Sometimes Gladness

advertisement

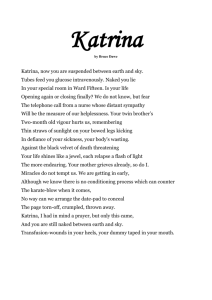

Sometimes Gladness By Bruce Dawe Teaching notes prepared for VATE members by Helen Howells 1. An introduction to Sometimes Gladness 2. Ways into the poetry Page 1 Page 2 3. A perspective on the poetry of Bruce Dawe Page 6 4. Organising a detailed study Page 8 5. Guided approaches to studying Dawe’s poetry Page 11 6. Activities for exploring the text Page 14 7. Appendix 1: Bruce Dawe at the 1999 VATE Conference Page 16 8. Appendix 2. ‘And Let the Last Word be with the Poet Himself…’ Page 19 9. Appendix 3: Teacher Record and Reflection sheet Page 21 Page numbers in these notes refer to Dawe, B. Sometimes Gladness, fifth edition, Longman, Melbourne 1997. VATE acknowledges and thanks Bruce Dawe for his assistance in approving notes made during his appearance at the 1999 VATE Conference and in granting permission for an earlier essay to be reprinted in this guide. VATE Purchasers may copy Inside Stories for classroom use Section 1. An introduction to Sometimes Gladness Bruce Dawe has had a significant place in Australian literature for most of the second half of the twentieth century. In all this time he has been a popular as well as a significant poet. His popularity rests in part on the accessibility of his writing. In some ways the assessment that Dawe is an accessible poet presents a difficulty for the teacher. If the reason for the popularity and the claim of accessibility rest on it being easy to make some sense of the poems on a first reading, then the task for the teacher will be to show the students that there is more to Dawe than meets the eye. Dawe’s childhood and adolescence were typical of those of many of the Australians of the Great Depression and post Second World War years. He was born in Geelong in 1930 and during the Depression his family moved around country Victoria and the inner suburbs of Melbourne. He attended inner suburban primary schools and Northcote High School but did not finish his secondary schooling at this time. A description of the various jobs he had before joining the RAAF – clerk, salesman, laborer, office boy, farmhand, factory worker, postman – points to a likely source of the colloquialisms and understanding of ordinary Australians of the fifties and early sixties which are so much part of his poetry. His first collection of poems was published in 1962 by F.W.Cheshire. One of the most interesting ways into Dawe’s work in Sometimes Gladness is to read the poems in the order set out in the anthology without looking for themes or examples of different forms or any other unifying device. The sense of his interest in every aspect of the human condition that comes through when this is done is striking. By not focusing on only the most well known poems, a greater understanding can be developed of Dawe as a writer for whom writing seems to be an integral, natural part of the business of living. To Dawe, if a person, an event, an idea exists then it is the stuff that writing is made from, though it must be said that not all attempts are equally successful. The other result of reading through the poems as they are presented, is that the diversity and range in Dawe’s writing style makes an immediate impact. Different poetic forms follow one another, there are different rhythms and speech patterns from one page to the next. Through it all there is a celebratory affinity with many of the people in the poems and a recurring humour which counter-balances the kelp-like ‘larger darknesses’ of other poems. Reading the references on Dawe is to read the development of literary theory over the last half century. The VATE booklet BRUCE DAWE: The Man Down the Street 1 first published in 1972, contains articles written in the sixties which seem to make the discussion of Dawe’s poetry a relatively straight-forward matter. To then read Peter Kuch in his book BRUCE DAWE 2saying that with post structuralism, there are new ways of reading Dawe, is to realise that times have changed. For a poet like Dawe, the change is liberating. 1 Hansen, I.V (ed) BRUCE DAWE: The Man Down the Street for the Victorian Association for the Teaching of English, Melbourne, 1972 (Out of print) 2 Kuch, Peter: BRUCE DAWE, Oxford Australian Writers series (OUP, Melbourne, 1995) VATE Inside Stories Sometimes Gladness 1 Section 2. Ways into the poetry A small group approach After a brief reference to Dawe as a contemporary Australian poet, divide the class into small groups and give each group a different poem to read and respond to. You may wish to use poems that have common thematic links, those that are representative of the different poetic forms that Dawe uses, or you may wish to use poems that do not have any particular connecting links. After some time check to see what the students have made of the poems within their groups and ask each individual to make a brief journal entry. Then ask some questions or add some information that could assist students to deepen their response. Give the students time to respond then ask each group to prepare a list of the questions they still have about the poem. These could be submitted to you to assist in planning for the next session. When the students are happy with the understanding they have developed in their group, ask them to prepare an oral presentation on the poem. This should result in a further round of discussion as the demands of the task might reveal new meanings or raise new questions. Each group should present its reading and there should be time allowed for questions and comments from the whole group. There will probably need to be considerable amount of time allowed for students to make annotations as they respond to all the presentations. A worksheet to accompany this activity is provided at the end of this section. Creative response “Mrs Swipe