MOTM STREPTOMYCIN

advertisement

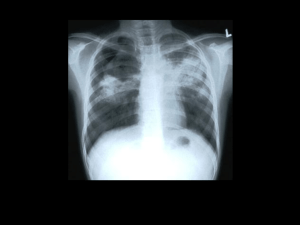

STREPTOMYCIN And other drugs to treat Tuberculosis Surely Tuberculosis is a disease of the past? You're thinking of Fantine, the character played by Anne Hathaway in the latest version of Victor Hugh's Les Miserables. Sadly, TB is very much with us; around 1/3 of the world's population is probably infected with it and it actually kills nearly 2 million people a year. Most of these victims are in the developing world, so you don’t hear much about them. There is a list as long as your arm of famous people killed by TB – several of the Bronte sisters as well as other writers including Elizabeth Barrett Browning, Anton Chekhov, Franz Kafka, John Keats and George Orwell; the composers Frédéric Chopin, Luigi Boccherini and Giovanni Battista Pergolesi; the actress Vivien Leigh, heroine of Gone With The Wind; Simon Bolivar the liberator of Colombia, Venezuela, Ecuador, Peru and Bolivia; Saint Theresa of Lisieux; and King Edward VI of England. Following the Industrial Revolution, TB was a major cause of death in overcrowded and insanitary cities, whilst a regular cause of death of a (fictional) heroine in opera, just think of La Traviata, La bohème, The Lady of the Camellias and The Tales of Hoffmann. What causes it? The scientist Robert Koch discovered the tubercule bacillus in 1882, winning the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for this in 1905. TB is caused by a bacterium, most usually Mycobacterium tuberculosis, a search for a cure went on for many years. In the early 20th century, sanatoria to treat tuberculosis were a great step forward, but the first drug effective against TB was not discovered until the 1940s. And it can be treated? Streptomycin was the first molecule active against TB; it was isolated by Albert Schatz and Selman Waksman at Rutgers University in the United States. Waksman’s family emigrated from the Ukraine to American when he was young. He had originally been a student at Rutgers, moved to California to carry out the research that led to his PhD, and later returned to Rutgers. He had a lifelong interest in microorganisms in the soil, and the 1930s saw the discovery of the sulfa drugs, the first antibiotic (MOTM July 2011), followed by penicillin. In 1939 Waksman started a research programme studying study soil microorganisms that might have antibiotic properties against pathenogenic bacteria. Albert Schatz began working in Waksman’s laboratories in 1942; after a brief spell in the US Army, where he began to look for antibiotics that could be active against penicillin-resistant bacteria, from which he was discharged on health grounds, he returned to Waksman, worked in a basement lab that could easily be isolated from the rest of Waksman’s laboratories in the event of the bacterium escaping. Schatz chose to work with a very virulent form of Mycobacterium tuberculosis, supplied by William Feldman. Together with Corwin Hinshaw, Feldman worked at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, looking for antibiotics active against TB. Schatz discovered two strains of a bacterium that made an antibiotic he called streptomycin, which was active against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Streptomycin is in fact active against many pathogens. After Schatz and Waksman reported the activity of streptomycin against tuberculosis in test organisms in 1944, Feldman and Hinshaw showed that streptomycin would successfully treat TB in humans. Schatz was to receive his PhD in 1945. Both Schatz and Waksman were named on the application to patent streptomycin, awarded in 1948. Waksman persuaded Schatz to sign over his rights to receive royalties to Rutgers; subsequently he found out that Waksman had an agreement with Rutgers to receive 20% of royalties, and also learned that Waksman was playing down Schatz’s role in the discovery. Schatz successfully sued the Rutgers Foundation, as well as Waksman, for a share of the royalties and recognition of his role in the discovery of streptomycin. An out-of-court settlement