gastroenteritis

advertisement

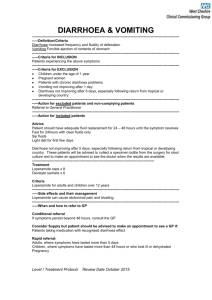

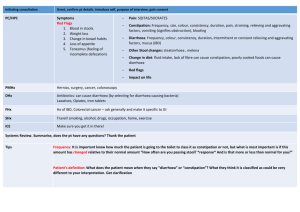

Block 8 Week 8 Acute infective diarrhoea : Gastroenteritis Tutor : Prof DF Wittenberg MD FCP(SA) dwittenb@medic.up.ac.za Objectives: To be able to list the causes and discuss the investigation and management of patients presenting with acute diarrhoea; know and discuss the epidemiology, aetiology, pathogenesis, pathophysiology, clinical features, diagnosis, complications and detailed management of patients suffering from gastroenteritis; Introduction It is estimated that on average every child will suffer from more than 2 attacks of acute diarrhoea per year before her 5th birthday. This means that an estimated 12 million episodes of diarrhoea occur in South African children each year. It is one of the commonest symptoms of disease, and also one of the most important causes of death. Illustrative Case Report : Johnny X You are asked to see young Johnny X because of a problem of high fever, severe vomiting and acute onset of watery diarrhoea. He is 8 months old and weighs 8.2 Kg. He attends a day care centre, where another child has had diarrhoea in the last week. One day ago he seemed to be well, but had a slight cough. After taking his bottle, he vomited all his feed, then developed a fever. Soon thereafter, his stools became loose, and then became very watery. At first, he was quite chirpy, but vomited after each bottle, even though he seemed to be thirsty and drinking quite fast. Now, he has become lethargic and pale. Mother has noticed that the soft spot on the top of his head is sunken in. His facial expression does not seem right. The stools are frequent, watery and greenish. Mother has not seen blood or slime. She is not sure whether he has any pain. Diarrhoea is a symptom of disease of the gut. Acute onset of diarrhoea as in the patient above is caused by Acute infection of the gut (acute gastroenteritis) Bacterial contamination of stored food (Food poisoning) A constituent of food of which the patient is intolerant eg laxative substance Task Review the causes and mechanisms of infective diarrhoea (C&W p 433 - 434) The most important effect of acute diarrhoea is the loss of water and electrolytes in the watery stools. Dehydration Water loss occurs initially from the circulation and all compartments of the body are affected because water moves instantaneously between compartments according to osmotic gradients. It is important to remember that the stool water in diarrhoea is not primarily derived from the oral fluids which the child may have been drinking. (Therefore it is not appropriate to withhold fluids or food in acute diarrhoea in the belief that the diarrhoea will then stop.) The loss of body water leads to compensatory mechanisms: Thirst Antidiuresis Catecholamine release of stress response Continuing water loss will result in failure of compensation, at which stage the patient enters a state of circulatory insufficiency. The clinical features of dehydration evolve in a continuous spectrum. Notes on the technique of dehydration assessment: 1. Look for signs of shock: Palpate the radial pulses. If they cannot be felt in a child, the blood pressure is most likely to be too low. Proceed to measure the blood pressure. Count the pulse rate. 2. Assess the level of consciousness and mental state, particularly the degree of alertness, apathy, irritability. Determine the muscle tone, especially in the upper limbs. Abnormalities point to decreased cerebral perfusion : consider giving oxygen 3. Assess the degree of clinical metabolic acidosis : rapid, deep breathing without evidence of lung disease. Often the mouth is pursed as if to get more air in : “Kussmaul” breathing. Count the respiration rate. 4. Determine the capillary refill time. On the heel or palm of the hand, squeeze out the skin blood to achieve a pale area of skin. Await and estimate the time to the flush of returning blood. The CFT up to 3 seconds is normal. Prolonged CFT shows that the skin capillaries are vasoconstricted : indicative of compensated shock and severe metabolic acidosis in a warm hand/foot. 5. Determine the skin turgor. Lift a fold of skin between thumb and forefinger perpendicular to the normal skinfold creases and let go, estimating how fast the skin returns to the smooth state. Choose an area of skin with adequate subcutaneous tissue, preferably where there is loose connective tissue. It is usually done on the anterior abdominal wall. Note that the skin turgor may be abnormal in patients with marasmus/wasting (“excess” skin leading to abnormal tension), in very fat babies (too little interstitial fluid between adipose cells, making assessment difficult), and in the presence of oedema. Severely decreased skin turgor 6. Determine whether the eyes are sunken into the orbit (loss of water from the surrounding loose connective