Speaks Out” Using this particular monologue would provide a fine way of introducing the study of poetry for a group which seems a little hesitant. Prepare by deciding on the reading style you will adopt in your presentation to the class and by rehearsing the reading carefully. Introduce the poem by asking students about the things which cause neighbours to have disagreements. Then read the poem. Build up a picture of the kind of person Mrs Swipe is, by reading the last six lines again and discussing them by looking at the words in italics and by describing the ‘way’ in which Mrs Swipe speaks throughout the monologue. Now have the students look for any evidence in the poem which could be used to build up a picture of Mrs Swipe’s neighbour. Working in pairs they could read the poem again and make notes about the neighbour’s character. Then, still working together. The students could write a response “ Mrs Swipe’s Neighbour Answers Back”. Now suggest to the students that they imagine a situation in which they have a difference with their friend or a member of their family over something they want to borrow. Ask them to write a monologue using their own voice and speech rhythm. This poem is a good example of those poems of Dawe which are easy to leave after a couple of readings but which repay further study. Students could discuss the reasons for absence of punctuation; the colloquial tone, ‘..you’ve got another think VATE Inside Stories Sometimes Gladness 2 coming’; the mixing of sayings, ‘..every worm must have its day’; the energy of the spoken words; the attitude of Dawe to his character Mrs Swipe (and also although she does not appear in person, to her neighbour); the way in which the liveliness of the characters is established. A ‘spaced out’ study Bruce Dawe is a good poet to read a couple of times each term before reading and studying the larger selection of his poems which is more representative of his work. Reference could be made to Dawe as a very popular Australian writer, a poet who people find accessible and one who frequently writes about everyday people and events. The poems chosen for each session could have something in common, for example the same form or the same theme. Or, the poems chosen could provide a contrast belonging either to the so-called ‘public’ or ‘personal’ poems or the poems chosen could be written in different styles. Groups of students could take turns to present the poems chosen for the sessions. Records would need to be kept and this could be done using a journal and profile sheets. (A sample Profile Sheet is provided at the end of section 4.) Dawe on poetry If the students have already studied Dawe or they have been used to reading poetry in English classes you might like to commence the Units 3 and 4 study by focusing on Dawe the writer for a while. Poems could be chosen which fit in with this approach. Dawe’s introduction to Sometimes Gladness looks at two questions ‘Why write?’ and ‘Why publish?’ The responses to the questions are easy to read and could be followed up by reading “Presences” or “Interviewing a Poet”. The VATE publication, BRUCE DAWE: The Man Down the Street,3 has an interesting essay in which Dawe writes directly to students. (It is reprinted as Appendix 2 in this publication). He responds to three questions about his outlook on life, the place of the poet in Australia and what he is trying to say. He concludes with a paragraph where he discusses his view that ‘a poet is a person like any other’. After reading the essay students could look at the title poem “Sometimes Gladness” pvii, “Two Ways of Considering the Fog”, “A Warning to Young People”, “Intersection”. BRUCE DAWE: The Man Down the Street also contains an excerpt from Dawe’s Commonwealth Literary Fund Lecture, 1964 where he refers to ‘speaking for those who cannot speak for themselves’. Poems like ”No Fixed Address”, “Old Harry” and “Up the Wall” could be related to his comments. Poetry reading Using taped readings of the poetry can deepen the impact of the first reading of a poem especially if you can persuade other members of staff or students from other English classes to read the poems for you. You may want to have the students listen to the tape and make responses about the mood or tone, before they read the poem. Discussion of the what the poem is about is probably easier after the students have read it for themselves. 3 Hansen, I.V. op cit VATE Inside Stories Sometimes Gladness 3 Dawe enjoyed reading his poetry at public gatherings. Students listening to the tapes of his readings may find new insights into the poems. Details of tapes of Dawe reading his own poetry are listed by Peter Kuch in the bibliography of his book, BRUCE DAWE4 4 Kuch, P. op cit VATE Inside Stories Sometimes Gladness 4 Format of worksheet for use in a small group activity Section 2 GROUP DISCUSSION WORKSHEET Names of group members: Title of poem: Questions for presenters: Answers and comments from presenters: Connections that can be made to the poem my group presented VATE Inside Stories Sometimes Gladness 5 Section 3. A perspective on the poetry of Bruce Dawe It is not easy to come up with statements that will provide a neat description of the kind of poet Bruce Dawe is. “Weapons Training” and “Beyond Sunrise” are poles apart. The kinds of language used across the poetry has a great variety and the poems range from those that are deeply personal to those that are about issues of national and international concern. Dawe’s own statement that he does not have an overview ‘a synthesising view’ is some justification for not trying to impose the description ‘the poet’s outlook’ on him, even if he has gone so far as to say in the same article that there is ‘one sky over all of us’. A People’s Poet Everyone comments on Dawe’s popularity as a poet. The number of editions and reprints of Sometimes Gladness is proof enough. His popularity seems to have something to do with the fact that Dawe is seen as a people’s poet, a ‘democratic’ writer. He writes of the people – a boy playing truant from school, itinerant workers, his daughter, recruits in the army, barrackers at the footy, quarrelling neighbours, oppressed people. In choosing to use a conversational style, the cliches of speech and the colloquialisms of the street you could almost say that his writing is done by the people. He takes over the very phrases of the street – ‘Agnes crack(ing) it for a smile’ in “True Believers”, the description of death in “Going”, ‘Mum, you would have loved the way you went’ and ‘Life’ being described as ‘a bit of a bastard’ in “After you, Gary Cooper….”