apoesn22

advertisement

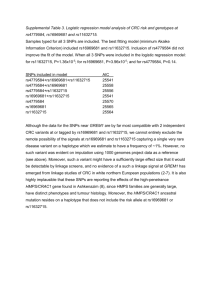

Further investigation of linkage disequilibrium between SNPs and their ability to identify associated susceptibility loci Summary There is currently considerable interest in the use of single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) to map disease susceptibility genes. The success of this method will depend on a number of factors including the strength of linkage disequilibrium (LD) between marker and disease loci. We used a data set of SNP genotypings in the region of the APOE disease susceptibility locus to investigate the likely usefulness of SNPs in casecontrol studies. Using the estimated haplotype structure surrounding and including the APOE locus and assuming a codominant disease model we treated each SNP in turn as if it were a disease susceptibility locus and obtained, for each disease locus and markers, the expected likelihood ratio test (LRT) to assess disease association.We were particularly interested in the power to detect association with the susceptibility polymorphism itself, the power of nearby markers to detect association, and the ability to distinguish between the susceptibility polymorphism and marker loci also showing association. We found that the expected LRT depended critically on disease allele frequencies. For disease loci with a reasonably common allele we were usually able to detect association. However for only a subset of markers in the close neighbourhood of the disease locus was association detectable. In these cases we were usually, but not always, able to distinguish the disease locus from nearby associated marker loci. For some disease loci no other loci demonstrated detectable association with the disease phenotype. We conclude that one may need to use very dense SNP maps in order to avoid overlooking polymorphisms affecting susceptibility to a common phenotype. Keywords: linkage disequilibrium, disease locus mapping, ApoE Introduction The ability to fine-map disease susceptibility genes using closely spaced markers depends on the LD relationships between the polymorphisms involved and on the nature of the effect of the disease polymorphism on susceptibility. The process is complicated by the fact that the relationship between physical distance and LD is not monotonic but is affected by historical events such as genetic drift, admixture, multiple mutations and natural selection (Nordborg and Tavare, 2002) and by variations in recombination rates between regions leading to phenomena such as the observation of haplotype blocks (Cardon and Abecasis 2003). The ability to detect association of a marker with disease will also depend on the marker’s allele frequencies. We have shown (Sham et al. 2000) that for relatively rare mutations the ability to detect association with disease increases as the number of alleles of a marker rises to around 5 or 10, and that this effect is especially strong when more than one pathogenic mutation event has occured in the gene during evolution. However Correspondence: Dr David Curtis, Department of Adult Psychiatry, 3rd Floor, Outpatient Building, Royal London Hospital, London E1 1BB. E-mail: dcurtis@hgmp.mrc.ac.uk different considerations might apply for common polymorphisms which could occur on the background of several different haplotypes. Finally, for a given pattern of LD it will be easier to detect a susceptibility polymorphism which has a major rather than a minor effect on risk of affection. To explore these issues, a previous study investigated 60 SNPs in the region surrounding the APOE locus in a sample of cases suffering from Alzheimer’s disease and controls (Martin et al, 2000). The APOE locus provides a good example of a polymorphism affecting susceptibility to a common disease with a complex mode of inheritance. Studying the surrounding SNPs allowed insights to be gained regarding the ability of to fine-map similar loci with similar effects, assuming that similar patterns of LD might be present elsewhere in the genome. SNPs were analysed in a region ~1.5 cM distal of APOE and ~190 kb proximal. 16 of the 60 SNPs showed evidence for association with disease at p<0.05 using either allelic or genotypic tests for association, and of these 7 lay within 40 kb of APOE. Of these 7, 4 yielded a significance at p<0.05 when corrected for the number of markers analysed. The APOE-4 polymorphism itself produced highly significant evidence for association, as did 2 other SNPs nearby. The evidence for association with APOE-4 was nevertheless appreciably stronger than for these other two loci. The authors concluded that a high density of SNPs would be necessary to in order to have a good chance of including SNPs with detectable levels of allelic association with a disease mutation. A recent study of markers around the DBH locus has produced results which are in some ways similar (Zabetian et al 2003). This found that only markers within a 10 kb haplotype block were strongly associated with the phenotype influenced by a DBH polymorphism, and the authors concluded that if by chance these markers had not been included in an association study then the role of the DBH locus could have been overlooked. In the current study we sought to gain a further assessment of the likely usefulness of SNPs in case-control studies