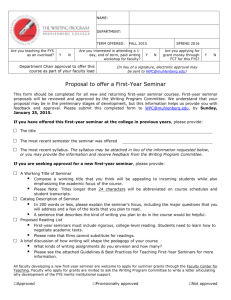

TESTING-GRADING

advertisement