. Of course, this aspect of his work is deceptive because its very accessibility can disguise the underlying strands of allusion and memory in the language of the poems. In his attitude to the subjects of his choice Dawe is writing for the people. He takes ordinary people in both their everyday moments and their moments of significance and he gives them a new significance. Dawe’s people are not heroic. Dawe does not aim for the transfiguration of his subjects. Dawe has observed ordinary people and in writing about them, he gives them a public space. He writes of their universality and that allows them to speak for the people they belong to. This is Dawe writing for those who cannot speak for themselves. These people could relate to Shagger’s mates, Old Harry, the recruits in “Weapons Training”. However, Dawe does not have the same attitude to all those he writes about. He might write about politicians, academics, church leaders but it is often to point to the failures, not to see in them a common bond. However, this does not let the rest of us off the hook. Dawe does not have uncertainties about his views of right and wrong. Neither does he have any doubts about the way we are all implicated in the wrongs. Universality applies to the good and the bad. Dawe’s own comments at the end of the introduction to Sometimes Gladness are about ‘universal experiences’. As citizens we are all party to the horror being described in “A Victorian Hangman Tells his Love” as well as being readers who are horrified by what is being done. The anonymity of the repeated ‘They’re’ in “Homecoming” allows us all to be in part responsible for what is happening. VATE Inside Stories Sometimes Gladness 6 And the way he says it To read the titles on the first page of Sometimes Gladness is to become aware immediately of Dawe’s particular kind of humour. Titles such as “Enter Without So Much as Knocking”, “ A Good Friday Was had by All” and “After You, Gary Cooper…” are a preparation for the ways Dawe plays with language and humour to put his reader in the position that he wants Humour is also used to cut things back to size, to make a point against the people who want to be arbiters of what should happen, people like the Councillor in “Pigeons Also Are a Way of Life”. “Any Shorter and I’d Have Missed it Altogether” is another poem that belongs to that group which present the self-deprecating and unselfconscious humour of the street. The question does arise whether the frissons of recognition in the colloquialisms will work for everyone. There may be a danger in that the appeal of poetry that catches the language of the street for one generation may date and later readers will be unable to enter fully into the poet’s language. “Uh-huh…So that’s what the so-and-so really thought, hey?” Instead of trying to trawl through the standard thematic approach, it is possible to take a couple of the most well known poems, look at what they are saying and use that as a way of exploring concerns that might not properly be described as themes. For instance, the poem “Towards Sunrise” is Dawe’s gentle description of a flight during which a woman sitting beside him, fell asleep with her head resting on his shoulder. In the last half dozen or so lines he looks at the fragility of the experience, contrasting it with the physical reality of being ‘buckled in’ as if by starlight. The encounter has found its place as a defining moment when Dawe draws our attention to the need to recognise fleeting experiences of the beautiful, the transcendent. Dawe has looked at the same notion in the poems “Intersection” and Presences”. It is there, perhaps obliquely, in “Home Suburbiensis”, “Drifters’ and “My Experience of God”. Dawe is also concerned to explore the ways in which the individual is constrained, controlled and deprived of freedom. The poem” News From Judea” is about the attempts in Queensland in the 1970s to stifle public protests. It looks at the way in which the quiet that comes from oppression is not the quiet of peace. The authoritarianism, hypocrisy and arrogance satirised in the declamatory statements from Herod and Tiberius in this poem are denounced in poems like “At Mass” where the right to speak out is being defended against a church in which the ‘Word’ is ‘snap-frozen’, in “Open Invitation” or “You Too Can Have a Body Politic Like Ours if You’re Not Careful” and in poems about Vietnam and the states of Eastern Europe. Furthermore, Dawe’s criticism goes beyond church and state reaching out to the arrogance implied in the ‘totalitarianism of the banal’ in “On Bad Days”. Even though Dawe has a rather energetic ‘outlook on life’ as described in his article from the VATE booklet, the darker side of life is never far away. It may be the darkness of no one really listening as in “Up The Wall”, or the darkness of “ And A Good Friday Was Had By All”, and “News From Judea”. The man in his suburban garden gives as part of his offering, ‘pain…hate…war…death…fever…’. However, Dawe does not indicate any interest in opting out. Rather, in the last stanza