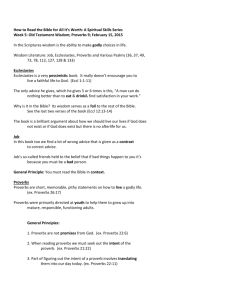

A Rhetorical Perspective on the Sentence Sayings of the Book of

advertisement