Lecture 2: Old style crises, booms and busts

advertisement

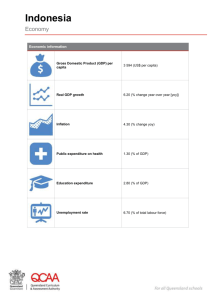

116103696 2/13/16 1 Lecture 2: Old style crises, booms and busts Overview of lect 2: Crises in the era before hot money 2.1 Oil price booms: effects of volatility in world markets * Moral #1: free trade may be good, but laisser-faire is not. * Moral #2: Spending on the poor is a great way to buy political quiescence, and is good for development too. 2.2 "Debt crisis" (Volker interest rate shocks) in the Philippines * Period of cheap and easy credit, followed by sudden tightening * Moral: cutting G. expenditure is not necessarily bad for the poor (Blejer and Guerrero). 2.1 The oil price booms (and busts) in Indonesia - In Lect 1 we noted possible tradeoff between NR wealth and industrial growth. = paradox: apparently poorly endowed E Asian countries have been best performers in terms of growth. - We also noted that it depends very much on how NR wealth is used. Burma has plenty and remains poor. Indonesia is example of NR wealth and rapid economic growth. Difference is mainly (not exclusively) in policies. - Tradeoff between NR wealth and long-run growth via industrialization is especially apparent during periods of rapid change, or “booms” and “busts” in NR exports. - OPEC-I (1973) period is excellent example, as are OPEC II and mid-80s oil price crash. - Oil shocks also illustrate points about costs and benefits of openness to international conomy. Oil price is highly volatile. - Oil price booms = terms of trade "shocks" (positive for exporters, neg. for importers). Indonesia = OPEC member, so gain. How was the windfall used? - Indo. price terms of trade increased sharply in 1973 and again late 1970s * NB Prices of imports, esp. food, rose in 1973 and this reduced ToT increase. * Income ToT also rose sharply; faster than PToT in 1970s. Figure: Indonesia's terms of trade 1960-90 (Booth: Oil boom and after Fig 1.2) 116103696 2/13/16 2 - Outcomes in 1970s set stage for Indonesian growth of 1980s-90s, so need to study closely for that reason; can also learn about FX of global shocks & role of policy responses. - Initial conditions: Indonesia poor, and (in about 1970) still struggling to emerge from chaos following Year(s) of Living Dangerously. - Political instability as New Order attempts to legitimize and move beyond events of 1966. - Poverty 40 – 50% of pop (dep. on measure). - Infant mortality (per thousand) = 132 average (urban 104, rural 137). - Only 22% pop. completed primary ed., another 10% had any kind of 2ndary or 3ary ed. - 2/3 labor force in agriculture earning wages near or below subsistence. - Ag. + mining > 53% of GDP; mfg < 10%. - OIL exports the main source of foreign exchange: receipts used to buy food and manufactures. 2.2 Impacts on growth and economic structure - Aggregate Income: 1st oil boom increased GDP by ~15%; second by ~ 20%. Figure: Annual percentage change in GDP (Booth Fig. 1.1) - Economic Structure - Pre-boom: Agriculture is biggest sector and main contributor to growth (more than 25% of growth from this sector) - mid-70s: agric. declined; its growth contributions lagged. * growth in Mfg, and in NT sectors: Pub admin; housing, transport, constr, utilities. 116103696 2/13/16 3 - Why? -- Examine effects of oil boom of (1) Agr. exports; (2) mfg; (3) nontraded goods. Indonesia: Sectoral breakdown of increment in real GDP, 1967-81. Percentage contribution to GDP growth: Sector 1973 GDP share 1967-73 1974-81 (%) Agriculture 40.1 27.4 16.4 Mining 12.3 12.9 4.4 Manufacturing 9.6 9.8 23.5 Construction 3.9 7.6 8.4 Transport 3.8 4.4 8.1 Public Admin. 6.0 3.6 13.2 All others 24.3 34.3 26.0 Total 100.0 100.0 100.0 Sources: Booth 1992: The Oil Boom and After, Table 1.5;Woo et al. 1994, Table 10.3 116103696 2/13/16 4 Adjustment mechanisms: - Even though the “boom” occurs only in one sector of the economy, its effects are felt in all sectors (1) Oil revenues are a large part of overall export receipts, so effect on exchange rate (if allowed to adjust): Decline of receipts from other tradable sectors (agric. exports; competing manufactures). (2) Spending of oil receipts in domestic economy has large effects on demand: Price increases for nontraded goods and services (for tradables, imports increase or exports decline but prices change by less). (3) Growth of NT sectors diminishes profitability in T sectors as input prices are bid up (e.g. of scarce factors such as capital and skilled labor). - Thus a positive shock – the oil revenue windfall – can have mixed effects on a poor economy. In some respects it has unambiguously negative effects: most importantly, the decline of manufacturing growth. Figure: Indonesian Manufacturing Growth and GDP shares (Booth 7.1) - In Fig 7.1: decline of mfg. after 1973, and again (precipitously) after 1979 (line 3-4) - But recoveries in late 1970s and in 1983. - Overall, GDP share of mfg (line 2) at least does not decline. - Fear of deindustrialization (Indonesia’s “other Dutch Disease”), with consequent long-term reduction in aggregate economic growth. 