of the title poem "Sometimes Gladness" he says “‘There is nothing in life as beautiful as life…’?” VATE Inside Stories Sometimes Gladness 7 Section 4. Organising a detailed study Students will need to use some system to organise the material they produce during their detailed study of Dawe’s poetry. The system should assist them with cross referencing, provide a manageable set of notes for revision and facilitate the development of a coherent overview and understanding. The following are three suggestions for strategies which could be used by the students: A poetry journal or log book Profile sheets Annotation sheets A poetry journal or log book By keeping a record of the work done, the student should be able to develop a sense of continuity in the study. The journal or log book might focus on the sort of work done in the classroom without making detailed comments on individual poems, might contain strategies that that proved most helpful in developing responses to the poems and it could include notes on class responses to Dawe’s work. At the back of the journal there could be a list of articles, notes on references, handouts, worksheets and other such material. The record in the journal could be a narrative of the development of the student’s understanding of Dawe’s work. At the end of each term the student should read the journal entries, re-read the poems studied and their profile and annotation sheets and then write a short response in the journal. The response could include; comments on the development in the student’s perception of Dawe’s poetry to this point; the changes since the last short response; those features of Dawe’s poetry that are most significant for the student; those particular poems which the student sees to be the most important in the study so far. Ideally the journal should be the place where those notes are made that are to be the basis for the overview that the student finally achieves. Profile sheets Profile sheets provide an on-going record of students’ responses to individual poems and a record of work done during the study. If a separate sheet is kept for each poem studied, then it is easy to extract particular poems for cross referencing when work is being done on themes or genres or any other common aspect across poems. Keeping an adequate record of work is especially important if the poems are to be studied at various times throughout the year. It is also useful to have the poems on separate sheets because it makes it easy for the student to add to their records. Using separate sheets puts an emphasis on the reading and enjoyment of the poems themselves. Work on themes should arise from the continuing study rather than being used as an organising strategy from the outset. Structure of the Profile Sheet handout The space for comments after the first class lesson allows for the important initial response without requiring a full scale analysis. The section ‘continuing detailed VATE Inside Stories Sometimes Gladness 8 study’ allows for comments to be added whenever more work is done. The ‘single sentence statement’ is intended to give the student an easy way of referring to the poem without becoming involved in ‘telling the story’. It would therefore be worth taking the time to check that students have really developed an accurate, succinct statement. (Format of Profile sheet provided on next page). Annotation sheets For particular poems it is worthwhile having the poem photocopied on one sheet and making annotations around the poem. The following notes could be used to help students to get started with their own annotations. Obviously teachers could add their own starting annotations. Drifters p94 The title says so much but is it all?…the woman still takes positive action ‘picks’ tomatoes, ‘notices’ the eldest girl ‘puts’ the bottling set on the trailer…the density of meaning in the last line – wishful thinking, longing, resignation, what would she wish, he wish?…the shadowy yet powerful presence of the man ‘he’ll tell her’ ….only the man has a name…the image of the four people and the dog. A unit yet five separate creatures…the simplicity of the language, the single syllables of the first line. My Experience of God p 239 Transcendence of title contrasts with colloquial, enigmatic ‘I’m going to have to pass (on)…the contrast of ‘invitation’ line 2 with ‘invite line 6,…first response to meaning of ‘father’, who is poem addressed to really?…flamboyance of images; meteor showers, Burning Bush, wedding in Darjeeling, contrasts with self deprecating ‘I just about had it off perfect’…is he chiding the priest for the concept (experience of God) but not for asking?…’sat around waiting’ does this imply that this is not the way these things happen? News from Judea p177 Use of the style of the King James version…Herod-Joh Bjelke-Peterson, TiberiusMalcolm Fraser…satirises the law and order arguments…sense of foreboding in last two lines…dramatic slowing down of pace with colloquial ‘And they did just that’…use of italics for speech gives impression of proclamation…political significance of ‘detention without charge and also incrimination by silence’…’brought before the courts’ Dawe’s own part in the demonstrations. The Cornflake p170 Free verse…opening lines as if this is to be a classical piece…grotesque image of the cornflake in the gullet…moves back and forth between eccentric/conventional images; tragedy/absurd, autumn leaves/ city, balletic/ rattling, cornflake/ snowflake… intelligensia/ infants…ellipsis means there is no end to the ideas…poet playing with his reader? Pigeons Also Are a Way of Life p25 Importance of ‘also’ in the title…the narrator is a critical observer…the city Councillor is being observed…irony in ’permitting pigeons’ …the pretentious language is used to position the reader against the Councillor ‘testimony’, ‘concurrence