VII

advertisement

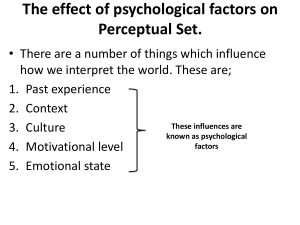

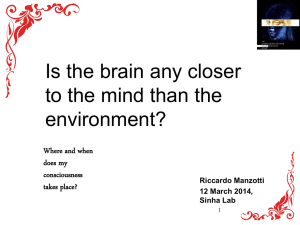

The Two- Concept versus the Interdependence Approach to Perception I. The Two-Concept Claim According to David Chalmers the ‘hard problem’ of consciousness is due to the fact we have two independent concepts of mind. The first is the phenomenal concept of mind. This is the concept of mind as conscious experience, and of a mental state as a consciously experienced state. This is the most perplexing aspect of mind. The second is the psychological concept of mind. This is the concept of mind as the causal or explanatory basis of behaviour. ...There should be no question of competition between the two notions of mind. Neither of them is the correct analysis. They cover different phenomena, both of which are quite real.1 While there are technical complications in, and competing accounts of, the way in which we should make sense of the location in the natural world of the psychological mind, we have a general sense of how to go about this, mainly by appeal to functional characterizations of aspects of the mind conceives of under the psychological concept. But there is serious bafflement about the very idea of the phenomenally conceived of mind being part of the natural world, precisely because of the independence of these concepts. There is a conceptual gap between them of a kind that means we can’t help ourselves to the functional characterizations we use in spelling out the functional concepts in order to make sense of the location of the aspects of mind thought under the phenomenal concept. This independence of the two concepts shows up, says Chalmers, in our specific everyday mental concepts "A specific mental concept can usually be analyzed as a phenomenal concept, a psychological concept, or as a combination of the two." Pain 1 The Conscious Mind: In Search of a Fundamental Theory (1996), p.x is given as an example of a concept, which "in its central sense" is phenomenal. The concepts of memory and learning, on the other hand, "might best be taken as psychological concepts". As a prime example of mental terms that "lead a double life" Chalmers cites perception.. It can be taken wholly psychologically, denoting the process whereby cognitive systems are sensitive to the environmental stimuli in such a way that the resulting states play a certain role in directing cognitive processes. But it can also be taken phenomenally, involving the conscious experience of what is perceived.2 Everyone would agree that when we use our everyday concepts of perception, e.g. that of vision ,we think of vision both as something that delivers a distinctive phenomenology and as a way of picking up information from the environment. What the two-concept claim says is that these aspects fall under two mutually independent concepts. As I will be reading the claim it says the following We can give an exhaustive account of the nature of our everyday perceptual concepts by separating out the phenomenological and psychological ingredients in such a way that (a) We get the extension of the phenomenological ingredient right without any essential appeal to ingredients we use to determine the extension of the psychological ingredient (call this the Phenomenal Independence clause) (b) We get right the extension of the psychological component right without any essential appeal to the materials we use to determine the extension of the phenomenological component. (Call this the Psychological Independence clause). (c) In getting right the extension of each component we are deploying a distinctive concept, a psychological one for the psychological ingredient, and phenomenal once for the phenomenal ingredient. Applying the two-concept approach, thus formulated, to the concept of vision, say, the claim would be as follows. When, on the basis of introspection, one judges that 2 Ibid. p. one is seeing a white rabbit, say, one is actually making two claims. One is about the instantiation of properties identified by the use of a purely phenomenal concept of vision; the second is a claim about the instantiation of a properties identified by a purely psychological concept of vision. Each of these can be got without any reference to the materials used, essentially, in getting right the other. Chalmers’ two-concepts claims are rooted in the debate I sketched in the first chapter. To say we have two concepts here is to give an account of conceptual independence to be cashed by appeal to the absence of a priori entailments from, for example, truths about the instantiation of the psychological visual properties to truths about the instantiation of phenomenal visual properties. A central tenet of Chalmers' general approach to the problem of consciousness, a tenet argued for extensively, is that where there are no a priori entailments there are no reductions. If this is true, in turn, then on the face of it, truths about the instantiation of psychological visual properties do not entail, simplicter, truths about the instantiation of phenomenal visual properties. This, in very crude form, is his challenge to materialists. More specifically, his claims here are directed at against two positions we referred in the first chapter. The first, the ‘Type A’ Materialist, will, in effect, deny the first, Phenomenal Independence Clause, and uphold the second, Psychological Independence clause. Such a theorist will say that the phenomenal aspects of our concept of vision, say, can be exhaustively accounted for by