tissue). The mother is usually the best person to assess this. Sunken eyes Acidotic breathing 7. Determine the moisture on the mucous membranes of mouth and eyes. Ask about urine output. A dehydrated baby has little tears and saliva. Each individual sign is not sensitive or specific, but taken together, one can determine the approximate severity in the following categories: Potential dehydration : Has diarrhoea, not yet clinically dehydrated. Usually no clinical signs Moderate to severe dehydration: Features of dehydration, no signs of shock. Signs 5 – 7 above are present. Severe dehydration, with features of compensated or uncompensated shock. Signs 1 – 4 are present. Management of Hydration If at the beginning of diarrhoea, mothers were to give their children as much fluid extra as they were losing in the stools, the children would not develop dehydration. Hydration management is therefore aimed firstly at maintaining hydration. This is achieved by allowing the child to drink extra clear fluid in small quantities (to avoid stomach distension and vomiting), as much as they want, after each loose stool. As the child has not yet lost much in the way of electrolytes, the specific type of fluid to be given at this stage is not critical: extra water is the issue. However, the presence of glucose and sodium improves water absorption (see C & W p 437). A dehydrated child needs electrolytes sodium, potassium and base (such as bicarbonate or citrate) in addition to glucose and water to replace losses. Now an oral rehydration solution is required. This is given at a rate exceeding the rate of loss, usually at 15 – 25 ml/kg/hour in small quantities at a time to avoid gastric overdistension and vomiting, until the patient is better, passing urine, wanting food. (C & W p 438) Once the child is so dehydrated that there is circulatory insufficiency, the patient must be resuscitated first before rehydration can take place. An isotonic solution such as Ringers Lactate is chosen and given intravenously to correct the circulating blood volume. (C & W p 438) Management of diarrhoea includes management of fluid losses as well as appropriate feeding Remember the sick gut does not tolerate foods in the normal way, or else there would be no diarrhoea. On the other hand, acute infective diarrhoea is a self-limiting condition and food changes are not indicated provided the patient is normally nourished. In general, a child with diarrhoea should receive its normal diet in small easy-todigest quantities and with some attention to short-term exclusion of high fibre, high fat/oil and meat (ie “tea and toast”, chicken soup, mashed potatoes, vegetables, paw-paw, bananas etc) and return to full usual diet within 2 – 3 days. Breastfeeding is the only type of food which can actually be increased during periods of acute diarrhoea, as breast milk has a low solute content and therefore is both food and hydration fluid! Other aspects of acute diarrhoea Task Review the other clinical complications of acute infective diarrhoea (C & W p 436 – 437) Drug therapy of acute infective diarrhoea The symptom of diarrhoea occurs after the infection has already happened and is a manifestation of its effect on the gut. Accordingly, antibiotic therapy does not shorten diarrhoea and is not indicated in the usual case. In any case, the majority of cases of diarrhoea are due to infection with viruses. Antidiarrhoeal medication is not indicated in young babies under 2 years of age, as these have most side effects and the antimotility effect of the drugs delays the rate at which toxins and bacteria are “flushed through”. Anti-emetic drugs have a central mode of action, where the vomiting is due to local factors in the stomach. Dehydrated children have a higher blood level of any drug than anticipated and tend to have more side effects. Case Analysis Johnny has an acute infection of the gut for the following reasons: Previously healthy and well nourished (weight 8.2 Kg at 8 months) Contact history with other children who had a similar disease in the recent past Acute fever with his disease On the basis of frequency and probability, he may have a rotavirus infection. The presence of cough is in support of this diagnosis. His symptoms suggest the presence of dehydration: Thirsty, drinking fast Lethargy Sunken fontanel He has acute gastroenteritis (possibly rotavirus infection) with dehydration He must be offered oral rehydration fluid, 120 – 150 ml per hour given by teaspoon in 10 – 15 ml quantities every 5 minutes. If he tolerates that and wants more, he can be given more. Once he passes urine, he can be offered about half his usual bottle of milk and a little porridge. Continue offering extra fluids after stools and for thirst. Review his clinical state in 4 – 6 hours for the presence of dehydration or other complication. Advise the mother on reasons to return or complications