of light’…what is the real reason for the Councillor’s intention? VATE Inside Stories Sometimes Gladness 9 PROFILE SHEET Title of poem: Page: First reading: date My immediate response: What was significant for me?: Questions I have about this poem: Continuing detailed study The central idea of the poem (One sentence) Date of the poem: Poetic form: Background information: Significant features of this poem: (comment on any of the following features that are relevant to this poem – speaker, language, tone, humour, imagery, structure, attitude of the poet, the poet’s position on the issue in the poem, my position on the issue and its effect on the way I read the poem) Detailed description of the content of the poem. Themes: Cross references to other poems VATE Inside Stories Sometimes Gladness 10 Section 5. Guided approaches to studying Dawe’s poetry A thematic approach There are a variety of ways of grouping Dawe’s poetry according to theme. First, the poems can be grouped using the eleven themes used in the Longman edition of Sometimes Gladness. The categories are extremely broad and the poems are listed under several themes where that is appropriate. Dawe has given his own comment about the kinds of concerns that he writes about. In the introduction to Sometimes Gladness he says he is concerned about ‘what it is like to be in love, or in a war, or in a city, or in a dream’. These four categories could provide a smaller group of themes. An approach using Dawe’s views about writing Bruce Dawe says that he has often been asked why he writes. And he has also said that in the end, the answer that one must come back to is’… because one feels like it’. However, Dawe has made other comments about writing and his own world view. His following comments could be used to provide a unifying approach to the study of the poems: ‘…there are the lost people in our midst for whom no one speaks and who cannot speak for themselves.’ 5 (Individuality) ‘is always under attack somewhere in the world, and always somewhere (thank God) defended.’6 ‘There is nothing in life as beautiful as life.’7 ‘…publishing poetry ..helps us to see ourselves and our world more clearly.’8 ‘.my outlook on life..I see it as confusing, bloody, tremendous, meaningful, sad, hilarious, deadly and quite unique…I don’t have the overall synthesising view which ties it all up neatly…so that when you read the collected works you can say “Uh-huh …So that’s what the so-and-so really thought, hey?”’9 A question and answer approach 5. Excerpt from Commonwealth Literary Fund Lecture, 1964 in BRUCE DAWE: The Man Down the Street 6 Sometimes Gladness pvii 7 ibid 8 ibid pxvii 9 BRUCE DAWE: The Man Down the Street p 50 VATE Inside Stories Sometimes Gladness 11 The handout on the following pages is intended to provide students with an approach that can be used for any poems they choose to read and study. It is a way of encouraging students to read poetry on their own. Structured questions Use these questions to assist your study of selected poems Title of poem: TITLE: What indication about the meaning of the poem is given by the title? Is it easy to tell from the title what the poem will be about? Does the title raise questions or give answers? VOICE: Who is the speaker in the poem? Is the poet speaking in his own voice? Has the poet used the voice of a character in the poem? Is the poet an observer? Is the poet seeking to persuade the reader? What devices does he use? CONTENT: What is the speaker saying? Is there a particular audience for the speaker? Is the reader part of the audience? VATE Inside Stories Sometimes Gladness 12 Structured questions (cont) TONE OR MOOD: How is the poet feeling? Is the poet happy about what he is writing about? Is the poet angry about something? Is the poet using humour to make a point or is the poet using humour because the poem is about something amusing? Position of the poet. Is the poet sympathetic to his subject? Is the subject matter of the poem a public issue? Is the subject matter a personal concern of the poet? Is the poet leaving his readers free to make up their own minds about the issue or concern? Theme. If the poem has a theme, how would you describe it? List any other poems by Dawe which also have this theme. VATE Inside Stories Sometimes Gladness 13 Section 6. Activities for exploring the text Listening, speaking, reading Prepare three poems to be read to an audience which does not know Bruce Dawe’s poetry. Which poems would you choose? What reasons for your choice would you give when you introduced the poems to your audience? Would you make any introductory comments about Dawe? What would you say? When would you say it – at the beginning of the session or at some other time? These are some possibilities for an audience: Year 11 students who have indicated that they are thinking of doing Dawe in 2001, a CAE group who would like to hear what VCE students make of Dawe’s poetry, a VCE Art class which has decided to use some poems of Dawe as the starting point for a folio piece. Read “A Footnote to Kendall” (p243) and “Kidstuff” (p240)in Sometimes Gladness and “For Heidi with Blue Hair” (p103) and “Chippenham” (p104) in Four Women Poets.10 Working with another student discuss the relationship between the poet and the speaker in each poem. Discuss the poets’ views of what it is like to be young in these poems about children and young people. Choose a poem that has not been studied in class and prepare a case for writing up this poem on a profile sheet. Plan to take a couple of minutes to present your case to the class. Look at the concerns which Dawe describes in the fourth paragraph of his introduction to Sometimes Gladness. Working in small groups, discuss the poems you would list under each theme. Prepare to read “ Homo Suburbiensis” to a small group of students in your