Scientific Communication (Student Activities)

advertisement

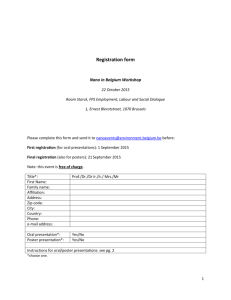

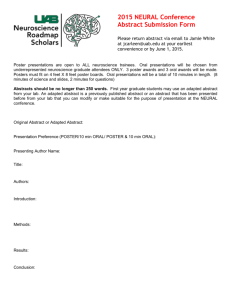

NATIONAL QUALIFICATIONS CURRICULUM SUPPORT Biology Scientific Communication Student Activities [HIGHER] The Scottish Qualifications Authority regularly reviews the arrangements for National Qualifications. Users of all NQ support materials, whether published by Learning and Teaching Scotland or others, are reminded that it is their responsibility to check that the support materials correspond to the requirements of the current arrangements. Acknowledgement Learning and Teaching Scotland gratefully acknowledges this contribution to the National Qualifications support programme for Biology. The publisher gratefully acknowledges permission to use the following source: Text Place memory in Crickets by Jan Wessnitzer, Michal Mangan, Barbara Webb, p. 9915-921, 2008 http://rspb.royalsocietypublishing.org/content/275/1637/915.full.pdf © Text Place memory in Crickets by Jan Wessnitzer, Michal Mangan, Barbara Webb, p. 9915-921, 2008. The Royal Society Every effort has been made to trace all the copyright holders but if any have been inadvertently overlooked, the publishers will be pleased to make the necessary arrangements at the first opportunity. © Learning and Teaching Scotland 2011 This resource may be reproduced in whole or in part for educational purposes by educational establishments in Scotland provided that no profit accrues at any stage. 2 SCIENTIFIC COMMUNICATION (H, BIOLOGY) © Learning and Teaching Scotland 2011 Contents Overview 4 Introduction 4 Activity 1: The scientific research paper 6 Activity 2: The scientific poster 9 Activity 3: The oral presentation 10 Activity 4: Data sharing and the web 14 Activity 5: Summary section 18 SCIENTIFIC COMMUNICATION (H, BIOLOGY) © Learning and Teaching Scotland 2011 3 STUDENT ACTIVITIES Student activities Overview The aims of this unit are: to introduce students to the various methods that scientists use to communicate their work (the scientific paper, poster, presentation) to show students how to prepare their own scientific communication as a poster to show students that the web is a hugely valuable tool for scientists as a resource and a means of communication to show students how science is further communicated via journalists. Included materials: two research paper examples annotated page one of the cricket paper further explanation of Figure 2 in the cricket paper an example poster. Introduction Being able to communicate scientific findings clearly and correctly is a primary skill for a scientist. Accuracy, attention to detail and clearly written observations and descriptions are essential. You may have to present your work to a variety of different audiences so it is important that you are able to convey the message in a suitable format each time. For scientists the main way of communicating their work is via papers published in periodical publications called scientific journals. The journal system dates back to the 17th century, forming to meet a need for scientists or philosophers to publish and share their work. Thousands of these journals exist today, ranging from highly specialist publications (eg Journal of Motor Behaviour) to more general ones such as Nature, Science, Cell, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences and Public Library of Science which publish scientific research across a range of fields. The majority of these publications now also publish their contents on the internet and some (such as 4 SCIENTIFIC COMMUNICATION (H, BIOLOGY) © Learning and Teaching Scotland 2011 STUDENT ACTIVITIES the Public Library of Science journals) are freely available for anyone to download. In addition to journal papers, scientists communicate their work in a number of other ways. These include regular oral or poster presentations to their laboratory and department, and often to their colleagues on the international stage at conferences. Conferences are organised according to field or subject and can have as few as 30 attendees or as many as 30,000 (Society for Neuroscience, Chicago 2009). Early on in their careers scientists will often have communicated their work by writing an academic thesis (ie a BSc, MSc or PhD thesis), which then may lead to a journal publication. These methods of communication are how scientists share their work with each other. It is equally important that they share their findings with the public, the press, the government and educational institutions. Companies, research institutes and universities often have marketing and communication departments who are responsible for informing the press about recent developments or new publications. Many scientists also work full time as science communicators, informing the public via society publi cations, blogs, websites, news articles, podcasts and social media. The advent of the internet has revolutionised scientific communication and data sharing. We now have a large volume of scientific information at our fingertips and an easy way to distribute information. Websites such as YouTube allow experiments to be captured and viewed all over the world, databases such as GenBank hold vast amounts of biological information that can be uploaded and accessed by anyone. The scientific journal paper is stil l the most recognised form of communicating a scientist’s work but online databases are now a vital tool. This unit aims to introduce the various forms of communication used by scientists to report their work. It uses a scientific journal