Web Colerdige KK

advertisement

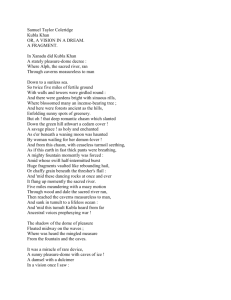

http://poetry.about.com/od/poems/a/kublakhanguide_3.htm Dreaming of Xanadu: A Guide to Samuel Taylor Coleridge's poem "Kubla Khan" Notes on Content By Bob Holman & Margery Snyder, About.com See More About: samuel taylor coleridge british romantic poetry kubla khan xanadu Sponsored Links Free A+ Study Guide (PDF)Essential Facts You Must Know. Instant Download, Get It Now!www.PrepLogic.com HSC - Get Ahead for 2009Free Study/Exam Skills Lecture Free Exams, Notes, Essays & Tipswww.tsfx.com.au A Wedding Wishing WellMakes It Easy For Friends & Family To Give Exactly What You Needwww.OurWishingWell.com Poetry Ads Narrative Poems Sorry Boyfriend Poems Funny Valentine Poems Short Poems Humorous Poems (Continued from Page 2) The Poem Notes on Context Notes on Form Notes on Content Commentary and Quotations “Kubla Khan” is a poem clearly meant to be spoken. So many early readers and critics found it literally incomprehensible that it became a commonly accepted idea that this poem is “composed of sound rather than sense.” Its sound is beautiful -- as will be evident to anyone who reads it aloud. The poem is certainly not devoid of meaning, however. It begins as a dream stimulated by Coleridge’s reading of Samuel Purchas’ 17th century travel book, Purchas his Pilgrimage, or Relations of the World and the Religions observed in all Ages and Places discovered, from the Creation unto the Present (London, 1617). The first stanza describes the summer palace built by Kublai Khan, the grandson of the Mongol warrior Genghis Khan and founder of the Yuan dynasty of Chinese emperors in the 13th century, at Xanadu (or Shangdu): In Xanadu did Kubla Khan A stately pleasure-dome decree Xanadu, north of Beijing in inner Mongolia, was visited by Marco Polo in 1275 and after his account of his travels to the court of Kubla Khan, the word “Xanadu” became synonymous with foreign opulence and splendor. Compounding the mythical quality of the place Coleridge is describing, the poem’s next lines name Xanadu as the place Where Alph, the sacred river, ran Through caverns measureless to man This is likely a reference to the description of the River Alpheus in Description of Greece by the 2nd century geographer Pausanias (Thomas Taylor’s 1794 translation was in Coleridge’s library). According to Pausanias, the river rises up to the surface, then descends into the earth again and comes up elsewhere in fountains -- clearly the source of the images in the second stanza of the poem: And from this chasm, with ceaseless turmoil seething, As if this earth in fast thick pants were breathing, A mighty fountain momently was forced: Amid whose swift half-intermitted burst Huge fragments vaulted like rebounding hail, Or chaffy grain beneath the thresher’s flail: And ’mid these dancing rocks at once and ever It flung up momently the sacred river. But where the lines of the first stanza are measured and tranquil (in both sound and sense), this second stanza is agitated and extreme, like the movement of the rocks and the sacred river, marked with the urgency of exclamation points both at the beginning of the stanza and at its end: And ’mid this tumult Kubla heard from far Ancestral voices prophesying war! The fantastical description becomes even more so in the third stanza: It was a miracle of rare device, A sunny pleasure-dome with caves of ice! And then the fourth stanza makes a sudden turn, introducing the narrator’s “I” and turning from the description of the palace at Xanadu to something else the narrator has seen: A damsel with a dulcimer In a vision once I saw: It was an Abyssinian maid, And on her dulcimer she played, Singing of Mount Abora. Some critics have suggested that Mount Abora is Coleridge’s name for Mount Amara, the mountain described by John Milton in Paradise Lost at the source of the Nile in Ethiopia (Abyssinia) -- an African paradise of nature here set next to Kubla Khan’s created paradise at Xanadu. To this point “Kubla Khan” is all magnificent description and allusion, but as soon the poet actually manifests himself in the poem in the word “I” in the last stanza, he quickly