Advanced/Gifted English 9 & World History

advertisement

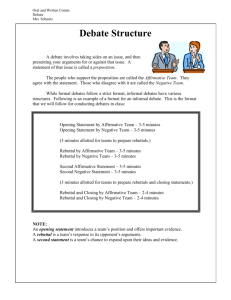

Advanced English 9 & World History Mrs. Eiserman & Mr. Mandel Name: ______________________ Third Quarter DEBATING REVOLUTION As the ideas of the Enlightenment philosophers percolated throughout Europe and over into North America in the 1700s, groups of individuals decided to turn ideas on personal liberty and representative government into action. Colonists in North America took the first step toward revolution when they protested the mercantilist policies of the British crown in the 1760s and early 1770s. Disagreement over the issue of taxation without representation led to an armed struggle for independence that began with “the shot heard ‘round the world” at Lexington and Concord in April 1775 and ended with the “world turned upside down” at the Battle of Yorktown in October 1781. The American independence movement set a momentous precedent for the use of violent force to overthrow an unrepresentative government. Within a decade, the French revolution proved that Europe was not immune to revolutionary ideas. The chaos and bloodshed experienced by France from the storming of the Bastille in 1789 until the “election” of Napoleon Bonaparte as First Consul in 1799 raised the question of whether revolutionary ideas could be carried too far. Objective This interdisciplinary lesson will consist of a formal debate on the following resolution. RESOLVED: The use of violent force to overthrow an unrepresentative government is justified. The graded elements of the debate will include preparation, participation, and a written commentary, as described in further detail below. Format The debate format pits one half of your block against the other. One class section will be assigned to the affirmative (yes, violent force is justified; viva la revolution!) and the other to the negative (no, you uncivilized brutes, it is not justified). To add historical flavor, the debate will be set in the British Parliament in the year 1800. (No, you do not have to speak with an accent. Yes, you may, if you wish). In reality, Ministe rs of Parliament often heatedly debated issues related to the American and French Revolutions. The debate over whether or not revolution was justified usually split down party lines between conservative Tories (who thought revolution was dangerous) and liberal Whigs (who often supported the revolutionaries in spirit, even when Britain went to war against “the colonies” and France). Nevertheless, we will need to take some liberties with history because, by 1800, most British MPs were in agreement that revolutionary France posed a threat to British national interests, especially after Napoleon’s invasion of Egypt in 1798. Setting the debate in 1800 provides the advantage of being able to draw upon the history of the French Revolution, including its great achie vements and excesses, to support and attack the arguments on both sides. The debate format will be an abbreviated version of that used in debate competition. Four students from each class section will be assigned to share out the formal speaking and questioning roles. Everyone else will be assigned specific research and support roles. Your goal is to work as a team to ensure that your case stands up under the scrutiny of the opposition, as well as your teachers. The formal debate will be held on Tuesday, February 1 and will last approximately sixty minutes. We will reserve thirty minutes for an open parliamentary style question and answer period, in which members of each side can freely challenge other members and make brief statements of their own. The formal debate segment will be run as follows: First Affirmative Speech Speaking Time 6 minutes Preparation Time > 1 minute First Negative Cross-Examination 2 minutes First Negative Speech 6 minutes First Affirmative Cross-Examination 2 minutes Second Affirmative Speech 6 minutes Second Negative Cross-Examination 2 minutes First Negative Rebuttal 3 minutes First Affirmative Rebuttal 4 minutes Second Negative Rebuttal 3 minutes Second Affirmative Rebuttal 3 minutes > 2 minutes > 1 minute > 2 minutes > 1 minute > 2 minutes > 2 minutes > 2 minutes > 2 minutes Note that all formal speakers will be timed and expected to remain within the time limits. Regular competitive debates run in an 8-3-4 minute format but time restrictions require that we reduce the time for our debate to 6-2-3 (with 4 minutes left intact for the difficult First Affirmative Rebuttal). Assignments You have been assigned a side (Affirmative or Negative) and a general role (either Speakers or Researchers). It will be your first duty to determine how you will fill the more specific roles and give your Assignment Sheet to Mrs. Eiserman. Assignment Descriptions First Affirmative Speech: Your job will be to set forth your side’s case in as much detail and clarity as possible. Your speech should be polished and, above all, well-organized and well-supported by evidence. You have the advantage of setting the terms of the debate. First Negative Cross-Ex: Your job is to question the first affirmative speaker in order to (1) clarify the affirmative arguments and (2) raise doubts about the affirmative side’s reasoning and evidence. First Negative Speech: Your job will be to poke holes all through the first affirmative’s case by challenging it on the basis of reasoning and soundness of evidence. You will want to have some solid evidence of your own to counter the affirmative arguments and to support your own arguments that violent revolution is dangerous. First Affirmative Cross-Ex: Like your negative counterpart, your job is to clarify and challenge reasoning and evidence, but through cross-ex of the first negative speaker. Second Affirmative Speech: Your job is to knock down the arguments of the first negative speaker and, if time, build upon the first affirmative’s case. You should have a brief or two prepared in advance both to refute negative arguments and bolster your own. Second Negative Cross-Ex: Same as your colleagues above but also clarify where the affirmative speaker may have missed responding to an argument presented by first negative. Your side can exploit this kind of mistake to its advantage. Second Negative Speech: Your job is to exploit the weakest points in the affirmative case by building on first negative’s arguments, refuting second affirmative’s, and adding more negative arguments of your own. Also, point out where second affirmative failed to respond to your first negative arguments. That ’s a lot to do but remember that no new evidence can be introduced in rebuttals. You’ll need crisp, clear delivery. Second Affirmative Cross-Ex: Same as your second negative colleague above, except that you’re trying to catch where second negative may have missed the boat. This position is important because you’re sandwiched in between two negative speakers. Now’s the time to pull out your bombshell questions to try to trip up the negative side. First Negative Rebuttal: Start wrapping up your side’s arguments by pointing out where (1) the affirmative case is weakest, (2) the affirmative side has failed to respond to challenges by your side, and (3) where your case is strongest. First Affirmative Rebuttal: Vice versa for you but your job is a little tougher because you need to pickup where the second affirmative speaker left off, which is seven minutes worth of negative arguments ago. Second Negative Rebuttal: Counter second affirmative rebuttal and punch up your strong points. You have the last word for your side. No pressure. Second Affirmative Rebuttal: You have the ability to make or break your side’s