appeals to the materials we use in giving an account of the psychological components of our concepts of vision. (If this is true, the a priori reduction goes through). The second position, that of the Type B Materialist, will say that, contra the Type A Materialist, there is a sense in which both clauses are true, so that there are indeed no a priori entailments, but this does block reductions. The sense in which the Phenomenal Independence clause is true requires distinguishing between two ways a concept might relate to essential features of the property referred to. On one, the concept makes explicit those essential (‘metaphysically necessary) features, on the other it doesn’t. Thus it might be claimed, the concept of ‘H2O’ is an instance of the first, and the concept of ‘water’ is an instance of the second. The claim might now be that the sense in which both clauses of the conceptual independence claim are true is that they should be interpreted in these terms. The psychological concepts make explicit the essential properties of a visual state and the phenomenal properties do not. But that is still consistent with a posteriori reductive identity claims being true about the properties singled out by each concept, and that is enough to deliver materialism. Now, the debate here is a version of a debate about the answers we should give to what I labeled the Metaphysical Implications Question in Chapter 1: are a priori entailments from the physical to the phenomenal possible? And, do intelligible reductions depend on such entailments? Here, as in the previous chapter, I am going to step back from such questions and look at the two-concept claim in its own right, considered as a claim about our ordinary concept of perception. One question is: how does one go about establishing such a claim? A second question is: what kinds of opposition does it face? II. Zombies It has to be said that on the face of it we do not normally think of statements to the effect that one sees such and such as consisting in two distinct, mutually independent statements, each exploiting a different concept of seeing. But, the claim might be, that is because we don’t normally think about our concepts at all. Furthermore, there is an immediate test in which anyone can engage which shows that in fact this is the correct account of our concepts as we use them. The test is the claim that zombies are conceivable. To tailor it to our case, the claim will be that anyone will find the claim that a perceptual duplicate is conceivable, an entity who perceives as we do, when this is functionally defined, but has no phenomenal consciousness. The mere conceivability of such a scenario establishes the truth of the Psychological Independence Claim, it might be said. It establishes, that is, that we can get right the extension of the psychological ingredient in our everyday concept of vision without appeal to phenomenal ingredients. To get the second, Phenomenal Independence Claim one might adopt a similar strategy and say that we can easily conceive of creatures with experiences just like our visual ones, say, but who fail to instantiate any of the psychological/visual properties we do. An extreme case would be brains in a vat, who, it might be claimed, we can easily conceive of as having exactly the same visual experiences as we have, but no perceptual mechanisms at all. And this shows, it might be claimed, that we can get the phenomenal components in our everyday concept of vision right with appeal to the psychological ones. Now, as we have seen, there are debates about the nature of the determinants of phenomenal character, which would have a direct impact on the truth of the Phenomenal Independence Claim. In particular, if you hold either an externalist representational theory, or a relational theory you will deny that the brain-in-a-vat thought experiments establish the truth of the Phenomenal Independence Claim. So you will need to take a stand on the substantive debate about the nature of phenomenal character if you appeal to such thought experiments, and adopt either an internalist represent representational account or a sensational account. Although Chalmers himself does not discuss this at length, his reference to visual sensations in describing the phenomenal character of visual experiences suggests he would adopt a sensational line. These debates about phenomenal character also affect how you will react to the zombie thought experiment For example, if you adopt an externalist representational account of the determinants of phenomenal character then you will deny that zombies are conceivable. What this brings out is a familiar point often made, that such thought-experiments cannot be treated as a wholly conclusive datum, when weighed up against independently motivated accounts of the nature of our concepts. The question this raises is: what, if anything counts as a sufficiently independently motivated account of our concepts, one that could withstand the prima facie compellingness of the claim that zombies just are conceivable given that we seem to have no difficulty in understanding zombie stories. Rather than tackle this head-on, let me put on the table a different account of the relation between the phenomenal and psychological components in our everyday concept of vision, and use this to generate a different interpretation of the way we understand the zombie stories, one which does not directly exploit any particular account of the determinants of phenomenal character. III. The ‘interdependence' response to zombie stories. Something I will call the 'interdependence approach’ to our concept of perception makes the following two claims. First, we cannot get right the extension of the psychological component in perceptual concepts such as ‘vision’ without essential appeal to the phenomenal ingredient. The Psychological Independence Claim is false. Second, we cannot get right the extension of the phenomenal ingredient m such without essential appeal to the causal explanatory ingredient. The Phenomenal Independence Claim is false. In subsequent sections I will turn to the substantive issues at stake here, and to head-on debates between this approach and the two-concept approach, but to give something of its flavour let me first lay out how it would deal with the zombie thought experiments. There is no doubt, the claim will be, that we (adults and children) have no difficulty in understanding stories about zombies. We also have no difficulty in understanding stories about men who morph overnight into giant beetles, invisible people, trains who think they are late, or lions who fly through the sky. And one possibility, indeed, is that in doing so we exploit a distinct concept of ‘man’, say, which unlike our usual concept, is such that being a man doesn’t rule out being a beetle; or a distinct concept of ‘train’, which unlike our usual concept, is such that one can be both a train and a thinker; and so forth. This is the literal,‘two-concept’ solution. Another possibility, however, is that in understanding these stories we employ a ‘metaphorical’ strategy of understanding. On one compelling, and particularly pertinent account, this consists in bracketing off or ignoring those aspects of our concepts that refer to features we think of as essential to the property our concepts refer to, while hanging onto surfaces features only, the looks of a beetle say, or the colour of roses when we talk of someone’s cheeks being roses. 3 If this is what is happening here, there is only one concept in play, metaphorically deployed. We are subtracting consciousness from our concept of perception when we go along with the story, in the same way one subtracts reference to plants when one understands the claim: ‘her cheeks are roses’. The point is that what we say about the concepts in play in any particular case of understanding a story 3 See Avishai Margalit’s ‘Open Texture’ in Meaning and Use cannot be settled by the simple fact that we can understand the story. Just to drive this home, consider the following story,, derived from the scenario described in Jackson’s ‘knowledge argument’. Suppose Mary is a blind neuroscientist who acquires all the knowledge there is about the information processing mechanisms involved in vision. Suppose suddenly she regains her sight. She will say: "Oh, this is what it is like to see!” On the two-concept approach she will now be employing a new concept of perception; on the interdependence approach she will only now be acquiring full understanding of what her earlier concept meant. Our understanding of the story on its own does not determine which is the correct account here. More generally, we can certainly stipulate that whatever is left over from our concept of lion, say, once we have subtracted everything that is inconsistent with lions flying, constitutes a separate concept, and that is the concept we deploy when we understand the story. Similarly, we can stipulate that when we understand a story about a perceiving zombie, the concept of perception we deploy is a concept from which everything that is inconsistent with absence of consciousness has been subtracted. And once such stipulations are made, many interesting questions arise about the relations between these various ingredients, and how and whether they relate to logical and metaphysical possibility. But, on the face of it, such stipulations tell us nothing about our everyday concepts and their referents unless they are backed by independent reasons for thinking that these stipulations merely formalize something implicit in our everyday concepts. Of course, defence of the appeal to zombies might go through a claim to the effect that our ordinary concept is incoherent or confused, and needs cleaning up along two-concept lines. That is a possible claim, but not one yet made, and not, I think, the line Chalmers himself would want to take. I come back to such possibilities in the next section when we consider further arguments for the twoconcept claim, ones that do not relay on appeals to counterfactual stories. For now I will take it that the understandability of zombie stories, on its own, does not tell in favour of either the two-concept or the interdependence claims. IV. Cognitive psychology and our concept of perception Suppose you concede that the understandability of zombie stories does not serve as conclusive evidence against an interdependence account. You might then say that we in fact have strong independent reasons for adopting the two-concept account, and that they are what our understanding of the zombie story is in fact tapping into. Perhaps the most obvious move to make here will be to point to the huge advances that have been made in information processing theories of perception, accounts that are progressively being supplemented by the findings of brain imaging techniques, and chemical and neurophysiological investigations of the working of the brain. The claim will be that, say in the case of vision, scientists are working with a concept