class. Each student in the group should take a turn to read the poem. As the poem is read, listen for differences in meaning which indicate possibilities for an interpretation other than your own. Discuss your responses to each reading in your group. Writing It helps you to see the way writers achieve the effects they want if you try writing yourself. Start by writing about a ‘character’. First read about some of the characters presented by Dawe in, for example, “Weapons Training”, Mrs Swipe Speaks Out”, “The Busker Outside Piggots”. What kind of people has Dawe presented? Then try writing, in poetry or prose, about a ‘character’ you have known or observed. Did you have an idea about what you wanted to achieve before you started or did the idea emerge as you wrote? When you are reasonably happy with what you have written, ask someone to read your piece and ask them what they thought the piece was about. See the extent to which it matches up with what you had in your mind. But also listen for ideas that your reader found were not part of your intention. Discuss the way this could happen. You might like to read “Presences” to complete this activity. 10 Baxter, Judith: FOUR WOMEN POETS, Cambridge Literature series (CUP, Great Britain, 1995) VATE Inside Stories Sometimes Gladness 14 At the conclusion to his introduction to Sometimes Gladness, Dawe discusses the ways in which it is important for a poet to ‘go public’. Dawe has often ‘gone public’ on issues of community concern such as Vietnam, the occupation of the Baltic states, capital punishment, ethnic cleansing, East Timor, environmental degradation. Choose a poem that takes up such an issue and write a review which describes the way in which Dawe presents his point of view. You should discuss not only the ideas in the poem but the way in which features such as humour, irony, imagery and others have been used to achieve the effective presentation of Dawe’s point of view. Prepare and write out a list of suitable questions you would ask If you had the opportunity to interview Bruce Dawe to get material for the following writing tasks: - An article for the school magazine - An essay on “A Victorian Hangman Tells His Love” - A letter to an overseas penfriend in response to a letter asking what Australians are like. Write a short statement about what it has meant to you to have read and studied Dawe’s poetry. In your statement you should try to write to develop an engagement between you and your reader. To achieve this, you will need to emphasise your own responses to the poems and you will need to support the claims you make with the examples that you see to be the most effective. Then write an appreciation of Dawe’s poetry in which you try to give a sense of what Dawe’s poetry is all about for someone who has not read his poems. You might try to reflect some of the qualities in Dawe’s own writing, for example, his use of everyday language, his easy going style, his humour, the strength of his concern for important issues. Find a copy of Kenneth Slessor’s poem “Beach Burial”. Read the poem, preferably out loud, then jot down your ideas about the poem. Now read Bruce Dawe’s “Burial Ceremony”, again reading aloud and jotting down your ideas about the poem. Plan a piece of writing in which you compare the two poems. You should plan to include references to the tone, the voice of the speaker, the imagery, the style of writing, the rhythm of the lines, what the poet is saying, the point of view of the poet and any other features that arise from the comparison. Using the plan you have developed write a short piece, setting yourself a time limit. Topics for extended writing 1. Dawe’s poetry shows a deep distrust for authoritarianism of any kind. Discuss. 2. The characters in Dawe’s poems may not be heroic but they are credible and they evoke strong responses from the reader. Discuss this claim by referring to three or four poems. 3. The strength of feeling is evident in poems such as “Homecoming” and “News from Judea” However, there are other poems which have strong feelings but of a different kind. Discuss. 4. Dawe’s colloquial style of writing is his trademark, but it should not lead the reader to underestimate the seriousness of what he is saying. Discuss. VATE Inside Stories Sometimes Gladness 15 Appendix 1. Bruce Dawe at the 1999 VATE State Conference Bruce Dawe was the speaker at one of the Conference Breakfasts and at a Meet the Writers session. The following are some notes made by Helen Howells during those two events. (The notes have been read and approved for publication by Bruce Dawe.) At the Conference Breakfast - Dawe read the sonnet “Up the Wall” and commented that it was a companion piece to some of Gwen Harwood’s poems. When Dawe read the poem “A Victorian Hangman Tells His Love” (p79) the softness of his voice had a chilling quality. You ‘saw’ the hangman standing close behind his subject and heard the whispers. The reading underlined the barbarity of this love poem. - In response to questions about his ‘philosophy of life’ (which he keeps being asked) he said that it is to ‘stay confused’. If you are uncertain it may mean that you can learn something. Closed minds do not learn. - In introducing “Mrs Swipe Speaks Out” Dawe said that he had in mind the ‘beefy’ type of people in Orwell’s 1984. He also referred to the way that he likes to listen to conversations. - Talking about the political concerns in his poetry, Dawe said that he is bemused by the venality of people. For him, the heroes are people like those who tried to get rid of Hitler. Political Science was the most interesting part of his studies. - In response to a question about the advice he would give to young poets, Dawe said his advice is to keep reading. Poetry writing never gets to be plain sailing, it does not reach a plateau. You need to keep