paper as an example of how this is done. You are not expected to understand the intricate details of the paper, but only how quantitative and qualitative information is presented and the logical structure in which the paper is written. SCIENTIFIC COMMUNICATION (H, BIOLOGY) © Learning and Teaching Scotland 2011 5 STUDENT ACTIVITIES Activity 1: The scientific research paper Activity 1a: The structure of a scientific research paper The aim of a scientific paper is to clearly and concisely inform the reader of a piece of original research and present it such that the experiments can easily be repeated by someone else. In order to maintain the standards of the scientific community, research papers are usually set out in a standard format. Title. Author(s): List of all authors who contributed to the paper . Abstract: A short summary of the main aim/hypothesis, results a nd conclusion of the paper. Introduction: An overview of other work in the field and aim of the study . Materials and Methods: Resources required and how the experiments were conducted. Results: Detailed description of observations , usually with figures, and results. Discussion: Reasoned discussion of results with reference to the existing scientific papers and future work. References: Bibliography of other papers mentioned in the text (citations). This standard format makes it easier for scientists to read and understand papers. (In some journals the materials and methods section is placed after the discussion; both formats are demonstrated by examples here.) This structured way of presenting scientific research is common to all means of communicating scientific research, whether it be a research paper, an oral presentation or a poster for a conference. To demonstrate this structure two sample papers are provided. It is not necessary to fully understand the papers, but try to pick out the main aims and results and see how the paper is set out: 1. 2. Wessnitzer J, Mangan M, Webb B (2008) Place memory in crickets. Proceedings of the Royal Society B 275, 915–921. Penn JKM, Zito MF, Kravitz EA (2010) A single social defeat reduces aggression in a highly aggressive strain of Drosophila. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 107(28), 12682–12686. PDF versions of both papers are available for free online. They can easily be found using paper repositories such as Google scholar (http://scholar.google.co.uk/) or PubMed (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/PubMed). 6 SCIENTIFIC COMMUNICATION (H, BIOLOGY) © Learning and Teaching Scotland 2011 STUDENT ACTIVITIES Take a look at the first paper, ‘Place memory in crickets’, and the accompanying annotated version of the front pa ge. The paper is logically set out in the format mentioned above. At the top of the page are the details about the journal that is publishing the paper, the issue, the date and the DOI (digital object identifier), which is a unique identifier for this particular paper. This is then followed by a relevant title for the paper and a list of all authors who contributed to the work. The abstract is a concise description of the background, aim, method and results of the paper. Beneath the abstract are a set of keywords that best fit the content of the paper. These allow the scientist to read a summary of the work and decide if it is relevant or sufficiently interesting to him/her to read further. Activity 1. 2. Write three additional keywords that could be inclu ded in the list for the cricket paper. Write a 150 word abstract on a recent laboratory project you have done in the same style as the one in the sample paper. Include a relevant title and set of keywords. Activity 1b: Presenting results The results section should give a clear, detailed description of the author’s observations and present the results as figures. A figure can contain graphs, diagrams, photographs or images (ie microscopy images of tissue samples) and should summarise the data in the paper. Each figure is always accompanied by a figure legend, which is a short section of text explaining what you are looking at in the figure. The legend often contains details of statistical tests, the number of samples used (e g n = 12) and any abbreviations used in the figure. Figures are one of the most important parts of a paper and useful if you need to ‘skim read’ a paper; you can focus on the abstract and the figures first. Take a look at the figures in the cricket paper. These figures neatly summarise the paper. Figure 1: Explains the apparatus (arena) used and is split into three parts : (a) (b) Shows a cut-away side view and an aerial view of the arena that the cricket will be placed into. Further explains the setup in diagrams, showing the position of t he cool spot and demonstrating how the arena wall moves. SCIENTIFIC COMMUNICATION (H, BIOLOGY) © Learning and Teaching Scotland 2011 7 STUDENT ACTIVITIES (c) A photograph showing the wallpaper on the inside of the arena . Figures 2–4: Graphs and drawings showing the results from subsequent experiments. Look at Figure 2. The three graphs at the top of th e page (a) show the time taken for crickets to find the cool spot. Each graph represents a different visual cue (indicator) situation given to the cricket to assist it in finding the cool spot. This type of graph is called a boxplot and it is explained fu rther in the supplementary materials to this unit. Boxplots are a popular way to display data because they summarise the spread of the data accurately. The data in the first three graphs in Figure 2(a) ha ve been summarised as one graph below