case by refuting the negative arguments and highlighting your side’s strongest arguments. This slot was made for great orators. You have the final word; make it count. Case Writers: Much like Congressional staffers support their Senator or Representative, your job will be to provide moral, organizational, and drafting support for your side’s speakers. You will help your speakers write up your side’s case and you will work with the research teams to organize research and write briefing papers. You are the organizational linchpin of your side’s efforts. Researchers: Research teams are split up into three different areas - philosophy, the American Revolution, and the French Revolution. Philosophy - Your team will survey Enlightenment-era and even older writings to find evidence to support your side’s arguments. Locke, Rousseau, Montesquieu, Paine, Burke, and even Frederick the Great will prove to be good sources. You may also find information to discredit sources that the other side may use (e.g., Rousseau led a highly questionable lifestyle). American Revolution - The affirmative side can find plenty of evidence here to support the justification of violence (Hint: Start with Jefferson’s greatest written work). The Negative side can find evidence that shows Britain’s efforts to reach a compromise, justification for British taxation policies, and the treasonous conduct of the rebels. French Revolution - Everyone can go to town with this subject. Affirmative researchers can find plenty of evidence to discredit the ancient regime and negative researchers can recount the horrors of the Reign of Terror. Scrimmagers: You get to play devil’s advocate by advising your side on what the other side’s strategy will be. Your major contribution to your team is serving as the stand-ins for the opposing team. You will run through a practice debate with your side’s speakers the day before the actual debate. Grading The entire debate process will count as an interdisciplinary assessment worth 50 points. A description of each of the grading elements is listed below. Preparation (30%) The preparation grade will be based on the following criteria, which are individualized for each type of assignment: * First Affirmative Constructive Speaker: A typed outline of your speech, including citations of evidence. This text should be two-three pages in length, single-spaced. Note that the evidence for your speech will be provided by the research teams. Your main job here is to organize the information and rehearse your speech . The draft version is due no later than Friday, January 28 and the final version is due the day of the debate itself. * Other Speakers: A typed briefing paper (sample attached) of at least two -three full pages in length that could be used in one or both of your team’s constructive speeches. The topic of the briefing paper will be up to you and will likely depend on which research team you choose to work with directly during the research phase. Bear in mind that you will need to avoid duplication of topics/evidence. The draft version is due no later than Friday, January 28 and the final version is due Monday, January 31, 2011. * Case Writers: Same as other speakers above. In addition, you will be asked to meet with Mrs. Eiserman or Mr. Mandel at the end of each research/preparation day to assess your side’s progress and where more work needs to be done. * All Speakers and Case Writers: The four speakers and case writer on each team are also expected to work together to produce a brief, typed outline of their case by the end of class on Friday, January 28. This is not a final version of the case structure by any means but is simply meant to serve as a working document for comment and revision as the research process continues. * Scrimmagers: Each scrimmage team needs to produce a draft outline of the opposing position’s case (by Friday, January 28) and a set of three briefing papers (one for each major topic - philosophy and both revolutions) in preparation for the scrimmage debate on Monday, January 31. Scrimmagers will also need to determine speaker positions by Friday, January 28. * Researchers: A set of twenty research cards per person, drawn from at least three different relevant sources. The first set of ten cards is due by the end of the class period on Tuesday, January 25 and the second set of ten cards is due no later than the start of the class period on Thursday, January 27. Each card must have a proper source citation in MLA format and must include substantive, relevant evidence. When in doubt, check with the instructor to verify whether or not a card passes muster. Once the cards are completed, you will be expected to match up and work with the speakers to organize evidence and help plug gaps in knowledge through targeted research. Work with your team to ensure that research efforts are not duplicated. NOTE that, in all cases, your preparation grade is also dependent on persistent, sustained effort in class. If you complete your written requirements early, you need to help out in some other way, such as gathering more research. The idea here is to complete research and writing for the debate in class as much as possible. Participation (10%) On the day of the debate, you will be graded on your participation in the formal debate (if you are a sp eaker) and on your overall participation as a listener and spirited participant (if you are not a formal speaker). Everyone has a chance to join in the parliamentary-style debate after the formal debate session concludes. Even if you don’t speak at all, you can still earn full credit by actively participating as a listener and vocal supporter of your side. All participants should wear appropriate debate attire (dressy casual is fine; just no jeans, sneakers, or t -shirts). Commentary (10% All non-speakers will be required to take notes of the debate and write a one page commentary on the results of the debate, assessing which side you believe won the debate and why. Make sure that you give a minimum of three concrete examples to support your conclusion. The notes and commentaries are due in class on Wednesday, February 2, at which time we will discuss the debate. Plan of Attack To make effective use of our time, we have designed the following schedule of daily objectives for debate preparation. M Jan 24 (today) Briefing and assignments Mrs. Eiserman takes researchers to the library to gather evidence. Mr. Mandel walks through debate procedure with speakers, case writers, and scrimmagers. T Jan 25 Research/Development of Arguments in Library Speakers and case writers should work with researchers to develop briefing paper ideas. Scrimmagers should research the opposing side’s arguments. Research cards and outlines due by the end of the block W Jan 26 Discussion of the French Revolution in World History Discussion of Chapters 10-16 in English Th Jan 27 Research/Development of Arguments in Library Research cards due at the end of the block. Speakers and case writers should meet with research teams and work to draft briefing papers and first AFF speech. Scrimmagers work on briefing papers with help from researchers. Pursue follow-up research as necessary. F Jan 28 Work to finalize arguments Briefing drafts due M Jan 31 Practice debate with scrimmagers All draft cases/briefs for speakers and case writers due All final briefs for scrimmagers due T Feb 1 Debate! ! ! Dress appropriately All debate materials (including all research cards) due in final W Feb 2 Commentaries/notes due. Debriefing of debate. AP European History Mrs. Eiserman/Mr. Mandell Name: ___________________________________ Third Quarter GRADE REPORT FOR REVOLUTION