reading and informing yourself about what the possibilities for writing are. Don’t worry about not having ‘a voice’. He referred to the description of free verse as being like playing tennis with the net down. Writers need to stretch themselves. They will develop skills if they see what others have done, if they go back over what they have read to see what else is there. - Dawe was asked to comment on his own poems by saying which ones had made the biggest impact on him. He said he did not know and that he tended to look ahead rather than look at his poems in that way. He also spoke about the image of the poet and the way in which there is a stereotype, supported by films, of the corduroy-clad individual. His own approach to writing was not highly disciplined and did not take up a lot of his time. - The poem “A Sense of Commitment” satirises the post-modern approach to commitment through a monologue with Eve as the speaker. After the breakfast Dawe discussed the title poem in the fifth edition of Sometimes Gladness. He said that he was exploring the two strands of meaning in the quote from G.K.Chesterton. VATE Inside Stories Sometimes Gladness 16 At the Meet the Writers session During this presentation Dawe started by reading and commenting on several poems in Sometimes Gladness: - In discussing “Santa Cruz” Dawe described Australians as not qualifying politically as being brave or being ‘democratically committed’. The poem is a critique of our moral cowardice at a political level. - “Big Jim”. There had been a great deal of laughter when he read this poem. He had enjoyed the reading and later in response to a question he described the Phelan family as being very dear to him. - “Interviewing a Poet” Dawe read this poem and referred to an occasion when he had been interviewed and had not found it a satisfactory experience. Dawe again referred to the way he enjoyed listening to conversations and picking up their flavour or reading material that had a style of its own. He received great satisfaction from imitating through parody. He spoke of the distinctive ‘kind of lingo’ that is typical of race broadcasters and the Safety Features cards in aeroplanes. He had written about safety features for a ‘Nemesis Airlines’ which concluded with a question about whether you might have a better chance of survival if you panicked. There was quite a long comment about “Road to Londinium”, the final poem in Sometimes Gladness. Dawe started by discussing the One Nation phenomenon, pointing to the reasons why Pauline Hanson gathered such support but also alluding to the dangers in her approach. The poem used the story of Boadicea to present a picture of Hanson’s campaign through Queensland. In his reading about the history of Britain under the Romans, Dawe had found the similarities in the passage of events was striking. He was taken by the way in which the Romans had seemed to be tardy in taking issue with Boadicea just as Howard had been tardy in taking issue with Hanson. (The lines in italics in the poem refer to this). His last comment was that sometimes things that seem to have something going for them are ‘ash’. A comment on: - Republicanism – it looks to be dying out. - The flag issue – the flag will carry an enormous weight as a symbol. - The Preamble – a poison chalice. There was warm appreciation in the laughter that followed a request that Dawe read “Life Cycle”. Dawe himself obviously enjoys the poem and his reading accentuated the humour. His quivering ‘Carn…carn..’ at the end brought the house down. He talked of his love for the sport and the way the footy scarf was the epitome of the fans’ loyalty. The idea started with the notion of children being born into a barrackers’ culture as presented in the first three lines. - “At Shagger’s funeral”. Dawe spoke of a funeral where one of the mourners had never been to a funeral before and sat in the front row. He referred to people having the experience of being totally out of place. The sense of mateship had brought them there. - “Homecoming”. Again there was a strong response to Dawe reading the poem. The images come from the Tet Offensive. Dawe spoke of the Vietnam memorial in America, its simplicity as a memorial and the fact that it had been funded by a public appeal. VATE Inside Stories Sometimes Gladness 17 - In response to a comment about the significance of death in his poems, Dawe said that death was a part of life but he wrote poems that he thought were lifeaffirming as well as poems that seemed to focus on death. - About unemployment. Dawe said that the unemployment figures were down because people had given up on the search for work or the figures have been fudged so that being employed for one hour a week, which is not really to be employed at all, is counted as if it is. (See the poems “Unemployed” and “Doctor to Patient”). The session concluded with more questions about why Dawe wrote poetry and his ‘philosophy of life’. Dawe made the following comments: - ‘I do not write to change things, but to say what I think and feel about them’. - ‘People say to me that they relate to a poem and what it is saying…I deal in terms of my first audience first and that is myself …I write as I write, I do it because I enjoy it, it is meaningful to me’ - ‘ I haven’t got a philosophy of life except, stay confused’. VATE Inside Stories Sometimes Gladness 18 Appendix 2. AND LET THE LAST WORD BE WITH THE POET HIMSELF......... This essay was originally published in BRUCE DAWE: the Man Down the Street: VATE publication, 1972. Bruce Dawe has kindly given permission for the essay to be reprinted here. It gives me great pleasure to contribute to this commentary on my work, since I vividly recall my own schooldays in Victoria and the need I felt for some assistance to my own understanding of other poets. I never aimed at being a burden