A subject/object asymmetry in the acquisition of DPs

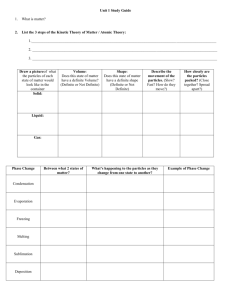

advertisement

THE ROMANCE TURN: WORKSHOP ON THE ACQUISITION OF ROMANCE. SEPT. 16-18 2004, MADRID A subject/object asymmetry in the acquisition of DPs in Catalan and English Ana T. Pérez-Leroux, University of Toronto, at.perez.leroux@utoronto.ca Thomas Roeper, University of Massachusetts, roeper@linguist.umass.edu Anna Gavarró, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, anna.gavarro@uab.es 0. Introduction Some crosslinguistic difference in the semantic mapping of nominals: Definite/Bare noun contrasts are general in English but exhibit a subject asymmetry in Catalan (and other Romance Languages). (1) Subjects Objects English Tigers live in India (Gen) The tigers live in India (Spec) I want shoes. (Gen) I want the shoes. (Spec) Catalan/Spanish *Tigres viuen a Àfrica Els tigres viuen a Àfrica (Gen/Spec) Busco sabates. (Gen) Busco les sabates. (Spec) General questions: How do children acquire the semantic distribution of different nominal projections? How do they treat parametric variation in nominal reference? Are some configurations/languages easier than others? Goal: to compare the relative rates of development for how children acquire the contrast between definite and bare nouns (BNs) in Catalan and English. Parametric advantage hypothesis: Chierchia’s (1998) Nominal Mapping Parameter (NMP) predicts that typologically simple languages (where nominal projections are uniformly mapped into a semantic type) should be acquired earlier than mixed languages, where nominals map both as entities <e> and predicates <e,t>. Syntactic competition hypothesis: Semantic mapping is decided, not as global parameters, but locally, in terms of competition of forms for the same syntactic environment. Definite objects in Catalan, where BNs can occur, have the same semantics as definite subjects English (Gavarró et al 2003, GALA). Development should be comparable rates in contexts where the bare/definite alternation shows the same semantics across languages. 1. Nominal mappings across languages 1.1 Parametrized approaches to nominal reference Competing views on nominal reference: I. The syntax-semantics map is universally fixed and, as a consequence, D must always be projected for argumenthood (Longobardi 1996) II. Languages vary at the syntax-semantics interface (Chierchia 1998) Canonical view of the operation of the syntax-semantics interface: 1. Syntactic categories are mapped onto semantic types (determining denotation) a. DP <e> referential nominals, or Generalized Quantifiers [arg] b. NP NP <e,t> [pred] 2. LFs are compositionally interpreted using a small set of universal rules 3. Local type mismatches are resolved through a highly constrained set of universally available type shifting operations. Chierchia 1998 Nouns have a double nature: a) they play the part of restrictors to quantifiers, and thus look like predicates; or b) as names of individuals or names of kinds. In this respect, they are argumental. C. proposes crosslinguistic variation on to what is the basic mapping, a) or b). Nominal Mapping Parameter: nominal projections can be directly mapped as semantic arguments (±arg) (capable of referring to entities directly) or as semantic predicates (±pred) (requiring a det/quantifier to be capable of referring) Predicted order of acquisition based on subset principle & NMP (2) Chinese pattern>Romance pattern > Germanic pattern (Chierchia 1998: 400) Justification: Children start by treating every N as mass, then learning the existence of count/mass distinction and articles, but restrict the distribution of bare nouns, finally learn that bare arguments are freely allowed, although lexically conditioned. Language typology according to NMP I. NP [+arg, -pred] languages (like Chinese) i. Generalized bare arguments ii. the extension of all nouns is mass iii. No Pl iv. Generalized classifier system II. NP [+arg, +pred] languages (Germanic) i. Mass nouns will occur as bare arguments; (singular) count nouns won’t. ii. have mass/count distinction: +arg mass +pred pred iii. have number distinction iv. Free use of ‘’ is allowed by the category– type mapping. But it is defined (it yields kinds) only for plurals; as a consequence plurals will be able to occur as arguments. III. NP [-arg, +pred] languages i. No bare nouns in argument position ii. Have mass/count distinction iii. have number iv. may or may not have null determiner []. But may only appear in positions that license empty elements (i.e, proximity to a lexical head (DO and objects of preposition) Type shifting: A variety of operations or functional