond the end of the course. Therefore guided discovery, contextual guesswork and using dictionaries should be the main ways to deal with discovering meaning. Guided discovery involve asking questions or offering examples that guide students to guess meanings correctly. In this way learners get involved in a process of semantic processing that helps learning and retention. Contextual guesswork means making use of the context in which the word appears to derive an idea of its meaning, or in some cases, guess from the word itself, as in words of Latin origin. Knowledge of word formation, e.g. prefixes and suffixes, can also help guide students to discover meaning. Teachers can help students with specific techniques and practice in contextual guesswork, for example, the understanding of discourse markers and identifying the function of the word in the sentence (e.g. verb, adjective, noun). The latter is also very useful when using dictionaries. Students should start using EFL dictionaries as early as possible, from Intermediate upwards. With adequate training, dictionaries are an invaluable tool for learners, giving them independence from the teacher. As well as understanding meaning, students are able to check pronunciation, the grammar of the word (e.g. verb patterns, verb forms, plurality, comparatives, etc.), different spelling (American versus British), style and register, as well as examples that illustrate usage. 2.3. USING LANGUAGE Another strategy for advanced learners is to turn their receptive vocabulary items into productive ones. In order to do that, we need to refine their understanding of the item, exploring boundaries between conceptual meaning, polysemy, synonymy, style, register, possible collocations, etc., so that students are able to use the item accurately. We must take into account that a lexical item is most likely to be learned when a learner feels a personal need to know it, or when there is a need to express something to accomplish the learner’s own purposes. Therefore, it means that the decision to incorporate a word in ones productive vocabulary is entirely personal and varies according to each student’s motivation and needs. Logically, production will depend on motivation, and this is what teachers should aim at promoting, based on their awareness of students needs and preferences. Task-based learning should help teachers to provide authentic, meaningful tasks in which students engage to achieve a concrete output, using appropriate language for the context. 2.4. THE LEXICAL APPROACH We could not talk about vocabulary teaching nowadays without mentioning Lewis (1993), whose controversial, thought-provoking ideas have been shaking the ELT world since its publication. We do not intend to offer a complete review of his work, but rather mention some of his contributions that in our opinion can be readily used in the classroom. His most important contribution was to highlight the importance of vocabulary as being basic to communication. We do agree that if learners do not recognise the meaning of keywords they will be unable to participate in the conversation, even if they know the morphology and syntax. On the other hand, we believe that grammar is equally important in teaching, and therefore in our opinion, it is not the case to substitute grammar teaching with vocabulary teaching, but that both should be present in teaching a foreign language. Lewis himself insists that his lexical approach is not simply a shift of emphasis from grammar to vocabulary teaching, as ‘language consists not of traditional grammar and vocabulary, but often of multi-word prefabricated chunks’(Lewis, 1997). Chunks include collocations, fixed and semi-fixed expressions and idioms, and according to him, occupy a crucial role in facilitating language production, being the key to fluency. An explanation for native speakers’ fluency is that vocabulary is not stored only as individual words, but also as parts of phrases and larger chunks, which can be retrieved from memory as a whole, reducing processing difficulties. On the other hand, learners who only learn individual words will need a lot more time and effort to express themselves. Consequently, it is essential to make students aware of chunks, giving them opportunities to identify, organise and record these. Identifying chunks is not always easy, and at least in the beginning, students need a lot of guidance. Hill (1999) explains that most learners with ‘good vocabularies’ have problems with fluency because their ‘collocational competence’ is very limited, and that, especially from Intermediate level, we should aim at increasing their collocational competence with the vocabulary they have already got. For Advance learners he also suggests building on what they already know, using better strategies and increasing the number of items they meet outside the classroom. The idea of what it is to ‘know’ a word is also enriched with the collocational component. According to Lewis (1993) ‘being able to use a word involves mastering its collocational range and restrictions on that range’. I can say that using all the opportunities to teach chunks rather than isolated words is a feasible idea that has been working well in my classes, and which is fortunately coming up in new coursebooks we are using. However, both teachers and learners need awareness raising activities to be able to identify multi-word chunks. Apart from identifying chunks, it is important to establish clear ways of organising and recording vocabulary. According to Lewis (1993), ‘language should be recorded together which characteristically occurs together’, which means not in a linear, alphabetical order, but in collocation tables, mind-maps, word trees, for example. He also suggests the recording of whole sentences, to help contextualization, and that storage of items is highly personal, depending on each student’s needs. We have already mentioned the use of dictionaries as a way to discover meaning and foster learner independence. Lewis extends the use of dictionaries to focus on word grammar and collocation range, although most dictionaries are rather limited in these. Lewis also defends the use of ‘real’ or ‘authentic’ material from the early stages of learning, because ‘acquisition is facilitated by material which is only partly understood’ (Lewis, 1993, p. 186). Although he does not supply evidence for this, I agree that students need to be given tasks they can accomplish without understanding everything from a given text, because this is what they will need as users of the language. He also suggests that it is better to work intensively with short extracts of authentic material, so they are not too daunting for students and can be explored for collocations. Finally, the Lexical Approach and Task-Based Learning have some common principles, which have been influencing foreign language teaching. Both approaches regard intensive, roughly-tuned input as essential for acquisition, and maintain that successful communication is more important than the production of accurate sentences. We certainly agree with these principles and have tried to use them in our class. 