of vision the extension of which is determined wholly independently of any appeal to phenomenology, which shows, at least, that the Psychological Independence Claim is true. Well, whether or not vision scientists are working with a phenomenologyindependent concept of vision is a delicate matter to which I return. But to the extent that it is true, I am not sure this is something the advocate of the two-concept approach should appeal to. Just to give two examples: in the case of vision it is increasingly being argued that, from a scientific point of view, there is no one kind of input-output function that should count a visual. For example there is a growing consensus that the visual system delivers distinct types of output to the action and recognition systems. From a scientific point of view this does not matter, we can label one the 'pragmatic' system and one 'semantic' system. 4Or consider the case of attention. What is attention? William James famously responded to this question saying that everyone knows what it is; it is the active selective bringing to the mind of some objects in the scene while discarding others. A leading authority on information processing accounts of attention Harold Pashler has claimed that contra James, the answer is: there just is no such thing as attention. What he means is that as soon as we begin delving into the complex information processing tasks that our perceptual systems need to perform, which we informally describe as attentional tasks, we see that there is nothing functional that holds them together5. None of this matters when we are concerned with the scientific enterprise of examining how we process information from the environment and respond to it. But it matters when we ask which if any of these many functions is supposed to be identical to an independently identified, ‘folk psychological’ functionally defined purely psychological notion of vision or attention. On the face of it, at least, any answer we give here has an arbitrary, stipulative feel. The right response, surely, is eliminativist. Our folk psychological functionally-defined concepts are good starting points, to be discarded as science progresses. Now this is, of course, a line the two-concept theorist might want to take, but it is not, as I have understood it, what the advocate of the two-concept approach has in mind, at least intially In particular, it would yield a quite different claim from the one we are considering. What it would yield is that the claim that on inspection our ordinary concept of vision breaks down into one phenomenal concept plus a multitude 4 5 See e.g. Milner and Goodale, The Visual Brain in Action. pp See introduction to Harold Pashler Attention, 1998. pp of scientifically defined concepts, which is far more revisionary than the original twoconcept claim. An advocate of the two-concept approach might concede this but then say that this modification of the original claim is one we should endorse, given the intolerable consequence of endorsing the alternative we are considering, namely the interdependence approach. As I have introduced it, to adopt such an approach is to say that the extension of the psychological component in our everyday concept of vision, without appeal to the materials we use to get right the phenomenal component. To see what the objector has in mind, let me now be more specific about what exactly this means. So far, phenomenal concepts in general have been defined as the concepts we use when we introspect to describe what our experiences are like. Let us now extend this to our concepts of perception, sticking to the example of vision, and say that grasp of the phenomenal component in our concept of vision requires the capacity to reports on how things look to one based on introspection of visual experiences. Getting right how things look to one, in turn, requires sensitivity to the actual character of the experience, where such sensitivity is constitutive of grasping that aspect of our visual concept. To say that we cannot get right the psychological component in our ordinary concept without appeal to the phenomenal component, commits one, as I will be understanding it, to saying that the extension of the psychological ingredient is constrained by the deliverances of phenomenology, those we are sensitive to when using ‘look’ and it cognates in reporting on visual experience. The claim we are considering will say that the arguments deployed above against the two-concept appeal to vision science show why this aspect of the interdependence claim is simply false. What we have seen is that vision science, for example, has it own allegiances and progresses unimpeded by anything phenomenology delivers. Now, there is something obviously right here, which an advocate of the interdependence claim should straightforwardly endorse. Much work on attention and vision is controlled, as I said above, by its own allegiances, and this is something an advocate of the interdependence claim can and should acknowledge. What is being denied by an advocate of the interdependence is that such work determines the extension of the psychological component in our everyday concept of perception. What is being asserted is that to the extent that work in vision science is relevant to determining the extension of our everyday concept (I return to discussion of this issue in the last section) it is essentially controlled by the deliverances of introspection (as in fact much vision science is). That means that phenomenology