in 1950 awarded Schatz $120,000 for the foreign patent rights, and 3% of the royalties, representing about $15,000 per annum for several years. However, when the 1952 the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine was awarded to Waksman "for his discovery of streptomycin, the first antibiotic effective against tuberculosis", there was no mention of Schatz, nor of Feldman and Hinshaw, who had shown that streptomycin was effective in human sufferers from tuberculosis. How does Streptomycin work? It is an antibiotic which acts against a wide range of both Gram positive and Gram negative bacteria (in contrast to penicillin, which only acts against Gram-positive bacteria); it inhibits protein synthesis in the bacterium, binding to the rRNA in the ribosome, distorting the ribosomal decoding site and inhibiting binding of tRNA. So what's the problem? For one thing, bacteria become resistant to streptomycin. Fortunately, other molecules have been found to be active against TB. One of them is the simple molecule PAS, para amino salicylic acid. Because PAS has a similar structure to 4aminobenzoic acid, which bacteria use to make folic acid, PAS was long believed to interfere with this process by a similar means of action to the sulfa drugs, but now it is thought that it acts on the folate pathway by generating molecules that are poisonous to the bacterium. Another of these is isonicotinic acid hydrazide (isoniazid); this inhibits cell wall synthesis. It is a prodrug, and one active molecule it produces is NO, as does the more recently discovered PA-824, which is still in the experimental stage. There is also rifampicin, an antibiotic which blocks RNA synthesis. Nevertheless, multi-drug-resistant TB is an increasing problem. The cause is partly due to patients not completing courses of antibiotics; even though they are partly cured, they still carry the bacterium. The bacterium is more easily spread due to greater population mobility, as well as air travel. Many AIDS sufferers have severely weakened immune systems and develop TB, which is responsible for ¼ of HIV deaths. Multi-drug-resistant TB is a real problem. Is there any hope of a treatment for that? A molecule called Bedaquiline has just been approved for cases of this, though it does have some possible side-effects in patients with cardiac arrythmias. Bedaquiline works by targeting the proton pump for ATP synthase in the bacterium, a different target to other anti-TB drugs. Another experimental drug called Delamanid acts by inhibiting mycolic acid synthesis, and trials indicate improved outcomes in patients with multidrug-resistant TB. One source of encouragement is that many drugs are now known that target the bacterium in different ways, so that use of a cocktail of many of these offers real hope. But TB still can be a sentence of death? It can be, but many have recovered from it, and their stories are often inspiring. Take the Yorkshire cricketer Bob Appleyard. He took 200 first class wickets in the 1951 season, whilst unknowingly suffering from TB. In 1952 he was successfully treated with streptomycin, then had surgery to remove the infected part of the lung, and convalesced in 1953, so he missed two whole seasons’ play. He recovered his health, and regained his form, despite reduced lung capacity, not just getting back into the Yorkshire XI but being selected for England, helping them retain the Ashes in their tour of Australia in 1954-5. Bibliography Books about TB and antibiotics M. Wainwright, Miracle Cure: Story of Antibiotics, Wiley-Blackwell, 1990. F. Ryan, Tuberculosis: The Greatest Story Never Told - The Search for the Cure and the New Global Threat, Swift Publishers, 1992. T. Dormandy, The White Death: A History of Tuberculosis, Hambledon Continuum, 1998. J. Mann, The Elusive Magic Bullet, Oxford, OUP, 1999. H. Bynum, Spitting Blood: The history of tuberculosis, Oxford, OUP, 2012. P. Pringle, Experiment Eleven: Deceit and Betrayal in the Discovery of the Cure for Tuberculosis, London, Bloomsbury, 2012 (Schatz’s notebooks) Discovery of Streptomycin and its