Existentialism-Naipa..

advertisement

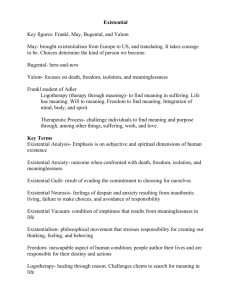

Pessimism and Existentialism in V. S. Naipaul Serafin Roldan-Santiago, University of Florida (Gainesville) The philosophic and thematic strands, along with the autobiographical strand in V. S. Naipaul, represent structures that deal directly with themes and ideas. They enrich the narratives with subtle meanings, thoughts and semantic direction. The autobiographical strand functions as a marker of personal identity since Naipaul has been in quest of "self" since the beginning. In the same manner, the philosophic strand has been essential in the development of a Naipaulian discourse. The philosophic strand is associated closely with the existential ideas of nothingness and dissolution, which in turn are closely connected to a state of pessimism and nihilism. This aura or existential sense is thus the idea or driving force that envelops many of his narratives. This is also true of Naipaulian irony. The philosophic notion of nothingness and dissolution has permeated most of Naipaul's writings beginning with his Trinidadian novels, especially The Middle Passage. This view has developed further in some of Naipaul's middle works such as Mr. Stone and the Knight's Companion, The Mimic Men, and In a Free State, and in his later works, A Bend in the River and The Enigma of Arrival. I prefer to call this a philosophic strand because the underlying currents and ideas can be classified as a variation of existentialist thought, perhaps post-1950s, that is, the ongoing existentialist thought to the present, especially as it pertains to post-coloniality. It is interesting to note that many postmodernist writings contain existentialist thoughts and perspectivees, perhaps as some critics have termed it, “neo-existentialism.” Certainly, it seems that existentialism in literature has extended its influence to our times, making it one of the major literary movements in the last hundred years. This philosophical idea of existentialism and its issues is a crucial semantic infrastructure in the Naipaulian complex. The philosophic strand gathers together ideas of existential pessimism, nothingness, dissolution and nihilism. There are various existential ideas that are connected with the philosophical pessimism discussed in this section. They are essential in order to understand better this Naipaulian form of existentialism.1 It would seem that Naipaul may be placed with some of the great existentialist writers of our times, such as Franz Kafka, Jean-Paul Sartre, Albert Camus and Ernest Hemingway. Among the major Naipaul texts, one can assuredly place The Mimic Men, In a Free 1 The terms are as follows: nothingness, panic, dissolution, destitution, dereliction, desolation, decay, doom, futility, nihilism, corruption, demise, abandonment. They are key terms associated with this existential pessimism. State, A Bend in the River and The Enigma of Arrival with these master texts.2 But even in his earlier texts one could notice a certain degree of this painful angst. The philosophic ideas of doom and futility were present and seasoned many of his earlier works. The strand is not only embedded in his fiction, but also envelops most of his travel texts, journalistic and autobiographical pieces. Most of Naipaul’s narratives contain this philosophic sense of futility and pessimism; many times characters are made to live the paradoxes of freedom, which represent a major issue in existentialist writings. Naipaul’s use of this strand entails a deep pathos about life that many times ends in panic. Again, the great Naipaulian panic is brought forth. There is the mood and idea of decay and all that it can gather: dissolution, futility, corruption and demise. It is a vision of the futility of life, especially in the post-colonial world. Lost post-colonials roaming across the post-colonial landscape, searching for a sense of identity, lost in a world that marginalizes them; their final destiny being desolation and dereliction. This Naipaulian philosophic strand projects the world as something that is constantly eroding and melting away. It constructs a deep pessimism about the world and its inhabitants who are represented as totally absorbed in futility. Man is striving to understand his existence, trying to grasp it and find its rationale, but is failing at it. It is as Doerksen has written when describing the search for meaning in life as, “…the futility of the search for the meaning of existence in both the past and the future” (108). It is important to point out that not only is this sense of futility and dissolution present in Naipaul’s fiction, but also embeds his travel literature and historical texts. Specifically, The Loss of El Dorado is certainly an existentialist history of the Caribbean where characters, plots and events are headed towards colonial dissolution and decay. It is not Naipaul’s bad intentions and meanness; it is the existential pessimism and nothingness, this driving, psychic force that permeates his writings. In 1987 Andrew Robinson interviewed Naipaul and asked him what his affinities to Indian thought and ideas were. Naipaul answered the following: "The philosophical aspect—Hindu I would say. Speculative and probably also pessimistic. What I mean by pessimism in not things turning out badly, but a pessimistic view about existence; that men just end. It is the feeling that life is an illusion. I've entered it more and more as I've got older" [my emphasis] (108). Thus, one can appreciate that subtle link to existentialist thought. refer to the two specific critical studies in existentialism in Naipaul’s writings by Nan Doerksen and T. Vijay Kumar. 2 In Naipaul’s writings there are images and terms utilized by early existentialist writers such as Jean Paul Sartre, Albert Camus, and Ernest Hemingway. Naipaul uses these terms, concepts, and images, the most important being the image of “nausea,” “nothing(ness),” and “panic.” All three form fundamental philosophical constructs in existential thought. Naipaul has articulated these in his own particular way. In Sartre's Nausea (1938), the protagonist Roquentin ponders the following about his existence: I glance around the room and a violent disgust floods me …With difficulty I chew a piece of bread which I can't make up my mind to swallow. People. You must love people. Men are admirable. I want to vomit - and suddenly, there it is: the Nausea.…So this is Nausea: this blinding evidence? I have scratched my head over it! I've written about it. Now I know: I exist - the world exists - and I know that the world exists. That's all. It makes no difference to me. It's strange that everything makes so little difference to me: it frightens me … (122-230) This quintessential passage is echoed in Naipaul's "One Out of Many" (In a Free State) by Santosh but in a different manner; the character is a post-colonial who has similar problems of existence. The words and the sense are so remarkably similar to those of Roquentin. Santosh declares: "I was once part of the flow, never thinking of myself as a presence. Then I looked in the mirror and decided to be free. All that my freedom has brought me is the knowledge that I have a face and have a body, that I must feed this body and clothe this body for a certain number of years. Then it will be over" (57-58). He has gained what Kumar calls “the freedom of an existential being,” with all of the uncomfortable feelings and ideas that this may entail (13). But all three narratives in In a Free State do not “solicit sympathy for a select few,” as Boxill has noted, “it concerns itself with all mankind, even the insane and the perverted; it does not try to pinpoint the oppressors of mankind. The enemy is not simply slavery or colonialism; it is life itself, mankind itself” (81). It is the existential condition of humanity, and for Naipaul, it is not a bed of roses. It is the existential angst in Santosh and Roquentin; the futility and the nothingness that gathers both of them into primordial existence. These disturbed sensations of the existential permeate many of Naipaul's writings. Sartre's "The Wall" is a story about political prisoners waiting for their execution at the time of the Spanish