by using the APOE dataset but treating each SNP in turn as if it were a disease susceptibility locus. While the previous study included 59 marker SNPs along with the susceptibility polymorphism itself, this would allow us to investigate thousands of pairs of marker-disease loci (the pairs admittedly being nonindependent). To do this, we used the observed patterns of LD in the dataset and calculated the allele frequencies we would expect to observe at each SNP given a specified disease model and contingent on these LD relationships. We sought in particular to address three issues regarding the power of association studies, namely: the expected observed association with the susceptibility polymorphism itself; the ability of nearby markers to detect association; the ability to distinguish between the susceptibility polymorphism and marker loci also showing association. Method As previously described (Martin et al, 2000) the data consisted of consisted of 220 unrelated cases of late onset Alzheimer’s disease and 220 controls collected by the Bryan Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center at Duke’s University Medical Centre, all subjects being white. 60 SNPs in the region surrounding APOE, including APOE-4 itself, were genotyped, new SNPs being generated by screening seven controls using YAC truncation and random sequencing (Lai et al, 1998). For the current study one of Investigation of linkage disequilibrium the SNPs, SNP474, which lies a long way distant from the others was discarded. For the remaining 59 SNPs, the allele frequencies from the combined dataset of cases and controls were calculated and two-locus haplotype frequencies were estimated using the EH+ program (Zhao et al, 2000). This estimation by the EH+ program assumes Hardy-Weinburg equilibrium although in the APOE data this assumption was not the case for a small number of locus. These frequency estimates were then used as if they represented population allele and haplotype frequencies. It should be noted that because the case and control samples were of equal size this would lead to an overestimate of the frequency of the APOE-4 allele and other alleles in LD with it which are also associated with Alzheimer’s disease. Likewise, the magnitude of LD occurring with associated markers might be somewhat different from that which would be observed in an unselected sample. We do not believe that this poses a problem for the current study, since we wished merely to obtain some representative estimates for allele frequencies of SNPs generally and for typical patterns of LD between pairs of SNPs near to each other. The observed allele frequencies were used to calculated the D’ measure of LD (Lewontin 1964) and this was plotted against the distance between loci in each pair. We used the observed allele frequencies and estimated haplotype frequencies to calculate the allele frequencies we would expect to observe for all SNPs if we obtained a sample of cases and controls, contingent on each SNP in turn being a susceptibility polymorphism for disease. Thus, for each SNP we calculated the expected numbers of cases and controls having each genotype if that SNP itself influenced susceptibility to disease. Next, using the estimated haplotype frequencies we calculated the expected genotypes of every other SNP in cases and controls given the expected genotypes of the disease SNP. We could then calculate what evidence we would obtain for association if the disease SNP itself or any of the 58 other SNPs were analysed. Repeating this process for each SNP would yield 59 studies of association with a disease locus and 3,422 studies of a marker lying close to a disease locus. To model the effects of the susceptibility locus, we assigned penetrance values previously estimated in a Finnish population estimated by Kuusisto et al (1994) to be the probabilities of affection with Alzheimer’s disease conditional on possessing 0, 1 or 2 copies of the APOE-4 allele. These values consisted of 0.029, 0.076 and 0.214. They were used for every SNP, regardless of its allele frequency. What this means is that we were assuming that the polymorphism would have a constant biological effect in terms of its effect on absolute risk of the disease. However using various allele frequencies would mean that the diseases being modelled had different prevalences in the population and also that the risk fraction attributable to the locus under consideration would vary. We took these penetrance values as an example of a susceptibility locus having a known effect size. Of course, the power studies we performed would be critically dependent on the disease model and our results can thus only be taken to provide some illustration of the kinds of effects which might be seen in practice. Taking each SNP as the disease locus and having observed allele frequencies p1 and p2, we calculated the expected frequency for each genotype would as follows. For affected cases: mA11=f11p12/K, mA12=2f12p1p2/K and mA22=f22p22/K For unaffected controls: mU11=(1-f11)p12/(1-K), mU12=2(1-f12)p1p2/(1-K) and mU22=(1f22)p22/K Where the population prevalence of the disease is K= f11p12+2f12p1p2+f22p22 and the penetrances have the previously stated values f11=0.029, f12=0.076 and f22=0.214. To calculate the frequency of marker genotypes for the other SNPs we