turns from describing the objects in his vision to describing his own poetic endeavor: Could I revive within me Her symphony and song, To such a deep delight ’twould win me, That with music loud and long, I would build that dome in air, That sunny dome! those caves of ice! This must be the place where Coleridge’s writing was interrupted; when he returned to write these lines, the poem turned out to be about itself, about the impossibility of embodying his fantastical vision. The poem becomes the pleasure-dome, the poet is identified with Kubla Khan -- both are creators of Xanadu, and Coleridge is apeaking of both poet and khan in the poem’s last lines: And all should cry, Beware! Beware! His flashing eyes, his floating hair! Weave a circle round him thrice, And close your eyes with holy dread, For he on honey-dew hath fed, And drunk the milk of Paradise. “Kubla Khan” is famously incomplete, and thus cannot be said to be a strictly formal poem -- yet its use of rhythm and the echoes of end-rhymes is masterful, and these poetic devices have a great deal to do with its powerful hold on the reader’s imagination. Its meter is a chanting series of iambs, sometimes tetrameter (four feet in a line, da DUM da DUM da DUM da DUM) and sometimes pentameter (five feet, da DUM da DUM da DUM da DUM da DUM). Line-ending rhymes are everywhere, not in a simple pattern, but interlocking in a way that builds to the poem’s climax (and makes it great fun to read out loud). The rhyme scheme may be summarized as follows: ABAABCCDBDB EFEEFGGHHIIJJKAAKLL MNMNOO PQRRQBSBSTOTTTOUUO (Each line in this scheme represents one stanza. Please note that I have not followed the usual custom of beginning each new stanza with “A” for the rhyme-sound, because I want to make visible how Coleridge circled around to use earlier rhymes in some of the later stanzas -- for instance, the “A”s in the second stanza, and the “B”s in the fourth stanza.) Sponsored Links HSC EnglishExtensive online resources designed exclusively for the English HSCwww.interactiveenglish.com.au Free A+ Study Guide (PDF)Essential Facts You Must Know. Instant Download, Get It Now!www.PrepLogic.com HSC - Get Ahead for 2009Free Study/Exam Skills Lecture Free Exams, Notes, Essays & Tipswww.tsfx.com.au Poetry Ads Narrative Poems Funny Valentine Poems Short Poems Humorous Poems Sorry Boyfriend Poems (Continued from Page 2) The Poem Notes on Context Notes on Form Notes on Content Commentary and Quotations “Kubla Khan” is a poem clearly meant to be spoken. So many early readers and critics found it literally incomprehensible that it became a commonly accepted idea that this poem is “composed of sound rather than sense.” Its sound is beautiful -- as will be evident to anyone who reads it aloud. The poem is certainly not devoid of meaning, however. It begins as a dream stimulated by Coleridge’s reading of Samuel Purchas’ 17th century travel book, Purchas his Pilgrimage, or Relations of the World and the Religions observed in all Ages and Places discovered, from the Creation unto the Present (London, 1617). The first stanza describes the summer palace built by Kublai Khan, the grandson of the Mongol warrior Genghis Khan and founder of the Yuan dynasty of Chinese emperors in the 13th century, at Xanadu (or Shangdu): In Xanadu did Kubla Khan A stately pleasure-dome decree Xanadu, north of Beijing in inner Mongolia, was visited by Marco Polo in 1275 and after his account of his travels to the court of Kubla Khan, the word “Xanadu” became synonymous with foreign opulence and splendor. Compounding the mythical quality of the place Coleridge is describing, the poem’s next lines name Xanadu as the place Where Alph, the sacred river, ran Through caverns measureless to man This is likely a reference to the description of the River Alpheus in Description of Greece by the 2nd century geographer Pausanias (Thomas Taylor’s 1794 translation was in Coleridge’s library). According to Pausanias, the river rises up to the surface, then descends into the earth again and comes up elsewhere in fountains -- clearly the source of the images in the second stanza of the poem: And from this chasm, with ceaseless turmoil