Civil War and the Franco regime. One of the characters, Tom, tells Pablo Ibbieta of the impending death that awaits them, something that will catch them off guard: "I've already stayed up a whole night waiting for something. But this isn't the same: this [death, mortality] will creep up behind us, Pablo, and we won't be able to prepare for it" (8). There is the sense of an ill feeling, a disturbing sensation, a nausea of the spirit, in these characters. Again, in Sartre's "Intimacy," the female protagonist, Lulu, is a disturbing character that provokes nausea in others. One is reminded of the many female characters in Naipaul that are presented in an unsavory manner such as Sandra in The Mimic Men, Linda in In a Free State, Jane in Guerrillas, Yvette in A Bend in the River, and finally, Willie’s females in Half a Life and Magic Seeds. These women are projected as nauseating figures, as characters that invoke nausea and a general malaise. The image of nausea is, undoubtedly, fundamental in Naipaul’s writings. Camus’ stories, “The Guest” and “The Growing Stone” forming part of the text, Exile and the Kingdom (1958), have similar philosophic underpinnings. Both stories deal with the philosophic angst of making decisions and choices, and how these can be interpreted as either betrayal or loyalty. In the first story the protagonist is Daru, a teacher stationed somewhere in a deserted region of Algeria, who has been placed in charge of an Arab who has committed homicide. Daru has the opportunity of setting his prisoner free; in fact, he tries to do so, but the Arab does not take his “hints.” It was difficult, or so it seemed for both protagonist and prisoner, to make a decision and choice, a decision that was connected intimately to freedom and being free. This furtive drama is brought forth. Daru has given the Arab the opportunity to escape, or so he thinks. But he does not set him free; he merely offers the prisoner an opportunity to escape. The Arab does not take it, and then voluntarily walks towards the East, towards his imprisonment. After having made this “bad faith” decision, Daru feels a general malaise in his body: “Daru felt something rise in his throat…swore with impatience, waved vaguely, and started off again” (108). One is reminded here of the decisions and choices that Michael X in Guerrillas, Singh in The Mimic Men, and Santosh in “One Out of Many” had to make or were trying to make, decisions which led them to the paradox of freedom, the existential ultimatum of every human being. In Camus’ second story, “The Growing Stone,” again the image of nausea is displayed. This story is set in the Brazilian jungle and the protagonist, D’Arrast, is a kind of consultant who is visiting these lonely outposts. He is also a character of exile. The poverty and ill conditions of the surroundings also provokes in him a malaise: “D’Arrast breathed in the smell of smoke and poverty that rose from the ground and choked him” (177). During his visit he encounters people in a religious dance in a village in which the participants become possessed with spirits. D’Arrast is upset at this and other primitive rituals. It is his existential reality that conflicts with the natives’. After participating involuntarily in the dance D’Arrast is shaken from his foundation: "The heat, the dust, the smoke of the cigars, the smell of bodies now made the air almost unbreathable. He looked for the cook, who had disappeared. D’Arrast let himself slide down along the wall and squatted, holding back his nausea" (195). Finally, the narrator informs us of D’Arrast’s loathing over this “whole continent,” and how it provokes nausea and a sense of nothingness: “The whole continent was emerging from the night, and loathing overcame D’Arrast. It seemed to him that he would have liked to spew forth this whole country, the melancholy of its vast expanses, the glaucous light of its forests, and the nocturnal lapping of its big deserted rivers” (198). Again, one is reminded of Santosh and Singh, and even of Salim in their situations and settings: the uneasiness, the plight, the futility of existence. These characters all reflect a kind of mental and spiritual, even philosophical, desolation and dereliction. It is one of Naipaul’s main concerns in his narratives. The philosophic term and concept of “nothing” and “nothingness” is also of importance in existential thought, especially in Naipaul’s particular strain. It is a term repeated many times in existentialist writings. In one of Hemingway’s best read stories, “A Clean, Well-Lighted Place,” the old waiter, who is a kind of alter-ego of the celebrated “old man,” offers the reader a soliloquy of exceptional existential nothingness: What did he fear? It was not fear or dread. It was a nothing that he knew too well. It was all a nothing and a man was nothing too. It was only that and light was all it needed and a certain cleanness and order. Some lived in it and never felt it but he knew it all was nada y pues nada y nada y pues nada. Our nada who art in nada, nada be thy name thy kingdom nada thy will be nada in nada as it is in nada. Give us this nada our daily nada and nada us our nada as we nada our nadas and nada us not into nada but deliver us from nada; pues nada. Hail nothing full of nothing, nothing is with thee. He smiled and stood before a bar with a shining steam pressure coffee machine. (382-83) It is almost another Roquentin meditation. The repetitious dirge towards nothingness and dissolution provokes a malaise and nauseating sense in the reader. It is a dictum that forces an individual into either making a decision of social or political commitment, or of dissolution into nothingness. One has to choose; it is one's responsibility to do so in this world. Ralph Singh in The Mimic Men is not merely informing the reader of a bad night, or even of his encounter with the fat prostitute, but rather, he is communicating his disgust toward his present condition: "In the hotel that night I was awakened by a sensation of sickness. As soon as I was in the bathroom I was sick: all the undigested food and drink of the previous day. My stomach felt strained; I was in some distress" (237). The image of nausea is invoked in this passage, but interestingly enough, this malaise has been with the protagonist since his exile, this sense of fear and dread about his existence. Santosh in "One Out of Many" also feels nausea while on the plane, but it is not just physiological nausea as the passage attests, it is also the "journey," as he states, "[T]he journey became miserable for me. … I had a shock when I saw my face in the mirror. In the fluorescent light it was the colour of a corpse" (25). The "journey" may be that of life and existence, and the "colour of a corpse" may well be the ultimatum of existence: nonexistence and mortality. Thus, one can see that the tenets of existential thought are embedded in both these narratives. Dayo's brother, the narrator in "Tell Me Who to Kill," is an estranged fellow, a tragic product of things gone wrong. He declares with great pain: "The funny taste is in my mouth, my old nausea, and I feel I would vomit if I swallow (100). Again, this is not merely a sample of a specific incident in the narrative but of the general feeling that sprinkles this text, a deep pessimism that envelops the whole discourse, an emptiness, a nothingness. Finally, in Naipaul's A Bend in the River the term, "nothing" is used many times. It is not just the mere word which is important, but its associative and connotative function. The narrator's first line reads: "The world is what it is; men who are nothing, who allow themselves to become nothing, have no place in it" (3). A casual reading of this first line would be useless; a close reading would bring out the hidden meanings and associations. The sentence is again one of the tenets of existential thought: one's existence is of value when one becomes involved and committed to society and the world. Individuals who are not involved are useless and become non-entities. They have become nothing of worth; they have allowed "themselves to become nothing." One final aspect of this existential angst in Naipaul that I would like to document and connect to this philosophical strand is the ever present "panic" that Naipaul has felt since his youth. He has referred to it as his "nerves," while at other times critics have called it "anxiety attacks." This "panic" has been documented in Naipaul's fiction and non-fiction. The panic appears in his early Trinidadian novels, which includes the black cloud incident in The Mystic Masseur and Biswas' panic while in Green Vale in A House for Mr Biswas. The last being more than just a mere "panic." It is the fear of becoming derelict or homeless, a fear that has been very close to Naipaul. It is the fight of an individual who does not want to end up in anonymity, who is fighting for an identity, and who many times ends up, as Naipaul terms it, a bogus. It is the philosophical theme of existential destitution in the contemporary post-colonial world. The "panic" continues in both his middle and later works; it is an ever present feeling of insecurity; the possibility of falling into a black hole of non-entity. Biswas in Green Vale felt like this: "He put his feet down and sat still, staring at the lamp, seeing nothing. The darkness filled his head.