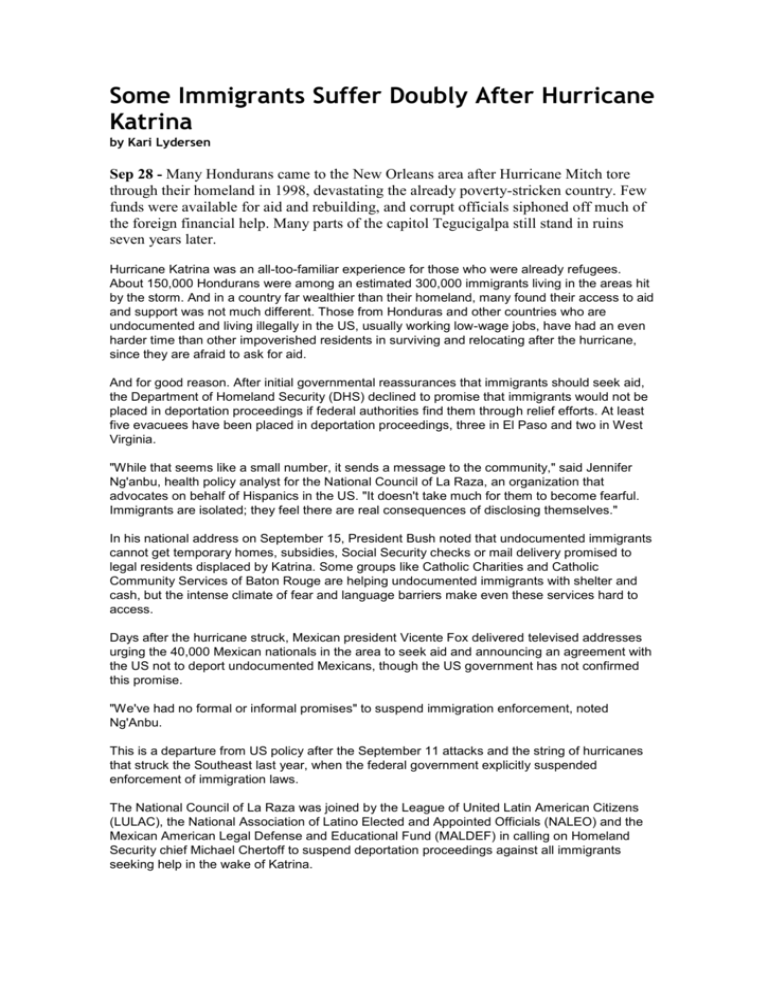

Some Immigrants Suffer Doubly After Hurricane Katrina

advertisement

Some Immigrants Suffer Doubly After Hurricane Katrina by Kari Lydersen Sep 28 - Many Hondurans came to the New Orleans area after Hurricane Mitch tore through their homeland in 1998, devastating the already poverty-stricken country. Few funds were available for aid and rebuilding, and corrupt officials siphoned off much of the foreign financial help. Many parts of the capitol Tegucigalpa still stand in ruins seven years later. Hurricane Katrina was an all-too-familiar experience for those who were already refugees. About 150,000 Hondurans were among an estimated 300,000 immigrants living in the areas hit by the storm. And in a country far wealthier than their homeland, many found their access to aid and support was not much different. Those from Honduras and other countries who are undocumented and living illegally in the US, usually working low-wage jobs, have had an even harder time than other impoverished residents in surviving and relocating after the hurricane, since they are afraid to ask for aid. And for good reason. After initial governmental reassurances that immigrants should seek aid, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) declined to promise that immigrants would not be placed in deportation proceedings if federal authorities find them through relief efforts. At least five evacuees have been placed in deportation proceedings, three in El Paso and two in West Virginia. "While that seems like a small number, it sends a message to the community," said Jennifer Ng'anbu, health policy analyst for the National Council of La Raza, an organization that advocates on behalf of Hispanics in the US. "It doesn't take much for them to become fearful. Immigrants are isolated; they feel there are real consequences of disclosing themselves." In his national address on September 15, President Bush noted that undocumented immigrants cannot get temporary homes, subsidies, Social Security checks or mail delivery promised to legal residents displaced by Katrina. Some groups like Catholic Charities and Catholic Community Services of Baton Rouge are helping undocumented immigrants with shelter and cash, but the intense climate of fear and language barriers make even these services hard to access. Days after the hurricane struck, Mexican president Vicente Fox delivered televised addresses urging the 40,000 Mexican nationals in the area to seek aid and announcing an agreement with the US not to deport undocumented Mexicans, though the US government has not confirmed this promise. "We've had no formal or informal promises" to suspend immigration enforcement, noted Ng'Anbu. This is a departure from US policy after the September 11 attacks and the string of hurricanes that struck the Southeast last year, when the federal government explicitly suspended enforcement of immigration laws. The National Council of La Raza was joined by the League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC), the National Association of Latino Elected and Appointed Officials (NALEO) and the Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational Fund (MALDEF) in calling on Homeland Security chief Michael Chertoff to suspend deportation proceedings against all immigrants seeking help in the wake of Katrina. "Whether folks are undocumented or not, the message that FEMA and the Department of Homeland Security is sending is really mixed, first telling them to report for relief services and then reporting them [to authorities]," said Ng'anbu. "They're frightened, they're not seeking the help they need to get back on their feet." Hondurans and other Central American immigrants made up the bulk of the service sector working in casinos