2.3 Policy responses: how did manufacturing and agr. sectors survive? - Fear of Dutch Disease motivated increased protection for import-competing manufacturing sector. - Early lessons (Pertamina scandal) taught value of prudence in managing forex windfalls (more later). 116103696 2/13/16 5 - Expectation that oil export revenues won't last for ever (Woo et al p.85) motivated investments in productivity growth through expenditures on education, health, rural & agr. development, etc. - These expenditures also had a political payoff. 1. Increase in protection: Indonesia: Effective protection for manufacturing sectors (percent) Type of tradable 1971 1975 All tradables 33 39.2 Exportables Importables Import-competing Noncompeting Woo et al Table 8.5 -11 65 66 15 -6.4 97.6 108.6 9.2 * However, these measures largely ineffective, since (a) tariffs were already high; (b) further increases led only to more smuggling. * Protections brings no benefit to non-oil exporters. 2. Sterilization of financial inflows by Central Bank, thus preventing "spending effect" from oil revenues. - Accumulation of foreign reserves as form of national saving. - Later (1983), devaluation to augment protection and increase competitiveness of non-oil exports. 3. Redirection of G. expenditures towards rural development, esp. "social infrastructure" - "Boom" in spending on education, housing and health - As share of G. investment, up from 12% in 1969-72 to 15% (1974-78) to 23% (1979-81); - Similarly, lge part of windfall spent in pub. inv. on agric. and fisheries. - These rates of increase matched only by spending on industry - Huge growth of public sector enterprises, some of which are only now (1998) being dismantled or privatized. 2.4 Distributional & welfare consequences of oil boom and responses * Q. What effects of boom on distribution of incomes? 116103696 2/13/16 6 - Initial public spending boom and protectionism for industry sheltered capitalists, urban industrial labor force, and public sector workers. - But agriculture sectors -- import competing (food) and exporting (rubber, spices, etc) initially penalized by: - Loss of competitiveness in international markets - Rising input costs due to mfg sector protection - Rural/agr. consumers hurt by inflation in N prices while ag. prices stayed low. - 1966: Indonesia has largest Communist party outside Comm. countries. Gov't political hold in 1973 is shaky -- depends on support in Outer Islands and rural Java -- mainly agricultural areas, and agro-exporters (e.g. Sulawesi-copra). - These areas clear losers from 1st oil boom—before any policy responses -Policy responses (esp. redirection of G expenditures to "social infrastructure") and subsequent devaluation clearly benefited outer islands, agriculture. - Result: Income distribution in Indonesia improved fairly steadily through oil boom period: Table: Decile exp. shares and Gini, 1970-87 (Woo et al 1994, Table 10.8) 2.5 Discussion: empirical lessons and theoretical insights Context of the Indonesian boom: Compare Indonesia with other oil exporters: better growth, less inflation, better use of pub. inv. - mainly sound macro management, especially inflation control. - More judicious protection and public investment to prevent deindustiztn and deagriciztn. Agricultural Output Per Capita, 1974-83 Country 1974-78 1979-81 1982-83 Algeria 89 83 70 Indonesia 109 123 127 Nigeria 91 91 84 Venezuela 104 102 101 Source: Woo et al., Table 10.15. - Economic and political payoffs from regional development, esp. in Outer Islands (present troubles notwithstanding!). 116103696 2/13/16 7 116103696 2/13/16 8 Lessons for management of open economies in SE Asia: the Pertamina Affair (Woo Ch. 7) - One of the earliest defaults on a short term loan by a major LDC corporation - Its crash reverberated thru Indon. Gov’t, requiring policies now known as “adjustment” - As such, precedes 1997 crisis by 22 years. - Background: - Nationalization of oil production in 1960 - Petamina formed as SOE in 1967, headed by Gen. Sutowo. - As oil production increased, and prices rose in 72-73, Pertamina became largest corporation in Asia outside Japan (7 wholly owned subsidiaries and 50+ joint ventures, domestically and internationally). - In addition to producing, refining, shipping and retailing oil, LNG & gasoline: - Fertilizer and chemicals production; manufacture of cement, equipment metals and metal products, steel, dry foodstuffs, rice plantations, etc. - Shipping and other trans. services; - Residential and commercial construction; road and hospital construction, etc. - Tourism and tourism promotion; insurance, etc…. - All financed out of oil revenues. The GOI had no way of knowing what these amounted to. Pertamina became an independent development agency and an indigenous zaibatsu, committed to economic nationalism, industrialism, and the supremacy of pribumi enterprises. - Meanwhile, as part of a post-1966 restructuring agreement with the IMF, GOI had committed to a cap of $14 mn in external borrowing for 1972-73. - Pertamina borrowed $350 mn. in that year without informing Min. of Finance. - Result: when discovered, US aid suspended; Pertamina agreed with GOI not to make any new loans with maturity 1-15 years. - Feb. 1975: in wake of OPEC I, world short-term interest rates rose. In the wake of several bank failures in US and Europe, Petamina was forced to pay higher interest rates on short-term debt and defaulted on a payment. It was later discovered to have accumulated $10 bn in outstanding credit, including $2.5 bn in short term debt (equiv. to 25% of total GOI budget). - Because Pertamina was (nominally) government owned, the GOI assumed responsibility for repayments. 