…He surrendered to the darkness" (267). Naipaul’s first short, lighthearted, and humorous narrative, Miguel Street, contains a light pessimism that would later develop into a devastating and utter darkness. There is a fatalism and futility in Elias trying to pass the sanitary inspector’s examination; in fact, he never did. Elias ironically enough landed as a cart driver collecting garbage. In the last section of Miguel Street, “How I Left Miguel Street” the narrator communicates a sadness in his short bitter remark, a sadness that will eventually turn into a sense of doom and futility in Naipaul’s later texts. The narrator comments: “I left them all and walked briskly towards the aeroplane, not looking back, looking only at my shadow before me, a dancing dwarf on the tarmac” (172). It was a foreboding of things to come. The references to the “black cloud” in The Mystic Masseur and its repeated use in A House for Mr. Biswas is connected to the existential panic in these characters: “… not the passing shock of momentary fear, but fear as a permanent state … (Mystic 123). It is in A House for Mr. Biswas where this strand can be first identified. In the narrative Mr Biswas was enveloped almost always in an atmosphere of insecurity. He had a constant fear of destitution and dereliction: “… a dot on the map of the world,” as he once remarked (237). This fear of becoming destitute is also part of Naipaul’s autobiographical parcel: there was this “fear” always around him as a man and writer: the vision of existential nothingness, decay and abandonment. For Naipaul, it is no joke; it is deadly serious. The following passage must be quoted in full because it exemplifies the existential consciousness of mortality felt by Mr Biswas. It was when a piece of tooth broke off from Mr Biswas’ mouth. The existential dread is quite pronounced. The passage reminds one of Sartre’s Roquentin and Santosh from “One Out of Many” in which both characters were conscious of parts of their bodies, and treated them as dislocated members of the whole. The narrator declares of Mr Biswas: Then biting his nails once evening, he broke off a piece of a tooth. He took the piece out of his mouth and placed it on his palm. It was yellow and quite dead, quite unimportant; he could hardly recognize it as part of a tooth: if it were dropped on the ground it would never be found: a part of himself that would never grow again. He thought he would keep it. Then he walked to the window and threw it out. (271) Mr Biswas’ sense of security as it seems was in the owning of a house. In his first but unsuccessful try, he had a small shack built in Green Vale, which was eventually burned down by the laborers. The narrator depicts a desperate situation in Mr Biswas’ life during his panic and nervous breakdown. The house is depicted in quite a decadent manner: “But Mr Biswas only muttered on the bed, and the rain and wind swept through the room with unnecessary strength and forced open the door to the drawingroom, wall-less, floorless, of the house Mr Biswas had built” (292). There is a great sense of futility and desperation in this scene. Later when Mr Biswas’ mother, Bipti, dies he goes to the wake and there are existential thoughts that go through his mind: “He was oppressed by a sense of loss: not of present loss, but of something missed in the past. He would have liked to be alone, to commune with this feeling. But time was short, and always there was the sight of Shama and the children, alien growths, alien affections, which fed on him and called him away from that part of him which yet remained purely himself, that part which had for long been submerged and was now to disappear” (480). There is an impending sense of doom and dissolution in this passage. Mr Biswas’ descent into maelstrom was made during the critical days at Green Vale where he was exposed to fear and panic of the most excruciating kind: “Fear seized him and hurt like a pain” (268). It was similar to the decay, dissolution and impending destruction contained in both of Edgar Alan Poe’s stories, “The Fall of the House of Usher” and “The Facts in the Case of M. Valdemar.” It is in The Middle Passage that Naipaul delves more fully into the existential plane of pessimism and dissolution. The text contains, for many critics, negative observations about the Caribbean in general, and yet, as I have mentioned before, it is not a sense of disgust towards the people and situations in the Caribbean that Naipaul wants to document. It is more of a philosophical assumption on the underlying premises of life in general. All the places that he visits are described and tinged with a malaise, a general perspective about life that invites one to reminisce about existential decay and ruins, about the nothingness and futility of life. Every place that he visits invokes one or more of these feelings. One of Naipaul's most timely statement has been misunderstood often because it is interpreted as a scathing and personal comment of disgust about his native region. But Naipaul's discourse should be analyzed, not in terms of binaries, but by taking into account sociological and historical realities. Let us look at the quote: "For nothing was created in the British West Indies, no civilization as in Spanish America, no great revolution as in Haiti or the American colonies. There were only plantations, prosperity, decline, neglect: the size of the islands called for nothing else" (27). If analyzed from the philosophical perspective, one would understand better Naipaul's existentialist discourse: the use of the word "nothing" is essential here and will lead us to a wider perspective of this passage and its meaning. Naipaul is not invoking a personal criticism, but a philosophical one. It is well known that the region was constructed for exploitation, plunder, rape and slavery; it was a giant sweatshop where people, materials and processes were placed in a giant cauldron from which a Caribbean degraded stew came forth. Thus, Naipaul's philosophical comment is timely and well taken. The Middle Passage is one of Naipaul's finest texts because, among other things, the reader is introduced to the complexities of Naipaul's philosophical schemes. One critic, Sybille Bedford, has interestingly characterized this philosophical sense in Middle Passage. She writes: "In form, the book is the account of what must have been on the whole a rather depressing Caribbean journey" [my emphasis] (1). No doubt, this "depressing" sense is one of the effects of this existential angst. At the end of his excursion to Surinam when he visits Coronie, Naipaul writes about his experience and utilizes concepts such as dereliction, desolation, and abandonment, which are terms that clearly describe and define his existential thinking: A derelict man in a derelict land…lost in a landscape which had never ceased to be unreal because the scene of an enforced and always temporary residence: the slaves kidnapped from one continent and abandoned on the unprofitable plantations of another, from which there could never more be escape. I was glad to leave