Translation Universals

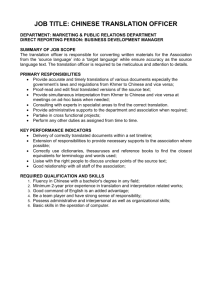

advertisement