used the estimated haplotype frequencies, using hjk to denote the frequency of the haplotype having allele j at the disease locus and allele k at the marker locus. Expected frequencies for homozygotes and heterozygotes were estimated according to the formulae given in Sham (1997). In cases: mAjj =( f11 h1j 2 + 2 f12 h1j h2j + f22h2j2)/K and: mAjk =( f11 h1j h1k + 2 f12 (h2j h1k + h1j h2k )+ f22 h2j h2k)/K In controls: mUjj =( (1-f11) h1j 2 + 2 (1-f12 )h1j h2j + (1-f22)h2j2)/(1-K) and: mUjk =((1-f11) h1j h1k + 2 (1-f12)(h2j h1k + h1j h2k )+ (1-f22)h2j h2k)/(1-K) We used these genotype frequencies to calculate expected allele counts in samples of N0 controls and N1 cases, so that for each allele n0j=(2mUjj+mUij) and n1j=(2mAjj+mAij). In order to determine the strength of evidence for association that might be observed in a case-control study we then calculated the value for a likelihood ratio test (LRT) statistic based on these expected counts: G2 = 2 ∑ nij ln (nij/νij) where the expected counts assuming no association are given by νij=Ni(n0j+n1j)/(N0+N1). This LRT statistic is asymptotically distributed as chi-squared with one degree of freedom. It has the advantage over the commonly used Pearson’s chi-squared test that it scales linearly with sample size so that once one knows the value of the statistic one can expect from a given sample one can readily calculate the sample size which would be expected to produce any given value of the test statistic. We denote the statistic obtained for the disease polymorphism itself as G2D and for each marker SNP as G2M. For every pair of SNPs we calculated and plotted the LD measure D’ against distance between them. We also calculated the LRT statistic indicating the statistical significance of deviance from the haplotype frequencies expected assuming no LD, using the full sample of 440 case and control subjects. We then assumed the same sample size of 440 to calculate the statistics we would expect to obtain using the procedures above, taking each SNP in turn as if it affected disease susceptibility. For each SNP we calculated and plotted the value of G2D, indicating the evidence for association with the disease locus itself, and then it was paired with each other SNP in turn, with the other SNP being treated as a marker, and we calculated the value for G2M, indicating the evidence for association of the marker SNP. For each of these Investigation of linkage disequilibrium pairs of SNPs we then plotted the value of G2M against the distance between the marker and the disease locus. When carrying out a case-control association study, association may be observed both with the disease polymorphism itself and with markers in linkage disequilibrium with it. If the observed association is much stronger with the disease polymorphism then one may use this observation to distinguish which one of the associated polymorphisms directly affects susceptibility and which ones are markers showing secondary association due to LD. However if the LD is very strong then a marker may be as strongly associated as the disease polymorphism and it may be difficult to distinguish which is which on genetic grounds. If all the SNPs in a particular region were typed then a number might show association with disease status. In order to investigate the power of a case-control sample to distinguish disease from marker polymorphisms, for each SNP treated as a disease polymorphism we compared the value of G2D against the maximum value for G2M obtained for any of the other SNPs. The difference between these values, G2D-max(G2M), provides a measure of the strength of evidence for the disease polymorphism rather than the most strongly associated marker polymorphism to be the one which directly influences susceptibility to disease. For example, since the statistics are based on 2ln(L), if the value of G2Dmax(G2M) exceeds 2ln(100)=9.2 then the likelihood ratio in favour of the disease polymorphism rather than the marker polymorphism affecting susceptibility would be greater than 100. To assess the ability of marker polymorphisms to detect association and the ability to distinguish a disease polymorphism from marker polymorphisms we plotted max(G2M) for each disease SNP against G2D. Results Figure 1 shows the value of D’ plotted against inter-SNP distance for every pair of SNPs. It can be seen that high values of D’ can be found even between SNPs which are separated by distances of over 1,000 kb. It does not appear that D’ declines particularly rapidly with distance and within 1000 kb there is only a fairly weak negative correlation of r=−0.20 between D’ and distance. However Figure 2 throws a somewhat different light on this finding. This shows that the statistical significance of the LD which we might expect to observe with a sample size of 440, as measured by the LRT statistic distributed as χ21, in fact falls off very rapidly with distance. Several extremely high LRT statistics are obtained between SNPs within 150 kb of each other and most of the statistically significant statistics occur within this range, although a few highly significant statistics occur at distances up to 300kb. The explanation for the discrepancy between the distances over which high values of D’ are found and over which these values are statistically significant is that the high