DEBATE Researchers The overall grade for the Revolution Debate will be determined according to the criteria listed below. Description of Graded Element Pts. Possible Score first set of 10 due by Tuesday, Jan 25 10 _____ second set of 10 due by Thursday, Jan 27 10 _____ 10 _____ 10 _____ 10 _____ Preparation (30 points) Research Cards 1 point for each index card that is fully sourced and contains clear, significant and relevant evidence; three different sources used Points may be deducted for missing elements or late submission Case writer/instructor observation of work habits/usefulness of research Participation 10% * serious and sustained participation in the debate through speaking, active listening, and/or participating in questioning/answering in the parliamentary session (5 pts. based on instructor observation) notes taken on the day of the debate; evidences attentive listening and an effort to track specific arguments through the debate due by Tuesday, February 1 (5pts.) Commentary (10%) due Wednesday, February 2 * typed, one-page, single-spaced commentary provides rationale for which side won the debate and why; offers three specific supports from the debate itself Total Grade: Comments: _____% AP European History Mrs. Eiserman/Mr. Mandell Name: ___________________________________ Third Quarter GRADE REPORT FOR REVOLUTION DEBATE Case writers and Scrimmagers The overall grade for the Revolution Debate will be determined according to the criteria listed below. Description of Graded Element Pts. Possible Case Outline (5 points) due in draft by Thursday, January 27 Score 5 _____ 10 _____ 15 _____ 5 _____ 5 _____ 10 _____ * typed outline that lays out basic approach and arguments that the team intends to research and potentially use in the debate; scrimmagers lay out the opposing position Case Briefs (25 points) due in draft by Friday, January 28 due in final by Tuesday, February 1 *typed brief (or affirmative case) that follows a logical format and includes specific, relevant evidence with full source citation; at least two full pages in length; follows outline format with tag lines and narrative analysis as needed (affirmative case speech text may be typed out in full); scrimmagers must submit final version of three briefing papers total by Friday, January 28 Participation (10 points) * serious and sustained participation in the debate through speaking, active listening, and/or participating in questioning/answering in the parliamentary session (based on instructor observation) notes taken on the day of the debate; demonstrates attentive listening and an effort to track specific arguments through the debate due by Tuesday, February 1 Commentary ((10 points)) due by due Wednesday, February 2 * typed, one-page, single-spaced commentary provides rationale for which side won the debate and why; offers three specific supports from the debate itself Total Grade: Comments: _____ AP European History Mrs. Eiserman/Mr. Mandell Name: ___________________________________ Third Quarter GRADE REPORT FOR REVOLUTION DEBATE Speakers The overall grade for the Revolution Debate will be determined according to the criteria listed below. Case Outline (5 points) due in draft by Thursday, January 27 * typed outline that lays out basic approach and arguments that the team intends to research and potentially use in the debate; scrimmagers lay out the opposing position 5 pts. Case Briefs (25 points) due in draft by Friday, January 28 25 pts. due in final by Tuesday, February 1 *typed brief (or affirmative case) that follows a logical format and includes specific, relevant evidence with full source citation; at least two full pages in length; follows outline format with tag lines and narrative analysis as needed (affirmative case speech text may be typed out in full). _____ _____ Participation (20 points) * serious and sustained participation in the debate through speaking, active listening, and/or participating in questioning/answering in the parliamentary session Total Grade: Comments: 20 pts. _____ _____ Affirmative Negative Negative Speakers/Support Noah Goodwin Amanda Gaylord Amanda Frickie Nick Rudman James Green Hannah Shoultz Olivia Tate Charlie Wall Sinclair Cabocel Andres Mendez Jeff Saulnier Ned Schweikert Colleen Geigle Grace Woodward Meghan Flynn Talia Rosen Researchers Maddie Harple Will Hardy Georgia Carter Stephen Klem Rachel Robertson Emma Jacques Henry Love Catherine Roddy Zolboo Batkholboo Steven Tom Christine Vincent Ryan Whitesides Callie Addison Ryan Cauffman Hillary Jones Adam Land Julie Schroeder Will Horowitz Katy Ouzts J.P. Defranco Emily Spack Theodore Van Dyke K.T. Fiduk Jane Townshend Affirmative Assignments Speaker 1 Speaker 2 Speaker 3 Case Writer 1 Case Writer 2 Case Writer 3 Devil’s Advocate 1 Devil’s Advocate 2 Researchers Locke Rousseau Hobbes Montesquieu Voltaire Boussat Tennis court oath Declaration of independence Burke Jefferson Paine Declaration of rights of man Economy/taxation – causes of revolution Representation – causes of revolution respect/social distinctions Advanced English 9 & World History Mrs. Eiserman & Mr. Mandel Name: ______________________ Third Quarter DEBATING REVOLUTION As the ideas of the Enlightenment philosophers percolated throughout Europe and over into North America in the 1700s, groups of individuals decided to turn ideas on personal liberty and representative government into action. Colonists in North America took the first step toward revolution when they protested the mercantilist policies of the British crown in the 1760s and early 1770s. Disagreement over the issue of taxation without representation led to an armed struggle for independence that began with “the shot heard ‘round the world” at Lexington and Concord in April 1775 and ended with the “world turned upside down” at the Battle of Yorktown in October 1781. The American independence movement set a momentous precedent for the use of violent force to overthrow an unrepresentative government. Within a decade, the French revolution proved that Europe was not immune to revolutionary ideas. The chaos and bloodshed experienced by France from the storming of the Bastille in 1789 until the “election” of Napoleon Bonaparte as First Consul in 1799 raised the question of whether revolutionary ideas could be carried too far. Objective This interdisciplinary lesson will consist of a formal debate on the following resolution. RESOLVED: The use of violent force to overthrow an unrepresentative government is justified. The graded elements of the debate will include preparation, participation, and a written commentary, as described in further detail below. Format The debate format pits one half of your block against the other. One class section will be assigned to the affirmative (yes, violent force is justified; viva la revolution!) and the other to the negative (no, you uncivilized brutes, it is not justified). To add historical flavor, the debate will be set in the British Parliament in the year 1800. (No, you do not have to speak with an accent. Yes, you may, if you wish). In reality, Ministers of Parliament often heatedly debated issues related to the American and French Revolutions. The debate over whether or not revolution was justified usually split down party lines between conservative Tor ies (who thought revolution was dangerous) and liberal Whigs (who often supported the revolutionaries in spirit, even when Britain went to war against “the colonies” and France). Nevertheless, we will need to take some liberties with history because, by 1800, most British MPs were in agreement that revolutionary France posed a threat to British national interests, especially after