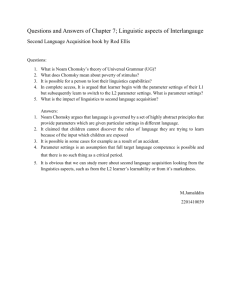

Lecture 13

advertisement

BMN ANGD A2 Linguistic Theory Lecture 13: Language Acquisition 2 Theories of Language Acquisition 1 Introduction There are very few ancient theories of language acquisition per se. Probably it is such a natural fact about humans that it didn’t come across as anything worth questioning. The Greeks did debate over whether words were in language were a natural ‘god-given’ aspect of the bits of the universe they refer to or whether they were invented by man, ultimately giving rise to the rationalist/empiricist divide on the question of the origin of knowledge, and one might speculate as to whether these points of view led ancient philosophers to the claim that language was given to children by the gods, or invented by them as they went through the procedure. But to my knowledge, the question was never really put in these terms. Certainly with ancient grammar mainly focussing on word meanings and morphological properties of words, the problem of learning complex syntactic systems was not considered and we had to wait until the early 20th century before syntax became seen to be a central part of grammatical investigation and it was recognised that there was a complex system that would have to be acquired. Even then, however, theories of language acquisition tended to down play the problem and so were entirely inadequate in accounting for the fact that children can and do do it. For example, Bloomfield (1933), influenced as he was by Behaviourist Psychology, put forward the following proposal as to how language acquisition works. Children make noises from birth. Some of these noises approximate language noises of the child’s parents. Whenever the child produces such noises he or she is rewarded by parental attention (aaah! she just said mama!), which reinforces the behaviour of producing that sound. In this way, appropriate languages sounds become more likely to be part of a child’s output and nonappropriate sound production decreases, until such a time that the only sounds that a child makes are those of the parents’ language. While this theory does make use of some real aspects of language acquisition, such as the fact that children do babble, it is clearly totally inadequate to account for even the simplest observations concerning what children actually do. We saw last week that children acquire an abstract grammar not sentences (nor indeed reinforced linguistic behaviour) and it is clear that such a system could not possibly be learned by the proposed method. It requires the child to come out with all the relevant constructions in the first place, so that these can be reinforced by the parents, and the chance that this could happen accidentally are so close to zero as to be not worth considering. Thus the child would already have to possess the linguistic system that they were supposed to be learning in order to be able to learn it! Nearly 25 years later, the Behaviourist B.F. Skinner published another account of language acquisition (Skinner 1957), making use of a more sophisticated model of language, which we will not go into the details of. More important is the fact that two years later Chomsky published a highly critical review of Skinners work (Chomsky 1959), pointing out that it still suffered from the same problems facing Bloomfield’s simplistic theory, though heavily disguised in what Chomsky saw as pseudo scientific notions and terminology. The subsequent fall of Behaviourism and the popularity of Chomsky’s Syntactic Structures (1957) virtually left Chomsky unchallenged in his rationalist approach to language and language acquisition. Mark Newson 2 The Innateness Hypothesis – early years Of course Chomsky’s approach to language acquisition is the rationalist one: the child is born with something which specifically functions to acquire language. It seems hard to avoid this conclusion given the facts of languages acquisition: the difficulty of the task and the ease with which it is carried out. However, although Chomsky had defeated the strong empiricist ‘tabula rasa’ approach, and had argued convincingly in favour of an innatist position, he did not at the time put forward any particular theory. His view was that the theory of language acquisition that was most likely to succeed would be based on a successful theory of language, which was naturally the primary objective of linguistics. Thus while Chomsky argued that an account of language acquisition without reference to some in built mechanism, which he strongly believed would have to be directly related to language, and not just some general ability to learn, he was not really in a position to say just what that mechanism was. Thus, the first attempts to provide a theory of language acquisition along Chomskyan lines were based on a rather vague notion of some kind of Language Acquisition Device (LAD) that the child came equipped with. As transformational grammar developed, and especially as the mathematical linguistics became better understood, it was suggested that what the LAD did was to order possible grammars to provide the learner with not only a set of hypotheses to be tested against the linguistic data presented, but also a set path through this set of languages, so that once a grammar was rejected, the learner would adopt the next hypothesis determined by the LAD. Thus the model of acquisition that followed these ideas was as in (1): (1) data → LAD → learned grammar In this way, we can see how this theory at least attempts to address the fundamental problem of language acquisition: how is it that the child is able to construct an abstract grammar when what they receive is representative sentences from the language generated by the target grammar. However, lacking much of the detail, at the time there was virtually no way to make this theory fit with observations about what children actually did. The LAD was some sort of ‘black box’ that if one fed linguistic data into it, out popped a hypothesised grammar, but just what went on inside the box was little understood. Thus the theoretical approach to the study of language acquisition and