D’ values at large distances tend to be produced by SNPs having low allele frequencies. These can lead to the absence or near-absence of one haplotype, producing a high D’ but one which is not statistically significant (Zapata et al 2001). This is an important point and shows that relying on D’ as a measure of LD may not tell us much about what we might call useful LD, that is the kind of LD which can detect statistically significant association between loci. Figure 3 shows the values for G2D, the LRT statistic produced by the susceptibility polymorphism itself showing association with disease status, which we might expect to observe with a sample size of 440. These values are entirely dependent on the allele frequencies of the SNP in question, and show that for this sample size many susceptibility loci having the kind of effect modelled can be expected to produce statistically significant evidence for association with disease, which will be strongest when the alleles have similar frequencies. This is the case when the rarer allele still has a frequency of more than 0.15-0.2. However as this frequency becomes lower then the expected value for G2D falls rapidly and it can seen that several SNPs would produce values which would be regarded as only of borderline significance or not significant at all. It should be remembered that the expected value of G2D is directly proportional to the sample size so used, so another way of putting this observation would be to say that larger sample sizes would be required to detect the effect of those SNPs in which one allele was relatively rare. Figure 4 shows the values for G2M which we might expect to obtain when we study a marker SNP rather than the susceptibility polymorphism itself. Again, what we see is that association with disease which is statistically significant at p<0.05 is only observed at distances less than 300 kb and that only markers less than 100 kb from the disease locus produce strong evidence for association. Within 100 kb, the correlation between G2M and distance is low, with r=−0.16. Even within this distance, many disease-marker pairs fail to show any detectable evidence for association and out of 530 pairs which are not more than 100 kb apart only 77 produce a result significant at p<0.05 and only 52 are significant at p<0.01. If attention is restricted to diseasemarker pairs within 10 kb of each other then the proportion of significant results increases. However out of 88 such pairs there still only 33 which were significant at p<0.05 and 25 which were significant at p<0.01. Figure 5 shows the value for max(G2M) plotted against G2D. This demonstrates the ability to detect association using a marker SNP rather than the disease polymorphism itself, and also enables one to assess the extent to which the effect of a disease polymorphism could be distinguished from a marker polymorphism in LD with it. One thing which is apparent is that for a number of disease polymorphisms there is no other SNP which gives notable evidence for association with the disease phenotype. Of the 59 SNPs treated as a disease polymorphism, 51 are expected to produce a value of G2D significant at p<0.01. However only 28 have max(G2M) significant at p<0.01 and only 33 have max(G2M) significant at p<0.05. Thus for about a third of disease polymorphisms which themselves produce evidence for association one would fail to detect any association unless this polymorphism itself were studied. Even if all the surrounding SNPs were genotyped one still would not find any evidence implicating the region. The figure shows that this can happen even with polymorphisms which themselves produce very strong evidence for association with values of G2D exceeding 25. For the majority of polymorphisms max(G2M) is statistically significant but is considerably lower than G2D. This means that one could detect association through genotyping marker SNPs but when the disease polymorphism was genotyped it would be distinguished by being more strongly associated with the disease phenotype and so there would be good genetic evidence to favour it over other polymorphisms. However there are a few disease loci for which G2D is very high, ranging from 20 to 30, but which have a value for max(G2M) which is not much lower. For these cases, it would be hard to distinguish between the effects of the disease and marker polymorphisms. This arises because of very strong LD between some pairs of SNPs. Investigation of linkage disequilibrium On detailed examination of the data it could be seen that SNPs SNP509, SNP506, SNP507 and SNP502, which are physically very close to each other, were in strong LD, making their individual effects difficult to distinguish. Discussion Although our results pertain only to one particular model for the effect of a polymorphism on risk of affection, they do provide some insights into the kinds of effects we may expect to see when carrying out case-control studies of complex diseases. We should begin by emphasising that we have considered only a very simple model, with there being only one polymorphism influencing susceptibility. In a real situation, it would be quite possible that different polymorphisms could occur within the same gene, each having a different effect on susceptibility. Discriminating the effects of two or more such