Coronie, for, more than lazy Negroes, it held the full desolation that came to those who made the middle passage. (190) The Middle Passage thus represents Naipaul's introduction to the philosophical existentialist discourse, a way of writing that will follow him in his writing career: the search for self tinged with the sense of doom, demise and dereliction. MP is the beginning incursion into existential pessimism and nothingness, a preoccupation with existence and individuality, and the search for order and sanity in this world. Naipaul's Mr. Stone and the Knight's Companion is a small exquisite text that clearly projects a philosophical view, a perspective that reminds one of T. S. Eliot's Prufrock with its emphasis on decadence, demise and dissolution. Walter Allen in a trite, brief and superficial response to Naipaul's novel writes that the narrative "fails to satisfy," and calls it a "fable" that has failed (2). On the contrary there is a philosophical richness that surrounds this small text: the impending demise and dissolution of death that awaits us all, or as John Thieme has noted, "the fundamental existential problem of growing old."3 Thieme in the same article has also connected this short narrative to T. S. Eliot's The Waste Land, especially the section of "The Burial of the Dead" (503). Indeed, along with The Enigma of Arrival, a later text, which also touches upon these philosophical matters, MSK continues after The Middle Passage with the same exploration of the dread and decay of existence. It is with these two texts, The Middle Passage and Mr. Stone and the Knight's Companion that Naipaul will begin to traverse the philosophical landscapes of darkness and decadence in the post-colonial world. In MSK there is a feeling of loneliness, isolation and alienation; Mr. Stone carries with him a deep existential sadness and loneliness. He is slowly realizing the futility of life and impending death: "He stripped the city of all that was enduring and saw that all that was not flesh was of no importance to man. All that mattered was man's own frailty and corruptibility. The order of the universe, to which he had sought to ally himself, was not his order. So much he had seen before. But now he saw, too, that it was not by creation that man demonstrated his power and defied this hostile order, but by destruction" [the destruction of nature] (125). The question of existentiality is brought forth here. Mr. Stone is constantly trying to find order in his own existence, meaning in life, but it seems to be futile and meaningless: "…every racing week drew him nearer to retirement, inactivity, corruption…Every ordered week reminded him of failure…" (46). Everything that Mr. Stone thinks about is tinged with pessimism and decay; even the black cat reminds Mr. Stone of his demise and death: "You will soon be dead. Like me" (113). The contradictions and paradoxes of existence are made to bear: whether Mr. Stone wants to be alone, or whether he wants to have companionship. There is a paradox in this as the narrator informs us: "Certain things he lost. His solitude was one; never again would he return to an empty house" (33). One of the most important existentialist tenets has been faithfully rendered in the following passage as Mr. Stone ponders with deep philosophical inquisitiveness: "And he had a realization, too upsetting to be more than momentarily examined, that all that was solid and immutable and enduring about the world, all to which man linked himself…flattered only to deceive. For all that was not flesh was irrelevant to man, and all that 3 John Thieme, "Naipaul's English Fable: Mr. Stone and the Knights Companion," Modern Fiction Studies 30.3 (Autumn 1984), p. 499. was important was man's own flesh, his weakness and corruptibility" (42). Mr. Stone and the Knight's Companions, though a small text, carries with it a big philosophical punch of existential thought. It is another early display of Naipaul's later explorations of areas of darkness where nothingness and futility, destitution and dereliction, and the sense of doom and demise are passionately rendered. In An Area of Darkness, Naipaul's second travel narrative, there are continued descriptions and discussions of ruins; but this time, on the ruins of India. In this narrative India is viewed as a country littered with ruins and decadence in which destruction, annihilation, despair, and above all, dereliction, are everywhere to be felt. According to his thoughts, India is a land caught up in futility and destined to nothingness. Naipaul's philosophical attitude tinges everything that he sees; what he sees is an India that depresses his spirit. All creation in India hints at the imminence of interruption and destruction. Building is like an elemental urge, like the act of sex among the starved. It is building for the sake of building, creation for the sake of creation; and each creation is separate, a beginning and an end in itself….but at Mahabalipuram near Madras, on the waste sand of the sea shore, stands the abandoned Shore Temple, its carvings worn smooth after twelve centuries of rain and salt and wind….In India these endless mosques and rhetorical mausolea, these great palaces speak only of a personal plunder and a country with an infinite capacity for being plundered. (216-17) In the passage above one can notice the pessimistic sense that envelops his observations. It is a gloomy and dark, fatalistic vision of things: "India was part of the night: a dead world, a long journey" (279). In the first pages of this narrative Naipaul gives us a clue of what lay ahead. It was a slow and long journey into this Naipaulian area of darkness: It had been a slow journey, its impressions varied and superficial. But it had been a preparation for the East. After the bazaar of Cairo the bazaar of Karachi was no surprise; and bakshish was the same in both languages….From Athens to Bombay another idea of man had defined itself by degrees, a new type of authority and subservience. The physique of Europe had melted away first into that of Africa and then, through Semitic Arabia, into Aryan Asia. Men had been diminished and deformed; they begged and whined. Hysteria had been my reaction, and a brutality dictated by a new awareness of myself as a whole human being and a determination, touched with fear, to remain what I was. (15-16) In his last Indian travel narrative, India: A Million Mutinies Now, written twenty-six years later, Naipaul continues with this philosophical melancholy. In the first passage of "Breaking Out" there is this sense of futility and desperation. Naipaul refers to this experience in Goa as "the fracture in reality" (140). Naipaul also reminisces through his lens of pessimism of how he entered Calcutta in 1962: "My own days in Calcutta had been hard. When I had first come to Calcutta in 1962, I had, after the early days of strain, settled into the big-city life of the place; had had the feeling of being in a true metropolis, with the social and cultural stimulation of such a place. Something of that life was still there. But I was overpowered this time by my own wretchedness, the taste of the water, corrupting both coffee and tea as it corrupted food, by the brown smoke of cars and buses, by the dug-up roads and broken footpaths, by the dirt, by the crowds…" (346-47) Twenty-six years had elapsed and still, according to Naipaul, India was in a wretched and terrible condition. Another important philosophical narrative, The Mimic Men, is densely existential. Again, one can see the close relationship between this text and Mr. Stone: the confessional type of narrative that implicates philosophical moods. Both texts remind one of the Prufrock message with its deep sense of pathos and futility. Nazareth has also noted Naipaul's connection to T. S. Eliot in The Mimic Men (1970 xx). The protagonist and narrator, Ralph Singh, was not a bad fellow; he was humane and well educated; his intentions were not evil. But he was forced into corruption and exile by the same colonial system that he served, the paradoxical and lamentable ending, "a free and safe passage … " with his "sixty-six pounds of luggage and fifty thousand dollars" (24). The situation expresses quite an