Napoleon’s invasion of Egypt in 1798. Setting the debate in 1800 provides the advantage of being able to draw upon the history of the French Revolution, including its great achievements and excesses, to support and attack the arguments on both sides. The debate format will be an abbreviated version of that used in debate competition. Four students from each class section will be assigned to share out the formal speaking and questioning roles. Everyone else will be assigned specific research and support roles. Your goal is to work as a team to ensure that your case stands up under the scrutiny of the opposition, as well as your teachers. The formal debate will be held on Tuesday, February 1 and will last approximately sixty minutes. We will reserve thirty minutes for an open parliamentary style question and answer period, in which members of each side can freely challenge other membe rs and make brief statements of their own. The formal debate segment will be run as follows: First Affirmative Speech Speaking Time 6 minutes Preparation Time > 1 minute First Negative Cross-Examination 2 minutes First Negative Speech 6 minutes First Affirmative Cross-Examination 2 minutes Second Affirmative Speech 6 minutes Second Negative Cross-Examination 2 minutes First Negative Rebuttal 3 minutes First Affirmative Rebuttal 4 minutes Second Negative Rebuttal 3 minutes Second Affirmative Rebuttal 3 minutes > 2 minutes > 1 minute > 2 minutes > 1 minute > 2 minutes > 2 minutes > 2 minutes > 2 minutes Note that all formal speakers will be timed and expected to remain within the time limits. Regular competitive debates run in an 8-3-4 minute format but time restrictions require that we reduce the time for our debate to 6-2-3 (with 4 minutes left intact for the difficult First Affirmative Rebuttal). Assignments You have been assigned a side (Affirmative or Negative) and a general role (either Speakers or Researchers). It will be your first duty to determine how you will fill the more specific roles and give your Assignment Sheet to Mrs. Eiserman. Assignment Descriptions First Affirmative Speech: Your job will be to set forth your side’s case in as much detail and clarity as possible. Your speech should be polished and, above all, well-organized and well-supported by evidence. You have the advantage of setting the terms of the debate. First Negative Cross-Ex: Your job is to question the first affirmative speaker in order to (1) clarify the affirmative arguments and (2) raise doubts about the affirmative side’s reasoning and evidence. First Negative Speech: Your job will be to poke holes all through the first affirmative’s case by challenging it on the basis of reasoning and soundness of evidence. You will want to have some solid evidence of your own to counter the affirmative arguments and to support your own arguments that violent revolution is dangerous. First Affirmative Cross-Ex: Like your negative counterpart, your job is to clarify and challenge reasoning and evidence, but through cross-ex of the first negative speaker. Second Affirmative Speech: Your job is to knock down the arguments of the first negative speaker and, if time, build upon the first affirmative’s case. You should have a brief or two prepared in advance both to refute negative arguments and bolster your own. Second Negative Cross-Ex: Same as your colleagues above but also clarify where the affirmative speaker may have missed responding to an argument presented by first negative. Your side can exploit this kind of mistake to its advantage. Second Negative Speech: Your job is to exploit the weakest points in the affirmative case by building on first negative’s arguments, refuting second affirmative’s, and adding more negative arguments of your own. Also, point out where second affirmative failed to respond to your first negative arguments. That’s a lot to do but remember that no new evidence can be introduced in rebuttals. You’ll need crisp, clear delivery. Second Affirmative Cross-Ex: Same as your second negative colleague above, except that you’re trying to catch where second negative may have missed the boat. This position is important because you’re sandwiched in between two negative speakers. Now’s the time to pull out your bombshell questions to try to trip up the negative side. First Negative Rebuttal: Start wrapping up your side’s arguments by pointing out where (1) the affirmative case is weakest, (2) the affirmative side has failed to respond to challenges by your side, and (3) where your case is strongest. First Affirmative Rebuttal: Vice versa for you but your job is a little tougher because you need to pickup where the second affirmative speaker left off, which is seven minutes worth of negative arguments ago. Second Negative Rebuttal: Counter second affirmative rebuttal and punch up your strong points. You have the last word for your side. No pressure. Second Affirmative Rebuttal: You have the ability to make or break your side’s case by refuting the negative arguments and highlighting your side’s strongest arguments. This slot was made for great orators. You have the final word; make it count. Case Writers: Much like Congressional staffers support their Senator or Representative, your job will be to provide moral, organizational, and drafting support for your side’s speakers. You will help your speakers write up your side’s case and you will work with the research teams to organize research and write briefing papers. You are the organizational linchpin of your side’s efforts. Researchers: Research teams are split up into three different areas - philosophy, the American Revolution, and the French Revolution. Philosophy - Your team will survey Enlightenment-era and even older writings to find evidence to support your side’s arguments. Locke, Rousseau, Montesquieu, Paine, Burke, and even Frederick the Great will prove to be good sources. You may also find information to discredit sources that the other side may use (e.g., Rousseau led a highly questionable lifestyle). American Revolution - The affirmative side can find plenty of evidence here to support the justification of violence (Hint: Start with Jefferson’s greatest written work). The Negative side can find evidence that shows Britain’s efforts to reach a compromise, justification for British taxation policies, and the treasonous conduct of the rebels. French Revolution - Everyone can go to town with this subject. Affirmative researchers can find plenty of evidence to discredit the ancient regime and negative researchers can recount the horrors of the Reign of Terror. Scrimmagers: You get to play devil’s advocate by advising your side on what the other side’s strategy will be. Your major contribution to your team is serving as the stand-ins for the opposing team. You will run through a practice debate with your side’s speakers the day before the actual debate. Grading The entire debate process will count as an interdisciplinary assessment worth 50 points. A description of each of the grading elements is listed below. Preparation (30%) The preparation grade will be based on the following criteria, which are individualized for each type of assignment: * First Affirmative Constructive Speaker: A typed outline of your speech, including citations of evidence. This text should be two-three pages in length, single-spaced. Note that the evidence for your speech will be provided by the research teams. Your main job here is to organize the information and rehearse your speech. The draft version is due no later than Friday, January 28 and the final version is due the day of the debate itself. * Other Speakers: A typed briefing paper (sample attached) of at least two -three full pages in length that could be used in one or both of your team’s constructive speeches. The topic of the briefing paper will be up to you and will likely depend on which research team you choose to work with directly during the research phase. Bear in mind that you will need to avoid duplication of topics/evidence. The draft version is due no later than Friday, January 28 and the final version is due Monday, January 31, 2011. * Case Writers: Same as other speakers above. In addition, you will be asked to meet with Mrs. Eiserman or Mr. Mandel at the end of each research/preparation day to assess your side’s progress and where more work needs to be done. * All Speakers and Case Writers: The four speakers and case writer on each team are also expected to work together to produce a brief, typed outline of their case by the end of class on Friday, January 28. This is not a final version of the case structure by any means but is simply meant to serve as a working document for comment and revision as the research process continues. * Scrimmagers: Each scrimmage team needs to produce a draft outline of the opposing position’s case (by Friday, January 28) and a set of three briefing papers (one for each major topic - philosophy and both revolutions) in preparation for the scrimmage debate on Monday, January 31. Scrimmagers will also need to determine speaker positions by Friday, January 28. * Researchers: A set of twenty research cards per person, drawn from at least three different relevant sources. The first set of ten cards is due by the end of the class period on Tuesday, January 25 and the second set of ten cards is due no later than the start of the class period on Thursday, January 27. Each card must have a proper source citation in MLA format and must include substantive, relevant evidence. When in doubt, check with the instructor to verify whether or not a card passes muster. Once the cards are completed, you will be expected to match up and work with the speakers to organize evidence and help plug gaps in knowledge through targeted research. Work with your team to ensure that research efforts are not duplicated. NOTE that, in all cases, your preparation grade is also dependent on persistent, sustained effort in class. If you complete your written requirements early, you need to help out in some other way, such as gathering more research. The idea here is to complete research and writing for the debate in class as much as possible. Participation (10%) On the day of the debate, you will be graded on your participation in the formal debate (if you are a speaker) and on your overall participation as a listener and spirited participant (if you are not a formal speaker). Everyone has a chance to join in the parliamentary-style debate after the formal debate session concludes. Even if you don’t speak at all, you can still earn full credit by actively participating as a listener and vocal supporter of your side. All participants should wear appropriate debate attire (dressy casual is fine; just no jeans, sneakers, or t-shirts). Commentary (10% All non-speakers will be required to take notes of the debate and write a one page commentary on the results of the debate, assessing which side you believe won the debate and why. Make sure that you give a minimum of three concrete examples to support your conclusion. The notes and commentaries are due in class on Wednesday, February 2, at which time we will discuss the debate. Plan of Attack To make effective use of our time, we have designed the following schedule of daily objectives for debate preparation. M Jan 24 (today) Briefing and assignments Mrs. Eiserman takes researchers to the library to gather evidence. Mr. Mandel walks through debate procedure with speakers, case writers, and scrimmagers. T Jan 25 Research/Development of Arguments in Library Speakers and case writers should work with researchers to develop briefing paper ideas. Scrimmagers should research the opposing side’s arguments. Research cards and outlines due by the end of the block W Jan 26 Discussion of the French Revolution in World History Discussion of Chapters 10-16 in English Th Jan 27 Research/Development of Arguments in Library Research cards due at the end of the block. Speakers and case writers should meet with research teams and work to draft briefing papers and first AFF speech. Scrimmagers work on briefing papers with help from researchers. Pursue follow-up research as necessary. F Jan 28 Work to finalize arguments Briefing drafts due M Jan 31 Practice debate with scrimmagers All draft cases/briefs for speakers and case writers due All final briefs for scrimmagers due T Feb 1 Debate! ! ! Dress appropriately All debate materials (including all research cards) due in final W Feb 2 Commentaries/notes due. Debriefing of debate. AP European History Mrs. Eiserman/Mr. Mandell Name: ___________________________________ Third Quarter GRADE REPORT FOR REVOLUTION DEBATE Researchers The overall grade for the Revolution Debate will be determined according to the criteria listed below. Description of Graded Element Pts. Possible Score first set of 10 due by Tuesday, Jan 25 10 _____ second set of 10 due by Thursday, Jan 27 10 _____ 10 _____ 10 _____ 10 _____ Preparation (30 points) Research Cards 1 point for each index card that is fully sourced and contains clear, significant and relevant evidence; three different sources used Points may be deducted for missing elements or late submission Case writer/instructor observation of work habits/usefulness of research Participation 10% * serious and sustained participation in the debate through speaking, active listening, and/or participating in questioning/answering in the parliamentary session (5 pts. based on instructor observation) notes taken on the day of the debate; evidences attentive listening and an effort to track specific arguments through the debate due by Tuesday, February 1 (5pts.) Commentary (10%) due Wednesday, February 2 * typed, one-page, single-spaced commentary provides rationale for which side won the debate and why; offers three specific supports from the debate itself Total Grade: Comments: _____% AP European History Mrs. Eiserman/Mr. Mandell Name: ___________________________________ Third Quarter GRADE REPORT FOR REVOLUTION DEBATE Case writers and Scrimmagers The overall grade for the Revolution Debate will be determined according to the criteria listed below. Description of Graded Element Pts. Possible Case Outline (5 points) due in draft by Thursday, January 27 Score 5 _____ 10 _____ 15 _____ 5 _____ 5 _____ 10 _____ * typed outline that lays out basic approach and arguments that the team intends to research and potentially use in the debate; scrimmagers lay out the opposing position Case Briefs (25 points) due in draft by Friday, January 28 due in final by Tuesday, February 1 *typed brief (or affirmative case) that follows a logical format and includes specific, relevant evidence with full source citation; at least two full pages in length; follows outline format with tag lines and narrative analysis as needed (affirmative case speech text may be typed out in full); scrimmagers must submit final version of three briefing papers total by Friday, January 28 Participation (10 points) * serious and sustained participation in the debate through speaking, active listening, and/or participating in questioning/answering in the parliamentary session (based on instructor observation) notes taken on the day of the debate; demonstrates attentive listening and an effort to track specific arguments through the debate due by Tuesday, February 1 Commentary ((10 points)) due by due Wednesday, February 