the experimental approach, which investigated children during the process of acquisition seemed miles apart with little chance of meeting up. 3 Chomskyan Inspired Theories of Acquisition This is not to say that there were no attempts during this period to try to account for child language acquisition patterns using the kind of linguistics that Chomsky introduced. In 1963 Martin Braine proposed to account for the early two word stage in terms of a simplified phrase structure grammar, which he called a Pivot Grammar. The idea is that children operate with a simplified set of categories, split into two: pivots and open categories and sentences are constructed from these by combining them following a simple phrase structure grammar: 2 Language Acquisition – Theories of Language Acquisition (2) S→OP S→PO S→OO So, for example, if the child had categorised the word see as a pivot and the words daddy and baby as open categories, the following sentences would be possible: (3) a b c daddy see see baby daddy baby The idea was that from this simple grammar the child was able to work up to a more complicated one in which there were more categories and more complex rules, including transformations. This idea however, although initially popular, suffered a number of problems. First it is not clear how entertaining a grammar which is clearly of a different nature to adult grammars is supposed to help the child to eventually acquire an adult system. One would have thought that if human language is something which comes from having a human mind, that children’s grammars should be of the same nature as adult grammars and that switching radically from something which is nothing like an adult grammar would hinder rather than help the process. Moreover, it was also pointed out that even at this stage, the similarities between child and adult language are greater than one would expect if children’s grammars were so radically different. For example, the word orders that children use on the whole tend to be alike to the adult language. This is obviously difficult to account for it children and adults make use of very different grammatical systems. Indeed, the evidence, such as it is, seems to indicate that even at this early stage, children operate with similar categories to adults, at least in terms of nouns, verbs and adjectives. As we know, the functional categories seem to come ‘on line’ along with the syntax spurt at about 2 and a half years. This is again something that the adoption of a pivot grammar would fail to account for: why would there be a slow development of grammar from the two word stage until about the age of 2 and a half and then a rapid expansion of grammar after this, coinciding with the development of functional categories, if children start with a pivot grammar and then abandon it (suddenly) in favour of something far more complicated? 4 The Effect of Constraints on Language Acquisition Theory As generative theory underwent development during the 1970s, moving from construction specific rules, to a constrained system using more general principle, then, for the first time, some notion of Universal Grammar became a tenable consideration. If rules are not directed at specific constructions in specific languages, then it can be proposed that the same rules are applicable to more languages. For example, many languages seem to have a wh-movement process, which moves interrogative elements to the front of the clause, though there are some differences as to what moves and where. A viable theory of Universal Grammar would of course make an innatist theory of language acquisition more specific. It could be claimed that children are born with the principles of Universal Grammar as part of their innate language faculty and it is this that aids them in their acquisition process. For one thing, an innate Universal Grammar imposes restrictions on 3 Mark Newson what the child can hypothesise about the language they are attempting to learn. This in itself would greatly help in the learning process as searching a restricted space of possible solutions for the right one is clearly an easier task than searching an unrestricted space. Universal Grammar defines what is a possible human grammar and therefore determines what is not possible and not to be hypothesised by the learner. This also answers the learning problem of Gold’s work in formal learnability theory: Gold showed that context free and context sensitive languages are unlearnable from positive data only (which seems to be what is available to children) given fairly generous assumptions about the learning situation and the conditions placed on the process. But the problem can be solved if human languages are not equated with the set of context sensitive or free languages, but rather constitutes a more limited set. Obviously, this is potentially what Universal Grammar does. It remains to be seen whether the set of languages defined by Universal Grammar are learnable in Gold’s model, but clearly that is a difficult question to ask until we know more about what Universal Grammar is. In a real sense, the notion of Universal Grammar also fleshes out what was vaguely reported as the LAD. The general learning situation assuming an innate Universal Grammar looks as follows: (4) data → Universal Grammar → particular grammar The linguistic data provide the child with evidence about which of the options made available by Universal Grammar are made use of in the target language, and so the child is able to home in on the correct grammar. Although the notion of Universal Grammar would be a step in the right direction for a viable innatist theory of language acquisition, it still remains to be shown how it could work. Obviously, Universal Grammar can only be seen as the basis of all human languages, not what generates human language as otherwise there would only be one language and this would not have to undergo any learning process at all. The fact that there is more than one possible human language and that children do undergo some period of language learning demonstrates that Universal Grammar must allow a certain degree of variation and that this is what is the cause of the learning process. We will discuss how this is done in the next section. 