role A. Schatz, E. Bugie and S. A. Waksman, Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med., 1944, 55: 66-69; D. Jones, H. J. Metzger, A. Schatz and S. A. Waksman, Science, 1944, 100, 103-105. (discovery of properties) W. H. Feldman and H. C. Hinshaw, Proc. Staff Meet., Mayo Clinic., 1944, 19, 593-599. (effect on guinea pigs) H. C. Hinshaw and W. H. Feldman, Proc. Staff Meet., Mayo Clinic., 1945, 20, 313-318; H. C. Hinshaw, W. H. Feldman and K. H. Pfeutze, J. Am. Med. Assoc., 1946, 132, 778782; W. McDermott, C. Muschenheim, S. J. Hadley, P. A. Bunn and R. V. Gorman, Ann Intern Med. 1947, 27, 769-822 (streptomycin and TB in humans) J. H. Comroe, American Review of Respiratory Disease, 1978, 117, 773–781 and 957968. (story of streptomycin) A. Schatz, Actinomycetes, 1993, 4, 27-39. (his account of the development of streptomycin) Streptomycin and how it works F. A. Kuehl, R. L. Peck, C. E. Hoffhine and K. Folkers, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1948, 70, 2325-2330 (structure of streptomycin). H. Demirci, F. Murphy, E. Murphy, S. T. Gregory, A. E. Dahlberg and G. Jogl, Nature Communications, 2013, 4, 1355 (how streptomycin works) Other treatments for TB D. D. Martin, F. S. Spring, T. G. Dempsey, C. L. Goodacre and D EW Seymour, Nature, 1948, 161, 435 (p-Aminosalicylic acid in the treatment of tuberculosis). C. K. Stover, P. Warrener, D. R. VanDevanter, D. R. Sherman, T. M. Arain, M.H. Langhorne, S. W. Anderson, J. A. Towell, Y. Yuan, D. N. McMurray, B. N. Kreiswirth, C. E. Barryk and W. R. Baker, Nature, 2000, 405, 962-966 (PA 824). K. Andries et al., Science, 2005, 307, 223-227 (discovery of bedaquiline) M. Protopopova, E. Bogatcheva, B. Nikonenko, S. Hundert, L. Einck and C. A. Nacy, Med. Chem., 2007, 3, 301–316. (TB cures, reviews) A. M. Ginsberg, M.W. Laurenzi, D. J. Rouse, K. D. Whitney and M. K. Spigelman, Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., 2009, 53, 3720-3725 (PA 824) Q. Huang, J. Mao, B. Wan, Y. Wang, R. Brun, S. G. Franzblau and A. P. Kozikowski, J. Med. Chem. 2009, 52, 6757–6767 (2-Methylbenzothiazoles as treatments for TB) G. A. Marriner, A. Nayyar, E. Uh, S. Y. Wong, T. Mukherjee, L. E. Via, M. Carroll, R. L. Edwards, T. D. Gruber, I. Choi, J. Lee, K. Arora, K. D. England, H. I. M. Boshoff and C. E. Barry, Top. Med. Chem., 2011, 7, 47–124 (major review of chemotherapies for TB) M. T. Gler et al, N. Engl. J. Med., 2012, 366, 2151-2160 (Delamanid) J. Avorn, JAMA, 2013, 309, 1349- 1350 (FDA approval for bedaquiline) A. Maxmen, Nature, 2013, 502, S4 – S6 (combinational therapy for TB) V. Skripconoka et al., Eur. Respir. J., 2013, 41, 1393–1400 (Delamanid) Other works cited R. B. Mason, Can. Med. Ass. J., 1996, 154, 921-922 (TB and opera) S. Chalke and D Hodgson, No Coward Soul, Bath, Fairfield Books, 2003. (Bob Appleyard) T. Paulson, Nature, 2013, 502, S2-S3 (worldwide distribution of TB) Picture ideas (most well-known people have far more than one) Anne Hathaway as Fantine http://media.theiapolis.com/d8-iN04-k9-lP13/anne-hathaway-as-fantine-in-lesmiserables.html (and many others) George Orwell http://img.dailymail.co.uk/i/pix/2007/09_01/orwellDM0509_468x417.jpg Simon Bolivar http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/2/2f/Sim%C3%B3n_Bol%C3%ADv ar_2.jpg Keats http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/1/1a/John_Keats_by_William_Hilt on.jpg Chopin http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/3/33/Chopin,_by_Wodzinska.JPG Vivien Leigh http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/0/0a/Vivien_Leigh_Gone_Wind_R estaured.jpg Robert Koch http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/9/99/Robert_Koch_BeW.jpg Albert Schatz http://static.guim.co.uk/sysimages/Admin/BkFill/Default_image_group/2012/6/26/1340720405968/AlbertSchatz-008.jpg or http://blogs.haverford.edu/haverblog/files/2012/05/schatz001.jpg Selman Waksman http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/3/33/Selman_Waksman_NYWTS.j pg Bob Appleyard http://p.imgci.com/db/PICTURES/CMS/56800/56831.jpg http://p.imgci.com/db/PICTURES/CMS/56800/56833.1.jpg