controls what, if anything, counts on any occasion as a scientific investigation of the process underpinning vision, on our common sense understanding of the concept. And there is nothing in the actual practice of vision science that tells against this conditional claim. I suspect that the main resistance to the very idea that phenomenology could have any constraining input into what science tells use about perception stems from adherence to the Phenomenal Independence Claim. Suppose you hold that getting phenomenology right is a matter of, for example, getting right the character of sensations we are presented with this. Then you will say that this cannot serve to constrain a correct account of the extension of the psychological component, on pain of going over to some form of idealism about the latter. That is right, but it brings us to the question of how we should understand the denial of the Phenomenal Independence Claim, and the general question of what in fact determines phenomenology. We also need to address the question of how, in fact, we should conceive of the psychological component of our everyday concept. The assumption implicit in the discussion in this section is that its extension will be determined by the deliverances of perception-science, but what we have said about the breakdown of functions under scientific investigation gives us good grounds for denying this assumption. This is the issue to which we now turn. More specifically, the issue I now want to consider is what the interdependence approach, as I will be interpreting it, actually says about both the phenomenal and the psychological components in our everyday concept. As to the discussion in this section of the relation between science and phenomenology, the central point to take away from it is that appeal to work done on the information processing underpinning perception in the various modalities does not of itself lend any support to the claim that we have an independent psychological concept of perception, as the two-concept theorist conceives of such independence. In particular, we cannot appeal to such work to supplement appeal to the zombie stories to make good the Psychological Independence Claim. V. The interdependence account of our concept of perception When developmental psychologists investigate children’s acquisition of our concepts of perception in the various sensory modalities, what they are looking for is the progressive grasp children display of the enabling conditions associated with each modality, what counts as a barrier, how you need to be located relative to an object in order to perceive it in that modality, and so forth. What the developmentalists are working with is what on many accounts constitutes our understanding of what it is to see, hear, feel etc, On such accounts, grasping our general concept of perception is a matter of understanding what in general is required for perceiving an object, namely, that one be in the right place and the right time, there be nothing in the way and so forth.. Grasping particular modality concepts, say vision, on this approach, is a matter of grasping a specification of such enabling conditions. This is often called the ‘primitive theory’ approach to our ordinary concept of perception. Grasping the concept is matter of grasping such a primitive theory of the enabling conditions of perception. The first claim of the interdependence approach, as I will be understanding it, is that the primitive theory account captures, in rough terms, the basic psychological component in our everyday concept of perception, where that is understood, broadly as the ingredient in our concept that refers to perception being a way of picking up information about the environment. In this sense, Chalmers’ characterization of this component in our everyday concept as ‘denoting the process whereby cognitive systems are sensitive to the environmental stimuli in such a way that the resulting states play a certain role in directing cognitive processes’ is a bit too fancy, but, for the moment, nothing much hangs on that if its taken merely as an abstraction from, or addition to, what the primitive theory says. How does the ‘primitive theory’ component of our concept of perception relate to phenomenology? When we think of children acquiring the concept, no one would deny that the distinctive phenomenology of our experiences in each modality is an aid to acquiring the concept. But the interdependence approach makes a stronger claim. It denies that such experiences merely fix the reference of our concept of perception. It says that getting right the extension for each modality of the psychological component is impossible without the use of the phenomenal component in the concept, the ingredient that is exploited in reports on how things look, feel, sound and so forth. This is how we should, initially, understand the claim that the Psychological independence Claim is false As to the Phenomenal Independence Claim: If you hold either an externalist representational theory of the determinants of phenomenal character, or a relational theory, you will say that getting right what ‘looks’ 'feels' etc mean, when used in reports of experiences cannot be done independently of appealing, essentially, to the psychological component in our everyday concepts, without appealing to the idea that perception is a way of picking up information from the world, as what this information is goes into determining the character of the experience. You will hold, that is, that