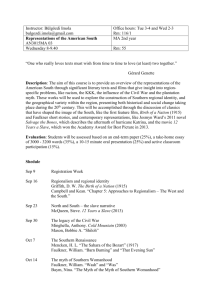

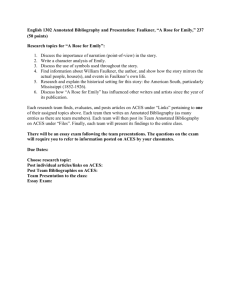

A Good Man Is Hard to Find | Author Biography

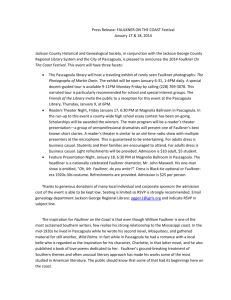

advertisement