Liveability urban architectures PUBLICATION

advertisement

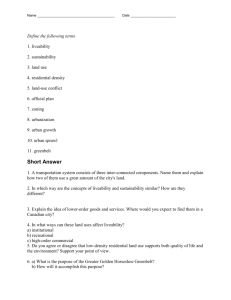

Liveability and urban architectures: Mol(ecul)ar biopower and the becoming-lively of Sustainable Communities Abstract Contemporary analyses of biopolitics and the governance of ‘life-itself’ have concentrated on molecular processes in domains such as medicine and neuroscience. In this paper, I turn an analytical lens on urban architectures, with a focus upon a particular programme of largescale house-building in the UK: the Sustainable Communities agenda. I argue first that Sustainable Communities constitute a resonant but qualitatively different attempt to plan for and govern life-itself, particularly encapsulated by the term ‘liveability’. Significantly, according to policy and technical documentation, Sustainable Communities appear to address the future at both molar and molecular levels, and through a focus on obduracy in ordinary, banal, everyday spaces (rather than in exceptional or border architectures). My analysis is, however, interwoven with attention to the ‘becoming-lively’ of urban architectures. Drawing on a large, ethnographic research project, the paper offers three navigational aids to understanding how professionalised deployments of ‘liveability’ become co-opted into, resisted by, or creatively reinterpreted through, practices of inhabitation by residents of Sustainable Communities. Keywords Sustainable urbanism; urban planning; urban geography; geographies of architecture; dissonance; childhood and youth; children’s geographies I Introduction Ever since Michel Foucault’s critical interrogation of biopower, there has been gathering interest in the exercise of surveillance, control and design over “life itself” (Foucault, 1978, page 143). Countless studies have considered the implications of the confluence of life, politics and finance in: from genetic manipulation to neuroscience, and from pharmacology to the “customised fabrication of DNA sequences” (Rose, 2007, page 13). Compelled by a desire to both control and allow for (carefully selected) contingencies, there is growing agreement that neoliberal modes of governmentality are underpinned by increased intervention against possible threats to kinds of life that are deemed ‘normal’ (Anderson, 2010). A foundational concept in studies of life-itself has been a shift from intervention at the ‘molar’ to the ‘molecular’ scale, articulated in Nikolas Rose’s (2007) seminal analysis of contemporary biomedical knowledges. For Rose, the molar constitutes the scale of individual (human) bodies and their perceptible components: “limbs, organs, tissues, flows of blood, hormones” (Rose, 2007, page 11). Rose highlights how, until the later-twentieth century, this “molar body” (Rose, 2007, page 11) was visualised and acted upon by an earlier logic of medical intervention, supporting “the state [...] in measures for preserving and managing the collective health of the population” (Rose, 2007, page 24). Rose contrasts such molar knowledges with the rise of a molecular scopic, increasing in intensity from the late-twentieth century onwards. Whilst Rose (2007, page 33) recognises the “need to be cautious about overstating the novelty of these developments”, he nonetheless locates a shift to the molecular scale of genes, DNA, and a range of technologies which visualise such lifecomponents. Thus, the molecular now represents a pervasive “style of thought” (Rose, 2007, page 4) wherein scientific endeavour, policy making, health interventions, and entire commercial industries are entangled. More recently, scholars have shown how the politics of life-itself are inveigled variegated anticipatory and preventative logics: from climate change to terrorism to bio-threats (Anderson, 2012, page 32; also Amoore, 2006; Braun, 2007). These advances notwithstanding, there remain important lacunae in contemporary investigations of the politics of life-itself. The most significant for this paper relates to professional interventions that have gained less attention than biomedicine, terrorism, biosecurity, food, and contingency planning: interventions like architecture, planning and urban design. Perhaps these interventions – henceforth termed ‘urban architectures’ – have not been theorised in biopolitical terms because they seem not to resonate wholly with the tendency to molecular interventions into life-itself. However, it is argued that certain contemporary large-scale housing schemes have became increasingly characterised by practices that hold striking parallels with other contemporary forms of biopower. Like Rose (2007), I urge caution about the novelty of these developments: architects and planners have frequently sought to plan for life-itself, especially in large-scale urban programmes. Yet, neither such previous waves of urban development (such as Garden Cities), nor more contemporary forms, have been subject to biopolitical analyses. Critically, the twenty-firstcentury English example used in this paper is an excellent case study because – although resonating with historical state-led urban programmes – it is one of several contemporary contexts wherein urban-architectural professionals have explicitly sought both to articulate and to intensify a focus on life-itself. The focus of this paper