in Figure 2(b) using the mean value for each boxplot. In this line graph, each line represents the mean time to locate the cool spot for each group of crickets per trial. The three lines represent the three visual conditions (i, ii, iii) and therefore three different g raphs. Several other types of graphical presentation formats can be used to present data, eg bar charts, histograms, pie charts, scatter plots and many others. Which one you use is often up to you as long as it displays the data accurately and is straightforward to interpret. The final section of a paper is the discussion section. This is where the authors explain their results and propose conclusions based on the evidence from the results. In addition, the authors discuss not only their own work but how it relates to other research papers in the field. This is also an opportunity to propose ideas for future work. The discussion section is followed by a reference list detailing all of the research papers cited in this paper. The citation of other work in the field is a critical part of scientific writing, not only so readers can follow up related work but as a means of crediting the work of other scientists. Before a scientist embarks on a new study they first read the relevant literature (papers) in the area so that they are as fully informed as possible. This background reading will shape the study, reveal tried and tested methods, advise on resources and spark new ideas. It also prevents someone doing the same study twice (although this still happens sometimes so two groups will publish a similar study at the same time). In summary, scientific papers are the primary method for distributing scientific research and informing the world of new advances. 8 SCIENTIFIC COMMUNICATION (H, BIOLOGY) © Learning and Teaching Scotland 2011 STUDENT ACTIVITIES Activity 1. 2. What is the purpose of a figure in the r esults section? Draw a graph showing a set of data from a recent lab oratory experiment you have done or from a textbook. Try to use the same data that you wrote the abstract for in Activity 1a. You can either draw the graph or use a computer. Activity 2: The scientific poster Poster presentations are quite common in the sciences as a way of communicating work prior to publication. They are usually used to display unpublished work at a conference or a university department event. Some large conferences attract thousands of posters so it is important that a poster is designed to stand out and be noticed. Usually the author stands beside their poster to answer any questions, explain their results further and discuss their work. A poster should be: visually attractive (use colour, diagrams, graphs) concise and informative spilt up into sections (abstract, introduction, methods, results, conclusions) clearly labelled with the author’s name, email address and place of study . Activity 1. Design your own poster for a recent laboratory project/practical using the abstract and figures you made in Activity 1a and b. The poster should include: a title your name your school logo (optional) an abstract introduction methods – a diagram describing the method(s) used results – containing graphs conclusion(s). An example poster layout is provided, but you can design your poster any way you like. SCIENTIFIC COMMUNICATION (H, BIOLOGY) © Learning and Teaching Scotland 2011 9 STUDENT ACTIVITIES Further reading Ten Simple Rules for a Good Poster Presentation , Thomas C. Erren and Philip E. Bourne: http://www.ploscompbiol.org/article/info%3Adoi%2F10.1371%2Fjournal.pcb i.0030102. This article is open access, ie available to anyone with connection to the internet. Activity 3: The oral presentation Oral presentations form a big part of science communication, but delivering a good talk – whether it is to an audience of five or one of five hundred – takes practice. This section will get students thinking about what makes an effective presentation and offers students some advice and tips for preparing their own talks. Activity 3a: Comparing different presentation scenarios in science Scientists encounter a range of situations where they might be required to give a presentation so it is important to think about what factors should be considered when preparing a talk in different situations. Activity For the three scenarios below consider how presentation content and style might differ. What is the purpose of each presentati on? Also think about the target audience. What is motivating them to attend? What background knowledge do they have and what are their expectations? 1. University lecture The majority of teaching at university is done in the form of lectures, with the lecturer standing at the front of the lecture theatre presenting information students need to help understand a particular topic they are studying. 2. Public engagement talk University lecturers are often asked to communicate exciting ideas in science to the general public. They might talk about their own research or highlight a particular topic that is currently receiving a lot of attention. 