the Phenomenal Independence claim is false, for that reason. But here we come to the distinctive feature of the interdependence approach. Most externalist representational accounts adopt a version of the Psychological Independence Claim. They will say that we can give an analysis of the phenomenal component in our everyday concept by appeal only to the materials that go into spelling out what the psychological component consists in. Thinking of perception as a way of taking in information from the environment yields a notion of representation that we can then appeal to explain what it is to have a perceptual experience in a way that makes no essential use of the way we think of perceptual experiences on the basis of introspection. And this is what the interdependence approach denies. What does this denial amount to? We need a characterisation of what is required for getting the phenomenal component right, which the only the interdependence theory will hold is required for getting the psychological component right. More specifically: until now our only characterisation of phenomenal concepts has been that they are the concepts we use on the basis of introspection to describe what our experiences are like. We now need to introduce a more specific characterisation, one that would serve to to give substance to the interdependence approach. To this end, the interdependence approach, as I will be understanding it, makes the following two claims. (1) Phenomenal concepts are essentially perspectival. (2) We need to use such concepts to get right the extension of the psychological component of our concept of perception. To say that phenomenal concepts are essentially perspectival is to say, loosely at this stage, that getting right the extension of such concepts depends on having experiences with the phenomenal properties to which the concepts refer, and the capacity to use them on the basis of introspection What the interdependence approach says is that such concepts are essential not only for getting right the extension of the phenomenal component in concepts such as vision, but also for getting the extension of the psychological component . Our earlier Mary, on this view, could not get right the extension of concepts such as vision because,, lacking visual experiences she was not in a position to grasp the perspectival ingredient in our everyday concept. VI. Back to the Conceptual Question So there we have it: a statement of the interdependence claim, a statement of the twoconcept claim, and a suggestion to the effect that arguments so far considered in favour of the latter over the former are not convincing as they stand. To get further we need to see, first, what the point of the interdependence claim is relative to issues we have so far considered under the conceptual question heading. This, in turn, will lead us to major challenge it faces, a challenge that can be formulated into an argument in favour of the two-concept claim. If the two-concept claim is true, the relational theory is false, and we cannot appeal to it to show that we can make sense of the location of token experiences in the natural world. If the interdependence claim is true, the relational theory is still in the offing, as far as token experiences are concerned. So, that is one point, relative to issues discussed in the previous chapter, of pitting the two approaches against each other. But the introduction of the interdependence claim does more than that. McGinn’s complaint against externalist representational theories was that they leave out what he calls ‘the interiority of consciousness’, its ‘subjectivity’. They leave out what it is for an object to be ‘present to the subject’ (his italics). I suggest that a great deal, though not all, of what he was after on that score is captured, precisely, by the insistence that phenomenal concepts are essentially perspectival. This is one way of explaining what doing justice to the subjectivity of consciousness consists in (I say more about this in the next chapter).And it would certainly rule out many versions of a representational theory. For example, Michael Tye appeals to David Marr's theory of the stages in visual information processing to give a representational account of phenomenal character. He acknowledges that the way we in fact think of the character is via perspectival modes of presentation. But he denies these are essential for getting right their extension: their essence is delivered by Marr’s theory, a theory which at the same time does justice to our understanding of vision as a way of picking up information from the environment, does justice, that is, to the psychological component. Tye’s approach is one of many that, in effect, deny the Phenomenal Independence Claim but uphold the Psychological Independence Claim. On the interdependence approach, perspectival concepts are essential for getting right the essence of what it is like, the essence of phenomenal character. And this goes, as I noted, at least part of the way towards meeting McGinn’s concerns about representational theories. So, one thing the interdependence claim introduces into the scene, from the relationalist’s point of view, is a way of doing justice to the subjectivity of perceptual experience, thus, so far, cashed. But as I will be understanding it, it aims to do much more than that. The suggestion that if the relational theory is true it shows that we can make sense of the location of consciousness in the natural word was greeted, in the previous