polymorphisms would represent a far more complex task than the simple detection of association. Also, we have ignored haplotype relationships between markers (rather than between marker and disease loci). Making use of marker haplotypes would introduce many additional complexities. It is possible that making use of haplotypes could at least in some circumstances enhance the ability to detect association, as has previously been demonstrated when studying markers around APOE in a family sample (Martin et al, 2000). Treating two or markers as providing haplotypes can allow the creation of multiallelic multilocus genotypes which can be more informative than biallelic markers (Sham et al 2000). If haplotype blocks can be reliably and replicably identified then they may also be treated as multallelic markers and redundancies in genotyping may be avoided (Daly et al, 2001). However it is by no means straightforward to derive haplotypes and the applicability of such approaches remains to be fully explored. Another issue to be borne in mind is that our results are based entirely on expected genotype and haplotype frequencies. In real samples chance factors can result in marked deviations from the expected frequencies of observed genotypes. Such random effects might act to strengthen or weaken the overall evidence for association or even, for example, to produce datasets in which a marker showed stronger association with the affection phenotype than did the susceptibility polymorphism itself. Finally, we would add that the results we have obtained relate only to the genetic region and sample subjects which we have studied. For example, the study of markers around DBH seemed to show LD extending over shorter distances than we detected around APOE (Zabetian et al 2003). Even from the simple studies which we have done we feel it is possible to derive a few useful conclusions. Firstly, it does seem that at least in some circumstances casecontrol studies should have reasonable power to detect association using realistic sample sizes, provided that the disease polymorphism itself is genotyped. However the power to detect association is sensitive to the allele frequencies. Where one allele is rare the polymorphism will make only a small contribution to the overall risk of affection in the population, even when the absolute effect on risk remains constant. In such a case far larger samples would be required to detect association. In the current study only a few SNPs had an allele so rare as to make the detection of association problematic, although of course to some extent the method used for detecting SNPs will have meant that there are rarer ones present in the region which have not been discovered. It is very simple to calculate the expected power to detect association given any particular disease model incorporating effect of genotype on risk and allele frequencies. However for non-Mendelian diseases these parameters are not known in advance. Even if one can use linkage information to estimate the overall effect on risk due to a particular region, one has no idea how many different susceptibility polymorphisms may be present in that region. Hence one may be able to put an upper limit on the power of a study but the actual power may be much lower than this if the effect is due to the action of several rare polymorphisms at the same locus. The second main finding is that, broadly speaking, detecting association using markers in the region of a disease polymorphism is far more problematic than using the disease polymorphism itself. Association is unlikely to be detected unless the marker is very close to the disease polymorphism. This finding holds in spite of the fact that D’ can be close to 1 even between pairs of SNPs at distances of 1,000 kb or more from each other, and in fact it could be argued that D’ is a somewhat misleading measure of LD in this situation. Even within 300 kb many markers will show no appreciable evidence for association with disease and for the vast majority the evidence will certainly be much weaker than for the disease polymorphism itself. For about half of the SNPs we studied, there was no other marker which would have produced notable evidence for association if that SNP had been a disease polymorphism. It seems difficult to avoid the conclusion that when searching for a disease polymorphism one should make efforts to identify and study every SNP within a region. If one fails to do this but instead only studies only a sub-sample one runs a substantial risk of failing to detect association and falsely concluding that the region does not harbour a susceptibility polymorphism. It could be argued that using haplotype information would mitigate against this problem and we have not been able to assess the extent to which this would be the case in this dataset. However it seems doubtful that haplotypes could be guaranteed to provide strong evidence for association when no marker individually was even weakly positive. This may be especially the case for common polymorphisms rather than rare disease mutations. One might hope that a rare disease mutation would occur on the background of only one or two haplotypes, but a common polymorphism having a more modest effect on susceptibility might well be shared between several haplotypes, reducing the gain in