Phonetic squib_Moore Language

advertisement

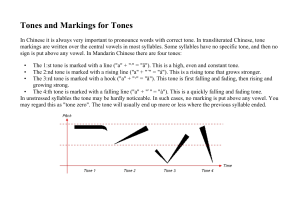

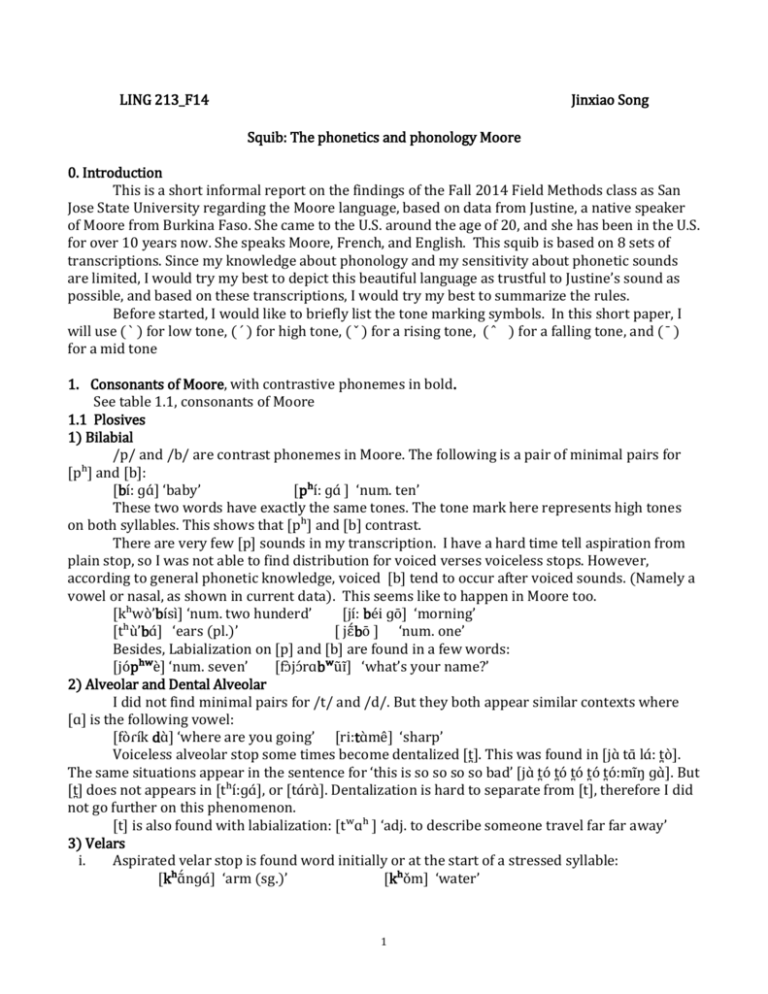

LING 213_F14 Jinxiao Song Squib: The phonetics and phonology Moore 0. Introduction This is a short informal report on the findings of the Fall 2014 Field Methods class as San Jose State University regarding the Moore language, based on data from Justine, a native speaker of Moore from Burkina Faso. She came to the U.S. around the age of 20, and she has been in the U.S. for over 10 years now. She speaks Moore, French, and English. This squib is based on 8 sets of transcriptions. Since my knowledge about phonology and my sensitivity about phonetic sounds are limited, I would try my best to depict this beautiful language as trustful to Justine’s sound as possible, and based on these transcriptions, I would try my best to summarize the rules. Before started, I would like to briefly list the tone marking symbols. In this short paper, I will use ( ̀ ) for low tone, ( ́ ) for high tone, ( ̌ ) for a rising tone, ( ̂ ) for a falling tone, and ( ̄ ) for a mid tone 1. Consonants of Moore, with contrastive phonemes in bold. See table 1.1, consonants of Moore 1.1 Plosives 1) Bilabial /p/ and /b/ are contrast phonemes in Moore. The following is a pair of minimal pairs for [pʰ] and [b]: [bí: ɡɑ́ ] ‘baby’ [pʰí: ɡɑ́ ] ‘num. ten’ These two words have exactly the same tones. The tone mark here represents high tones on both syllables. This shows that [pʰ] and [b] contrast. There are very few [p] sounds in my transcription. I have a hard time tell aspiration from plain stop, so I was not able to find distribution for voiced verses voiceless stops. However, according to general phonetic knowledge, voiced [b] tend to occur after voiced sounds. (Namely a vowel or nasal, as shown in current data). This seems like to happen in Moore too. [kʰwò’bísì] ‘num. two hunderd’ [jí: béi ɡō] ‘morning’ [tʰù’bɑ́ ] ‘ears (pl.)’ [ jɛ́ bō ] ‘num. one’ Besides, Labialization on [p] and [b] are found in a few words: [jópʰʷè] ‘num. seven’ [fɔ̀ jɔ́ rɑbʷũɪ] ‘what’s your name?’ 2) Alveolar and Dental Alveolar I did not find minimal pairs for /t/ and /d/. But they both appear similar contexts where [ɑ] is the following vowel: [fòɾík dɑ̀ ] ‘where are you going’ [ri:tɑ̀ mê] ‘sharp’ Voiceless alveolar stop some times become dentalized [t̪]. This was found in [jɑ̀ tɑ̄ lɑ́ : t̪ò]. The same situations appear in the sentence for ‘this is so so so so bad’ [jɑ̀ t̪ó t̪ó t̪ó t̪ó t̪ó:mĩŋ ɡɑ̀ ]. But [t̪] does not appears in [tʰí:ɡɑ́ ], or [tɑ́ rɑ̀ ]. Dentalization is hard to separate from [t], therefore I did not go further on this phenomenon. [t] is also found with labialization: [tʷɑʰ ] ‘adj. to describe someone travel far far away’ 3) Velars i. Aspirated velar stop is found word initially or at the start of a stressed syllable: [kʰɑ́ nɡɑ́ ] ‘arm (sg.)’ [kʰǒm] ‘water’ 1 [zɑ̀ ’kʰɑ́ ] ‘house’ [kʰɑ̀ :ɾ’ní:nɑ̀ ] ‘foot’ ii. /ɡ/ and /k/ [ɡ] and [k] are clearly different from each other. They appear in similar syllables in [kʰôɾòŋɡó] ‘school’. Other examples are: [fò’ɾík dɑ̀ ] ‘where are you going’ [bí: ɡɑ́ ] ‘baby’ [ɡʲé nɡàʰ] ‘crazy’ Aspirated [kʰ] is found in many words. Palatalization and aspiration can exist simultaneously. [kʰìnɡáʰ] ‘blue’ [kʲʰē :mɑ́ ʰ] ‘my sibling (sg)’ Palatalization also exists on [ɡ], besides, [ɡ] here is found varying with [dʒʲ] once in: [ɡʲé nɡà] or [dʒʲé nɡà] ] ‘crazy’ Labialization along with aspiration is found on [kʰʲ]: [kʰʷɛ̄ nɡɑ̀ ] ‘empty’ iii. Voiced Velar stop is in free variation with voiced velar fricative. [ɹʷò:ɣɑʰ] and [ɹʷò:ɡɑʰ] both means ‘room’. [wè:ɣo] and [wè:ɡo] both means ‘forest/to cultivate’. 4) Uvulars: Voiced uvular stops [q] and [ɢ] are in free variation with Uvular fricatives [χ] and [ʁ] [nũwɔqɔdu] ‘ long arms’ [wɔʁo] ‘long’ [toqodɑ] and [toχodɑ] both means ‘travelling’ [fo tʰɑ:ɾɑ jum boʁo] ‘How old are you?’ sounds like [boɡo] at the end 1.2 Fricatives: Besides the free variation between fricatives with stops in different manners, namely velar and uvular, there are some evidences for the exsistence alveolar fricatives and labial fricatives. 1) /s/ and /z/ [sífù] ‘ribs/bee’ [nífù] ‘one eye’ These two sounds have the same tone, they contrast with each other in terms of consonants. [zí:mɑ̄ ] ‘fish’ [kʰwò’bísdɑ̀ ] ‘num. 300’ 2) /f/, /v/ and [β], [ɸ]. They occur in variation with bilabial fricatives [β] and [ɸ]. Justine’s upper teeth sometimes barely touch her lower lip. But these two manners (bilabial and labial dental) do not contrast. They should belong to the same phoneme. [bíɾīfú] ‘adj. small’ [fò] ‘PRON. you’ 1.3 Nasals /m/, /n/, /ɲ/, and [ŋ] I found that [m] occurs mostly before [e] and [ɑ], it never occurs before high vowels. [n] occurs widely unconditioned. [ɲ] occurs in only a few words, all in word-initial position, and the vowel immediately after it is nasalized. [ɲiɑndē] ‘teeth’ [ɲɔ́ :ɡɑ̀ ] ‘chest’ [nífù] ‘one eye’ [nù mɑ́ ] ‘short greeting’ [mɑm] ‘I’ [nɑ́ :sè] ‘num. four’ [ŋ] occurs before velar stops, it’s generated through assimilation [tĩŋɡɑ] ‘dirt’ [kʰôɾòŋɡó] ‘school’ 1.4 Approximants. [w] and [j] [w] and [ j ] both occurs in Moore. [j] is found in the question word [jɛ̀ ], [w] is found mostly in word beginning. For example, [wɑ́ :fɑ̄ ] ‘snake’. 2 [j] is found labialized in the word for ‘bird’ : [jʷé:lɑ́ ] 1.5 /r/, /ɾ/, /ɹ/ and [l] Among these sounds, trill is the most obvious one to observe. But trill sometimes goes into a tap in word-middle. There are also several evidence showing a difference between velarized lateral and alveolar approximant, I listed some words here, but I was not able to find the distribution rule of these sounds. [ɹò:ɣɑʰ] ‘room’ [ɹɔ̀ :ɡó] ‘stick’ [ʌm jɑ́ : brɑ̀ mbɑ̄ ] ‘my grandpartents (pl)’ [ʌm kʲʰẽbiɾiblɑʰ] or [ʌm kʲʰẽbiɫiblɑʰ] ‘my younger sister’ 2. Vowels of Moore: 2.1 Vowel inventory: See table 2, vowels of Moore, with contrastive phonemes in bold 2.2 Contrast vowels: 1) /ɑ/, /o/, /i/ and [ʌ] , [ɐ] [kʰɑm] ‘oil/butter’ [kʰǒm] ‘water’ [nífù] ‘nose’ [nɑ́ fù] ‘cow’ These two pairs of sounds have the same tones, they contrast with each other in terms of vowels. [ɑ] is found centralized and higher as [ʌ]and[ɐ]sometimes, but its hard to distinguish. Aspiration is found with [ɑ] at the end of a word. For example: [kʰìnɡáʰ] ‘blue’ [mmɑ bɑ́ : bɑʰ] ‘my father’ 2) /u/ and /o/ [kʰūkʰúɾì] ‘pig’ [kʰókʰóɾe] ‘neck’ This pair of sound is very similar to each other. /u/ and /o/ appear in the same conditions. Therefore they should be contrastive sounds. 