Chapter 5: Germans and Greeks

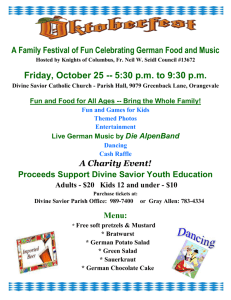

advertisement