5 Principles and Parameters Theory By the time of the 1980s, grammatical theory had reached a stage at which grammatical rules were as generalised as possible: the X-bar principles of phrase structure and the movement rule Move could hardly be any more general. Such is the nature of such general rules that we can take them to be a part of all languages: all languages have phrases which have heads and these heads select complements, etc. in accordance with X-bar theory; all languages show some evidence of things moving from one place to another. Chomsky (1981) argued that these ‘rules’ are so general and therefore different to the kind of grammatical rules previously utilised in syntactic theories, that they should not be considered rules at all. Instead, he proposed that we term them ‘principles’. Principles are then what Universal Grammar is constructed from. However, principles cannot account for language variation. It may be true that all languages make use of the notions ‘head’ and ‘complement’, but languages differ in terms of how these elements are related to each other syntactically. For example, in English heads always 4 Language Acquisition – Theories of Language Acquisition precede their complements, unless the complement is moved. This is true no matter what the head. So, nouns, verbs, adjectives and adpositions all have following complements (which is why adpositions are called prepositions in English): (5) a b c d student [of linguistics] write [a letter] fond [of chocolate] under [the bridge] In a language like Japanese for example, the head always follows its complement (Japanese has post positions): (6) a [gengogakuno] gakusei linguistics(of) student [tegami o] kaku letter –acc write [hashi] shita bridge under b c Note that both English and Japanese are similar in some respects as they have phrases headed by nouns verbs and prepositions (and adjectives, I just couldn’t find one for Japanese), only the order differs: (7) NP NP N' N' N PP PP student of linguistics N gengogakuno gakusei linguistics(of) student Both of these structures conform to the same basic rules: (8) X' → X YP or X' → YP X Thus we might claim that while the X-bar principles are universal, languages differ in how these principles are realised and in particular in whether the head precedes or follows its complement. Thus we might suppose a general X-bar rule which makes no reference to order, saying that an X' contains the head and its complement, and then have a variant rules which says that either heads come first or last: (9) X' → X, YP a) head is first b) head is last The choice given in this rule is known as a Parameter: a variable part of a principle which may be set to one of a number of possible values. It is the existence of parameters, then, that give rise to language variation. The theory that follows from these assumptions is that Universal Grammar consists of a set of invariable principles which may come with a number of parameters. Each parameter has two 5 Mark Newson or more possible values that it can be set to. Universal Grammar, then, is similar to any possible human grammar, without its parameters set. Any specific language is the result of setting the parameters in a particular way. Thus we have the following model: (10) Universal Grammar + parameter settings = a specific language It also follows that it is the parameter settings that require learning. In learning English, the child does not have to discover that phrases have heads and complements, as this is true for all languages and is a principle of Universal Grammar and therefore given innately, but they do have to find out whether English is a head initial language or a head final one. Thus they must learn how to set the ‘head parameter’. Presumably this is not particularly difficult: all it requires is hearing one instance of a head initial phrase, such as see the ball, and the parameter can be set. Recall, this is the kind of thing that children show mastery of from a very early age. 6 Problems for Parameter Setting One fairly obvious problem with the parameter setting theory of language acquisition is that it appears to make the problem of language acquisition so easily solved that it is hard to see why it takes children as long as five years to complete. If it is just a matter of hearing one relevant piece of data for each parameter to be set, then surely language acquisition should be almost spontaneous! Of course, on top of parameter setting, children have to learn lexical facts and this, to a large extent, must be rote learning as the lexicon is entirely unpredictable information. But still, the evidence is that it is not just words that take time to learn, but syntax also develops. Recall however, that there are two spurts in the acquisition process, one where vocabulary increases and basic word combinations start to take place and the second where functional categories are learned and more complex syntactic processes start to appear. It has been suggested that these spurts indicate that language acquisition is to some extent biologically triggered, similar to the way teeth develop or the body undergoing development at puberty. Clearly these bodily changes are biologically determined – set to go off at some predestined time. The idea is that the development of language may also be subject to these kinds of maturational time lags and that the onset of certain linguistic notions is biologically determined rather than subject to a gradual learning process. If this is so, it would account for the sudden spurts that we see in child linguistic behaviour and it would further account for why parameter setting is generally spread out rather than being spontaneous. What is needed is some detail about exactly what matures and so what is available (and unavailable) to the child at any particular moment in the acquisition process. It seems clear that what develops during the vocabulary spurt is some of the basic concepts which allow combinations of words, particularly the kind of semantic relationships for forming basic propositions. For example the idea of predicate and argument seems to be missing at the one word stage, but is present once two or more words start to be combined. The thematic words which take part in these combinations are also what are evident at this stage and it is verbs, nouns and adjectives which predominate. During the syntax spurt it is the functional categories which seem to mature. Current syntactic theory holds that it is the functional words which play a central role in the more complex aspects of syntax and so it is not surprising that these syntactic processes are absent before functional words are present and that they should rapidly develop after the onset of these elements. 