VR-19-1981 - Northern Ireland Court Service Online

advertisement

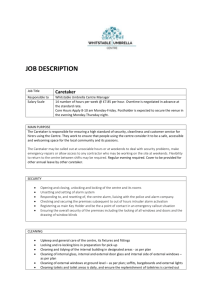

LANDS TRIBUNAL FOR NORTHERN IRELAND LANDS TRIBUNAL AND COMPENSATION ACT (NORTHERN IRELAND) 1964 IN THE MATTER OF AN APPEAL AGAINST VALUATION FOR RATING PURPOSES VR/19/1981 BETWEEN HUGH G KIRKER - APPELLANT AND THE COMMISSIONER OF VALUATION FOR NORTHERN IRELAND - RESPONDENT Lands Tribunal for Northern Ireland - Sir Frank Harrison MBE QC DL Belfast - 22nd October 1982 This appeal was against the decision of the Commissioner of Valuation on first appeal whereby he refused to distinguish a dwelling-house at Carmavy Road, Ballyrobin in the Antrim District as exempt under the provisions of Article 41(2)(a), (c) or (d) of the Rates (Northern Ireland) Order 1977. Appearances Ferriss, instructed by Holmes & Swann, Solicitors, appeared for the appellant and called Mr Hugh Gilbert Kirker as a witness. Mrs McDowell, instructed by the Crown Solicitor, appeared for the Commissioner of Valuation. The hereditament was together with the graveyard vested in six trustees appointed on 24 th February 1979 as trustees of the Carmavy Graveyard by the last survivor of an earlier body of trustees. The house was built some time after 1872 with a side wall which forms part of the wall enclosing the graveyard, which covers about 1 acre. The house has a garden at the rear lying outside the graveyard. The entrances to both house and graveyard are on Carmavy Road and the graveyard has an entrance gate. The entire graveyard is in well kept grass and many headstones bear witness to burials there before 1773, and there has been a Carmavy Graveyard Committee in existence since -1- before 1872. Minute books going back to that date were in evidence, and the present trustees make up 6 out of the 9 members of the Committee. There is no formal constitution setting forth the trusts on which the house and graveyard are held, and no rules or byelaws prescribing the function of the Committee, or governing its procedures. Mr Kirker, who gave evidence, is the present secretary of the Committee of which he has been a member for some 44 years and the Tribunal accepts his evidence that the function and duty of the Committee is to manage and preserve the graveyard premises on behalf of the Trustees in whom the property is vested, and to make plots available to those who require them. The dwelling-house, for as long as Mr Kirker could remember, has been used to accommodate a caretaker (and his wife) who had duties on behalf of the then Committee to keep the graveyard tidy, to open and close graves and carry out other duties allotted by the Committee. A succession of caretakers (four of whom were named) preceded the present residents Mr William Anderson and his wife. On 11th March 1963 His Honour Judge William Johnson, QC, in proceedings to enforce payment of a rate in respect of the dwelling-house gave a written judgement (produced in evidence) in which he held the hereditament to be occupied, not by the then caretaker, but by the Committee which employed him, on the ground that the written agreement made between that Committee and the caretaker required residence in the house "with a view to the more efficient performance of the duties, or services imposed". That caretaker was a labourer in full-time outside employment and gave only part-time services to the Committee. Other caretakers were engaged on similar terms with a similar requirement to reside and the dwelling-house was never vacant until late 1977 or 1978 when outside contractors were for a short time (not more than a year) employed to cut the grass and keep the grounds of the graveyard in order. This method of upkeep proved unsatisfactory and the dwelling-house was modernised with a view to installing a resident caretaker on the old basis. While the work of modernisation was in progress, Mr Anderson applied to the Committee for appointment. He was then living in poor accommodation on the "7 mile straight" beyond Muckamore, and wanted a better house. He was known to the Committee as a good -2- worker and was appointed on 4th March 1979 under an agreement in writing which provided inter alia ".....shall enter into the use and occupation ... of ALL THAT the dwelling-house and premises being the Caretaker's residence upon the said Carmavy Graveyard such user and occupation to be for the more convenient discharge of the duties hereinafter mentioned of the said William Anderson and to be in the capacity of servant and caretaker and not that of Tenant and to terminate as hereinafter mentioned the said William Anderson hereby undertaking to attend at all burials in the said graveyard to open and close all graves when so requested by the Committee and to keep the said graveyard in a tidy condition at all times not to reside at any place other than the dwelling-house on the premises without the consent of the Committee not unreasonably to leave the premises unattended without the consent of the committee and also undertaking immediately on the termination of the said employment and service or whenever required so to do to give up the clear and peaceable possession of the said dwelling-house and premises to the said committee their successors or assigns...." Since that date his residence in the hereditament has been in pursuance of that agreement and his duties have been part-time as he has also been in full-time employment under the Department of the Environment. During his absence from the hereditament his wife performs those duties. All the 300 or so grave plots (with two grave spaces per plot) have been taken and some 10 or 12 burials per year take place in previously used graves. As a general rule, Mr Anderson opens and closes each grave, and is paid a fee by the family which can elect to employ a different grave digger. Mr Anderson has his own lawn-mower and provides his own tools and equipment, all of which are kept in an unused vault in the graveyard. He can choose his own time to carry out his work deciding how the work has to be done, but under the general control of the Committee. The requirement of constant attendance on the premises arose because the Committee had no office or place of business and the caretaker relays messages and also his presence gives protection against vandalism. -3- Mr Anderson has given satisfaction and is regarded as a good worker. As a term of