Dzwairo

advertisement

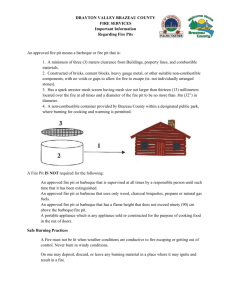

ASSESSMENT OF THE IMPACTS OF PIT LATRINES ON GROUNDWATER QUALITY IN RURAL AREAS: A CASE STUDY FROM MARONDERA DISTRICT, ZIMBABWE *B.Dzwairoa, Z.Hokoa, D.Loveb,c, E.Guzhad a Civil Engineering Department, University of Zimbabwe hoko@eng.uz.ac.zw, b Geology Department, University of Zimbabwe davidlove@science.uz.ac.zw, c WaterNet, Zimbabwe davidlove@science.uz.ac.zw, d Mvuramanzi Trust, Zimbabwe eguzha@zol.co.zw *Corresponding author. Box MP 167, MT Pleasant, Harare, Zimbabwe Tel.: +263 4 303288; fax: +263 4 303288 dzvairo@eng.uz.ac.zw/ bdzvairo@excite.com ABSTRACT In resource-poor and low-population-density areas, on-site sanitation is preferred to off-site sanitation. However, its groundwater pollution potential in such areas conflicts with IWRM principles that advocate for sustainability of water resources in terms of both quality and quantity. Given the widespread use of shallow groundwater for domestic purposes in rural areas, maintaining groundwater quality is a critical livelihood intervention. This study assessed impacts of pit latrines on groundwater quality in Kamangira Village, Marondera District, Zimbabwe. Groundwater samples from 14 monitoring boreholes and 3 shallow-wells were analysed during 6 sampling campaigns, between February 2005 and May 2005. Parameters analysed were total and faecal coliforms, NH3-N, NO2--N, NO3--N, conductivity, turbidity and pH, both for boreholes and shallow-wells. Total and faecal coliforms both ranged 0-TNTC (too-numerous-to-count), 78% of results meeting the 0 CFU/100 ml WHO 1 guidelines value. NH3-N ranged 0-2.0mg/l, with 99% of results falling below 1.5mg/l WHO recommended value. NO2--N and NO3--N ranged 0.0-0.64 and 0.0-6.7mg/l, within 3 and 10mg/l WHO guidelines values, respectively. Conductivity ranged 46-370s/cm while pH ranged 6.87.9. There are no guideline values for these parameters. Turbidity ranged 1-45NTU, 59% of results meeting the 5NTU WHO guidelines limit. Water table seasonal-drop averaged 1.1-1.9m. Soil from monitoring boreholes was characterised as sandy. The soil infiltration layer averaged 1.3-1.7m above water table for two latrines and 2-3.2m below it for one. A survey revealed the prevalence of diarrhoea and the unsuitability of pit latrines due to structural failure. Results indicated that pit latrines were microbiologically impacting on groundwater quality up to 25m distance, raising fears of exposure to pathogens associated with coliforms. Nitrogen values were of no immediate threat to health. The shallow water table increased pollution potential from pit latrines. Raised pit latrines and other low-cost technologies could be considered to minimize potential of groundwater pollution. Keywords: groundwater quality, pit latrines, rural area, sustainable sanitation 2 1. INTRODUCTION Worldwide, water-borne diseases are a major cause of morbidity and mortality in humans (WHO, 1996). While water-borne pathogens infect around 250 million people per year, resulting in 10-20 million deaths (Anon, 1996), many of these infections occur in developing nations that have sanitation problems (Nsubuga et al., 2004). Lewis et al. (1980) also reiterates that diseases caused by pathogens and related to the use of contaminated groundwater, are the greatest cause of death in developing countries. In countries such as Zimbabwe and South Africa, most of the rural communities are poverty-stricken, lack access to portable water supplies and rely mainly on shallow-wells, rivers, streams and ponds for their daily water needs (Nevondo and Cloete, 1991). In most cases water from these sources is used directly without treatment and the water sources may be faecally contaminated (WHO, 1993). Simple low-cost on-site sanitation methods have been developed to dispose faecal matter, mainly because of their economic advantage. However, the biggest drawback is the well-recognized potential to pollute groundwater resources (ARGOSS, 2001; Lewis et al., 1980), which conflicts with Integrated Water Resources Management principles, some of which are to maintain water