will, therefore, be on new urban places in England planned under a large, UK-Government-sanctioned project of housebuilding: the Sustainable Communities agenda (ODPM, 2003). Sustainable Communities represent an important – but not unique – example of the confluence of urban architectures with politics of life-itself. Principally, this is because of the ways in which urban architectural practitioners combine both molar and molecular processes in the service of a particular version of life: ‘liveability’. The paper also attends to two further concerns. Firstly, it questions what becomes of Sustainable Communities, after formal planning/construction: how ‘liveability’ might become-lively, through everyday lives lived therein. Several scholars have called for attention to the ways in which ‘ordinary’ subjects might negotiate or resist the ‘expert’ exercise of biopower from below (e.g. Anderson, 2012, Braidotti, 2011). Therefore, this paper is based both upon a critical reading of Sustainable Communities policy documentation and empirical vignettes from a large, ethnographic research project that explored the lives of residents in four new communities. The paper inventories three navigational aids to articulate how ‘liveability’ may intersect with residents’ everyday lives – both with specific regard to Sustainable Communities, and as a set of analytical tools for future research into the confluence of urban architectures and politics of life-itself. Secondly, and herein, the paper offers significant implications for geographical theorisations of architecture. Other than important studies of materiality (Jacobs, 2006) and inhabitation (Lees, 2001), no studies seek to directly interrogate how biopolitical processes are constituted through architectural practices. Thus, section II provides a brief, critical introduction to contemporary geographies of architecture, before introducing the research project and case study communities appearing in this paper. Thereafter, section III offers three navigational aids to better conceptualise entanglements of urban-architectural planning/inhabitation. II Geographies of architecture: analysing Sustainable Communities This paper focuses upon the constitution of urban architectures through the English Sustainable Communities agenda. The term ‘urban architectures’ encompasses a range of materialities, technologies, performances and regulatory frameworks through which urban places are planned, built and inhabited. Conceptually and methodologically, there exist important resonances between the analyses in this paper and recent geographies of architecture. First, it seeks to examine how politics and practices of design interact with inhabitation. Similarly, in Lees’ (2001) call for a critical geography of architecture, earlier approaches to the symbolism and/or iconography of buildings were supplemented with ethnographic methods, designed to witness performances through which a range of actors – including inhabitants – made buildings meaningful (also Kraftl, 2006, 2009; den Besten et al., 2008 Jacobs and Merriman, 2011). Second, a range of studies has sought to extend Lees’ analyses through attention to the emotions and affects that are designed and felt at buildings (Rose et al., 2010). For instance, Kraftl and Adey (2008) draw on geographical theorisations of affect to examine how particular kinds of atmospheres – rest, homeliness, peace – are built-into and performed at two buildings. Third, important strides have been made in theorising the materialities of built form (Jenkins, 2002; Jacobs, 2006). Thus, Jacobs et al. (2007) demonstrate how particular building technologies (such as windows) are enrolled into the lifecourse of a building – from conception, through inhabitation, through demolition. Whilst I have reduced geographical scholarship on architecture to a brief, three-fold schema, it is important to note both resonances and dissonances with the approach in this paper. On one hand, the paper draws inspiration from the above studies, clearly drawing out entanglements of design with affective regimes, everyday practices and the particular materialities of stone, water and plant-life. On the other, it deploys these approaches within a novel analytical framework that offers more than another new methodology for studying buildings: namely, an interrogation of biopolitical regimes as these are constituted through architectural design and inhabitation. Specifically, urban architectural practices ‘speak back’ to theorisations of life-itself because of the combination of molar with molecular knowledges. Geographical studies of architecture have represented one inspiration for the research project upon which this paper is based1. The project was a large, four-year, interdisciplinary research effort. It focussed upon four new communities in the Milton Keynes-South Midlands Growth Area, located between London and Birmingham, itself one of four Growth Areas in which the New Labour Government sought to concentrate large-scale house-building after 2000. Given that the Sustainable Communities plan involved commitment to hundreds of thousands of new homes in southern England, it was striking that, when the project began, little was known about experiences of their residents. The project therefore aimed to examine