6 Language Acquisition – Theories of Language Acquisition A more worrying criticism of parameter setting is that it virtually reduces an otherwise highly explanatory theory of language to mere description. This argument is based on the question of what counts as a parameter. Obviously as parameters are the mechanisms for language variation, it is parameters which determine the possible range of linguistic variation. But in principle anything may be parameterised and any parameter can have any conceivable value. The head parameter we saw above is a simple case as there are only two possible ways to order the head and the complement and both of these are realised in languages. But if there is no limit on what we can consider to be parameterised, we are free to assume that differences between any two languages are to be captured by a specific parameter setting. The absurd limit to this would be for all languages to be the result of unique parameter settings which are not apparent in any other language. Thus there would be a +Spanish parameter setting and a +Swahili setting, etc. This would be perfectly consistent with the notion of Universal Grammar under the view of principles and parameters theory, but it would render the whole theory without explanation. The response to this problem has tended to build into the notion of Universal Grammar some restrictive theory of parameters, though it has to be said that nothing has been particularly persuasive. For example, one of the earliest ideas about parameters is that given that they were embedded in a theory in which linguistic complexity arises from the complex interaction of simple and general grammatical modules, that parameters, though simple in themselves could affect grammars in extensive and yet subtle ways by changing the conditions in which the modules interact. In effect then, a small change in a parameter setting could be enough to have wide and fairly drastic effects on resulting language. This would account for why languages can seem to be so different from each other and yet be related to the same Universal Grammar. Note that this would also aid the acquisition process too as it means that the amount of data that can be used to trigger a parameter setting is much wider. Probably the most well known of this kind of parameter was the pro-drop parameter, which, amongst other things, determines whether a language can have an empty pronoun subject of a finite clause or not. English is a non-pro-drop language as its finite clause subjects have to be overt: (11) a b he sleeps * sleeps Hungarian is a pro-drop language as it can have a covert subject in a similar case: (12) a b ő alszik alszik Thus, there are two settings for this parameter: pro-drop and non-pro-drop. It was in fact more technical than this, resting on a certain property of the tense and agreement inflection of the language, but we need not go into these details. However, it was also claimed that the prodrop parameter was responsible for other phenomena too (again, the technicalities will be avoided, but it should be noted that the facts did follow from the same properties of the inflection, and wasn’t just a stipulated association as might seem from the present presentation). For example, the presence of pleonastic (meaningless) subjects in a language correlates with the language lacking null subjects in finite clauses: 7 Mark Newson (13) a b it seems that John is ill sembra che Gianni sia ammalato seems that John is ill In English the it subject is necessary for a grammatical sentence, but in Italian, a pro-drop language, there is no such element. Another distinction between pro-drop and non-pro-drop languages is the ability to invert the subject with the VP. This is possible in Italian, for instance, but not in English: (14) a b ha telefonato Gianni * has phoned John Finally, certain long distance movements are possible in pro-drop languages, seemingly violating certain Island conditions, which are not possible in non-pro-drop languages: (15) a b che credi che verrà * who do you believe that will come Thus, if we set the pro-drop parameter one way, we get a language which can drop pronominal subjects, which doesn’t have pleonastic subjects, which can invert subjects with VPs and which can move wh-elements over long distances. If we set the pro-drop parameter the other way, we get a language which has overt subject of finite clauses, which has pleonastic subjects, which cannot invert subjects and VPs and which cannot move whelements over long distances. Note that the last fact is quite complex and the data is not likely to be the sort of thing that children will be exposed to. But all they need is to know whether the language has null subjects or not, and that will tell them whether wh-elements can move long distances or not and they will not have to hear sentences such as in (15) to know this. For, the important point is that this idea may serve to limit the kind of thing that we can propose as a possible parameter. If all parameters are like the pro-drop parameter, affecting a wide number of linguistic phenomena, then we are not entitled to come up with a parameter to account for a single difference between two languages. Unfortunately, this programme did not really succeed in that the pro-drop parameter, although a spectacular example of what parameters could do, seemed to be fairly unique in this way. Most parameters that were proposed were like the head