quality and quantity and vital ecosystems. Given the widespread use of shallow groundwater for domestic purposes in rural areas, maintaining groundwater quality is a critical livelihood intervention. Globally, the larger part of the population lives in rural areas and in Africa it is estimated that these people represent approximately 70 to 80% of the continent’s population. In Zimbabwe about 70% of the population live in the rural areas and approximately the same percentage rely on groundwater (Chenje et al., 1998). That reliance may be higher in some districts of Zimbabwe as noted by Hoko (2004), where rural communities like Gokwe, Nkayi, Mwenezi and Lupane, mainly use groundwater for domestic purposes with very little reliance on surface water. Yet there is an information gap on the levels of groundwater contamination from pit latrines in Zimbabwe (Chenje et al., 1998; Chidavaenzi et al., 1999). Therefore the quality of groundwater, 3 which potentially can be affected by on-site sanitation systems, must be carefully assessed in order to reduce the health and environmental risk. This study was carried out in Kamangira Village, Marondera district, Zimbabwe. As is the case with most rural communities in the country, the people of Kamangira Village mainly use shallow-wells as a source of domestic water and other purposes and pit latrines for sanitation. The geological set-up and soil type in the area, compounded by a generally high water table, are thought to have caused several pit latrine failures such as cracking, sinking and over flooding. According to Lewis et al. (1980), failure of on-site sanitation systems may result in serious pollution of groundwater, the primary cause for health concerns being the excreted pathogens and certain chemical constituents like nitrate. The study assessed impacts of pit latrines on groundwater quality, taking levels of total and faecal coliforms, ammonia (NH3-N), nitrite (NO2--N) and nitrate (NO3--N), conductivity, turbidity and pH as impact indicators. The parameters chosen are those that a wide range of studies, internationally have demonstrated to be problematic with regards to on-site sanitation. Some of the parameters also tend to have an effect on the perceived water quality and also on health. A disease incidence survey was carried out in order to assess the possible health impacts of groundwater pollution. The overall aims of the study were to contribute towards the improvement of safe water supply and sanitation services and to recommend alternative mitigatory and management measures where necessary. 2. STUDY AREA Kamangira Village is in Chihota rural area, Marondera District, in Zimbabwe and the District’s geographical location is shown in Figure 1. The village has a population of about 100 people and the homesteads follow a linear settlement pattern. The pick rainy period for the area is 4 December to February, while June to September are the dry months, with very isolated rainy days in June and August. Key: Study site N Marondera Figure 1 Map of Zimbabwe and Marondera district. (Adapted from: www.zimrelief.info/files/attachments/2002%20population%20summary.jpg) The predominant form of sanitation is pit latrines whose impacts on groundwater quality was the main objective of the study. The main source of domestic water is shallow-wells. Chihota rural area is truncated by numerous faults, of which two major sets are outstanding, the north/northeast and north-east trending sets. These faults tend to have a major influence in controlling the drainage of the area (Mukandi, 2005), with intrusive features like dykes enhancing the groundwater potential of rocks, thereby increasing the transmission properties of the aquifer (Maziti, 2002). At a localized scale, Kamangira Village is covered with granitic rocks and the soils are pale-sandy. 3. MATERIALS AND METHODS. 