everyday lives, mobilities and senses of citizenship amongst residents living in such communities, but particularly young people aged 9-16. An ethnographic approach was adopted, underpinned by six months of participant observation at each community. Across the four communities, researchers also undertook detailed, directed qualitative research with 175 young people, professional stakeholders, and family groups. In brief, that research comprised: 311 semistructured interviews with young people (each interviewed up to four times); 22 ‘community walks’ (walks directed by young people), 32 semi-structured interviews with professional stakeholders; a ‘GPS’ week, whereby 90 young people carried a GPS device, which recorded their movements, and took part in subsequent interviews about their mobilities; participatory community workshops, involving adult and child residents and a range of policymakers and practitioners (see Kraftl and Horton, 2007, for fuller details). All interviews were digitally recorded, transcribed and collated with observational fieldnotes before thematic analysis in NVivo2. 1 The other principal academic context has been interdisciplinary childhood studies (including Children’s Geographies), whose principles frame but are tangential to the current paper. There is not space to include a full review (see Horton and Kraftl, 2006 for one such review), but relevant sub-disciplinary texts are cited throughout this paper. 2 The ‘New Urbanisms, New Citizens’ project website provides fuller methodological details: see http://newcitizens.wordpress.com; see also Kraftl et al., forthcoming. Given that this paper seeks to offer several “navigational aids” (Lee and Motzkau, 2011, page 8) for interrogating biopolitics in and of Sustainable Communities, it cannot do justice to the large qualitative dataset produced by the project. Thus, the paper proceeds through critical discussion of relevant policy documents, and through a series of indicative quotations and observations from two of the four case study communities. The analysis is led by key biopolitical concerns evident in policy documents, but then follows through how some of these concerns are experienced, enlivened or negotiated by residents. The two communities included in the analysis for this paper have been chosen because, whilst of comparable size, they represent both different incarnations of Sustainable Communities policy, and contrasting expressions of life-as-‘liveability’. The first community – Hettonbury3 – is a so-called ‘sustainable urban extension’, which will comprise approximately 1,000 new homes. It is located on the periphery of a large South Midlands town, on a formerly undeveloped floodplain. It has been vaunted as an exemplar for the Sustainable Communities agenda, precisely because of its meticulous, holistic planning processes and objectives. Hettonbury was built to deal with several future problems: climate change and resource depletion, where “most housing developments fail to deliver high standards of energy efficiency and sustainability” (Energy Saving Trust, 2006, page 2 4); the embedding of sustainable principles “in conventional forms of housing that could meet the expectations of prospective homebuyers” (Energy Saving Trust, 2006, page 2); enormous pressure for housing in the South Midlands; the threat of one-in-a-hundred year flood-events; desire for a mixture of housing tenures (owner-occupied, rental and Local Authoritycontrolled) that would foster social cohesion. Hettonbury is notable for the ‘Enquiry by 3 In order to follow the ethical approval procedures for the research project on which this paper was based, the two communities reported in this paper have been anonymised, using pseudonyms and removing any identifying information. 4 In order to retain anonymity for Hettonbury, the full source for this document has not been included in this article. Design’ (EbD) approach that was used. This led to a complex constellation of stakeholders (local communities, Local Authorities, private developers, planning and design professionals, Housing Associations) being involved in an iterative consultation lasting several years prior to building commencement5. Thereafter, this complexity was transferred into a meticulous, “clear and demanding design code which left potential developers in no doubt of their obligations” (Energy Saving Trust, 2006, page 2). The design code specified tremendous detail about the variety of housing styles, the syntax of public streets/squares, green-spaces, the distance of houses from the street, and much more besides. Also comprising 1,000 new homes, the second community – Romsworth – bears many superficial similarities with Hettonbury. However, it differs in three respects. First, it is a stand-alone settlement, built on former farming land five miles from the nearest town. Second, whilst homes meet minimum UK environmental standards, few feature the environmental technologies at Hettonbury. Third, and most significantly, the history of Romsworth’s planning is quite different. The village site was sold by a local landowner on the premise that a ‘community’ would be built. Thus, when the land was sold to subsequent developers, this imperative had to be incorporated into Romsworth’s layout, green spaces, and facilities. In this