seething, As if this earth in fast thick pants were breathing, A mighty fountain momently was forced: Amid whose swift half-intermitted burst Huge fragments vaulted like rebounding hail, Or chaffy grain beneath the thresher’s flail: And ’mid these dancing rocks at once and ever It flung up momently the sacred river. But where the lines of the first stanza are measured and tranquil (in both sound and sense), this second stanza is agitated and extreme, like the movement of the rocks and the sacred river, marked with the urgency of exclamation points both at the beginning of the stanza and at its end: And ’mid this tumult Kubla heard from far Ancestral voices prophesying war! The fantastical description becomes even more so in the third stanza: It was a miracle of rare device, A sunny pleasure-dome with caves of ice! And then the fourth stanza makes a sudden turn, introducing the narrator’s “I” and turning from the description of the palace at Xanadu to something else the narrator has seen: A damsel with a dulcimer In a vision once I saw: It was an Abyssinian maid, And on her dulcimer she played, Singing of Mount Abora. Some critics have suggested that Mount Abora is Coleridge’s name for Mount Amara, the mountain described by John Milton in Paradise Lost at the source of the Nile in Ethiopia (Abyssinia) -- an African paradise of nature here set next to Kubla Khan’s created paradise at Xanadu. To this point “Kubla Khan” is all magnificent description and allusion, but as soon the poet actually manifests himself in the poem in the word “I” in the last stanza, he quickly turns from describing the objects in his vision to describing his own poetic endeavor: Could I revive within me Her symphony and song, To such a deep delight ’twould win me, That with music loud and long, I would build that dome in air, That sunny dome! those caves of ice! This must be the place where Coleridge’s writing was interrupted; when he returned to write these lines, the poem turned out to be about itself, about the impossibility of embodying his fantastical vision. The poem becomes the pleasure-dome, the poet is identified with Kubla Khan -- both are creators of Xanadu, and Coleridge is apeaking of both poet and khan in the poem’s last lines: And all should cry, Beware! Beware! His flashing eyes, his floating hair! Weave a circle round him thrice, And close your eyes with holy dread, For he on honey-dew hath fed, And drunk the milk of Paradise. Charles Lamb heard Samuel Taylor Coleridge recite “Kubla Khan,” and believed it was meant for “parlour publication” (i.e., live recitation) rather than preservation in print: “...what he calls a vision, Kubla Khan--which said vision he repeats so enchantingly that it irradiates and brings heaven and Elysian bowers into my parlour.” --from an 1816 letter to William Wordsworth, in The Letters of Charles Lamb (Macmillan, 1888) Jorge Luis Borges wrote of the parallels between the historical figure of Kubla Khan building a dream palace and Samuel Taylor Coleridge writing this poem, in his essay, “The Dream of Coleridge”: “The first dream added a palace to reality; the second, which occurred five centuries later, a poem (or the beginning of a poem) suggested by the palace. The similarity of the dreams hints of a plan.... In 1691 Father Gerbillon of the Society of Jesus confirmed that ruins were all that was left of the palace of Kubla Khan; we know that scarcely fifty lines of the poem were salvaged. These facts give rise to the conjecture that this series of dreams and labors has not yet ended. The first dreamer was given the vision of the palace, and he built it; the second, who did not know of the other’s dream, was given the poem about the palace. If the plan does not fail, some reader of ‘Kubla Khan’ will dream, on a night centuries removed from us, of marble or of music. This man will not know that two others also dreamed. Perhaps the series of dreams has no end, or perhaps the last one who dreams will have the key....” --from “The Dream of Coleridge” in Other Inquisitions, 1937-1952 by Jorge Luis Borges, translated by Ruth Simms (University of Texas Press, 1964, reprint forthcoming November 2007) Prev