3.1 Study site design. Figure 2 presents the study site design. The study site was situated on a watershed, which meant 5 that the actual setup could be designed so as to exclude groundwater flow from some parts of the drainage system. Pit latrines under investigation were marked PL1, PL2 and PL3, and the shallow-wells close to those latrines were marked SW1, SW2, and SW3 respectively. Shallowwell (SW1) was located 44 m southeast of pit latrine (PL1), shallow-well (SW2) at 38 m north of pit latrine (PL2), and shallow-well (SW3) was located 44 m south of pit latrine (PL3). SW2 TW10 SW2 7990560 TW9 TW8 TW7 PL2 TW6 7990540 7990520 TW13 PL2 CONTROL TW5 PL3 TW12 7990500 PL3 TW11 TW4 PL1 TW3 SW1 SW3 7990480 TW2 PL1 TW1 7990460SW3 SW1 300660 300680 300700 300720 300740 300760 300780 300800 300820 300840 Figure 2 Study site design. The positions of pit latrines within the study site itself provided an ideal set-up where two pit latrines could be joined along a transect and their impacts on groundwater quality investigated, either individually or combined. A total of 14 monitoring boreholes were drilled upstream and downstream of pit latrines, at positions marked in Figure 2, using a Vonder Rig. The boreholes were cased using perforated 125 mm PVC pipe. Figure 2 also shows the location of the control borehole at 80 m north-east of PL1 and 100 m east of PL2. The control borehole was also cased in the same manner as the other boreholes. 3.2 Sampling and analysis methods Six sampling campaigns were made between February 2005 and May 2005, covering the rainy season. Boreholes were flushed once before commencement of the sampling campaign. 6 Subsequent flushing at every sampling event could not be done because some of the parameters which were to be tested for were sensitive to water disturbances. Furthermore, the perforation of the casing was assumed to allow through-flow of groundwater. Groundwater samples were collected at the water surface from the boreholes and the shallow-wells. Brickwork and heavy concrete slabs protected the boreholes and the casings were opened only for sampling purposes. The samples were analysed for NH3-N, NO2--N, NO3--N, conductivity, turbidity and pH, according to standard methods as prescribed in the Water and Wastewater Examination standard methods handbook of 1989 (APHA, 1989). Water quality data was analysed using Microsoft Excell and Surfer 7 software packages and compared to WHO Guidelines for drinking water (WHO, 2004). 3.2.1 Water and soil tests For coliforms, microbiological tests were performed on duplicate 50 ml samples, after filtering the sample portions through individual 0.45 μm membrane filter papers, as stipulated in the Membrane Filter Technique for members of the coliform group (method number 9222). NH3-N was determined as described in method number 4500-NH3 F. NO2--N was determined as described in the Palintest Nitricol Field Kit method. NO3--N was determined according to the Ultraviolet Spectrophotometric Screening Method number 4500-NO3- B. Conductivity was determined by emersing the probe of a WTW Cond 340i test kit into the water samples. The results were read off the instrument directly. Turbidity was read off the HACH 2100N Turbidimeter against distilled water set at zero. A microprocessor pH/ion meter pMX 3000 measured pH. The sieve test was performed on soil samples collected at varying depths along the monitoring boreholes for soil particle size determination. The analysis was performed using a series of B.S. sieves nested as follows: 19 mm, 9.5 mm, 4.75 mm, 236 mm, 1.18 mm, 600 μm, 300 μm, 150 μm and 75 μm. Permeability was calculated from the obtained sieve analysis data. 7 3.2.2 Disease incidence Incidences of water-borne diseases in the study area were investigated by conducting a survey in Kamangira Village. Direct interviews were held using semi-structured questionnaires. A total of 38 homesteads were interviewed, including the three homesteads that comprised the study site. Information gathered included sources of water for domestic purposes, protection of the water source, relative distances between sanitary structures and domestic water sources, awareness of potential water contamination from pit latrines, and the most common water related diseases that affected the villagers. Results from the survey were used to make preliminary inferences of health impacts of groundwater pollution and contamination by pit latrines. 4. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION 4.1 Groundwater flow and water table From Figure 2, transect 1 comprised PL1, PL2 and the boreholes TW1 to TW10, while transect 2 comprised PL3 and TW11 to TW13. Groundwater was assumed to flow along the transects as follows: For transect 1 the flow was from TW1 towards TW4, from TW7 towards TW4 and from TW7 towards TW10. In terms of groundwater flow, monitoring boreholes TW1 and TW7 were upstream in relation to pit latrine positions while TW2 and TW6 were downstream boreholes. For transect 2, flow was assumed to be from TW11 towards TW13, with TW11 being upstream and TW12 and TW13 being the downstream boreholes of pit latrine (PL3). The contour map in Figure 2 indicated that there was a marked depression around TW4. Figure 3 highlights the relationships between pit base elevations and water tables along transect 1. It also shows the drop in water table in boreholes along the transect and highlights the depression around TW4. Considering boreholes close to PL1, the pit latrine generally lay above the water tables of TW1 and TW2 throughout the sampling period. It ranged 0.2 to 1.2 m above water tables for TW1 and 0.6 to 1.8 m above those for TW2. These ranges gave an average soil infiltration layer range of 0.4 to 1.5 m above the water table. PL2 sat on and below the water 8 table throughout the study. It ranged 0.9 m below the water table to 0.2 m above the water table of TW6. It also ranged 1.7 to 0.6 m below the water table of TW7. Along transect 2, according to Figure 4, PL3 pit base sat below the water table throughout the study, ranging 3.2 to 1.2 m and Ground level just after drilling 21-Feb 1427.5 1427.0 1426.5 1426.0 1425.5 1425.0 1424.5 1424.0 1423.5 1423.0 1422.5 1422.0 7-Mar 21-Mar tw10 tw9 tw8 tw7 tw6 tw5 tw4 tw3 tw2 4-Apr tw1 elevation (m) 3.1 to 1.2 m below the water tables of TW11 and TW12 respectively. w ater table elevation variation against pit base elevation 18-Apr 5-May PL1 PL2 Figure 3 Water table elevations for boreholes on transect 1. The fact that there was little or no soil infiltration layer between the pit latrine base and the water table meant that effluent could seep into the water table and contaminate groundwater. The soil Ground level just after drilling 21-Feb 1426 1425 1424 1423 1422 1421 1420 1419 7-Mar tw13 tw12 21-Mar tw11 elevation (m) infiltration layer is that soil layer between the pit base and the water table. 4-Apr 18-Apr w ater table elevation variation against pit base elevation 5-May PL3 Figure 4 Water table elevations for boreholes on transect 2. 9 PL3 could actually be considered as injecting raw pit latrine effluent into the surrounding groundwater as highlighted in figure 4. Much of the results in terms of water quality tended to depend on the depth of the soil infiltration layer allowed between the pit base and the water table, as stated in a review of typical case studies by Lewis et al., (1980). 4.2 Soil characterization Soil characterization was done and results showed that the soils were generally sandy and collapsible. Soil permeability results ranged 0.02-2.7 md-1, within the range of 0.01-2.8 md-1 as noted by (Wright, 1992) for a crystalline basement. Permeability values for soils around PL1 and PL2 were found to be lower than those for soils around PL3. This may have helped in some of the transport mechanisms. An example was the extent and persistence of ammonia in TW12, but whose pattern was not very distinct in TW2 and TW6, all of which were downstream boreholes. 4.3 Coliforms Total and faecal coliforms both ranged 0-TNTC (too-numerous-to-count), with 78 % of the total results meeting 0 CFU/100ml WHO guidelines value. The shallow-wells were located 38-44 m away from the nearest pit latrines, thereby placing them outside the pit latrines’ radii of influence of 30 m as generally accepted in Zimbabwe. All of them were partially protected and they indicated elevated levels of both total and faecal coliforms. This could be due to water withdrawal practices around the water point, which could have caused introduction of coliforms by the users of the water points. Shallow-wells SW1 and SW3 served more people (5 and 7, respectively) than SW2 (3 people), resulting in a higher demand on the former two shallowwells, with consequential soil re-suspension and a higher potential for microbiological contamination. Variations of coliforms counts are indicated graphically in Figures 5 and 6. 