last respect, the plan has been successful – unusually for the UK, for what effectively a large village, it houses a surgery and dentist, several shops, a school, a playground, a community centre, and a cafe. In terms of Romsworth’s urban architecture, the effect is less obvious (Plate 1): superficially, it looks like a neo-traditional village. PLATE 1: ROMSWORTH VILLAGE, INCLUDING ‘LOCAL’ HOUSING STYLE AND PUBLIC GREENSPACE (LEFT) 5 For further details, see http://www.princes-foundation.org/content/enquiry-design, last accessed 11th June 2013 Whilst unique in some respects, Hettonbury and Romsworth bear clear similarities with other planned communities, built both in previous historical epochs and other contemporary geographical contexts (from Garden Cities to postmodern urbanism). To repeat: paralleling Rose’s (2007) observation for the medical sciences, there is a long history of attending to concepts such as sociability in urban architectural professions (e.g. Hall and Ward, 1998). Whilst there is not space to rehearse the history of large-scale town-planning, the paper’s conclusion nevertheless stresses some of these resonances. However, the aim of the remainder of the paper is to demonstrate how Sustainable Communities – in their design and inhabitation – offer a particularly important, if not more intense, set of navigational aids for understanding the conflation of urban architecture with contemporary efforts to govern lifeitself. In particular, the following analyses are concerned with the explicit naming of particular forms of life (as ‘liveability’), the dense complexity of contemporary masterplanning processes, and attentiveness to facets of life that have come to characterise contemporary biopolitics in other domains – specifically, molecularised technologies and regimes of affect. III Sustainable Communities and mol(ecul)ar biopolitics The UK New Labour Government of 1997-2010 engaged in several large-scale, purportedly transformative capital projects. Raco (2005, page 333) argues these projects represented “holistic” spatial strategies whereby “local economic, social, political and environmental problems [were] tackled simultaneously”. Thus, as part of a programme for the renaissance of Britain’s urban places (Lees, 2003), the Sustainable Communities Plan sought simultaneously: • “to accommodate the new homes we need by 2021 […]; • to encourage people to remain and move back into urban areas […]; • to tackle the poor quality of life and lack of opportunity in certain urban areas as a matter of social justice […]; • to strengthen the factors in all urban areas which will enhance their economic success […]; • to make sustainable urban living practical, affordable and attractive” (ODPM, 2000, p.37). The earlier Urban Task Force Report (Rogers et al., 1999), which formed an inspiration for the Plan, articulated an early link between such holism and questions of ‘life-itself’: “[a] key message [...] was that urban neighbourhoods should be vital, safe and beautiful places to live. This is not just a matter of aesthetics, but of economics. As cities compete with each other [...] their credentials as attractive, vibrant homes are major selling points. (Rogers, 1999, page 5, emphases added) Encompassing economics, safety, community, social integration, place-making, aesthetics (and far more) it is the holism of this agenda that is key. It articulates – even if it does not necessarily deliver – a “qualitative increase in our capacities to engineer our vitality, our development” (Rose, 2007, page 4), through an attempt to subject all knowable elements of urban life to intervention and capitalisation. This agenda is couched in the language of ‘lifeitself’: of ‘vibrancy’, ‘vitality’ (in the above quotation) and, importantly, as noted in the next section, ‘liveability’. At this general level, the Task Force report can be understood as a fairly typical example of the articulation of life-processes that constitutes both molar and molecular forms biopower. Indeed, the clear economic objectives (and associated emphasis upon private capital or PFI in financing Sustainable Communities) reinforce a sense of what Rose (2007, page 31) calls “the capitalization of vitality”, through the increasingly “path-dependent” nature of professional, governmental and business worlds. Yet most critical commentators would (rightly) point out that these processes seem at most to denote an intensification of the focus upon life-itself, rather than a “step-change” (Rose, 2007, page 4). Nonetheless, whilst Sustainable Communities may appear to offer relatively little novelty in terms of urban planning, there are important resonances and dissonances in what they (and similar programmes) offer to theorisations of life-itself. Clearly, this claim requires more detailed examination of Sustainable Communities and, especially, the concept of ‘liveability’. Therefore, the rest of this section outlines three navigational aids through which the conflation of urban architectures and the politics of life-itself might be understood: resonance; obduracy; dissonance. Resonance: the production and take-up of ‘liveability’ New Labour’s Sustainable Communities Plan (ODPM, 2003) marks an important document because of its articulation of ‘liveability’. The term exists in several