elements are able to shift semantic type ( iota , intentional up , DKP, , etc.). T-s operates freely as long as there is not a D whose semantic function is identical to it. 1.2 Semantic competition of elements in the functional domain The existence & interpretation of bare nouns in a language depends on the existing lexical options in the language. (Chierchia 1998, Dayal 2002) (3) a. Dogs are common. b. Gold is rare. c. *Dog is common. d. #The dogs are common. I. Why are singular mass allowed in English? direct map as <e> Mass/count distinction is lexical: change vs. coins have the same denotation but behave differently. II. Why are bare plurals possible? Count nouns are type <e,t>. It can be shifted up to a kind interpretation by the free type-shifting operator up (). III. When can these typeshifting devices apply? Only in a restricted manner. ‘Language-particular choices win over universal tendencies (‘elsewhere condition’), and ‘don’t do covertly what you can do overtly’ (if the language has alternative means of expressing something). Blocking principle: type shifting as last resort: block a type-shifter if the language contains a Determiner with the same value as the type-shifter IV. Why are singulars count nouns ungrammatical? The typeshifter up () applied to a singular count noun will not yield a proper kind (dog), because the dog-kind includes the set of dogs, not an atom from that set. Kinds are functions from world into pluralities, which are the sum of [typical] instances of the kind (p.349). V. Why are definite plurals not generic in English (given they exists elsewhere)? Basic map of the definite is iota. But English allows the use of the typeshifter , which could provide it with kind reference. Not applicable here because the bare argument bleeds its use in generic meanings. VI. Why does Romance disallows bare nouns in subject position? Romance nouns are <e,t>, NPs can only be arguments if D is projected. R Languages that have bare noun do so exceptionally (in positions that license empty categories such as DO and object of P). BNs are excluded from subject position (4) a. b. *Dinosaures es van extingir. dinausaurs refl past-pl extinct *Tigres són mamífers. tigers are mammals A bare noun patate will have the following analysis, with is a null D head, which has the same semantic contribution as the typeshifter (). (5) [DP [NP patate ] VII. Why does Romance allow definite plurals to have generic readings? To make up for its absence of bare nouns in argument position. (6) a. b. Los dinosaures es van extingir. (def. counterparts to (4) Els tigres són mamífers. The nominalizer is an intentionalized version of : “It follows that in appropriate (intensional) contents we will be able to obtain with (i.e. = the definite determiner) what we can get in English with (i.e. BNs). The relevant contexts are two: generic sentences and sentences with kind-level predicates.” (Chierchia 1996, 392) VIII. Why there is no blocking effect between Romance definite and ? and the definite do not have identical meanings, just meanings capable of overlapping in one domain. Hence, use of as meaning for null D is unaffected by the definite. 1.3 Syntactically local competition Problems with the NMP approach: •blocking approach applies to def plural as kinds but not to def sing kinds •The distribution of kind readings for nominal classes in one domain (objects in Romance) matches exactly that of the other language type (objects and subjects in English) but the explanatory mechanisms are radically different. (7) a. b. Busco sabates. look-for-1s shoes ‘I look for shoes (generic).’ Busco les sabates. look-for-1s the shoes ‘I look for the shoes (specific).’ •Furthermore, the lexical restrictions (count/mass) are identical, but again have different sources. (8) a. *Busco sabata. look-for-1s shoe b. Busco farina. look-for-1s flour Under NMP Bare objects (7a) and (8b) are possible by virtue of the null D Mass/count contrasts (8a-b) parallels (3b-c). Mass is possible in English by lexical reasons, but in Catalan thanks to a type-shifting null determiner. Subject/object asymmetry in Romance receives two explanations, one syntactic (ECP regulated distribution of ), and one semantic (definites, which are mapped as are allowed to intentionalize (become kind-referring), in appropriate semantic contexts (ILPs & as subjects of generic sentences). Our proposal: This mapping contrast (BN generic, Defspecific) works across languages that illustrate different parametric options, such as Catalan and English. The semantic behavior of the structural contrast is the same in those positions where the contrast exists (i.e., where BNs/definites