2 * typed, one-page, single-spaced commentary provides rationale for which side won the debate and why; offers three specific supports from the debate itself Total Grade: Comments: _____ AP European History Mrs. Eiserman/Mr. Mandell Name: ___________________________________ Third Quarter GRADE REPORT FOR REVOLUTION DEBATE Speakers The overall grade for the Revolution Debate will be determined according to the criteria listed below. Case Outline (5 points) due in draft by Thursday, January 27 * typed outline that lays out basic approach and arguments that the team intends to research and potentially use in the debate; scrimmagers lay out the opposing position 5 pts. Case Briefs (25 points) due in draft by Friday, January 28 25 pts. due in final by Tuesday, February 1 *typed brief (or affirmative case) that follows a logical format and includes specific, relevant evidence with full source citation; at least two full pages in length; follows outline format with tag lines and narrative analysis as needed (affirmative case speech text may be typed out in full). _____ _____ Participation (20 points) * serious and sustained participation in the debate through speaking, active listening, and/or participating in questioning/answering in the parliamentary session Total Grade: Comments: 20 pts. _____ _____ Affirmative Negative Negative Speakers/Support Noah Goodwin Amanda Gaylord Amanda Frickie Nick Rudman James Green Hannah Shoultz Olivia Tate Charlie Wall Sinclair Cabocel Andres Mendez Jeff Saulnier Ned Schweikert Colleen Geigle Grace Woodward Meghan Flynn Talia Rosen Researchers Maddie Harple Will Hardy Georgia Carter Stephen Klem Rachel Robertson Emma Jacques Henry Love Catherine Roddy Zolboo Batkholboo Steven Tom Christine Vincent Ryan Whitesides Callie Addison Ryan Cauffman Hillary Jones Adam Land Julie Schroeder Will Horowitz Katy Ouzts J.P. Defranco Emily Spack Theodore Van Dyke K.T. Fiduk Jane Townshend Affirmative Assignments Speaker 1 Speaker 2 Speaker 3 Case Writer 1 Case Writer 2 Case Writer 3 Devil’s Advocate 1 Devil’s Advocate 2 Researchers Locke Rousseau Hobbes Montesquieu Voltaire Boussat Tennis court oath Declaration of independence Burke Jefferson Paine Declaration of rights of man Economy/taxation – causes of revolution Representation – causes of revolution respect/social distinctions Advanced English 9 & World History Mrs. Eiserman & Mr. Mandel Name: ______________________ Third Quarter DEBATING REVOLUTION As the ideas of the Enlightenment philosophers percolated throughout Europe and over into North America in the 1700s, groups of individuals decided to turn ideas on personal liberty and representative government into action. Colonists in North America took the first step toward revolution when they protested the mercantilist policies of the British crown in the 1760s and early 1770s. Disagreement over the issue of taxation without representation led to an armed struggle for independence that began with “the shot heard ‘round the world ” at Lexington and Concord in April 1775 and ended with the “world turned upside down” at the Battle of Yorktown in Oc tober 1781. The American independence movement set a momentous precedent for the use of violent force to overthrow an unrepresentative government. Within a decade, the French revolution proved that Europe was not immune to revolutionary ideas. The chaos and bloodshed experienced by France from the storming of the Bastille in 1789 until the “election” of Napoleon Bonaparte as First Consul in 1799 raised the question of whether revolutionary ideas could be carried too far. Objective This interdisciplinary lesson will consist of a formal debate on the following resolution. RESOLVED: The use of violent force to overthrow an unrepresentative government is justified. The graded elements of the debate will include preparation, participation, and a written commentary, as described in further detail below. Format The debate format pits one half of your block against the other. One class section will be assigned to the affirmative (yes, violent force is justified; viva la revolution!) and the other to the negative (no, you uncivilized brutes, it is not justified). To add historical flavor, the debate will be set in the British Parliament in the yea r 1800. (No, you do not have to speak with an accent. Yes, you may, if you wish). In reality, Ministers of Parliament often heatedly debated issues related to the American and French Revolutions. The debate over whether or not revolution was justified usually split down party lines between conservative Tories (who thought revolution was dangerous) and liberal Whigs (who often supported the revolutionaries in spirit, even when Britain went to war against “the colonies” and France). Nevertheless, we will need to take some liberties with history because, by 1800, most British MPs were in agreement that revolutionary France posed a threat to British national interests, especially after Napoleon’s invasion of Egypt in 1798. Setting the debate in 1800 provides the advantage of being able to draw upon the history of the French Revolution, including its great achievements and excesses, to support and attack the arguments on both sides. The debate format will be an abbreviated version of that used in debate competition. Four students from each class section will be assigned to share out the formal speaking and questioning roles. Everyone else will be assigned specific research and support roles. Your goal is to work as a team to ensure that your case stands up under the scrutiny of the opposition, as well as your teachers. The formal debate will be held on Tuesday, February 1 and will last approximately sixty minutes. We will reserve thirty minutes for an open parliamentary style question and answer period, in which members of each side can freely challenge other members and make brief statements of their own. The formal debate segment will be run as follows: First Affirmative Speech Speaking Time 6 minutes Preparation Time > 1 minute First Negative Cross-Examination 2 minutes First Negative Speech 6 minutes First Affirmative Cross-Examination 2 minutes Second Affirmative Speech 6 minutes Second Negative Cross-Examination 2 minutes First Negative Rebuttal 3 minutes First Affirmative Rebuttal 4 minutes Second Negative Rebuttal 3 minutes Second Affirmative Rebuttal 3 minutes > 2 minutes > 1 minute > 2 minutes > 1 minute > 2 minutes > 2 minutes > 2 minutes > 2 minutes Note that all formal speakers will be timed and expected to remain within the time limits. Regular competitive debates run in an 8-3-4 minute format but time restrictions require that we reduce the time for our debate to 6-2-3 (with 4 minutes left intact for the difficult First Affirmative Rebuttal). Assignments You have been assigned a side (Affirmative or Negative) and a general role (either Speakers or Researchers). It will be your first duty to determine how you will fill the more specific roles and give your Assignment Sheet to Mrs. Eiserman. Assignment Descriptions First Affirmative Speech: Your job will be to set forth your side’s case in as much detail and clarity as possible. Your speech should be polished and, above all, well-organized and well-supported by evidence. You have the advantage of setting the terms of the debate. First Negative Cross-Ex: Your job is to question the first affirmative speaker in order to (1) clarify the affirmative arguments and (2) raise doubts about the affirmative side’s reasoning and evidence. First Negative Speech: Your job will be to poke holes all through the first affirmative’s case by challenging it on the basis of reasoning and soundness of evidence. You will want to