other contexts (not least in a series of global liveability indices), yet in the Sustainable Communities Plan and subsequent local incarnations, it represents a particular way of knowing, constructing and governing life – in detail – in Sustainable Communities. The term ‘liveability’ helped specify how life-itself was to be master-planned. Redolent with the holism introduced above, the term applied to several facets of life simultaneously. First, to a tranche of money – £201 million – to be invested in “Local Environment/Liveability” (ODPM, 2003, page 7). Second, it specified how ‘liveability’ was to become a by-word for the materialities of the urban environment that would improve public well-being. Thus, liveability was used interchangeably with “sustainability” to encapsulate ideas from “quality of life” to environmental standards around rubbish, graffiti and housing (ODPM, 2003, page 13). Amongst a long list, socio-environmental quality of life indicators underpinning liveability in Sustainable Communities included: “22 The proportion of developed land that is derelict. 23 The proportion of relevant land [...] assessed as having combined deposits of litter [...] 28 The percentage of river length assessed as (a) good biological quality; and (b) good chemical quality. 29 The volume of household waste collected and the proportion recycled” (taken from 45 ‘Local Quality of Life Indicators’: Audit Commission, 2005). These standards would, in turn, make Sustainable Communities more vibrant places for investment by both homeowners and businesses. Third, liveability could be assured through the creation of so-called “Living Places”: “cleaner, safer and greener” public spaces (ODPM, 2002, page 1). Here (for instance through Hettonbury’s EbD process), the focus was on master-planning parks, urban gardens and public squares to strict design and management criteria, which would be integrated into the urban architectures of new communities (ODPM, 2003, pages 19-20). The paper returns to this particular issue in its later discussion of obduracy. Fourth, New Labour’s policy on public spaces involved measures to secure “Living Places”. A further £50 million of the Sustainable Communities Plan was committed to “Neighbourhood Warden Schemes”. An exemplar scheme cited by ODPM sought to employ local residents as wardens in order to: “overcome environmental factors contributing to crime; divert young people from involvement in crime and disorder; protect and support victims; reduce burglaries [...]; increase community ownership; and have a sustainable crime and disorder strategy” (cited in ODPM, 2002, page 30) The securitisation of public spaces was to be supported by top-down measures for the management of public spaces via Comprehensive Performance Assessment: “Comprehensive Performance Assessment will be developed further to embrace liveability issues. From April 2003, local authorities will measure local environmental quality, in respect of litter and rubbish, through a new ‘cleanliness BV Performance Indicator’” (ODPM, 2003, page 20, emphasis added). Through the minutiae of design, liveability indicators, securitisation and performance assessment, ‘liveability’ represents a specific style of thought about life-itself whose intensity is characterised by both detail and holism. It is but one example of “a complex geography where states and locales [...] are increasingly asked to conform to what is regarded (in the metropolitan core) as a safe world” (Bingham et al., 2008, page 1529). But, whilst premised upon the over-riding imperative to secure particular kinds of life through embodied regulatory techniques (Amoore, 2006), Sustainable Communities also differed in important ways. This is principally because “often it is microbes”, synapses, genes and other molecularscaled elements that hold the ultimate currency for biopolitical power (Bingham et al., 2008, page 1528; also Nally, 2011). In distinction, as evidenced above, intervention in Sustainable Communities was also planned at the molar level: of communities, of interaction between human bodies, of ‘public health’, of visible, material, urban environments. Thus, I accord with some isolated studies that have begun to critique apparent overemphasis upon molecuarlised biopower (Wahlberg, 2009). For instance, in their study of Danish neoliberal public health policies, Frandsen and Triantafillou (2011) observe that those policies still use the ‘population’ or ‘society’ as key benchmarks. Thus, interventions are not solely geared to changing behaviours through molecularised knowledges, but to support for ‘healthy’ lifestyles at several scales: through “supportive institutional settings such as workplaces, schools, local housing neighbourhoods and families for making the ‘free’ and healthy choice” (Frandsen and Triantafillou, 2011, page 214). The distinction is not that lifeitself (as ‘liveability’) occurs a priori at the molar scale, thence to be governed. Rather, it is that the multiple governmental practices that compose liveability also constitute the molar as a scale at which intervention into life-itself is possible. This important observation notwithstanding, the molecular scale remains evident in liveability planning. In the service of liveability (and related terms, such as conviviality and