3) /ɔ/ and /o/ Often times these two sounds are similar. For example, I found it difficult to distinguish /fɔ/ and /fo/ for the pronoun ‘you’. Since we do not fine minimal pairs, its not correct to say these are contrast phonemes. However, they do occur in the same context in the following two words: [ɲõ: ʁɑ̂ mè] ‘burn’ [ɲɔ́ :ɡɑ̀ ] ‘chest’ 4) /ɛ/ and /e/ and /i/ These are different phonemes since they are found in near minimal pairs: [kʰūkʰúɾi] ‘pig’ [kʰókʰóɾe] ‘neck’ ̀ ̄ [kʰinɡáʰ] ‘blue’ [kʲʰe:mɑ́ ʰ] ‘my sibling (sg)’ The difference between [e] and [i] is difficult to observe. Often times when it occurs in word final, [e] will sounds like [i]. The same problem also happens between [e] and [ɛ]: [né ji: béi ɡó] ‘good morning’ [fo ’zɑ́ kʰɑ̀ ʰ bê: jɛ̀ ?] ‘Where is your house? (where do you live )’ [soɾi] or [soɾe] ‘road’ 5) Vowel harmony As is shown in the contrast between /u/ and /o/ above, there is a vowel harmony in terms of highness. High vowels occur with high vowels, and mid vowels are found more often together with mid vowels. The following examples show [u] occurs with [i], and [e] occurs with [o]. 3 [kʰūkʰúɾì] ‘pig’ [kʰókʰóɾe] ‘neck’ [bíɾīfú] ‘small’ [weɣo] ‘forest/to cultivate’ However, this rule does not take place on words that has low vowel [ɑ]. For example: [nɑ́ fù] ‘cow’ [fò’ɾík dɑ̀ ] ‘where are you going’ 3. Syllable structure: Syllables are mostly CV in this structure, and nasalized V occurs frequently. Nasalized consonant is found on [w] in some words. CV can be reduplicated in the form of CVCV. CCV occurs in the word for ‘my’, and also in the form of secondary articulation, its still an arguable case to transcribe [ɹʷ], [pʷ], [kʷᶨ] as multiple consonants. 1) CV (CṼ) and the reduplication of CV (CṼ). [nî:] ‘number ‘eight’ [soɾi] ‘road’ [toqodɑ] ‘travelling’ 2) CṼ and C̃ Ṽ [wũn toɡo] ‘day time’ [mwé ] ‘rice’ [nũwɔqɔdu] ‘arms’ [kʰwò’bísdɑ̀ ] ‘num. 300’ 3) CCV [mɑ́ sɡɑ̀ ʰ] ‘cold’ [mmɑʰ] ‘my’ [kʰʷɛ̄ nɡɑ̀ ʰ] ‘empty’ 4. Super segmental This section includes nasalization, tone, stress and long vowel. 4.1 Nasalization Nasalized vowel can spread onto a preceding glide. As in [wũn toɡo] ‘day time’. Nasalized vowel can also appear isolated. Some vowels can be nasalized vowel by themselves, as in [jɛ́ bō] ‘ num. one’, [ɲiɑde] ‘teeth (sg.)’ Some vowels are nasalized because of assimilation with the following vowels, as in [bìnsrī] ‘sand’. Vowels are also found nasalized after nasal stops, as in [ʌm tɑ:ɾɑ jõ:ŋ pʰɡɑʰ] ‘I am ten (years’ old)’ 4.2 Tones The data exhibit seven different level tones, including ( ̀ ) for low tone, ( ́ ) for high tone, ( ̌ ) for a rising tone, ( ̂ ) for a falling tone, and ( ̄ ) for a mid tone. I choose to put a rising tone when there is a high tone followed by an extra high