10 CFU/100mL 2016.0 PL1 PL2 PL3 1516.0 1016.0 516.0 sw3 sw2 sw1 control tw13 tw12 tw11 tw10 tw9 tw8 tw7 tw6 tw5 tw4 tw3 tw2 tw1 16.0 Sam ple point 21-Feb 7-Mar 21-Mar 4-Apr 18-Apr 5-May Figure 5 Total coliform variation. WHO guidelines value of 0 CFU/100 ml was not met in 100% of total and faecal coliform results obtained for shallow-wells. The results obtained for some boreholes located within a 5 m radius of the pit latrines indicate that a pit latrine can influence up to 5 m of its radius. Beyond 5 m the faecal coliforms are greatly reduced. The fact that TW6 had no coliforms but they were detected in TW7 could indicate that predominantly groundwater flow was towards TW10 rather than towards TW4. The results for TW11 and TW1, both being upstream of pit latrines, confirmed that flow from pit latrines PL1 and PL3 was from a higher to a lower gradient. Borehole TW10 did not show indications of impacts from the old and collapsed pit latrine that 1000 800 600 400 sw3 sw2 sw1 control tw13 tw12 tw11 tw10 tw9 tw8 tw7 tw6 tw5 tw4 tw3 tw2 200 0 tw1 CFU/100mL had collapsed into the ground some 5 m away from that borehole in terms of coliforms. Sam ple point 21-Feb 7-Mar 21-Mar 4-Apr 18-Apr 5-May Figure 6 Faecal coliform variation. 11 The presence of faecal coliform bacteria in most samples indicated that the water had been contaminated with the faecal material of man or other animals and therefore there was a risk of contamination by pathogens or disease producing bacteria or viruses, which could also exist in faecal material. The presence of faecal contamination was an indicator that a potential health risk existed for individuals exposed to that water. 4.3 Ammonia–nitrogen Ammonia–nitrogen ranged 0-2.0 mg/l for all sampling points, with 99 % of total results falling within 1.5 mg/l WHO recommended value. The threshold odour concentration of ammonia at alkaline pH is approximately 1.5 mg/l, and a taste threshold of 35 mg/l has been proposed for the ammonium cation (NH4+). Ammonia-nitrogen persisted in samples from TW12 as indicated in Figure 7. NH3-N (mgN/L 2.50 2.00 1.50 1.00 0.50 sw3 sw2 sw1 control tw13 tw12 tw11 tw10 tw9 tw8 tw7 tw6 tw5 tw4 tw3 tw2 tw1 0.00 sam ple point 21-Feb 7-Mar 21-Mar 4-Apr 18-Apr 5-May Figure 7 Ammonia–nitrogen variation. This could have been because that monitoring borehole was located downstream of PL3, the pit latrine that sat inside the water table throughout the study period. Diffusion processes could have enhanced ammonia movement in water and soil matrix. Ammonia usually occurs in drinking water at concentrations well below those at which toxic effects may occur. The pit latrine with its base inside the water provided a continuous source of ammonia, unlike the other boreholes that were 5 m downstream of pit latrines whose bases did not continuously interact 12 with the water table. The collapsed and disused pit latrine could have impacted TW10. Ammonia is not of direct relevance to health at levels generally detected in groundwater, and no health-based guideline value has been proposed. 4.4 Nitrite-nitrogen Overall results show that nitrite–nitrogen ranged 0.0-0.64 mg/l and this was within the 3 mg/l WHO guidelines value. The Zimbabwean standard value of 0.001 mg/L was surpassed though, for 26 % of the results. High levels of nitrite-nitrogen were detected at TW4 (Figure 8), which is at the depression on transect 1, as noted in Figure 2. The borehole is also located furthest 0.70 0.60 0.50 0.40 21-Feb 7-Mar 21-Mar 4-Apr 18-Apr sw3 sw2 sw1 control Sam ple point tw13 tw12 tw11 tw10 tw9 tw8 tw7 tw6 tw5 tw4 tw3 tw2 0.30 0.20 0.10 0.00 tw1 NO2-N (mgN/L) downstream for both PL1 and PL2. 