cohesion), the above guidance specified in detail how Sustainable Communities might become liveable in terms of their social lives. Thus, terms like ‘conviviality’ referred to the governance of sociabilities within communities: to the manipulation of the social life of urbanities towards some kind of (ideally long-lasting, sustainable, but often vaguely-defined) affective ‘good’ (Thrift, 2004), such as social inclusion. Such an attention upon affect acts as a reminder that liveability operates not only at the molar scale, but the molecular scale too: it is mol(ecul)ar. To evidence this claim, it is instructive to turn to one of the two case studies: Romsworth. As noted in section II, liveability was introduced at Romsworth through an initially illdefined but ultimately powerful process of naming the new development a ‘community’, before letting life take its course. Through the simple deployment of the term at an apposite stage of Romsworth’s construction, ‘community’ has become a discursive-affective concept that has engaged residents in a series of coded practices that have led towards a particular sense of conviviality (cf Valentine, 2008). In interviews with longer-term residents, several examples emerged. Firstly, many early residents moved to Romsworth both because it was advertised as a living community (not ‘just’ a new housing development) and because they wanted to take part in building a new community. Secondly, the first residents developed a shared sense of pioneer spirit. They spoke nostalgically of being the first families to move in, when only a few homes were completed; of how every new family was welcomed personally by an existing resident, and given a bottle of wine; of the common struggles entailed in living on a building site; and so on. Thirdly, Romsworth is notable for the sheer variety of locallyorganised activities through which ‘community’ is constituted. There is an endless list of community-badged events (fetes, fireworks, etcetera), resources (an online village forum and newsletter), social groups (a youth group, scouts, guides, sports teams) and political representation (a highly active Parish Council). In itself this list is not remarkable, although it represents a small selection: perhaps more remarkable is the speed and vigour with which these groups have been organised. It is not unusual for new settlements in the UK to be built with a proviso for community planning6. Romsworth is, though, notable because of how the notion of community has been 6 For instance, Section 106 agreements contractually oblige developers into the creation of some kind of community facilities when they invest in large housing schemes. taken-up particularly enthusiastically – and given life – by its residents. As evidenced in the next section it emerged that – as a result of this take-up – everybody just knows that community matters in Romsworth, and, moreover, that community means something quite particular there. For now, though, it is worth noting that community is something that is talked about, practiced and felt (as affect). Thus, the affectivities of community at Romsworth lead to some specific reflections upon “the claim […] that biopower now targets and works through affect understood as molecular bodily charges that are pre- or non-conscious (Anderson, 2012, page 30). For most commentators, these modes of intervention rely on the “somatic expertise” (Rose, 2007, page 6) of professionals, which in turn enable the circulation of discursive-affective codes that pattern the interaction of different social groups (Braun, 2007). However it is not merely (in this case, urban architecture) professionals who deploy somatic expertise via powerful affects. Rather, these affects can be given life by (for want of a better word) ‘ordinary subjects’ who for whatever reason find resonance with those affects. This is not to say that the concept of community at Romsworth has been taken up precisely as the land vendor intended, nor with any obvious reference to molecularised, neuroscientific knowledges (and hence the limits of molecular theorising remain). Yet – given the high proportion of owner-occupied housing in Romsworth, much of it aimed at well-off families – the classed, affective capitalisation (Rose, 2007) evident in the definition of ‘vitality’ in the Task Force report has found fruition, along with any biopolitical knowledges that might underpin it. This is also not to say that everyone at Romsworth subscribes to ‘community’ in the same way. Nevertheless, the discursive-affective concept ‘community’ has em-powered a group of residents – themselves recursively occupying a relatively privileged standing – to enliven the biopolitical intent anticipated by the term in its abstract policy guise. My first navigational aid, then, centres around an attention to the ways in which residents may give life to discursive-affective concepts in practices that broadly resonate with the (biopolitical) intent of their expert originators; ‘biopolitics from below’ may, then, sometimes be far from oppositional or resistant. However, the becoming-lively of new urban architectures through such resonant practices may have multiple, ongoing implications. Critically, as Braun (2007) points out, the circulation of these kinds of affects can be