tone, as in the word for water: [kʰǒm]. Initially I marked it as [kʰóm̋], however, it sounds just as the same as a rising tone in Chinese. For example, the word for ‘field’ [tʰiɑ̌ n] has a rising tone similar with the word for water in Moore. In the following section, I will put more rising and falling tones. The rising tone indicate the tone of the consonant preceding the vowel is lower then the vowel, the falling tone indicate the consonant preceding the vowels is higher 1) Tone exists in Moore There are evidences that proves this language to have tones: [kʰôɾòŋɡó] ‘school’ [kʰòlóŋɡò] ‘uneducated’ [wɑ̄ :fɑ̄ kʲè mɑ̌ m] ‘snake bite me’ [wṹn tʰó kʲé mɑ̀ m] ‘I am good’ I have also found some more rising and falling tones: [nî:] ‘number ‘eight’ [wě ] ‘number ‘nine’ [vî:] live ( in ‘fo vi jɛ?’, ‘where do you live’) [bê:] live (in ‘fo zɑka be jɛ?’ ‘where your house is’) 2) Tone alternation 4 Though there is not enough evidence to prove what exactly are the contrastive tones in Moore. The tone is definitely changing. In the first four pairs, when Justine pronounced the word on the left column alone, the first syllable is low tone, but when it occurs after another word, which are ‘my’ and ‘its’ in the following examples, the first syllable changes to a high tone. If it is a high tone when it stands alone, then it doesn’t undergo this change. [kʰɑ̀ :ɾ’ní:nɑ̀ ] ‘foot’ [mɑ̀ m ’kʰɑ́ :ɾnî:nɑ̀ ] ‘my foot’ [zɑ̀ ’kʰɑ́ h] ‘house’ [fo ’zɑ́ kʰɑ̀ h bê: jɛ̀ ?] ‘Where is your house? (where do you live )’ [tʰù’bɑ́ ] ‘ear (pl)’ [mɑ̀ m ’tʰúbɑ́ ] ‘my ears’ [nò’ɣó] ‘sweet’ [jɑ ’nóɣó] ‘its sweet’ [’kʰɑ́ :rɡɑ́ ] ‘leg’ [mɑ̀ m kʰɑ́ :rɡɑ́ ] ‘my leg’ [’rṍŋdí] ‘knee [mɑ̀ m rṍŋdí] ‘my knee’ Besides, a high tone changes to falling tone/low tone when following a high tone. Examples are in ‘foot’ vs. ‘my foot’, and ‘house’ vs. ‘where is your house?’. I think the change from [kʰɑ̀ ] to [kʰɑ́ ] trigger the change of [ní:] to [nî]. Similarly, [zɑ̀ ’kʰɑ́ h] changes to [zɑ́ kʰɑ̀ h] when following ‘fo’. This also occurs in numbers, [jì: bú] change to [jí: bù] following ‘lɑ’: [jì: bú] ‘2’ [pʰí:sī lɑ̀ jí: bù] ‘22’. However, this rule does not apply to verbs, for example, in [fò vî: jɛ̀ ] ‘where do you live?’, [vî:], which is the verb for ‘live’ does not participate in tone change. 4.3 Stress Stress shift occurs along with tone change. There is not enough data to show whether stress shift caused tone change, or tone change triggered stress shift. But in the examples in ‘tone alternation’ in (4.2-(2)), stress changes along with high tone. 4.4 Long vowel All vowels are discovered to have long vowel, but the most obvious one is found on front vowel [i], [e]. Further research still needed on this. [wi:̄ n dɡɑ̀ ] ‘mid-day’ [pʰí:sì] ‘number 20’ [fo’zɑ́ kʰɑ̀ h bê: jɛ̀ ?] ‘Where is your house? (where do you live )’ 5. Conclusion This short informal paper comes from four week’s transcription on Moore language. Due to limited phonology knowledge and a still ‘improving’ sense of unfamiliar sounds, details of phonetic properties and sound distributions still need further investigation. 5