appointment, he was also required to make available a room on the ground floor of the house for Committee meetings which are held about twice per year. The room has a few chairs and a form all belonging to the Andersons, and no other furniture. The Committee gives Mrs Anderson about a week's notice prior to each meeting. The graveyard is padlocked and opened and closed every day by Mr Anderson who receives enquiries concerning proposed burials. There is no denominational, geographical, or other restriction on who may be buried in an available space, but most burials are of people who have family connections with particular plots. The accounts of the Committee over four years 1978-1981 were in evidence and it is not necessary to say more than that the graveyard is not conducted for profit. There is only income from subscriptions, bank interest, and some £28.22 annually from a small holding of War Loan stock. No charge is made for the right to bury in an available grave space. The hereditament has never been rated and the graveyard is not a hereditament for rating purposes, see Schedule 11 Item 10 of the Rates (Northern Ireland) Order 1977. The Tribunal inspected the graveyard and the hereditament. Ferriss submitted that:1. The appointment of Mr Anderson was as "a servant and caretaker" who was bound to reside in the hereditament and nowhere else, so as to assist materially the Committee in the discharge of its function. It was a term of such appointment that the premises were not to be left unattended at any time without consent. The Committee were the occupiers for rating purposes. 2. The only consideration for performance of the job was the provision of the accommodation. That accommodation was provided as an essential part of the job and the purpose for which the provision was made was for the occupier's purpose and no other purpose. -4- 3. The provisions regarding consent to reside elsewhere, or to leave the premises unattended contemplated (inter alia) "not unreasonable" temporary absence, and while unexercised did not alter the character of the occupation. 4. The agreement was a contract for services which left the mode and manner in which the services were to be performed to the servant, who also had to provide whatever equipment and tools were required, but constant attendance throughout every day was required. 5. Mr Anderson was not an employee as defined in Article 41(9) and there was no use for "domestic purposes" as defined there since there was no "contract of service". The only contract was embodied in the written agreement for services to be rendered by the servant. Therefore no apportionment under Article 41(3) was required. 6. If Mr Anderson could be regarded as an independent contractor or a licensee providing services for the Committee, the principle in Glasgow Corporation v Johnstone & Others [1965] AC 609 would apply and his residence under the agreement would be as a matter of "genuine obligation" so as the better to perform the duties imposed. The purpose would be to have those duties performed "on the spot", by providing accommodation which made that possible. 7. The Committee were in rateable occupation, and as a Committee for the maintenance of a graveyard were in law a charity whose main objects were charitable and the hereditament was used wholly (or mainly) for those main objects, the hereditament should be distinguished as exempt under Article 41(2)(c). 8. It was also to be distinguished under Article 41(2)(d), as the Committee was also a body not established or conducted for profit. 9. The hereditament was shown to be used wholly for purposes under Article 41(2)(c) or (d) and thus no apportionment under Article 41(3) was required. Mrs McDowell submitted that:1. The test whether Mr Anderson or the Committee was in rateable occupation was established in Glasgow Corporation v Johnstone & Others [1965] AC 609 and in -5- particular in the speech of Lord Hodson at p 626, and the Portora Royal School case [1970] NI 89 Lord Upjohn at p 137. 2. The provision for consent to reside elsewhere than in the hereditament showed that the Committee did not regard residence either as essential, or of material assistance to their purposes. 3. The light and occasional nature of the duties imposed supported this interpretation. 4. The agreement, if it created a master/servant relationship was a "contract of service", but it should be construed as creating only a licence to occupy at will, which would not be within the master/servant relationship required to make the Johnstone case principle applicable. 5. If the user was sufficient to bring Article 41(2)(c) or (d) into operation, then apportionment under Article 41(3) must be effected so as to apply 50% exemption to the user for "the residential domestic purposes". (The Tribunal queried how such user in this case was to be distinguished from user for the Committee's purposes if residential user was of material assistance to those purposes. Decision Though there was no formal declaration of trust there was clear evidence that both the graveyard and the dwelling-house were vested in the trustees for the time being for the purpose of maintaining the graveyard. That in law is a good charitable purpose. This purpose has been carried out by a succession of committees of management which have employed a resident caretaker who has carried out the work of upkeep and kept the premises secure. At one time recently and for a short period only, the physical maintenance work was entrusted to a contractor but when this proved unsatisfactory the then Committee modernised the house with a view to installing a resident caretaker and reverted to the old procedure. -6- The present caretaker is employed under a written agreement made with him on 4th March 1979 under which he was "to enter into the use and occupation" of the house ".....for the more convenient discharge of the duties hereinafter mentioned...." "and to be in the capacity of servant and caretaker and not that of tenant" and is required "not to reside at any place other than the dwelling-house on the premises without consent of the Committee not unreasonably to leave the premises unattended without the consent of the Committee". His "use and occupation" thus was coupled with the obligation to reside there in the absence of such consent, and no other consideration was paid. Some of his duties are expressed