3. RATIONALE OF THE LESSON We believe that the Lexical Approach has much to offer in the area of vocabulary teaching, and therefore we have tried to plan a lesson that is based on its main concepts, specially exploring the use of collocations. 3.1 CHOICE OF MATERIAL As both the Task-based and the Lexical approach suggest, we wanted to use authentic material to expose our students to rich, contextualised, naturally-occurring language. For the topic of holidays we chose a big number of holiday brochures (about twenty five) and read them through, trying to notice recurrent patterns of lexis. Confirming what Hill (1999) affirmed, this analysis showed us a large number of collocations, specially adjective + noun ones, and that some were extremely common, such as golden sandy beaches, rolling countryside and others. We did not want to overload students with much reading, which would detract them from the main task of working with vocabulary, and therefore we selected twenty-one short yet meaningful extracts in which common collocations appeared. 3.2. NOTICING COLLOCATIONS AND DEALING WITH MEANING Although the extracts are authentic, we do not think students will have many problems in understanding most of the collocations, as they contain vocabulary which they probably know receptively. This again should confirm the idea that students know individual words but lack collocational competence. We are going to work as a whole class in step 5 to make students aware of the collocations we will be focusing on, and hopefully this will enable students to find other collocations. Regular awareness raising activities like this should help students improve their collocational competence, and even fluency, as discussed in part 2.4. For the few words that we predict students will not fully understand meaning of, or are not sure how they are pronounced, we are going to ask them to look these up in monolingual dictionaries. As we said in part 2.2., dictionaries are a vital tool for Advanced learners, and so is contextual guesswork, which we are going to encourage before they look the words up. We are also going to ask students to notice examples given in the dictionary, observing and recording other possible collocations of the words, as suggested by Lewis. We have also taken into account the importance of recording the vocabulary observed during the class. The list that students will produce in step 9, to prepare for the final task, is also a way of recording vocabulary in an organised, personalised and meaningful way, as suggested by Lewis in part 2.4. 3.3. GROUP WORK Working in groups help fostering learning independence, and specially in vocabulary work, learners can exchange knowledge, asking others to explain unknown items. We also hope that group work will be a motivating factor, as students talk about places they have been on holiday to, trying to remember details together, exchanging impressions and even good memories! 3.4. CHOICE OF TASK As we said earlier in part 2.3, we find it vital that students are given opportunities to use the language they are learning in a realistic context. Therefore, we have devised the final task to meet this principle. Writing a leaflet is a possible task in the Cambridge Certificate of Advanced English, which these students are preparing for. It is also a relevant, real life task that we expect will interest students. I always like to mention that the standard of leaflets written in English in Brazil is very poor, and that they could do a much better job. We expect that this writing should also enable students to use the vocabulary they have studied in a realistic context, and that they could be motivated to learn even more vocabulary they feel they need to accomplish the task. The completion of the final task for homework will also help to reinforce and revise the vocabulary learnt, giving students a better chance to store the items in their long-term memory, as we mentioned in part 2.1. We are going to explain what the final task will be right after step 3, in which they should notice what kind of text the extracts come from. By doing this we want to motivate students to do the enabling tasks, mainly to show them the need to learn new vocabulary. As this is a borrowed group, it might be the case the students are not yet familiar with the leaflet format, in which case more input would be necessary before the conclusion of the final task. If students are really interested in the task, this could be transformed into a project, involving research and the production of a leaflet or web page in the multi-media centre. References Allen, V. (1983) Techniques in teaching vocabulary. OUP. Gairns, R. Redman, S.(1986) Working with words. CUP. Hill, J. (1999) ‘Collocational competence’ English Teaching Professional, 11, pp. 3-6. Lewis, M. (1993) The lexical approach. LTP. Lewis, M. (1997) Implementing the lexical approach. LTP Oxford, R.