and restaurants in the New Orleans area, while Mexicans and other Latin American immigrants also constituted a large agricultural workforce in the surrounding region. The immigrant population in areas affected by Katrina included the 150,000 Hondurans and 40,000 Mexicans along with about 9,600 Salvadorans, 10,000 Brazilians, and immigrants from Peru, Venezuela, Chile, Panama, Trinidad and Tobago, and Costa Rica, according to numbers provided to the press by consulates. Natalia Fernandez, a Honduran immigrant in the Bronx whose niece and her three children were displaced by Katrina, was close to tears as she described what her family has been through. "There's so much sadness, so many problems," she said in Spanish, describing how her niece and young children were living on the fifth floor of a hotel with no amenities and no elevator and had to walk miles through the heat. They eventually made it to New York to stay with family. "She's so tired, it was so hot, no social workers visited them, no therapy, the kids have been out of school, they had nowhere to go," said Fernandez. "It's a trauma, not only for them but for the whole family. The relatives suffer, too. This is what happens to them for being undocumented." She blamed President Bush for her family's misery. "He's bad; he's a criminal," she said. "People are getting sick emotionally and physically, and he doesn't have a heart. We never had a good government [in Honduras] and we thought it would be different here, but it's the same." Mirtha Colon, with the group Hondurans Against AIDS in New York, noted that since most immigrants from Latin America send money back to their families in home countries, the hurricane will have ripple economic effects across the hemisphere. The fear of detection makes it difficult for consulates and family members to find out what has happened to immigrants. Many do not know if their relatives are safe and where they are. Consulates have generally reported locating only a few hundred of the thousands of their nationals in the region, according to numerous media reports. LULAC has organized the distribution of long-distance phone cards to immigrants in refugee shelters as part of relief efforts that also include sending out roving medical teams and collecting funds for families who have taken in displaced immigrants. LULAC director of policy and legislation Gabriela Lemus noted that several thousand migrant farm workers in particular have been ignored leading up to and throughout the disaster. "They didn't find out about it until it was too late to evacuate, so they didn't have a chance to get out," she said. "They had to batten down the hatches and wait. The farm owners were more concerned about their crops than [about] the workers." Groups including the National Alliance of Latin American and Caribbean Communities and Familias Unidas have urged lawmakers to hasten passing liberal immigration reform bills like the McCain-Kennedy Secure America and Orderly Immigration Act to help undocumented immigrants caught in Katrina avoid deportation and start new lives in the US. Ironically, even as they risk being put into deportation proceedings if they access aid, immigrants are apparently being courted as a major part of government-driven rebuilding New Orleans. In a September 8 Executive Order, President Bush suspended the Davis-Bacon Act requiring construction workers on federal contracts be paid the average wage in a region, and the Department of Homeland Security promised employers it will suspend checking documentation of workers. As advocates see it, this is a microcosm of how immigrant laborers have been treated in the US in general - welcomed and used for their labor, but largely denied job stability, permanent residence and social services.