chapter, by the claim that making sense of the location of token experiences is not the same as showing that we understand of the location of consciousness itself in the natural world. Consider now the proposal that the interdependence account of our concept of perception shows that we do make sense of just that, in the case of perceptual consciousness. Getting right the extension of our concept of perception, the claim will be, both requires the use of essentially perspectival concepts, in a way that brings in consciousness, and, at the same time, requires the use of spatial and physical concepts in getting right the psychological component, cashed along primitive-theory lines. The essential use of the later shows that we can and do makes sense of the location of perceptual consciousness in the natural world; it is built into our very basic perceptual concepts. Here we come to the issue I flagged up towards the end of the previous chapter, under the heading of the Analysis Claim. This is the claim that showing that we can make sense of the idea that phenomenal properties are located in the natural world requires showing that we can give an analysis of our phenomenal concepts in physical terms. I suggested that Chalmers is, at least implicitly, committed to it. Such commitment is implicit, in particular, in the fact that the debate I sketched in the first chapter, in which his position is rooted, does not even consider the interdependence account. The latter, instead of providing an analysis, of one kind of concept in terms of the other, links phenomenal and spatial concepts in a relation of mutual interdependence in specifying the extension of our concept of perception. The claim that I now want to consider is that the interdependence account, precisely because of the absence of analysis is at best useless, as far as the Conceptual Question is concerned, and at worst incoherent. One major reason for adopting the Analysis Claim, and not even considering the interdependence approach, rests in the idea that the only answer to the Conceptual Question that would be metaphysically interesting is one that would show that we can make sense of consciousness in the natural world via an analysis of our phenomenal concepts in the objective terms used in microphysics. This is what would show that we can really make sense of the location of consciousness in the world as it is in itself. And the thought might be that precisely the perspectivalness of our phenomenal concepts is something we need to show can be dropped if we are to show that location of consciousness in the objectively conceived of natural world is intelligible. If the interdependence approach insists not only that phenomenal concepts are essentially perspectival, but also that they are essential for getting right the extension of our concept of perception, it is not even in the ballpark of delivering an interesting answer to the intelligible location question. More strongly, the claim a defender of the two-concept claim might make is that it is not even coherent.. Either we say the extension of our concept of perception is determined via the use of objective spatial and physical concepts; or we say it is determined by the use of essentially perspectival concepts. We can’t have both working in tandem. Given that we think that spatial and physical concepts are essential for getting right the psychological component of our concept of perception, if you also hold that perspectival concepts are essential for getting right the phenomenal component, the obvious move to make is to say we have two separate concepts, to adopt, that is, the two-concept approach. Actually, once the objectivity issue is highlighted, it appears that relational theory considered as an answer to the Perceptual Access Question, is also under the threat. Recall, the idea was that the relational account does justice to the claim that consciousness give us direct access to the world out there, the word as it is in itself. Suppose that we say that access to the word as is in itself is a matter of representing it objectively. If getting the phenomenal character of perceptual experiences requires the use of essentially perspectival concepts it seems that precisely for that reason, consciousness cannot reach all the way out to the world as it is itself. In brief, it appears that the interdependence account of our concept of perceptual, in virtue of attempting to do justice to the subjectivity of perceptual experience, rules itself out from giving an account both of what intelligible location of perceptual consciousness in the natural world amounts to, and of what it is for consciousness to provide us with access to the natural world. That is the challenge it must now meet, and the problem we turn to in the next chapter. To sum up where we have got to so far: I have been suggesting that neither appeal to our capacity to understand stories about zombies, not appeal to the practice of the perception-sciences provides independent grounds for preferring the twoconcept claim to the interdependence approach. I will take it that the strongest arguments for the two-concept claim are those just mooted, but that until we have considered them, for all that has been said so far, both the interdependence approach and the relational theory (which the two-concept claim would rule out) are still in the running for delivering an account of perceptual experience that shows that we can and do make sense of the location of consciousness in the natural world.