116103696 2/13/16 9 - Doing so caused a big (though short lived) increase in the government budget deficit and a sharp reduction in investment; growth slowed by about 1/3 in the year following the crisis. - Thus the Pertamina scandal has all essential elements of subsequent Asian crises: * Overoptimism about future growth leading to lack of prudence in borrowing and lending (by both dom. and foreign agents) * Overcommitment in short-term, unsecured international debt markets * Lack of adequate regulatory control over borrowing and other business activities of corporations (whether state or private is almost irrelevant in SEA) * Corporate collapse necessary public sector adjustments – and ultimately a spreading of the burden to broad groups of those where were not responsible, not benefited from the earlier profligate spending. - Were lessons from Pertamina collapse learned in SE Asia? - In Indonesia, possibly: less of the need for sound macroecnomic management and fiscal prudence as components of a development strategy was clearly learned by New Order technocrats. - Unfortunately, this group had been largely replaced by mid-1990s: substantially by “technicians” (or “technologs”) such as Habibie, who held natoinalist development ideas similar to Sutowo and who had no experience of the post-Pertamina cleanup. - Elsewhere in SEA: no effect (same apt. bldg., but not communicating). 2.6 Indirect effects of booms and busts 1. Shocks are transmitted from one sector of the economy to another. -- Thus the oil boom, or similar, has impacts on other sectors through the labor and capital markets and through the spending of revenues from the boom on domestically produced goods and services. - Saw this in Indonesia’s “Dutch disease”. - Will see it in Thailand, where manufacturing growth directly reduces agricultural growth by drawing away rural labor. 2. Shocks are transmitted from capital markets (“financial shocks”) to the real economy through changes in investment. 116103696 2/13/16 10 -- the cost of capital to borrowers is affected by macroeconomic stability, which is a function of world market volatility and domestic government policies and institutions. -- Changes in the investment rate have direct and possibly long-term effects on growth. 3. When the government budget is affected by the need to adjust to a shock, the pattern of taxation and public sector spending and investment is altered. This will have economy-wide effects. -- E.g. Need to absorb private-sector losses (as in Pertamina scandal) may reduce G. development spending plans. -- Gov’t expenditures on social services – redistributive and anti-poverty programs included – may be affected by the need to adopt more austere policies. - We will see some of this in discussoins of the Thai and Indonesian crises. * Does cutting G. expenditure always have negative effects on the poor? Not necessarily. - Philippine economic crisis of mid-1980s provides an illustration. 116103696 2/13/16 11 Philippines, 1970s: “boom” led by public sector expenditures during period of cheap and easy credit (cp. “real” booms of oil shocks and later investment flows). - Use of public sector expenditures financed by international borrowing. - 11 "major industrial projects", etc. - Price controls on rice, corn, fuel, power, meat, cooking oil, etc. - Maintenance of ISI policies, esp. overvalued X rate. - Rapid growth of economy, employment, during expansionary phase. - But borrowing largely in short-term instruments at variable interest rates. - Spending was mainly “unwise” in a sense very similar to that of the Pertamina episode: motivated not by efficient use of resources, but desire to replace imports and develop “showcase” industries. - Employment impacts not very great as a result (mainly K-intensive) - Some costs for traditional produces, such as agricultural exportables and small scale manufacturers, as exchange rate overvaluation reduced competitiveness. - 1975-82: growing difficulties: CA deficit (% of GDP) doubles; External debt increases 5X; pub. sector deficit incr. to 7% of GDP. - Adjustment postponed by accomm. K inflow in 1970s * Crash and Stabilization, 1984-6: - Political and economic crisis, 1983 (Aquino assassination and maturation of short-term debt). - Investment collapse and drop in GNP growth rate to -7% - Peso devaluation - major reduction in P.S. deficit through tax increases and exp. cuts. * Because of nature of boom, esp. industries targeted and exchange rate overvaluation, the poor were not as negatively affected as might have been expected. the pattern of gov’t expenditure had been regressive; cuts thus helped to reduced inequality somewhat. - Of course, poverty rose tremendously.