5-May Figure 8 Nitrite–nitrogen variation. The conversion from ammonia to nitrite with time and also with exposure to air is also noted in TW4 where the first sampling campaign recorded lower levels of nitrite-nitrogen. The rise in concentration in the second sampling campaign also coincided with the non-detection of ammonia-nitrogen in that same sample at that particular sampling point. TW10 shows the impact of old t located 5 m away from it, although it is 45 m downstream of PL2. On transect 2, TW12 is downstream of PL3, whose base sat inside the water table continuously. Results of nitrite confirm that this species is found usually in low levels and is usually not stable. 13 Regarding health, nitrite ion can oxidize iron in the haemoglobin molecule, from the ferrous to the ferric ion. The resultant methaemoglobin is incapable of reversibly binging oxygen, and consequently anoxia or death may ensue if the condition is left untreated. 4.5 Nitrate-nitrogen Nitrate-nitrogen for all sampling points ranged 0.0-6.7 mg/l and this was within the 10 mg/l WHO guidelines value. The tendency for nitrate-nitrogen to concentrate around the depression NO3- -N (mg/L) at TW4 was noted in Figure 9. 8.0 6.0 4.0 2.0 sw3 sw2 sw1 control tw13 tw12 tw11 tw10 tw9 tw8 tw7 tw6 tw5 tw4 tw3 tw2 tw1 0.0 sam ple point 21-Feb 7-Mar 21-Mar 4-Apr 18-Apr 5-May Figure 9 Nitrate-nitrogen variation. TW7 showed that it was being impacted by PL2, but that nitrate movement towards TW10 was quite slow due to the very small gradient fromTW7 to TW10. The gradient from TW6 to TW4 was much steeper and this promoted the concentration of nitrate-nitrogen at TW4. The collapsed and disused pit latrine did not show its impacts on TW10. High levels of nitrate-nitrogen are directly associated with methaemoglobinaemia, or "blue baby syndrome", an acute condition which is most frequently found among bottle-fed infants of less than 3 months of age. Nitrates and nitrites have been suggested as possible carcinogens by a number of researchers. Researchers have also confirmed that nitrate can be used as a crude indicator of faecal pollution where microbiological data are unavailable. 14 4.6 Conductivity Conductivity ranged 46-370S/cm. There are no WHO guideline values for conductivity. On transect 1 involving TW1 up to TW10, conductivity rose from TW1 towards and picked at a location 25 m away, at TW4, before it dropped gradually towards PL2. It also rose gradually from TW7 towards TW10, which was located 45 m away from TW7. Transect 2 involving TW11 to TW13, showed that conductivity was lower at TW11, which was located 5 m upstream of PL3 than at TW12, which was located 5 m downstream of that pit latrine. The significant levels of ammonia at TW12 could possibly affect the conductivity. Conductivity dropped significantly at a distance 15 m downstream of PL3 to values almost similar to those for the control borehole. The concentration of ions at TW4, TW10 and TW12 could be due to impacts of PL1, PL2 and PL3 as well as the collapsed pit latrine 5 m away from TW10. The low values for the shallow-wells indicated that there were very insignificant contributions of ions from the vicinity of the shallow-wells 4.7 Turbidity Turbidity ranged 1-45 NTU, 59 % of results meeting the 5 NTU WHO guidelines limit. Turbidity showed a decreasing trend from TW1 to TW7 and rose again along transect 1, with a pick at TW10. The high turbidity at TW10 could be as a result of loose soil from the collapse of the disused pit latrine near that borehole. Since the earth acts as a filter, turbidity decrease towards the depression at TW4 was expected. Transect 2 turbidity values were generally much higher than those for transect 1. High turbidity values were also recorded for the shallow-wells SW1 and SW3 and this could be due to the disturbance of the soil within the well during water withdrawal. The depth of the shallow-wells, and in particular, the depth of the water level above the well bottom is crucial. In this study, the deepest well was SW3 and the shallowest was SW2. The water levels also showed the same trend for all sampling dates. The turbidity values though were highest at SW1 and lowest at SW2, and this could be due to the fact that the base of SW2 15 was covered by a large boulder, making the soil intact, whereas the soil in SW1 and SW3 was loose. The control borehole recorded very low values for turbidity. Solid particles suspended in water absorb or reflect light and cause the water to appear cloudy. Turbidity affects water aesthetics. 