exclusionary; indeed, the term ‘community’ implies marginalisation as much as cohesion (Silk, 1999). The next navigational aid turns to examples of exclusions writ by such community-affects; however, before these examples can be introduced, further analysis of the materialities of Sustainable Community infrastructures is required. Obduracy: contestations in ‘cleaner, safer, greener’ living places I have argued thus far that liveability is governed at mol(ecul)ar levels, before in some contexts being enlivened through patterns of discursive-affective resonance between urbanarchitectural professionals and selected residents. This section builds on that analysis to offer a second navigational aid that concentrates (initially) on the material constituents of urban architectures: obduracy. The argument will be that, in common with other expressions of biopower (but through their mol(ecul)ar constitution) the materialities of Sustainable Communities offer a particular disposition to the future. In some senses, urban-architectural practices are, like contemporary medical expertise, premised upon governance through optimisation: through professionalised techniques, it becomes possible to “predict [and...] enable intervention into [...] vital systems to reshape [...] futures” (Rose, 2007, page 16). Thus, diverse “geographies are made and lived in the name of pre-empting, preparing for, or preventing threats to liberal-democratic life” (Anderson, 2010, page 777). Those future threats could be many, but they share the distinction of being the target for anticipatory action in the present (Anderson, 2010). Such actions are spatialised in particular ways: from emergency planning exercises to anonymous data-backup warehouses (Adey and Anderson, 2011; Anderson, 2010). Whilst sharing much with other techniques of optimisation, the disposition to the future at work within Sustainable Communities policy also differs somewhat. Specifically, Sustainable Communities do not generally represent exceptional architectures that deal with classifiable emergencies (Anderson, 2010); nor are they characterised by pre-emptive measures focussed upon singular threats. Rather, urban architectures – and Sustainable Communities, specifically – denote combinative strategies that seek to pre-empt, prepare and offer precaution against a range of threats, determinate and indeterminate, banal and extraordinary, as well as a range of aspirations. These threats and aspirations – listed in the Sustainable Communities Plan (some of which are listed at the beginning of this section) – include flood events, biodiversity, social inclusion, community cohesion, housing shortages, crime, economic development and public conviviality. Moreover, unlike many forms of biopower these threats and aspirations are built-into the quotidian, domestic environments of people’s lives. Additionally, urban architectures pay strong attention to what are broadly understood to be ‘inanimate’ materialities (bricks, paving slabs, tarmac, concrete) rather than the more fleshy vitalities of animate/vegetal life that routinely figure in most biopolitical analyses (Bigham et al., 2008). Thus, urban architectures address the future in a different – albeit strongly related – style. I expand upon this contention below, with reference to the liveable public green-spaces anticipated by the Sustainable Communities agenda. A desire to secure the future brings with it an important contradiction. On one hand, any attentiveness to the future must contain the necessary flexibility to deal with the “fastchanging conditions” of contemporary life (Braidotti, 2011, page 11). On the other, those flexibilities remain obdurately fixed: it is only particular kinds of futures (and future-lives) that are deemed worth saving (Braun, 2007). Moreover, the anticipation of futures often relies on some kinds of fix-ing – of material infrastructures, of technologies, etcetera. This is a contradiction that has particularly dogged architects and planners. Once again, though, urbanarchitectural modes of governing life are rather particular: simply put, built forms cannot, usually, be as responsive as border guards. One response to this contradiction amongst architects has, for years, been to experiment with concrete forms that have in-built flexibility (Lerup, 1977). However, in the context of Sustainable Communities, urban architecture experts have related to the future through the reverse imperative – by demonstrating a hyperfinished holism that attempts to address contingency through master-planning. One can view Sustainable Communities as a mode of future-thinking that is more intensively obdurate than, for instance, emergency planning. Both Hettonbury and Romsworth have been heavily masterplanned – Hettonbury especially so, as noted in section II. The outcomes of this masterplanning in terms of the material design of public green-spaces have been particularly striking. The following analysis focuses on two examples: Sustainable Urban Drainage Systems (SUDS) in Hettonbury; public greenspaces in both communities. a. Sustainable Urban Drainage Systems in Hettonbury SUDS exist in many contexts: yet, in Hettonbury and other masterplanned communities, they are significant because they represent mol(ecul)ar forms of intervention and management that are