in the written agreement, but these are not exhaustive as he was also required to open and close the gate daily, to answer enquiries and to convey messages to the Committee and to make available a room in the dwelling-house for two or so Committee meetings annually, and to protect the graveyard against vandalism. The caretaker was in full-time outside employment and it was also part of the terms of engagement that his wife should in his absence carry out his obligations and she does so. It may be seen that the duties as thus expressed involve not only the physical work of keeping grass cut and the graveyard tidy, opening and closing graves, but also the routine opening and closing the gate daily to admit the public and at all hours provide the channel of communication between the public and the Committee, coupled with the day and night duty of keeping the graveyard secure against intruders. The question which the Tribunal is faced with is whether the obligation to reside is an integral part of the relationship created by the contract of employment so that the residence in the hereditament is of material assistance to the Committee. Or to put it another way whether the obligation is collateral to the main purpose of the contract of employment, or is a genuine obligation imposed by the Committee for the better performance of the caretaker's duties. The answer determines who is to be regarded as the occupier for rating purposes. The answer seems to the Tribunal to be quite clear. Once it is seen that the active and passive duties apart from the physical work in graveyard, are to be present "on the spot" at all hours to answer queries and act as the channel of communication, and by such presence there to deter possible intruders, it can be seen that -7- the degree of assistance given to the Committee's purposes by residence in the house is of a material degree, and to this is added some use of the house for Committee meetings. It is also not a matter of privilege or mere permission to reside and though the agreement gives a roof over the heads of the caretaker and his wife this is not provided primarily for their convenience, but for the due discharge of the Committee's function in relation to their duties of proper control and maintenance. The necessary ingredients of occupation, user, purpose and consequence are all present and point to the occupation, though residential, being for the due discharge of the Committee's functions. This factual determination makes it unnecessary to deal with the respondent's arguments which involved matters of fact, but it was also argued that the written agreement did not oblige Mr Anderson to reside in the dwelling-house, as with the Committee's consent, he could reside elsewhere. But this was not an option to reside elsewhere, and residence was not at his will and pleasure and he was not free to make whatever use of the house he pleased by shutting the door to the public or on the occasion of Committee meetings. In the opinion of the Tribunal the provisions regarding consent to reside elsewhere, and to be absent "not unreasonably" with consent, do not reduce the paramount obligations in those respects anymore than the undertaking "to give up clear and peaceable possession of the dwelling-house ... whenever required". Each of these provisions related to a time when a change in circumstances takes place, and the obligation to reside for the Committee's purposes is fully operative until that obligation ceases or is varied by consent. Quite apart from these considerations it seems to the Tribunal possible to regard Mr Anderson as "a person ... acting on behalf of...." the Committee which is a body not established or conducted for profit within Article 43(2)(d) so that his "occupation" of the hereditament would by definition be the occupation of the Committee, see Article 41(9) first paragraph, and this point may have to be considered on some other occasion. As regards Article 41(3) apportionment is only required in respect of actual use for such of the exempting purposes as are "domestic purposes", and this expression is defined in -8- Article 41(9) insofar as living accommodation is provided for an "employee" to mean for "a person employed under a contract of service". The distinction between a "contract of service" and a contract for services, or a contract of employment is well understood in the law of contract, and in the landlord/tenant and master/servant relationship. The relevance of the distinction in rating law was dealt with by Lord Hodson at p 626 in Johnstone's case and by Lord Diplock in his speech in the Commissioner of Valuation v Fermanagh Protestant Board of Education [1970] NI 89, and a contract of service gives rise to a service tenancy which leaves the tenant as the occupier in rating law. So, apportionment under Article 41(3) is required only where one finds use for "domestic purposes" for example the provision of living accommodation for an employee under a contract of tenancy, viz as "a service tenant". This leaves untouched the case where the user is to provide living accommodation for an employee as an integral (as opposed to a collateral) part of the relationship of master and servant. In this case, the obligation to reside was so closely integrated with the obligation to perform the duties contracted for, that there is little if any room for the view that the residential user can be regarded as separate and distinguishable from the user for the purposes for which the hereditament was occupied by the Committee. But in any event, no apportionment is required where the "domestic purposes" are not the provision of living accommodation for "an employee under a contract of service". The hereditament shall be distinguished as exempt under Article 41(2)(c) as occupied by a charity, and under Article 41(2)(d) as occupied by a body not established or conducted for profit and wholly or mainly used for the Committee's charitable main objects. The respondent to pay the appellant's cost of and incidental to the hearing to be taxed on the High Court scale by the Registrar if not agreed. ORDERS ACCORDINGLY 29th October 1982 Sir Frank Harrison Lands Tribunal For Northern Ireland -9- Appearances:Appellant - T T Ferriss, instructed by Messrs Holmes & Swann, Solicitors, Antrim. Respondent - Mrs I E McDowell, instructed by the Crown Solicitor, Belfast. - 10 -