4.8 pH The pH ranged 6.8 to 7.9 for both shallow-wells and boreholes. Values recorded for boreholes along transect 1 were relatively close to those for the control, although they picked at TW10. Transect 2 pH values rose from TW11 located 5 m upstream of the pit latrine, PL3, and picked at TW12 that is 5 m downstream, before dropping noticeably at TW13 located 15 m downstream of PL3. The presence of ammonia-nitrogen at TW12 could have caused the elevated pH levels at borehole TW12. Ammonia-nitrogen presence makes the environment alkaline, thereby raising pH. Shallow-wells recorded much lower pH values. 4.9 Survey Thirty-eight villagers were interviewed, representing 38% of the population of Kamangira Village. Of the respondents who owned a pit latrine, 45% of them were unusable because they were dilapidated and unsafe (according to sentiments passed by the respondents during the interviews) or they were now too full to be used hygienically. Those who did not have a water point within the homestead represented 42 % of the respondents. This percentage is quite typical of rural communities in the third world countries where half the population remain unserved with basic water and sanitation facilities. Diarrhoea was widespread, with those having suffered from it making up 50 % of the interviewed number. Those who did not own a water point and also suffered from diarrhoea constituted 24 % of the respondents. There was no incidence of health impacts from nitrate, as depicted by 0 % occurrence of “blue-baby” syndrome, whose symptoms had been explained by the interviewer. Preference of sanitation technology revealed that 37 % 16 of the respondents would like to own eco-san which is a form of on-site sanitation, although 100 % of them sited unavailability of financial resources as the major drawback. Seven standard cement bags were required to build the structure, besides the labour and brick requirements according to a local Non-Governmental Organisation, which was implementing eco-san. 5. CONCLUSIONS Total and faecal coliforms were found to be impacting negatively on groundwater quality. Samples that gave the 0 CFU/100 ml limit represented 78 % of the total results. Samples from pit latrines that gave positive results for coliforms counts represented 14% of total results. Ideally, 100 % of the results should meet that figure for that water to be declared safe for human consumption. Ammonia-nitrogen, nitrite-nitrogen and nitrate were found to be impacting on the groundwater quality. However their levels were not yet of health concern according to the WHO guideline values and recommendations. Turbidity of the water was above limit for 41 % of the results, making it aesthetically unpleasant for domestic purposes. Although there are no WHO guideline values for conductivity and pH, the results obtained in this study were found not to be of health concern according to the Zimbabwean domestic water standards. The sandy nature of the soils in the study site, compounded by the high water table, was found to be unsuitable for pit latrine construction, resulting in several structural failures. Generally, it may be unsafe to abstract water within 25 m distance from a pit latrine. Although eco-san was the most preferred sanitation alternative during the survey, 100 % of the respondents sited unavailability of funds to construct the urine separation and composting structures. 