existential feeling. And again, one encounters the term, "nothing" when Singh reminisces in his lonely hotel room the paradox of existence: For here is order of a sort. But it is not mine. It goes beyond my dream. In a city already simplified to individual cells this order is a further simplification. It is rooted in nothing; it links to nothing. We talk of escaping to the simple life. But we do not mean what we say. It is from simplification such as this that we wish to escape, to return to a more elemental complexity. [my emphasis] (36)) Ralph Singh is well aware of the possibility of becoming destitute and forgotten, and he constantly struggles not to become derelict or homeless. The Mimic Men becomes a narrative of deep pathos and inquiry that explores lack of security, fear of rejection, loneliness (like Mr. Stone), alienation and demise. Singh's thoughts about life and its drabness are succinctly summarized in his own words: I have seen much snow. It never fails to enchant me, but I no longer think of it as my element. I no longer dream of ideal landscapes or seek to attach myself to them. All landscapes eventually turn to land, the gold of the imagination to the lead of the reality. I could not, like so many of my fellow exiles, live in a suburban semi-detached house.…[but prefer] the absence of responsibility; I like the feeling of impermanence… (10-11) Escape for the colonial politician is also viewed from a painful existential perspective. He is caught between the native people and the local politicians on one side, and the political world of Empire on the other; it is a futile affair, one that is highly ambiguous and ambivalent, a situation that many times degenerates into violence and corruption. For the colonial politician there is the tragedy of thinking that one has power: "The tragedy of power like mine is that there is no way down. There can only be extinction. Dust to dust; rags to rags; fear to fear" (40). Thieme has noted: "So no atonement is possible; all experience is tainted; all hopes of self renewal prove futile [my emphasis].4 Singh describes the tragedy of the colonial politician and his existence in the following manner: The career of the colonial politician is short and ends brutally. We lack order. Above all, we lack power, and we do not understand that we lack power. We mistake words and the acclamation of words for power; as soon as our bluff is called we are lost. Politics for us are a do-or-die, once-for-all charge. Once we are committed we fight more than political battles; we often fight quite literally for our lives. Our transitional or makeshift societies do not cushion us. There are no universities or City houses to refresh us and absorb us after the heat of battle. For those who lose, and nearly everyone in the end loses, there is only one course: flight. Flight to the greater disorder, the final emptiness: London and the home counties. [my emphasis] (8) 4 John Thieme, "A Hindu Castaway: Ralph Singh's Journey in The Mimic Men," Modern Fiction Studies, 30.3 (Autumn 1984), p. 513. The Mimic Men, though politically inclined, is nevertheless an extraordinary philosophical novel about man's existence and fate. But its fundamental framework is pessimistic and existentialist. As Nazareth has noted: "[It] is thus unremittingly pessimistic. Hardly anybody reveals any ideals, any values beyond grabbing what one can for oneself" (1970: 143). It is not just localized pessimism that is negotiated in this text, but rather, a deeper, more generalized, philosophic pessimism. The text continues to explore, as in The Middle Passage, these areas of philosophic darkness. John Hearne, another Caribbean writer, has written a well-crafted essay on Naipaul's The Mimic Men in which he underscores the most significant aspect of the narrative, i.e., its existential pessimism: "[It] is a good book with a despair so isolate, with a privacy so armoured against any intrusion of society, that we can do no more than concede the unremitting integrity of its pessimism" (31). The narrator and protagonist, Ralph Singh, reiterates: “nothing was secure.” There is an existential sadness behind the text, The Loss of El Dorado, but from a historical perspective. In The Loss, Naipaul gives us the impression that Trinidad has had a history of desolation and corruption. It is an island where things were never achieved, a place where things never settled down for the better. There was always instability and a sense of decay. Anarchy and nihilism seemed to be the common words to express everything that happened. Loss is a history, but it is a pessimistic history of decadence and degradation. This seems to be the basic underlying assumption of the text. As in many of his other texts, Loss contains irony threaded together with this philosophical strand of pessimism. It might seem that irony is just one other way, besides caricature, that Naipaul can utilize to deal with the existential stress of nothingness, a way by which this destitution and doom, this existential decay can be dealt with rhetorically. Corroborating my assumptions, Doerksen has noted the following about In a Free State: “it becomes clearly evident that it belongs in the genre of twentieth-century existentialist writings” (105). Kazin characterizes it's theme as "the tenuousness of man's hold on the earth" (3). In a Free State consists of three short narratives, each independent from the other but thematically linked, and two outer flaps, a prologue and an epilogue that seems to bind them together. But all five pieces are intimately connected to the existential angst of the paradox of freedom and being. The constant references to nausea and nothingness have already been discussed in relation to this text. But now we are introduced to the freedom of an existential being and all the contradictions that this involves in Santosh, in Dayo's brother, in Bobby and Linda, and even in the narrator himself and the tramp. All these characters are experimenting with freedom and its paradoxes. According to Boxill, “Naipaul ends by suggesting that in this world no time has ever been pure and consequently, absolute freedom can never exist. Purity and freedom are fabrications, illusions, causes for yearning, things for the tomb” (91). The mad narrator in “Tell Me Who to Kill” groans with great existential pain: “Let the rat come out. The lie is over. I am like a man who is giving up. I come with nothing. I have nothing, I will leave with nothing” [my emphasis] (96). Santosh in “One Out of Many” tells us: "All that my freedom has brought me is the knowledge that I have a face and have a body, that I must feed this body and clothe this body for a certain number of years. Then it will be over" (57-58). For Dayo's brother and Santosh there is no purpose in life but the final dissolution and demise. In the story, “In a Free State,” Bobby and Linda are caught up in a sense of dread, alienation and horror: a sense of insecurity permeates this longer narrative; the same panic and fear that are present in A Bend in the River. The Conradian nature of Bend suggests as Walder has noted, "an inevitable cycle of corruption, arising out of the darkness within humanity" (108). Even though this text, like his other texts, deals mostly with the post-colonial condition of man, Naipaul's intent is to display more fully the universal dilemma of man and his existential condition. And he underscores this with a sense of dread in which the conclusion tends to be less of a happy ending and more of an ultimate decay and dissolution of man. The existential sense of disgust and nausea is also brought out in Guerrillas when Roche is conversing with Mrs. Stephens about life in general and how things can go wrong. The use of nausea is utilized in the following passage. But it is not just a description of a physical discomfort or part of the local scene that is narrated; it is a more universal feeling of disgust. It is a projection of decay and non-being. But he wasn't prepared for the contempt, the contempt of women for women, the contempt which, in that room, from Mrs. Stephens, was like a contempt for her own body and the body of her neighbor, slack, swollen, worn out. The grapefruit taste in Roche's mouth went