parameter, which just deals with the order of heads and complements and plays no role in other linguistic phenomena. Moreover, as further languages were investigated, even the pro-drop parameter was eroded as it seems that there are pro-drop languages which do have expletive subjects, which cannot invert subjects and VPs and there are non-pro-drop languages which can move wh-elements over long distances. Thus, the only thing the pro-drop parameter really determines is whether the language allows null subjects or not. Hence the parameter is only associated with one observable linguistic property. A more successful restriction follows work by Borer (1984), which showed that many linguistic differences between languages can be put down to properties of their functional categories. Just like the difference between pro-drop and non-pro-drop languages seems to be correlated with how rich the inflections of the language are (pro-drop languages have rich inflectional systems and non-pro-drop languages have poor inflectional systems: compare 8 Language Acquisition – Theories of Language Acquisition English and Hungarian in this respect). Borer demonstrated that other differences between languages could be put down to properties of other functional elements and hence if parameters are what deal with language variation, it seems that parameters are limited to properties of functional categories such as inflections, determiners and complementisers. From this perspective, apart from superficial differences, all languages are the same with respect to their argument-predicate structures: the equivalent verb to smile in all languages will take just one argument, whereas the equivalent to give will take three. The Functional Parameterisation Hypothesis works well for many linguistic differences, but it is difficult to see how differences such as the head parameter can be reduced to the properties of functional elements as it obviously affects the order of non-functional elements such as nouns and verbs. Therefore even if some parameters are limited to the properties of functional elements, it seems that we also need other parameters which are not and hence this is not a fully restrictive theory. 7 A brief word about acquisition theories from other grammatical perspectives In Chomsky’s latest thinking about language, the Minimalist Programme, linguistic differences have been reduced to whether elements move overtly or not and thus parameterisation is restricted to this distinction alone. It has to be said however, that the application of this theory is not as wide as the theories of the 1980s (e.g. Government and Binding theory) and so it is not at all clear whether this assumption can be made compatible with all observable linguistic differences between languages. Optimality Theory, on the other hand, has come up with an alternative to Parameter setting as a theory of linguistic variation and acquisition. In OT, constraints conflict with each other so that they require opposite things of a grammatical structure. The conflict is settled by ranking the constraints so that in cases of conflict the highest ranked one will be conformed to and the lower ranked one violated. The point is, then, that it is the ranking of the constraints that determine what is grammatical in a language and therefore if the ranking differs, different things will be grammatical. Ranking therefore accounts for linguistic variation. It follows that it is constraint ranking that must be learned by a child acquiring the system: the constraints themselves can be assumed given by Universal Grammar. Formally this is a very different kind of acquisition process to Parameter Setting and it can be investigated in different ways. There are interesting results in this area, but it would take us too far from our current position to be able to go into any details. 8 Conclusion It is very difficult not to believe in an innate ability in children to learn language. Chomsky has argued forcefully that this innate ability must be specific to language and not a kind of general ability to learn well (how could infants learn whether or not long distance whmovement is possible in their language when the data needed to figure this out from is far more complicated than could be reasonably be expected to be available to a child). However is was only once we had any reasonable idea of what Universal Grammar was that a realistic innatist theory could be presented. While this is still far from perfect, and obviously the theory of Universal Grammar and the dependent theory of language acquisition changes as linguists views on language develop, the notion that came about in the 1980s was enough for the theory to make predictions about what actually goes on in the learning procedure and as such, for the first time, there was real contact between theoretical linguists and child language acquisition specialists. The parameter setting theory spurred a great many investigations into 9 Mark Newson details about how children learned specific linguistic phenomena and in turn this research informed linguistic theory about what was a viable theory and what was not. Although of late, with the Minimalist Programme retreating into more theoretical questions, the contact between linguists and acquisitionists has not been quite so productive, principles and parameters theory has shown what is possible when linguistic theory is able to develop in this direction. References Bloomfield, Leonard 1933 Language, Rinehart and Winston, New York. Borer, Hagit 1984 Parametric Syntax, Foris, Dordrecht. Braine, Martin D. S. 1963, 'The Ontogeny of English Phrase Structure: the First Phase', Language 39, 1-13. Chomsky, Noam 1957 Syntactic Structures, Mouton, the Hague. Chomsky, Noam 1959 ‘Review of B.F. Skinner’s Verbal Behaviour’, Language, 35, 26-58. Chomsky, Noam 1981 Lectures on Government and Binding, Foris, Dordrecht, Holland. Gold, E. M. 1967 ‘Language identification in the limit’ in Information and Control, 10, 447– 474. Rizzi, Luigi 1982 Issues in Italian Syntax, Foris, Dordrecht, Holland. Skinner, B. F. 1957 Verbal Behavior Appleton Century Crofts, New York. 10