to students, and if I can in any way assist those responsible for this pamphlet in easing any such burden, I will be only too happy. Firstly, my outlook on life... Well-l-l...I see it as I guess most people do, as confusing, bloody, tremendous, meaningful, sad, hilarious, deadly and quite unique. And I find it therefore always just beyond where the typewriter keys are hitting this moment. Let’s see: it’s as if you were hauled out of bed in the middle of the night and (before you had regained your senses) you suddenly found yourself standing spot lit, in the top half of your pyjamas on the back of a truck which was proceeding slowly through the streets of some weird town where the local brass band was blaring its loudest while from the crowd of spectators came a steady fusillade of ripe tomatoes, bon-bons and the odd handgrenade. I mean ---- it’s unforgettable, but --- how will you tell the folks back home? And --- if you did tell them --- how would they believe you? That’s how I see life, in general terms. In other words, I don’t have the overall synthesising view which ties it all up neatly so that when you read the collected works you can say: “Uh-huh . . . So that’s what the so-and-so really thought, hey?!” When I was around fifteen I used to have this weird thought over and over again that it was only an accident that I wasn’t starving to death in Poland or blown to bits in Russia or Germany, and I never really got over the terrible implications of that single fact. (I mean I know I should have, and all that, but I didn’t, and if I had to put a finger on a single thing which seems more significant in my early life than any other, I’d say it’s that one grievous idea: that the one sky is over all of us, the one earth underneath our feet.) The place of the poet in Australia today? Insofar as there is a place in a bull-necked civilization like our own for poets, that place I believe is at the barricades, fighting alongside those others who feel it part of their responsibility as citizens to resist those who would turn Australia into a quarry-hole surrounded by an oil-slick, those who imagine we have a future in a world where most never have a square meal or a decent bed or good health while we do so little about it, those who have demeaned politics to the level of Fred Flintstone in the constituency of Bedrock, those who have made a profession of serving two masters. There are many ways of expressing what one cares about it: it would be very hard today to be a poet and not try to express, however inadequately, some of the concerns that are ours as citizens. To this extent, I would agree that the times are revolutionary and that we should be citizen-poets as the soldiers of Revolutionary France called themselves citizensoldiers. I think we should aim at being blue heelers and not lap-dogs, as the country VATE Inside Stories Sometimes Gladness 19 and its fortunes demand we should. There are things to sing for pure joy about, the elemental things we share with all mankind, like love, friends, breath --- and there are the things we should use what voice and skill we have to rage about, but that, too, can be positive, a lament for a vanished or vanishing good ... Which leads on to the third question: what I am trying to say myself? Inasmuch as art gives us experiences, keeps us aware of the possibilities of life beyond those we have so far encountered as well as enriching our past and present experiences, I guess this is what I am getting at. I am trying to put down at least some of my feelings and impressions about various things, to pluck them out of the flux of the space-time continuum, isolate them, fix them on the page so that I can say: “There . . . that’s a bit of it (or almost)!” And the page becomes a hand holding it up where I can see it, and where (sometimes) others can see something of the same beauty, ugliness, comedy, sorrow as I say there --- just as the writers who impress me are the ones who do this, too --- who make things real in new ways (as for example, Ted Hughes makes the world of nature multi-dimensional in his poems like “The Bull Moses”, “Ester’s Tom-Cat”, “Pike”, “The Jaguar”). Finally, I would like to stress the fact that a poet is a person like any other. He may well be the postman with his whistle, the labourer leaning on his shovel on the building-site dreading the day they invent rubber-handled shovels, the gardener next door, the clerk across the street, the father strolling in the park with his kids, the bloke at the footie screaming his lungs out, the teacher who (rumour has it) “writes a bit”, the Byronic Wildean archetype (these days in TV series usually summed up nicely as a sad or Machiavellian hippie figure is, as always, the exception. And I believe, too, that the paradox may well be that the more like our fellow-citizen we are the less we are likely to suffer in the long run. Shakespeare was unexceptional except in being Shakespeare ..... and that is the greatest argument in favour of being ordinary that I can think of, at the moment. VATE Inside Stories Sometimes Gladness 20 Appendix 3. Teacher Record and Reflection Sheets Teachers find it useful to keep files on texts that might be used from one year to the next. These sheets are intended to cut down the work and make use of the way in which teachers reflect on their practice Sometimes Gladness Poems taught (Title, strategies used, successful features, difficulties for students. Use again- yes/no?) References used (Title, source/ catalogue number) Faculty views about the text in the classroom VATE Inside Stories Sometimes Gladness 21 Teacher Record and Reflection Sheet (cont) Sometimes Gladness Themes (Themes and poems used) Successful discussion topics Tasks set ORAL: WRITTEN Essay topics Handouts for students Changes for next year VATE Inside Stories Sometimes Gladness 22