bitter; he associated it with the smell of the chicken dung and dust that came through the window; and the saliva thickened nauseously on his tongue. (107) Roche after his interview with Meredith in the studio becomes sad and overwhelmed due to the failure of the encounter. It seems he has had it with Trinidad; everything has come out wrong and nasty. He is a cuckold and a failure. But more than this there is the loneliness that he feels of the "immense world"; the sense of nothingness and disarray. A great exhausted melancholy came to Roche: the sense of the end of the day [or his life], a feeling of futility, of being physically lost in an immense world. Melancholy, at the same time, for the others, more rooted than himself: for the studio manager, the man from the country, for the policeman with the rifle and the woman at the desk who were both so deferential to Meredith, melancholy for Meredith: an overwhelming exasperation, almost like contempt, confused with a sense of the fragility of their world. [my emphasis] (210) A Bend in the River and In a Free State are novels with a deep Conradian pathos that reflect worlds falling apart. They are books that have an African setting and deal with alienation and fluctuating identities in the post-colonial world where tragic figures, marginalized and frustrated, grope for a sense of identity and meaning in life. There is an extreme pessimism projected by Naipaul in both these texts as to possible changes in Africa. This is also true of Naipaul's Indian texts and his Islamic ventures; it is not a personal form of criticism, but one that seems to unveil a great post-colonial conspiracy against the Third World. It is not what Empire has done to its peripheries, but what has not been done after the rampage, the pillage and the exploitation. The Third World has been ravished and left destitute by Empire: it has not been provided with support for its future development. It is this bitter consequence, which for Naipaul has no immediate answers but futility, dissolution and disintegration.5 The African rage that is characterized in the following passage is not something that is strictly local and African. Naipaul has used this same primitive rage in his other texts to characterize a more existential nihilism that humans by nature have within themselves. Salim tries to describe this nihilism: "The wish had only been to get rid of the old, to wipe out the memory of the intruder. It was unnerving, the depth of that African rage, the wish to destroy, regardless of the consequences" (26). This African rage, this nihilism, is something that is also fundamentally human regardless of where it takes place, whether in Africa, South Asia, South America, North America, or in the Caribbean. The following passage in ABR that characterizes 5 See John Kuar Persaud Ramphal. "V. S. Naipaul's Vision of Third World Countries" Thesis. York U, 1989. this nihilism is emblematic of the twentieth century in general where ideologies and beliefs have fostered massacres and genocides in the name of justice and equality: Now they say they have to do a lot more killing, and everybody will have to dip their hands in the blood. They're going to kill everybody who can read and write, everybody who ever put on a jacket and tie, everybody who put on a jacket de boy. They're going to kill all the masters and all the servants. When they're finished nobody will know there was a place like this here. They're going to kill and kill. They say it is the only way, to go back to the beginning before it's too late. The killing will last for days. They say it is better to kill for days than to die forever. It is going to be terrible when the President comes. (275) Salim begins this narrative by laying a fundamental existential assumption that is the conceptual framework of the entire novel. It is not just a simple credo or assumption, as Campbell has wanted to argue (399), but rather, it is a declaration that has universal sense, a universal credo of man's existence and his futile search for meaning and identity: “The world is what it is; men who are nothing, who allow themselves to become nothing, have no place in it" (3). In "A New King for the Congo," part of The Return of Eva Peron, with the Killings in Trinidad, the non-fiction piece written before Bend and directly connected to it, Naipaul again indulges in "African nihilism," that is, "a wish to wipe out and undo" modern civilization from Africa. All the terms I have utilized such as dissolution, destitution, doom, corruption, are gathered in this term. Interestingly enough, this is also Naipaul's issue in his Indian and Islamic narratives: the undoing of intellectual, philosophical, and historical progress at the expense of superstition and traditional ignorance. As Naipaul writes: "Because their resentments….can at any time be converted into a wish to wipe out and undo, an African nihilism, the rage of primitive men coming to themselves and finding that they have been fooled and affronted" (195). It is quite a pessimistic view, a scenario of futility, a world that feeds on nihilism and decay, where no clear path is in view. This vision was also transferred to A Bend in the River, the fictional counterpart of this travel narrative. In Among the Believers Naipaul describes rag-pickers and garbage collectors (“…sift[ing] through the garbage for everything that could be sold…”) as wretched people who were living at the very bottom of society. In his description one can sense the pessimism that envelops these passages; the possibilities of dereliction and destitution. As Naipaul noted: “things could easily go wrong” in this kind of society. They were the men who became rag-pickers. They were the men who could be seen picking up cigarette butts (but using two long bamboo sticks like long chopsticks) to sell the tobacco for a kind of cigarette for the poor. They were the lost people of Java, and some of them were even without “papers.” They were the people squeezed out by the fertility of Java from the civilization of Java, people at the very bottom who had lost their personalities as much as Darma-sastro’s people at the top. With their baskets on their backs, their long sticks, their minutes diligence, their eyes forever on the ground, like people withdrawn from the bustle and the crowds, they were a warning to everybody else …” (360-61) In the section “Islamic Winter” Naipaul relates a dreadful story. It is the sad story of the deranged, totally alienated, young boy in Tehran. It is a horror story about destitution. It envelops our minds with an existential fear and panic of what might very well happen to us; it is something so very close to Naipaul as he writes: “It was frightening to me, too” (142). …a small boy sat on the pavement not far from plastic sacks of store rubbish. He had lit a fire in the middle of the pavement, using rubbish from the sacks….The boy, who was about ten, sat right up against his fire. But he wasn’t warming himself. With a face of rage, he was tearing at his shirt; and he was already half naked from the waist up. It was very cold; there was a wind. The boy, sitting almost in his fire, with two boxes of matches beside him, tore and tore at his shirt. His bare feet were grimy; his face was grimy. People stopped to talk to him; he looked up –staring eyes in a soft, well-made face – and continued to tear at his shirt….The hysteria of this child, stretched to breaking point, would have matched the mood of many of the passersby; and was too frightening. (424) In Beyond Belief, a narrative of his Islamic ventures seventeen years later, Naipaul continues with this deep sense of pessimism towards these “converted people” and their existence. Naipaul observes in this text a state of insecurity in the various countries he visits. It develops into philosophical nihilism; the Islamic state has entered every facet of people’s lives. There is no sense of escape; these “converted” people have had their history erased. Naipaul’s deep pessimism is everywhere inscribed, and by the end of the text one has a panic to deal with. It is a book of many stories that lead to futility and resignation; stories that may very well have a prophetic sense of upcoming doom and