contrast). •Blocking principle regulates the alternation locally (at the syntactic level) rather than macro-parametrically (at the language level) 2. The development of nominal mapping 2.1 Evidence for crosslinguistic variation in the emergence of D: data from corpus studies • definite articles cease to be omitted earlier in French and Italian than in English and Swedish (Chierchia, Guasti & Gualmini 1999), and earlier in Catalan than in Dutch (Guasti, de Lange & Gavarró 2004). While phonological factors may play a role in boosting article production in Romance, despite phonological differences Romance articles are produced as in the target earlier than in Germanic (Lleo & Demuth 199?) •Marinis 2002: early & extensive use of determiners in child Greek •Kupisch 2003: evidence of different acquisition rates in bilingual children. Overall differences is consistent with NMP, showing an advantage in emergence of D in Romance, but, given that these results come from overall use, they are not direct evidence about the nature of the semantic mappings. Experimental testing is needed to substantiate if the semantic mapping is indeed as in the target when syntactic production is adult-like. 2.2 Evidence of knowledge of semantic mapping of nominals •Sensitivity to bare/DP contrasts: Burns and Soja (1997): Children are sensitive to the idiomatic features of the bare noun construction: (9) a. She is at church. (Institutional reading) b. She is at a church (Location reading) 4 year olds demonstrated substantial discrimination, selecting determiners 20% for institutional scenario versus 75% for location scenario. Pérez-Leroux & Roeper (1999): Young children knew the locality properties of bare nominal idioms in contrast with DPs: (10) a. Everyone went his/Ø home? (bound 75-100% in BN, ~25% in poss) b. Everybody hoped the Lion King would go home/to his home, and he did. (Non-local interpretation ~10% in BN, ~40% in poss) 2.3 Overextension of definites •Knowledge of the definite/indefinite distinction: Young children attend to preceding linguistic context and to supply the correct determiner in a second mention of an NP (Maratsos 1976, Karmiloff-Smith 1979, Schafer and deVilliers 1999) (11) a. b. Bill bought a cat and a dog, (specific) but the children only liked the dog Bill wanted a cat and a dog, (non-specific) but he couldn't find a dog he really liked •But also overuse of the definite in contexts that do not meet the uniqueness requirement. (Maratsos 1976; Karmiloff-Smith 1979; Schaeffer &Matthewson 2000, Matthewson, Bryant and Roeper 2000; Schafer & deVilliers 1999) (12) The boy plays baseball with a bat, and a ball. (on target) 3 ducks and a dog crossed the bridge. A duck fell down. substantial differences. (Schafer and deVilliers 1999) •Overgeneralization of definites to inalienable contrast (13) She just touched the/her nose. [30% inalienable] (Ramos 1999) (14) De drie jongetjes raakten de neus aan. The three boys touched the nose. [Only 30% rejection inalienable] (Baauw 2000) (15) Suzy put the leg/her on the table [25% inalienable in 4 year olds] (Pérez-Leroux, Munn & Schmitt 2003) 2.4 Overextension of definites in generic contexts Gelman & Raman (2003): Picture of a short-necked giraffe: (16) Now, I am going to ask you a question about the giraffes/giraffes. Do Giraffes/the giraffes have long necks? [Gen response: 10% error to definites, 63-80% correct to BNs] Reliable discrimination for bare/definite NPs. However, an overall bias against generic, as the experiment had a) high proportion of ‘other’ responses (20-25%), and b) included artifactual kinds (cars) and c) incidental as opposed to characterizing properties (such as color). Pérez-Leroux, Munn & Schmitt (2003, in preparation): Figure 1: Stories testing generic interpretation in definite/BNs as subjects Zippy the zebra and Suzy the zebra are spotted. The giraffe wonders why they look different. Now let me ask you some questions… Prompt: Do the/Ø zebras have spots? Table 1. Generic responses to definite plurals subjects (Pérez-Leroux et al 2003) English (BNs vs. definites) Spanish (Ambiguous Romance definites vs. demonstratives) • discriminate BNs and definites •Strong generic response to definites •high rates of correct response to BNs •Good development with demonstratives. •high rates of def. generic errors Table 2.The effect of tense on generic readings (Pérez-Leroux et al 2003) English •No effect of tense in English children. •Less generic error to definites than in Exp. 1, due to modification in stories (names for atypical characters were eliminated) and prompt (after Gelman & Raman 2003) Spanish • past tense restricted the availability