10 SCIENTIFIC COMMUNICATION (H, BIOLOGY) © Learning and Teaching Scotland 2011 STUDENT ACTIVITIES 3. Conference seminar Conferences provide scientists with an opportunity to present and discuss their work with colleagues from all over the world, and speakers invited to talk usually present recent findings from their own laboratory. Target audience Purpose Audience background and motivation Style and content of talk University lecture Public engagement talk Conference seminar SCIENTIFIC COMMUNICATION (H, BIOLOGY) © Learning and Teaching Scotland 2011 11 STUDENT ACTIVITIES Activity 3b: How to prepare an effective presentation There a many situations where giving a talk can be useful, and not just in science. The more experience you have of giving presentations the easier and more enjoyable they become. Planning Research your topic and prepare an outline. Organise your material and establish a logical structure. Think about time and don’t try and cover too much material. Select the best structure for the topic and the audience, eg presenting a laboratory report to your classmates might be broken down into introduction, methods, results and conclusion. Think about your key points, and if necessary use examples to illustrate what you are trying to get across. Preparation An introduction should include an outline to your talk and some relevant background covering the topic. The main content of the presentation should be concise and focused, and follow the outline. Provide your audience with a clear summary and make it obvious when you have reached the end of your presentation. Emphasise the main points before providing an opportunity for questions. Visual cues can make a talk more interesting and understandable. Microsoft PowerPoint can be used to produce support slides for your talk (see below). I t can also be useful to prepare a handout for your presentations to reinforce your key ideas. A reference list and suggested further reading are helpful too. Practise your talk. Go through it a few times, trying to recreate the speaking situation and time yourself. Presentation When delivering your presentation look around the room, make eye contact and smile. Speak clearly and loudly enough for everyone in the room to hear you. Use notes or cue cards, but don’t read directly from them – speak to the audience. If you’re using PowerPoint to support your talk avoid blocking the view. Look at the audience and not back at the screen. At the end of your talk there may be an opportunity for the audience to ask questions. Listen carefully to the question an d keep your answer simple and 12 SCIENTIFIC COMMUNICATION (H, BIOLOGY) © Learning and Teaching Scotland 2011 STUDENT ACTIVITIES short. Questions are a good thing – they show your audience are interested and listening, and can provide good points for further discussion. Using PowerPoint for presentations Microsoft PowerPoint has long been the standard software for creating visual support for presentations. It provides anyone with the need to present information creatively and professionally with the ability to develop presentations quickly, easily and effectively. Top tips for producing slides: Use a clear, easy-to-read typeface and keep words to a minimum, with only a few points on each slide. Aim for a slide every 1–2 minutes, so a 10-minute talk should have no more than 10 slides, including introduction and summary slides. Give the audience time to take notes form the slides, but don’t cram the slides full of facts. They should be listening to you, not reading the slide. Use colour, pictures and graphs to make slides more interesting – sometimes it is easier to remember a picture rather than words describing a particular fact or idea. Don’t spend more time producing slides full of fancy graphics than on the talk itself. A simple set of slides and a well -thought-out talk is always best. Top five tips for effective presentations 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Be prepared – know your talk inside out. Be organised before you begin – order your notes, sort handouts, check computer/projector. Don’t rush through just to get it over with quickly. Slow down and make use of natural pauses (eg at the end of a point or changing slides) to take a breath or a sip of water. Stick to the suggested time limit – people lose interest and stop paying attention when talks run over time. Finally, a bit of nervousness is good – adrenalin helps you to focus and perform well, just don’t let it take over from the presentation. SCIENTIFIC COMMUNICATION (H, BIOLOGY) © Learning and Teaching Scotland 2011 13 STUDENT ACTIVITIES Activity 1. 2. What are the advantages and disadvantage of using Microsoft PowerPoint for presentations? Discuss your ideas in small groups. Prepare your own 5–10-minute presentation. Further reading Ten Simple Rules for Making Good Oral Presentations, Philip E Bourne: http://www.ploscompbiol.org/article/info%3Adoi%2F10.1371%2Fjournal.pcb i.0030077. Activity 4: Science, data sharing and the web The revolution of the internet Although the internet was officially invented in the 1960s by the Arpanet project in the USA, it didn’t reach the public until in the 1990s. The advent of the internet has facilitated access to scientific data, papers, lectures and other scientists, and it is now the first place most of us turn to for information. This is mainly advantageous but it is important to be aware of the source of the information, especially in science as it is often misreported or misi nterpreted. As we saw earlier, one of the most valuable sources o f information are scientific papers. Prior to the internet papers were accessed via journal subscriptions and using libraries such as the British Library or university libraries. Copies of papers would be painstakingly photocopied or read on site. Today, large databases such as PubMed (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed) and Google scholar (http://scholar.google.co.uk/) exist that allow us to type in a subject, title or author name and return a list of all relevant scientific journal publications