information which examining haplotypes might otherwise provide. By contrast, there were a small number of SNPs which were in very strong LD with each other, to the extent that it would have been problematic to determine which one directly influenced susceptibility and which ones were acting as markers. The LD was so strong that very large samples would be required to provide statistical evidence based on differences in strength of association. If confronted with this situation one might need either to obtain samples from other populations in which LD between the pairs of SNPs happened to be lower or else to carry out functional studies in order to decide which SNP was more likely to be having a direct effect on susceptibility. Our results are in line with previous studies which indicate that detecting polymorphisms influencing complex disease is at best a risky affair. Even if a susceptibility polymorphism is itself genotyped the statistical signficance of the difference in allele frequencies between cases and controls is critically dependent not only on the biological effect of the polymorphism but also on the frequencies of its alleles. If nearby marker SNPs are genotyped then they may provide evidence for association, but equally there is a strong possibility that none will do so, even if they are very close to the susceptibility polymorphism. This finding would lead to the Investigation of linkage disequilibrium conclusion that extremely dense SNP maps would be needed to avoid missing important loci. The extent to which the use of haplotype blocks will mitigate this problem remains to be seen – certainly we seem to see many SNPs which do not appear to be in LD with any of those nearby. Additional investigations into the LD relationships between different polymorphisms in different parts of the genome and the extent to which the use of haplotypes can enhance the ability to detect association with a disease phenotype should be carried out to elucidate these issues further. References Daly, M.J., Rioux, J.D., Schaffner, S.F., Hudson, T.J., Lander, E.S. (2001) Highresolution haplotype structure in the human genome. Nat. Genet. 29, 229–232. Kuusisto, J., Koivisto, K., Kervinen, K., Mykkanen, L., Helkala, E.L., Vanhanen, M., Hanninen, T., Pyorala, K., Kesaniemi, Y.A., Riekkinen, P., et al. (1994). Association of apolipoprotein E phenotypes with late onset Alzheimer's disease: population based study. British Medical Journal 309, 636-8. Lai, E., Riley, J., Purvis, I., & Roses, A. (1998) A 4-Mb high-density single nucleotide polymorphism-based map around human APOE . Genome Res. 54, 31-38. Lewontin, R.C. (1964) The interaction of selection and linkage. I. General considerations; heterotic models. Genetics 49, 49-67. Martin, E.R., Lai, E.H., Gilbert, J.R., Rogala, A.R., Afshari, A.J., Riley, J, Finch, K.L., Stevens, J.F., Livak, K.J., Slotterbeck, B.D., Slifer, S.H., Warren, L.L., Conneally, P.M., Schmechel, D.E., Purvis, I., Pericak-Vance, M.A., Roses, A.D., Vance, J.M. (2000). SNPing away at complex diseases: analysis of single-nucleotide polymorphisms around APOE in Alzheimer disease. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 67, 383-94. Nordborg, M. & Tavare, S. (2002). Linkage disequilibrium: what history has to tell us. Trends in Genetics 18, 83-90. Sham, P.C. (1998) Statistics in Human Genetics. Arnold Sham P.C., Zhao J.H., & Curtis, D. (2000) The effect of marker characteristics on the power to detect linkage disequilibrium due to single or multiple ancestral mutations. Ann. Hum. Genet. 64, 161-169. Zapata C, Carollo C & Rodriguez, C (2001) Sampling variance and distribution of the D' measure of overall gametic disequilibrium between multiallelic loci. Ann. Hum. Genet. 65, 395-406. Zabetian CP, Buxbaum SG, Elston RC, Kohnke MD, Anderson GM, Joel Gelernter J, Cubells JF (2003) The structure of linkage disequilibrium at the DBH locus strongly influences the magnitude of association between diallelic markers and plasma dopamine beta-hydroxylase activity. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 72, 1389–1400. Zhao J.H., Curtis D & Sham P.C. (2000) Model-free and permutation analysis for allelic associations. Hum. Hered. 50, 133-139. Investigation of linkage disequilibrium 1 D' 0.8 0.6 0.4 0.2 0 0 500 1000 1500 2000 Distance (kb) Fig. 1. Graph showing extent of LD between pairs of markers as measured by D’ against inter-marker distance LD LRT statistic 800 600 400 200 0 0 500 1000 1500 2000 Distance (kb) Fig. 2. . Graph showing extent of LD between pairs of markers as measured by EH+ LRT statistic against inter-marker distance Disease LRT statistic Investigation of linkage disequilibrium 35 30 25 20 15 10 5 0 0 0.2 0.4 0.6 0.8 1 Risk allele frequency Fig. 3. Effect of risk allele frequency on disease locus LRT statistic, G 2 D, for each of the 59 SNPs treated as a disease locus Marker LRT statistic 35 30 25 20 15 10 5 0 0 500 1000 1500 2000 Distance (kb) Fig. 4. Graph of marker LRT statistic, G2 M, against distance between disease locus and marker locus for all 59x58 disease locus-marker combinations Investigation of linkage disequilibrium Maximum marker LRT statistic 40 30 20 10 0 0 10 20 30 40 Disease LRT statistic Fig. 5. Graph of the maximum value of all marker LRT statistics, G 2 M, against the disease locus LRT statistic, G2 D