have some solid evidence of your own to counter the affirmative arguments and to support your own arguments that violent revolution is dangerous. First Affirmative Cross-Ex: Like your negative counterpart, your job is to clarify and challenge reasoning and evidence, but through cross-ex of the first negative speaker. Second Affirmative Speech: Your job is to knock down the arguments of the first negative speaker and, if time, build upon the first affirmative’s case. You should have a brief or two prepared in advance both to refute negative arguments and bolster your own. Second Negative Cross-Ex: Same as your colleagues above but also clarify where the affirmative speaker may have missed responding to an argument presented by first negative. Your side can exploit this kind of mistake to its advantage. Second Negative Speech: Your job is to exploit the weakest points in the affirmative case by building on first negative’s arguments, refuting second affirmative’s, and adding more negative arguments of your own. Also, point out where second affirmative failed to respond to your first negative arguments. That’s a lot to do but remember that no new evidence can be introduced in rebuttals. You’ll need crisp, clear delivery. Second Affirmative Cross-Ex: Same as your second negative colleague above, except that you’re trying to catch where second negative may have missed the boat. This position is important because you’re sandwiched in between two negative speakers. Now’s the time to pull out your bombshell questions to try to trip up the negative side. First Negative Rebuttal: Start wrapping up your side’s arguments by pointing out where (1) the affirmative case is weakest, (2) the affirmative side has failed to respond to challenges by your side, and (3) where your case is strongest. First Affirmative Rebuttal: Vice versa for you but your job is a little tougher because you need to pickup where the second affirmative speaker left off, which is seven minutes worth of negative arguments ago. Second Negative Rebuttal: Counter second affirmative rebuttal and punch up your strong points. You have the last word for your side. No pressure. Second Affirmative Rebuttal: You have the ability to make or break your side’s case by refuting the negative arguments and highlighting your side’s strongest arguments. This slot was made for great orators. You have the final word; make it count. Case Writers: Much like Congressional staffers support their Senator or Representative, your job will be to provide moral, organizational, and drafting support for your side’s speakers. You will help your speakers write up your side’s case and you will work with the research teams to organize research and write briefing papers. You are the organizational linchpin of your side’s efforts. Researchers: Research teams are split up into three different areas - philosophy, the American Revolution, and the French Revolution. Philosophy - Your team will survey Enlightenment-era and even older writings to find evidence to support your side’s arguments. Locke, Rousseau, Montesquieu, Paine, Burke, and even Frederick the Great will prove to be good sources. You may also find information to discredit sources that the other side may use (e.g., Rousseau led a highly questionable lifestyle). American Revolution - The affirmative side can find plenty of evidence here to support the justification of violence (Hint: Start with Jefferson’s greatest written work). The Negative side can find evidence that shows Britain’s efforts to reach a compromise, justification for British taxation policies, and the treasonous conduct of the rebels. French Revolution - Everyone can go to town with this subject. Affirmative researchers can find plenty of evidence to discredit the ancient regime and negative researchers can recount the horrors of the Reign of Terror. Scrimmagers: You get to play devil’s advocate by advising your side on what the other side’s strategy will be. Your major contribution to your team is serving as the stand-ins for the opposing team. You will run through a practice debate with your side’s speakers the day before the actual debate. Grading The entire debate process will count as an interdisciplinary assessment worth 50 points. A description of each of the grading elements is listed below. Preparation (30%) The preparation grade will be based on the following criteria, which are individualized for each type of assignment: * First Affirmative Constructive Speaker: A typed outline of your speech, including citations of evidence. This text should be two-three pages in length, single-spaced. Note that the evidence for your speech will be provided by the research teams. Your main job here is to organize the information and rehearse your speech. The draft version is due no later than Friday, January 28 and the final version is due the day of the debate itself. * Other Speakers: A typed briefing paper (sample attached) of at least two-three full pages in length that could be used in one or both of your team’s constructive speeches. The topic of the briefing paper will be up to you and will likely depend on which research team you choose to work with directly during the research phase. Bear in mind that you will need to avoid duplication of topics/evidence. The draft version is due no later than Friday, January 28 and the final version is due Monday, January 31, 2011. * Case Writers: Same as other speakers above. In addition, you will be asked to meet with Mrs. Eiserman or Mr. Mandel at the end of each research/preparation day to assess your side’s progress and where more work needs to be done. * All Speakers and Case Writers: The four speakers and case writer on each team are also expected to work together to produce a brief, typed outline of their case by the end of class on Friday, January 28. This is not a final version of the case structure by any means but is simply meant to serve as a workin g document for comment and revision as the research process continues. * Scrimmagers: Each scrimmage team needs to produce a draft outline of the opposing position’s case (by Friday, January 28) and a set of three briefing papers (one for each major topic - philosophy and both revolutions) in preparation for the scrimmage debate on Monday, January 31. Scrimmagers will also need to determine speaker positions by Friday, January 28. * Researchers: A set of twenty research cards per person, drawn from at least three different relevant sources. The first set of ten cards is due by the end of the class period on Tuesday, January 25 and the second set of ten cards is due no later than the start of the class period on Thursday, January 27. Each card must have a proper source citation in MLA format and must include substantive, relevant evidence. When in doubt, check with the instructor to verify whether or not a card passes muster. Once the cards are completed, you will be expected to match up and work with the speakers to organize evidence and help plug gaps in knowledge through targeted research. Work with your team to ensure that research efforts are not duplicated. NOTE that, in all cases, your preparation grade is also dependent on persistent, sustained effort in class. If you complete your written requirements early, you need to help out in some other way, such as gathering more research. The idea here is to complete research and writing for the debate in class as much as possible. Participation (10%) On the day of the debate, you will be graded on your participation in the formal debate (if you are a speaker) and on your overall participation as a listener and spirited participant (if you are not a formal speaker). Everyone