with links to the paper via the journal’s website. This allows the scientist to find and download an electronic copy of the paper within seconds, saving them the trip to the library. The internet is revolutionising scientific publishing, with new open-access publishing (no subscription fee so downloading an article is free), meaning that anyone in the world with an internet connection can access the latest scientific findings for themselves. The internet has also reduced the time taken for a research paper to be published. Although the conventional print publishing model still exists, papers are now also published online immediately after they are accepted by the journal, thereby allowing scientists to get their work out faster. The use of social media such as Twitter, Facebook, FriendFeed and LinkedIn give scientists a platform to promote their work to intereste d parties and allows 14 SCIENTIFIC COMMUNICATION (H, BIOLOGY) © Learning and Teaching Scotland 2011 STUDENT ACTIVITIES them to receive direct feedback on the paper. In addition several scientists now write highly regarded blogs. Scientists have access to a range of official databases , such as GenBank (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/), where they can upload genetic sequences as soon as they are known. This allows scientists to share their data immediately with others all over the world and acts a large storage area for biological information. There are now several databases specialising in a variety of areas in the sciences that are used daily all over the world. Considering new media as a tool for communicating science Public awareness and understanding of science is important, and research scientists are often encouraged to promote or communicate their work to wider audiences. The internet is an essential resource for communicating science. Over recent years new technologies have developed innovative applications that are quickly becoming important in the communication of science. Collectively known as ‘new media’, sites such as YouTube, Facebook and Twitter are changing the way scientists communicate with each other and the general public. SCIENTIFIC COMMUNICATION (H, BIOLOGY) © Learning and Teaching Scotland 2011 15 STUDENT ACTIVITIES Activity 4a: Defining new media in the context of science communication We all know and recognise Facebook as a personal social network, but it can also be used as a communication tool in science. Consider the University of Edinburgh’s Facebook page below as an example. 16 SCIENTIFIC COMMUNICATION (H, BIOLOGY) © Learning and Teaching Scotland 2011 STUDENT ACTIVITIES Activity 1. How would you describe the University of Edinburgh’s Neuroscience Department Facebook page? In small groups, produce a list of key words explaining its purpose and how it might be useful. 2. What are the advantages and disadvantages of using new media, such a s Facebook, to communicate science? Activity 4b: Tweeting a piece of science Read the following abstract modified from a real scientific research paper and have a go at writing an accompanying tweet. This is harder than it sounds. You only have 140 cha racters to get your message across, which means your tweet has be concise and compelling – difficult in science. ‘The contribution of genetics and the environment to fighting behaviour in Drosophila is unclear. To address this issue we bred hyper -aggressive flies by selecting winners of fights over several generations. Males of this hyper aggressive strain initiate fights sooner, retaliate more often and regularly defeat opponents from a non-selected strain. However, if an aggressive fly experiences a defeat against a fellow aggressive it looses its competitive edge against a non-selected opponent in a following fight. These flies, once capable of engaging in high intensity patterns of aggressive behaviour, showed reduced lunging and retaliation, suggesting that a single loss is enough to lower aggression in flies bred to be hyper -aggressive. Furthermore, females were more likely to copulate with males from the non -selected strain than with hyper-aggressive flies.’ Abstract modified from the scientific paper: A single social defeat reduces aggression in a highly aggressive strain of Drosophila. Penn et al. (2010) Proceedings of the National Academy of Science 107, 28. Useful links http://schaechter.asmblog.org/ A retired scientist turned blogger. http://scitalks.com/index.php A website hosting a range of videos covering many scientific fields . SCIENTIFIC COMMUNICATION (H, BIOLOGY) © Learning and Teaching Scotland 2011 17 STUDENT ACTIVITIES http://www.jpl.nasa.gov/social/ NASA uses a variety of Facebook and Twitter groups to inform the public about its missions. Activity 5: Summary section 1. Make a table of the common sections that can be found in these three different scientific communication formats: a research paper, a poster and a presentation. Compare the three formats and include a section detailing the advantages and disadvantages of each (eg time, detail, references). 2. In a group, imagine that you have just published a paper on the same topic as the poster that you designed earlier. Make a list outlining a strategy that you would use to publicise this paper. Would you use social media, make a video, local/national newspapers, a personal website/blog, a conference? 3. Name two officially recognised sources of s cientific information and two unofficial ones. For each discuss who the audience for the information could be. 18 SCIENTIFIC COMMUNICATION (H, BIOLOGY) © Learning and Teaching Scotland 2011