destruction, like the story of the deformed abused housewife who had her nose butchered by her husband. She was unable to do anything to defend herself; it was a futile affair; “she was helpless” (254). In "Author's Foreword" (Finding the Center), Naipaul informs us of the importance of finding order and a center in one's experience of the world, of identifying the incongruities of human existence so that one can understand and make sense of them. He writes the following of his West African trip: "…the people I found, the people I was attracted to, were not unlike myself. They too were trying to find order in their world, looking for the center; and my discovery of these people is as much part of the story…" (ix). Most of the people and individuals represented in this and other texts are existential beings that will never obtain the serenity, assurance and order that they seek. They are destined to failure according to Naipaulian discourse. The Enigma of Arrival, a massive text that includes an immersion into autobiographical realities, is also a philosophical text in which Naipaul projects existential ideas of impermanence, futility, and doom. Naipaul's panic, associated with this philosophical strand, is documented many times. Again, let me utilize the same quote that I used elsewhere in this study, but this time focusing on the philosophical idea that this strand takes on in Naipual: "To see the possibility, the certainty, of ruin, even at the moment of creation: it was my temperament. Those nerves had been given me as a child in Trinidad partly by our family circumstances: the half-ruined or broken-down houses we live in, our many moves, our general uncertainty" (52). These "nerves" and sense of panic are certainly connected to this philosophical perspective of doom and dissolution. At one point this existentialist credo is characterized plainly through Jack, the gardener, as Naipaul writes: "The bravest and most religious thing about his life was his way of dying: the way he had asserted, at the every end, the primacy not what was beyond life, but life itself" (93). It is clear that existentialist thought is not interested in what is "beyond life," but in life itself as was illustrated in Sartre's "The Wall." The Enigma of Arrival is a text that takes major concerns with autobiographical realities and philosophical implications; it is a book in which Naipaul is defining himself more fully, it is a sensitive, introspective, meditative and sincere text of himself. The following passage clearly reflects Naipaul's thoughts, a way of looking at everything from the perspective of decay: How sad it was to lose that sense of width and space! It caused me pain. But already I had grown to live with the idea that things changed; already I lived with the idea of decay. (I had always lived with this idea. It was like my curse: the idea, which I had had even as a child in Trinidad, that I had come into a world past its peak.) Already I lived with the idea of death, the idea, impossible for a young person to possess, to hold in his heart, that one's time on earth, one's life, was a short thing. These ideas, of a world in decay, a world subject to constant change, and of the shortness of human life, made many things bearable. (23) The existential sadness continues in a later travel narrative, A Turn in the South, which takes Naipaul on a trip through the Southeast portion of the United States. The characters involved in this text also have a historical sense of hopelessness: the poor whites, the Blacks, the people on the bottom. This melancholic sadness, this song of the South, is a bleak foreshadowing for these groups. There is a deep sense of pathos and futility, especially as it pertains to the Southern Blacks and their plight. Though they have been liberated from slavery, they are still a rejected people and as Naipaul has noted: "among the most denuded in that country" (119). The same sadness and futility that was present in The Loss is also present here. This sense of historical doom and existential decay continues in A Way in the World. In A Way, Naipaul again documents his pessimism, both from a historical perspective as in The Loss of El Dorado and from a synchronic view as in The Middle Passage. There are also many autobiographical sections and passages in which philosophical pessimism is present. In broad terms A Way represents a text that is tinged with an atmosphere of insecurity, panic and destitution. Naipaul's description of the inside of the Registrar-General's department with its fish glue smell gives a slight impression of a nauseating stimulus: "The volumes smelled of fish glue. This was what they were bound with; and I suppose the glue was made from a boiling down of fish bones and skin and offal. It was the colour of honey; it dried very hard, and every careless golden drip had the clarity of glass; but it never lost the smell of fish and rottenness" (23). The text includes such sections as "New Clothes: An Unwritten Story," which represent illusions and possibilities, a "what if" situation for the writer. It is a section in which futility is clothed with anonymity. The story reminds one of Camus' "The Growing Stone" (Exile and the Kingdom) in which the principal character has similar traits and existential feelings as this anonymous character in "unwritten story." "New Clothes" is another strange story, a kind of post-modernistic narrative in which the narrator is implicated in, not only the story, but in the writing of the story, looking into the mirror of a mirror. The illusion continues. The narrator narrates about this other narrator as he sinks into the red water (from the leaves), and a discourse of nothingness ensues much in the same manner as in Hemingway and Sartre's texts. The pool is as deep as the young men say. Soon the light fades from the water. Soon it is utterly black. Soon it is of a black so deep that it is without colour: it is nothing, however much you concentrate on it. In this nothing the narrator feels he has lost touch with his body; water blocks sensation. He is just his eyes concentrating on nothing; he is just mind alone, a perceiving of nothing. He is quite frightened. He somehow gets in touch with his will again and pulls himself up, to the yellowing light. (65). Raleigh and Miranda are characterized as tragic figures, lost in swamps of desperation in the New World, becoming almost destitute at times. Total pessimism envelops their actions; they are caught between Empire and the uncivilized New World. They are futile characters in a futile environment according to Naipaul. This is also true of the real-life based characters of Lebrun, Morris and Blair: losers of everything, and caught in the currents of the New World vortices of demise, doom and decay. Finally, one should look at Miranda and Sally's letters. These missives reflect such a sad existential and futile mood, intimate and pathetic conversations that project a kind of madness and the eventual arrival of "nothingness" in their lives (299-334). Truly, Naipaul’s areas of darkness are not only physical and material in nature, but begin in the deep recesses of the spirit of man; a sense of dread about life and what the future may hold. It is an existentialist mind trying to grope for sanity and order in a world that is governed by apparent chaos and death, in a world that is filled with contradictions and paradoxes. Serafin Roldan, Ph.D. April 15, 2006, rev. 11/2007 Works Cited Primary : V. S. Naipaul Naipaul, V. S. Among the Believers: An Islamic Journey. 1981. New York: Vintage, 1982. ---. An Area of Darkness. 1964. New York: Macmillan, 1965. ---. A Bend in the River. 1979. New York: Vintage International, 1989. ---. Beyond Belief: Islamic Excursions Among the Converted Peoples. 1998. New York: Vintage International, 1999. ---. The Enigma of Arrival. 1987. New York: Vintage, 1988. ---. Finding the Center: Two Narratives. 1984. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1984. ---. Guerrillas. 1975. New York: Vintage International, 1990. ---. Half a Life. 2001. New York: Vintage International, 2002. ---. A House for Mr Biswas. 1961. London: Penguin, 1992. ---. In a Free State. 