has a chance to join in the parliamentary-style debate after the formal debate session concludes. Even if you don’t speak at all, you can still earn full credit by actively participating as a listener and vocal supporter of your side. All participants should wear appropriate debate attire (dressy casual is fine; just no jeans, sneakers, or t-shirts). Commentary (10% All non-speakers will be required to take notes of the debate and write a one page commentary on the results of the debate, assessing which side you believe won the debate and why. Make sure that you give a minimum of three concrete examples to support your conclusion. The notes and commentaries are due in class on Wednesday, February 2, at which time we will discuss the debate. Plan of Attack To make effective use of our time, we have designed the following schedule of daily objectives for debate preparation. M Jan 24 (today) Briefing and assignments Mrs. Eiserman takes researchers to the library to gather evidence. Mr. Mandel walks through debate procedure with speakers, case writers, and scrimmagers. T Jan 25 Research/Development of Arguments in Library Speakers and case writers should work with researchers to develop briefing paper ideas. Scrimmagers should research the opposing side’s arguments. Research cards and outlines due by the end of the block W Jan 26 Discussion of the French Revolution in World History Discussion of Chapters 10-16 in English Th Jan 27 Research/Development of Arguments in Library Research cards due at the end of the block. Speakers and case writers should meet with research teams and work to draft briefing papers and first AFF speech. Scrimmagers work on briefing papers with help from researchers. Pursue follow-up research as necessary. F Jan 28 Work to finalize arguments Briefing drafts due M Jan 31 Practice debate with scrimmagers All draft cases/briefs for speakers and case writers due All final briefs for scrimmagers due T Feb 1 Debate! ! ! Dress appropriately All debate materials (including all research cards) due in final W Feb 2 Commentaries/notes due. Debriefing of debate. AP European History Mrs. Eiserman/Mr. Mandell Name: ___________________________________ Third Quarter GRADE REPORT FOR REVOLUTION DEBATE Researchers The overall grade for the Revolution Debate will be determined according to the criteria listed below. Description of Graded Element Pts. Possible Score first set of 10 due by Tuesday, Jan 25 10 _____ second set of 10 due by Thursday, Jan 27 10 _____ 10 _____ 10 _____ 10 _____ Preparation (30 points) Research Cards 1 point for each index card that is fully sourced and contains clear, significant and relevant evidence; three different sources used Points may be deducted for missing elements or late submission Case writer/instructor observation of work habits/usefulness of research Participation 10% * serious and sustained participation in the debate through speaking, active listening, and/or participating in questioning/answering in the parliamentary session (5 pts. based on instructor observation) notes taken on the day of the debate; evidences attentive listening and an effort to track specific arguments through the debate due by Tuesday, February 1 (5pts.) Commentary (10%) due Wednesday, February 2 * typed, one-page, single-spaced commentary provides rationale for which side won the debate and why; offers three specific supports from the debate itself Total Grade: Comments: _____% AP European History Mrs. Eiserman/Mr. Mandell Name: ___________________________________ Third Quarter GRADE REPORT FOR REVOLUTION DEBATE Case writers and Scrimmagers The overall grade for the Revolution Debate will be determined according to the criteria listed below. Description of Graded Element Pts. Possible Case Outline (5 points) due in draft by Thursday, January 27 Score 5 _____ 10 _____ 15 _____ 5 _____ 5 _____ 10 _____ * typed outline that lays out basic approach and arguments that the team intends to research and potentially use in the debate; scrimmagers lay out the opposing position Case Briefs (25 points) due in draft by Friday, January 28 due in final by Tuesday, February 1 *typed brief (or affirmative case) that follows a logical format and includes specific, relevant evidence with full source citation; at least two full pages in length; follows outline format with tag lines and narrative analysis as needed (affirmative case speech text may be typed out in full); scrimmagers must submit final version of three briefing papers total by Friday, January 28 Participation (10 points) * serious and sustained participation in the debate through speaking, active listening, and/or participating in questioning/answering in the parliamentary session (based on instructor observation) notes taken on the day of the debate; demonstrates attentive listening and an effort to track specific arguments through the debate due by Tuesday, February 1 Commentary ((10 points)) due by due Wednesday, February 2 * typed, one-page, single-spaced commentary provides rationale for which side won the debate and why; offers three specific supports from the debate itself Total Grade: Comments: _____ AP European History Mrs. Eiserman/Mr. Mandell Name: ___________________________________ Third Quarter GRADE REPORT FOR REVOLUTION DEBATE Speakers The overall grade for the Revolution Debate will be determined according to the criteria listed below. Case Outline (5 points) due in draft by Thursday, January 27 * typed outline that lays out basic approach and arguments that the team intends to research and potentially use in the debate; scrimmagers lay out the opposing position 5 pts. Case Briefs (25 points) due in draft by Friday, January 28 25 pts. due in final by Tuesday, February 1 *typed brief (or affirmative case) that follows a logical format and includes specific, relevant evidence with full source citation; at least two full pages in length; follows outline format with tag lines and narrative analysis as needed (affirmative case speech text may be typed out in full). _____ _____ Participation (20 points) * serious and sustained participation in the debate through speaking, active listening, and/or participating in questioning/answering in the parliamentary session Total Grade: Comments: 20 pts. _____ _____ Affirmative Negative Negative Speakers/Support Noah Goodwin Amanda Gaylord Amanda Frickie Nick Rudman James Green Hannah Shoultz Olivia Tate Charlie Wall Sinclair Cabocel Andres Mendez Jeff Saulnier Ned Schweikert Colleen Geigle Grace Woodward Meghan Flynn Talia Rosen Researchers Maddie Harple Will Hardy Georgia Carter Stephen Klem Rachel Robertson Emma Jacques Henry Love Catherine Roddy Zolboo Batkholboo Steven Tom Christine Vincent Ryan Whitesides Callie Addison Ryan Cauffman Hillary Jones Adam Land Julie Schroeder Will Horowitz Katy Ouzts J.P. Defranco Emily Spack Theodore Van Dyke K.T. Fiduk Jane Townshend Affirmative Assignments Speaker 1 Speaker 2 Speaker 3 Case Writer 1 Case Writer 2 Case Writer 3 Devil’s Advocate 1 Devil’s Advocate 2 Researchers Locke Rousseau Hobbes Montesquieu Voltaire Boussat Tennis court oath Declaration of independence Burke Jefferson Paine Declaration of rights of man Economy/taxation – causes of revolution Representation – causes of revolution respect/social distinctions Negative Assignments Speaker 1 Speaker 2 Speaker 3 Case Writer 1 Case Writer 2 Case Writer 3 Devil’s Advocate 1 Devil’s Advocate 2 Researchers Locke Rousseau Hobbes Montesquieu Voltaire Boussat Tennis court oath Declaration of independence Burke Jefferson Paine Declaration of rights of man Economy/taxation – causes of revolution Representation – causes of revolution respect/social distinctions