of generic interpretation, but some errors persist. Summary: some evidence of generic errors with plural definites, but results that vary with subtle methodological manipulations. Def. generic error in English does not seem to be developmentally resolved. Evidence compatible w/NMP. 2.5 Overall conclusions about mappings •different rates of emergence of D that correspond roughly to the typology in the NMP •Evidence that the mapping of English definite as the iota operator not complete •evidence that the English/Dutch generalize their definites to inalienable construal (as in Romance) •evidence that English may have a generic error with plural definite 3. Study Methods and Participants •Goals: to compare development of definites in objects, where t •Subjects were read 4 short stories. Two characters, one who needed something specific (e.g., little girl looking for her cinderella’s glass slippers) and another with a general need (barefoot girl who needs shoes). Figure 2: Sample story & questions testing definite/BN objects …there is a little girl who wants to dress up as Cinderella and needs special shoes for that (point to little girl, princess-like). Her older sister (point to taller, barefoot girl) helped her look for them in the trunk, and finds them. •Definite and BN objects were counterbalanced over target questions. (15) a. Qui necessita les sabates? Who needs the shoes? b. Qui necessita sabates? Who needs shoes? Specific answer: little Cinderella Generic answer: older sister •Inclusive answer to generic: both girls Catalan adult speakers are equally divided between a) those whoallow generic answer only (1/3) b) those who consistently allow inclusive answers (1/3), and those who allow inclusive answer sporadically (1/3). Informal judgments, Carlson (pc), suggest the same is true for English We treat patterns as convergent if they include specific answer to BNs but definites were not given a generic answer. 4. Results 4.1 Catalan Results Participants groups: I-Younger: (N=11, 2;7–3;9, M=3;4); II-Middle: (N=11. 3;11-4;9, M=4;4); III-Older: (N=12, 4;10–5;10, M=5;3); IV-Adults: (N=10). Figure 3: Proportion of generic answers per determiner in Catalan. *age F 3,40=3.252, p=.0316 Interaction Bar Plot for Determiner Effect: Category for Determiner * Age groups Row exclusion: gavarro.txt (imported) 1.2 Cell Mean 1 I .8 **determiner F 1,40=55.572, p<.0001 II .6 III IV-adults .4 **determiner x age F 3,40= 13.712, p<.0001 .2 0 Def inite Bare Cell 4.2 Preliminary English Results Participant groups: I-Younger: (N=10, 2;9–3;11, M=3;4); II-Middle (N=9, 4;0-4;11, M=4;6); III- Older children (N=3, 5;4–5;11, M=5;8) Figure 4: Proportion of generic responses per determiner in English n.s. age F 2,19= 1.172, p=.03312 n.s. determiner F 2,19=.981, p=.3343 n.s. determiner x age F 1,19=1.176, p=.5653 4.3 Individual performance De f BN 1 0 1 .5 1 1 .5 .5 .5 0 .5 1 0 0 B. Target Conver gent A. Not targetconvergent Table 3. Catalan-speaking children (N=34). Figures on the left represent the proportion of generic answers to definite and bare nouns. Figures on the right represent number of children per age group falling into the various patterns. Light area: target convergent patterns. Shaded area: patterns that are not target convergent. 0 .5 0 1 Total number group Characterization A1. Definite generic error A2. Definite generic error A3. Same responses to both A4. Same responses to both A5. Some definite generic error A6. Some definite generic error B1. All specific responses B2. Near target B3. Target of participants per Grou p I 3’s Group II 4 ‘s Grou p III 5’s Adul ts 1 0 0 0 4 1 0 0 2 3 0 0 0 3 0 0 4 1 0 0 3 1 0 0 1 3 3 4 5 0 0 10 11 11 12 10 • The 3 year old group has 1 child in the near target pattern, three children giving only specific responses. The 4 year olds have 4/11 children in the near target/target pattern. •Older children have only convergent patterns, answering gen w/ BNs only. • all specific answers is an indeterminate patter. Possibly:result of nodiscrimination, or of children who are sensitive to the BN, but choosing the specific response as part of an inclusive interpretation of the generic. De f BN 1 0 1 .5 1 .5 1 .5 .5 0 .5 1 0 0 B.Con vergen t A. Not targetconvergent Table 3. Individual response patterns for the English children. Light area: target convergent patterns. Shaded area: patterns that are not target convergent. 