1971. Middlesex: Penguin, 1973. ---. India: A Million Mutinies Now. 1990. London: Viking Penguin, 1991. ---. The Loss of El Dorado. 1969. Middlesex: Penguin, 1973. ---. Magic Seeds. 2004. New York: Alfred Knopf, 2004. ---. The Middle Passage. 1962. New York: Vintage, 1981. ---. Miguel Street. 1959. London: Heinemann, 1974. ---. The Mimic Men. 1967. Middlesex: Penguin, 1969. ---. Mr Stone and the Knights Companion. 1963. Middlesex: Penguin, 1973. ---. The Mystic Masseur. 1957. London: Heinemann, 1971. ---. A Turn in the South. 1989. New York: Vintage International, 1990. ---. A Way in the World. 1995. New York: Vintage International, 1995. Primary : General Camus, Albert. Exile and the Kingdom. 1957. New York: Vintage, 1991. Conrad, Joseph. Heart of Darkness. 1902. New York: Norton, 1971. Hemingway, Ernest. The Short Stories. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1995. Phillips, Caryl. The European Tribe. New York: Farrar, Straus, Giroux, 1987. Poe, Edgar Allan. The Complete Tales and Poems. New York: Barnes & Noble, 1992. Sartre, Jean-Paul. Nausea . 1938. New York: New Directions, 1964. ---. The Wall, and Other Stories. New York: New Directions, 1948. Secondary : Criticism Allen, Walter. "London Again." The New York Review of Books 2.3 (1964): 1-6. Anderson, Linda R. "Ideas of Identity and Freedom in V.S. Naipaul and Joseph Conrad." English Studies 59 (1978): 510-17. Barloewen, Constantin von. "Naipaul's World." World Press Review Apr. 1985: 32-33. Bedford, Sybille. "Stoic Traveler." The New York Review of Books 1.6 (1963): 1-5. Berger, Roger A. "Writing Without a Future: Colonial Nostalgia in V. S. Naipaul's A Bend in the River." Essays in Literature 22.1 (1995): 144-56. Boxhill, Anthony. "The Paradox of Freedom: V.S. Naipaul's In a Free State." Critique: Studies in Modern Fiction 18.1 (1976): 81-91. Boyers, Robert. "Confronting the Present." Salmagundi 54 (1981): 77-97. Brown, John L. "V. S. Naipaul: A Wager on the Triumph of Darkness." World Literature Today 57.2 (1983): 223-27. Brunton, Roseanne. "The Death Motif in V. S. Naipaul's The Enigma of Arrival: The Fusion of Autobiography and Novel As the Enigma of Life-and-Death." World Literature Written in English 29.2 (1989): 69-82. Calder, Angus. "Darkest Naipaulia." New Statesman 8 Oct. 1971: 482-83. Campbell, Elaine. "A Refinement of Rage: V.S. Naipaul's A Bend in the River." World Literature Written in English 18 (1979): 394-406. Conversations with V. S. Naipaul. ed. Feroza Jussawalla. Jackson, MS: UP of Mississippi, 1997. Dayan, Joan. "Gothic Naipaul." Transitions 59 (1993): 158-70. Dissanayake, Wimal, and Carmen Wickramagamage. Self and Colonial Desire: Travel Writings of V. S. Naipaul. New York: Peter Lang, 1993. Doerksen, Nan. "In a Free State and Nausea." World Literature Written in English 20.1 (1981): 105-13. Duyck, Rudy. "V. S. Naipaul's Heart of Darkness." ACLALS Bulletin 7.4 (1986): 86-94. Erapu, Leban. "V.S. Naipaul's In a Free State." Bulletin of the Association for Commonwealth Literature and Language Studies 9 (1972): 66-85. Gourevitch, Philip. "Naipaul's World." Commentary 98.2 (1994): 27-31. Gurr, Andrew. "The Freedom of Exile in Naipaul and Doris Lessing." Ariel 13.4 (1982): 7-18. Hayward, Helen. The Enigman of V. S. Naipaul: Sources and Contexts. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2002. Hearne, John. "The Snow Virgin: An Inquiry into V. S. Naipaul's Mimic Men." Caribbean Quarterly 23.2-3 (1977): 31-37. Howe, Irving. "A Dark Vision." New York Times Book Review 13 May 1979: 1+. Kabat, Geoffrey. "Historical Disorder and Narrative Order in Naipaul's The Mimic Men." Commonwealth Novel in English 9-10 (2001): 208-17. Kakutani, Michiko. "Dreams of Glory Unraveling in Chaos." New York Times 30 Nov. 2004. 15 Feb. 2004 <http://www.nytimes.com>. Kazin, Alfred. "Displaced Person." Rev. of In a Free State, by V. S. Naipaul. The New York Review of Books 30 Dec. 1971. 8 Mar. 2004 <http://www.nybooks.com/articles/10340>. King, Bruce. V. S. Naipaul. Basingstoke: Macmillan, 2003. Kortenaar, Neil ten. "Writers and Readers, the Written and the Read: V. S. Naipaul and Guerrillas." Contemporary Literature 31.3 (1990): 324-34. Kumar, T. Vijay. "Being, Nothingness, and the Paradox of Freedom: A Study of V. S. Naipaul's 'One out of Many'." The Literary Endeavour 4.3-4 (1984): 8-14. Labaune Demeule, Florence. "De Chirico Revisited: The Enigma of Creation in V. S. Naipaul's The Enignma of Arrival." Commonwealth Essays and Studies 22.2 (2000): 107-18. Lane, M. Travis. "The Casualties of Freedom: V.S. Naipaul's In a Free State." World Literature Written in English 12 (1973): 106-10. Langran, Phillip. "V. S. Naipaul: A Question of Detachment." Journal of Commonwealth Literature 25.1 (1990): 132-41. Levy, Judith. V. S. Naipaul: Displacement and Autobiography. New York: Garland, 1995. Meaney, Thomas. "Exile's Return." Commentary 119.3 (2005): 82-84. Michener, Charles. "The Dark Visions of V. S. Naipaul." Newsweek 16 Nov. 1981: 104-11. Mishra, Vijay. "Lives in Halves: A Homage to Vidiadhar Naipaul." Meanjin 61.1 (2002): 123-26. ---. "Mythic Fabulation: Naipaul's India." New Literature Review 4 (1978): 59-65. Mustafa, Fawzia. V. S. Naipaul. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1995. Nazareth, Peter. "The Mimic Men As a Study of Corruption." East Africa Journal 7.7 (1970): 1822. ---. "Out of Darkness: Conrad and Other Third World Writers." Conradiana 14.3 (1982): 173-87. Nightingale, Margaret. " George Lamming and V. S. Naipaul: Thesis and Antithesis." ACLALS Bulletin 5.3 (1980): 40-50. ---. "V. S. Naipaul As Historian: Combating Chaos." Southern Review: Literary and Interdisciplinary Essays 13.3 (1980): 239-50. ---. "V.S. Naipaul's Journalism: To Impose a Vision." New Literature Review 7 (1979): 53-65. Noel, Jesse A. "Historicity and Homelessness in Naipaul." Caribbean Studies 11 (1972): 83-87. Ormerod, David. "In a Derelict Land: The Novels of V. S. Naipaul." Wisconsin Studies in Contemporary Literature 9 (1968): 74-90. Prescott, Lynda. "Past and Present Darkness: Sources for V. S. Naipaul's A Bend in the River." Modern Fiction Studies 30.3 (1984): 547-59. Rampersad, Arnold. "V. S. Naipaul: Turning in the South." Raritan: A Quarterly Review 10.1 (1990): 24-47. Ramphal, John Kuar Persaud. V. S. Naipaul's Vision of Third World Countries. Diss. York U, 1989. Ann Arbor: UMI, 1990. Roldan-Santiago, Serafin. "V. S. Naipaul's Vulcanization of Travel and Fiction Paradigms." The Atlantic Literary Review 2.3 (2001): 143-73. Schiff, Stephen. "The Ultimate Exile." The New Yorker May 1994: 60-71. Sheppard, R. Z. "Literary Platypus." Time 30 May 1994: 64. ---. "Notes From the Fourth World." Time 21 May 1979: 89-90. ---. "Wanderer of Endless Curiosity." Time 10 July 1989: 58-60. Subramani, Shankar. "Historical Consciousness in V. S. Naipaul." New Literature Review 15 (1988): 21-32. Thieme, John. "A Hindu Castaway: Ralph Singh's Journey in The Mimic Men." Modern Fiction Studies 30.3 (1984): 505-18. ---. "Naipaul's English Fable: Mr Stone and the Knights Companion." Modern Fiction Studies 30.3 (1984): 497-503. ---. "Naipaul's Third World: A Not So Free State." The Journal of Commonwealth Literature 10.1 (1975): 10-22. Walder, Dennis. "'How Is It Going, Mr. Naipaul?': Identity, Memory and the Ethics of PostColonial Literature." Journal of Commonwealth Literature 38.3 (2003): 5-18. Walder, Dennis. "V. S. Naipaul and the Postcolonial Order: Reading In a Free State." In Recasting the World: Writing After Colonialism . Ed. Jonathan White. Baltimore: John Hopkings UP, 1993. Walker, W. John. "Unsettling the Sign: V . S. Naipaul's The Enigma of Arrival." Journal of Commonwealth Literature 32.2 (1997): 67-85. Weiss, Timothy. "Invisible Forces of the Postcolonial World: A Reading of Naipaul's 'Tell Me Who to Kill'." Journal of the Short Story in English 26 (1996): 94-103. ---. On the Margins: the Art of Exile in V.S. Naipaul. Amherst, MA: U of Massachusetts P, 1992. ---. "V. S. Naipaul's 'Fin de Siècle': The Enigma of Arrival and A Way in the World." Ariel: A Review of International English Literature 27.3 (1996): 107-24. Wright, Derek. "Autonomy and Autocracy in V. S. Naipaul's In a Free State." International Fiction Review 25.1-2 (1998): 63-70. Wyndham, Francis. "V. S. Naipaul." The Listener 7 Oct. 1971: 461-62.