17 6. RECOMMENDATIONS It would be logical to treat each settlement or site on individual merit when assessing the faecal pollution risk associated with on-site sanitation. However the economics and logistics of lowcost sanitation schemes are such as to preclude the routine use of costly hydrogeological field investigations. Therefore the following recommendations are suggested when assessing the risk of on-site sanitation before implementation. The depth of the infiltration layer as well as the direction of groundwater flow were found to be critical parameters during the assessment of the impacts of pit latrines on groundwater and could be investigated easily before implementation of on-site sanitation. History regarding location of collapsed pit latrines could be very important since disregarding this factor could end up having a homestead taping domestic water close to or from a disused pit latrine. Raised pit latrines and other low-cost technologies could be considered as alternatives because they minimize the risk of releasing flow across the thin infiltration layer. The results obtained from the study are true for the study area but could also apply to areas with similar soil, geology and rainfall pattern. An integrated approach involving geotechnology, hydrogeology and groundwater pollution could be considered as a way forward in efforts to solve the sanitation problems in view of structural failures within the larger Kamangira Village. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The authors would like to sincerely thank Mvuramanzi Trust and The WaterNet Regional Capacity Building program, for funding this research. Special thanks go to the Department of Civil Engineering and Department of Geology at the University of Zimbabwe, for their logistical, material and moral support. 18 LITERATURE CITED Anon, J. (1996). World Water Environmental Engineering. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom. APHA, (1989). Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater, 17th edition. APHA, Washington, DC, United States of America. ARGOSS, (2001). Guidelines for assessing the risk to groundwater from on-site sanitation. British Geological Survey Commissioned Report, CR/01/142. 97pp. United Kingdom. Chenje, M., Sola, L., and Paleczny, D. (editors). (1998). The State of Zimbabwe’s Environment 1998. Government of the Republic of Zimbabwe, Ministry of Mines, Environment and Tourism, Harare, Zimbabwe. Chidavaenzi, M., Bradley, M., Jere, M., and Nhandara, C. (1999). Pit Latrine effluent infiltration into groundwater: The Epworth case study, Water Science and Technology Journal,1999. Hoko, Z. (2004). An assessment of water quality of drinking water in rural districts in Zimbabwe. The case of Gokwe South, Nkayi, Lupane and Mwenezi Districts. Paper presented at the 5th Waternet/Warfsa Symposium “Water and Health”. Windhoek, 1-5 November 2004. Namibia. Lewis, J.W., Foster, S.D., and Draser B.S. (1980). The risk of groundwater pollution by on-site sanitation in developing countries, a literature review. Maziti, A. (2002). Groundwater occurrence and development potential for lineament orientations of crystalline rock aquifers of Gutu-Buhera area. M.Sc.Thesis, University of Zimbabwe, Harare, Zimbabwe. Mukandi, M.A. (2005). The geology of a portion of Seke-Chihota Communal Lands (Based on Landsat and SPOT Image Interpretation). Zimbabwe Geological Survey, Zimbabwe. Nevondo, T.S. and Cloete, T.E. (1999). Bacterial and chemical quality of water supply in the Dertig village settlement. Water SA 25: (2) 215-220. 19 Nsubuga, F.B., Kansiime, F., and Okot-Okumu, J. (2004). Pollution of protected springs in relation to high and low density settlements in Kampala – Uganda. Physics and Chemistry of the Earth 29: 1153-1159. Standards Association of Zimbabwe (SAZ), (1997). Zimbabwe standards specification for water for domestic supplies. Zimbabwe Standard No. 560:1997. ICS 13.060.20. ISBN 0-86928-469-X, Zimbabwe. WHO, (1993). Guidelines for Drinking Water Quality. Vol.1 Recommendations, second edition. World Health Organisation, Geneva, Switzerland. WHO, (1996). Guidelines for Drinking Water Quality. Vol.2: Health and Supporting Criteria, second edition. World Health Organisation, Geneva, Switzerland. WHO, (2004). Guidelines for Drinking-Water Quality. Vol.1: Third Edition. World Health Organisation, Geneva, Switzerland. Http://www.zimrelief.info/files/attachments/2002%20population%20summary.jpg. 21/3/05. 20