0 .5 0 1 Total number per group Characterization A1. Definite generic error A2. Definite generic error A3. Same responses to both A4. Same responses to both A5. Some definite generic error A6. Some definite generic error B1. All specific responses B2. Near target B3. Target of participants Group I 3’s Group II 4 ‘s Group III 5’s 1 1 1 1 1 3 5 3 3 3 2 10 9 5 •overall, the same developmental patterns than in Catalan, where children in the non-convergent patterns are few, and are not present in the older group. •However, the data shows no children on target, suggesting Englishspeaking children are delayed in comparison to Catalan-speaking children. 4.4 Across-Language Comparison Figure 4:Across language comparisons per age groups Interaction Bar Plot for prop correct Effect: Category for prop correct * Language Split By: agegroups Cell: I Row exclusion: barenounComp 1 Cell Mean .8 .6 Catalan English .4 3 year olds •Small advantage in the performance of English children (can be attributed to small age difference in the two groups) •Near significant effect of language (p=.0547) .2 0 Barecorr Def corr Cell 4 year olds Interaction Bar Plot for prop correct Effect: Category for prop correct * Language Split By: agegroups Cell: II Row exclusion: barenounComp 1 Cell Mean .8 .6 Catalan •English children lag in BN Non-significant effect of Language (p=.2755) •No difference with definites. English .4 .2 0 Barecorr Def corr Cell Interaction Bar Plot for prop correct Effect: Category for prop correct * Language Split By: agegroups Cell: III Row exclusion: barenounComp 1 Cell Mean .8 .6 Catalan English .4 .2 0 Barecorr Def corr Cell 5 year olds •English children lag in BN •Significant effect of language (p=.0350) and language x determiner interaction (p=.0350). •No difference with definites. •Sample size of English 5 yearold group (N=3) not robust enough to yield a valid comparison. The data shows no evidence for Romance advantage in the contrast 5. Discussion •Our results: No particular Romance advantage w/ object contrasts •children’s acquisition of variation in semantic mapping is subordinate to syntactic structure (objects/subjects) •asymmetry may be part of UG: generic interpretation of definite singular is not available for objects either (16) Everyone hates the lion The lion is hated by everyone • Catalan-speaking children are not tempted to overgeneralize the generic interpretation of definites from subject to object position •English children, although having shown evidence of definite overgeneralization in subject position, do not show such evidence in object position. •Parametric system is to a certain extent misleading. Data (descriptive and experimental) supports the view of nested parametric values within languages (Roeper 1999). Decision about D system are not made across the board •Results support a view of syntactically local blocking effects as an entry into the parametrized variation in nominal mappings. Selected References Baauw, Sergio. 2000. Grammatical features and the acquisition of reference. Univ. of Utrecht, Ph.D. Dissertation. Chierchia, G., T. Guasti & A. Gualmini (1999) ‘Nouns and articles in child grammar and the syntax/semantics map’. Paper presented at GALA, Potsdam. Chierchia, Gennaro. 1998. Reference to kinds across languages. Natural Language Semantics 6:339-405. Dayal, Veneeta. 2002. Number marking and (in)definiteness in kind terms. Ms., University of Rutgers. Guasti, Maria Teresa & Anna Gavarró. 2003. Catalan as a test for hypothesis concerning article omission. BUCLD 27(pp.288-298). Somerville, Cascadilla Press. Guasti, T., J. de Lange & A. Gavarró (2004) ‘Article omission: across child languages and across special registers’, in van Kampen, J., & S. Baauw (eds.) Proceedings of GALA 2003, LOT Occasional Series, vol. 1. Hollander, Michelle A; Gelman, Susan A; Star, Jon. 2002. Children's interpretation of generic noun phrases. Developmental Psychology 38 (6), 883–894. Marinis, Theo 2002, in press. Minimal inquiries and the acquisition of the definite article in Modern Greek. Proceedings of the 34th Colloquium in Linguistics. Peter Lang Verlag Matthewson, Lisa, Tim Bryant and Tom Roeper. 2001. “A Salish Stage in the Acquisition of English Determiners: Unfamiliar “Definites”. Proceedings of SULA: The Semantics of Under-Represented Languages in the Americas. University of Massachusetts Occasional Papers in Linguistics 25. Pérez-Leroux, A. T., and T. Roeper.1999. Scope and the structure of bare nominals: evidence from child language. Linguistics 37, 927-960. Pérez-Leroux, A.T., C. Schmitt and A. Munn. (2003). The development of inalienable possession in English and Spanish. in Going Romance 2002, ed. by R. Bok-Beenema, A. Van Hout and B. Hollebrandse. Amsterdam, John Benjamins. Pérez-Leroux, A.T., C. Schmitt and A. Munn. (2003). ‘Of spotted zebras and vegetarian tigers: The acquisition of determiners and the syntax/semantics interface”.