(1990) Language learning strategies. Newbury House. Richards, J. (1985) The context of language teaching. CUP. Scrivener, J. (1994) Learning teaching. Heinemann. Thornbury, S. (1998) ‘The lexical approach: a journey without maps’. MET, 7 (4), pp. 7-13 Willis, J. (1996) A framework for task-based learning. Longman. The lexical approach revisited Posted on September 30, 2008 by Ken Carroll Below is a passage taken from an old ChinesePod blog post about the lexical approach. It is a subject I hope to revist as I think it has certain connectivist implications, so here it is: “Beginning in the 1980s, computer-based studies (mainly of English) began to provide us with powerful insights into the workings of our language. Linguists fed millions of English documents into software programs to scan them and see what they might yield about their patterns of behavior. These studies were known as ‘corpora’ studies. From the beginning, the corpora studies began to reveal surprising insights into how words interact and behave with other. The studies offered empirical data, based on a very broad range of English language sources. They allowed us to take a given word or expression and look at how it behaved over the course of thousands of examples – how it was used grammatically, where it was likely to be used, with whom it as most likely to keep company, etc. The results were often startling and they began to challenge traditional ideas about the role of grammar and even about how we defined grammar. One outgrowth of these studies was the development of the ‘lexical approach’ to language teaching. The first description of a lexical approach is attributed to Michael Lewis, who wrote a book of that title in 1993. This book became a classic amongst language teachers and I myself have been greatly influenced by it over the years. I convinced that the lexical approach (with some revisions) offers very useful insights into how we might approach the study of Mandarin, so let me explain a little about what it is. The most striking revelation from the corpora concerns how words tend to associate strongly with other words in the form of chunks, fixed expressions, collocations, etc. As an example, let’s take a look at collocation. The word ‘collocation’ refers to the tendency amongst words to collocate, or ‘co-locate’ (appear close to) certain other words. Some random examples (out of millions of possibilities): seriously ill serious problem serious accusation common cold unfair advantage decisive action strong tea join hands commit a crime If you typed the word ’seriously’, into the corpora software, it would yield thousands of sentences (taken from original documents) and show you the words that ’seriously’ was most likely to appear next to. In this case, ’seriously’ occurred much more frequently with the word ‘ill’ than with any other word. We can therefore say that ’seriously’ collocates with ‘ill’. The word ’serious’, meanwhile, is more likely to appear next to ‘problem’ or ‘accusation’ than with any other words, and so on. The other phrases on the list above are every day expressions (or collocations) that every native speaker of English knows. But here’s the really interesting thing: even advanced level non-native speakers are unlikely to know these expressions! In fact a non-native speaker is more likely to make a mistake when using such expressions than to use bad grammar. (If ever you are in doubt about whether someone is a native speaker of English, just test his/her knowledge of these kinds of expressions.) To non-language teachers, the examples of collocations I offer may seem trite, but let me tell you that they set off a firestorm of innovation and debate in the language teaching world that has continued unabated to this day. (Actually, while we’re at it, ‘to this day’ is a nice fixed expression, while the word ‘unabated’ tends to occur with ‘floods’ or ‘firestorms’ or things like that, for some reason!)” How You Can Use the Lexical Approach to Study English The lexical approach is not new anymore. Yet some people have not heard of it. My studies tell me that it is more effective than studying grammar. I have not given up teaching grammar, but I teach it as a support to lexical studies. "So what is it?" you might be asking. Well, it is a way of learning language through words and groups of words. The groups are: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. words (e.g., book, pen) phrases (sometimes called polywords ; examples are by the way, inside out) collocations (words that frequently go together and sound natural) groups of words with a basic meaning (I'll think about it, Would you like...?, If I were you...) sentence starters ( What I mean is..., The fact was...) Now we get to the guts of this article: how can you use this approach? The first thing is to do a lot of intensive and extensive listening and reading in English. Your reading should support the primary skill: listening. (You can practice intensive listening below with the phrasal verb story in the video. ) Compare English to your language in a chunk-by-chunk basis rather than word-by-word (which only tends to confuse students). This is why the grammar translation method is unworkable (are you still using the grammar translation method?) In the lexical approach, you should repeat activities, and review lots, so previous learned material is not forgotten. I repeat the same story for listening practice two or even three weeks in a row with my students. I recommend listening to a story on this site three or four times in a week. Then start a new story, and listen to the old one again a week or two later. Guess the meaning of new vocabulary from context. This is a strong vocabulary builder and skill builder. Only look up a word in a dictionary after the third or fourth time you hear (read) it. Notice and record the larger language chunks, and memorize them. Make a lexical approach notebook for this. Read it once a day. Have fun working with the lexical approach. Rusty Swimmers Phrasal Verb List 1. Come along to go somewhere with someone 2. Let off to not punish someone who has committed a crime or done something wrong; or not to punish severely 3. Mess with to become involved with someone or something that's dangerous 4. Patch up to try and improve your relationship with someone after an argument. 5. Rust away to be gradually destroyed by rust Micheal cannot see. He loves swimming, and wants to go every week. His friend Larry always asks him to come along to the pool and they swim together. Once Larry did not ask Micheal, and the next day Micheal was very angry. Larry went to visit Micheal and Micheal tried to hit him. Larry told Micheal not to mess with him, becuase he had studied Karate. Micheal just said 'Ha!, You haven't practiced in years! Your skills are just rusting away!' Larry just shrugged and left. They both felt bad about what they did. A few days later, they patched things up. Larry thinks Micheal let him off, and Micheal thinks Larry let him off. Now they swill together without fail. http://www.english-listening-world.com/lexical-approach.html