intended to address future fears and aspirations obdurately. SUDS allow water and pollutants to be abstracted without either causing localised flooding, or dramatically altering local river flow. SUDS comprise several features (all taken from http://www.ciria.com/suds/index.html), of which three are instructive, because they operate at both molar and molecular scales. Pervious surfaces, such as porous asphalt, which maintain pre-development run-off rates. There is now considerable knowledge about the (often microscopic) requirements of materials required. For instance, a lay summary of hydrological research about pervious pavements indicates that “[o]nce the rainwater has entered the pervious surface it may flow out of the construction through the base to groundwater or [...] the waters will be intercepted by a drainage network and discharged from the sub-base [...]. Comparison of the outflow hydrograph [...] from a permeable surface with that for [...] an impermeable surface, reveals marked differences in performance. The porous surface and its sub-structure responds to rainfall much slower” (http://www.ciria.com/suds/hydraulic_performance.htm). Swales, which are vegetated “long shallow channels [which] provide opportunities for slow conveyance and infiltration (where appropriate)” (http://www.ciria.com/suds/filter_strips_and_swales.htm). Swales are not only effective for managing run-off but pollutants and (therefore) the possible colonisation of the swales by native species that thrive in wetland conditions: “[s]wales and filter strips are effective at removing polluting solids through filtration and sedimentation. The vegetation traps organic and mineral particles that are then incorporated into the soil, while the vegetation takes up any nutrients” (http://www.ciria.com/suds/filter_strips_and_swales.htm). Plate 2 shows an image of a swale in Hettonbury. Retention ponds, which, in Hettonbury, are arranged in a series on the downhill side of the development and act as a buffer before water eventually transfers to the nearby river. Ponds treat run-off by: “settlement of solids in still water – having plants in the water enhances calm conditions and promotes settlement; adsorption by aquatic vegetation or the soil”. In addition, “ponds and basins offer many opportunities for the landscape designer. Basins should not be built on, but can be used for sports and recreation. Permanently wet ponds can be used to store water for reuse, and offer excellent opportunities for the provision of wildlife habitats. Both basins and ponds can be part of public open space” (http://www.ciria.com/suds/basins_and_ponds.htm) PLATE 2: A SWALE AT HETTONBURY. The above details are necessary because they illustrate several important points. First, that urban architectures are increasingly subject to the same “technologies of optimization” and domain-specific “experts of life itself” (here, hydrologists) as the more familiar field of biomedicine (Rose, 2007, pages 15 and 27). Second, that whilst I have thus far foregrounded how the production of liveability is located in a molar register (for instance, in Audit Commission [2005] liveability indicators), clearly, these hydrological technologies are also operating at the molecular scale. They are concerned with the flow of water through microscopic pores, with the filtration and sedimentation of pollutant solids, and so on. Third, then, I suggest that urban architectures are combinative because they co-mingle molar and molecular biopolitics: they are mol(ecul)ar. They seek to create and regulate bio-diverse drainage ponds that will simultaneously constitute safer, greener public spaces for the ‘conviviality’ of an entire community; and, they extend beyond commonly-accepted lifematters into the more obdurate materialities of bricks, mortar, paving slabs, etcetera. SUDS, then, represent potentially hyper-modulated versions of “biological communities assembled through the dense comings and goings of urban life” (Hincliffe and Whatmore, 2006, page 123). Thus, urban architectures (of which SUDS are one component), respond to the fragility and contingency of life through a logic of combination and obduracy. On the one hand, they combine the seeming obduracy of their material constitution at a molar scale with the responsiveness of some materials at a molecular level (also Bennett, 2010). On the other hand, they combine the complex process of Enquiry by Design (explained in section II) with its eventual outcome: a set of design criteria that over-codes and, crucially, fixes the material landscape to such a degree of horizontality that molecular details of the SUDS obtain as much significance as ideal variations in housing design-types (compare Jacobs, 2006). b. Public greenspaces in Hettonbury and Romsworth Tallying with New Labour’s guidance on ‘liveable’ urban spaces, it is notable that in much generally-available SUDS guidance, biodiversity is categorised with ‘amenity’ (i.e. community resource)7. The benefits of a SUDS are not merely felt in the management of water, pollutants and the like, but in their ability to provide precisely the “cleaner, safer, greener” public spaces that make a community ‘liveable’. The overall impression is that the SUDS may both engender and improve life-itself – both natural and social, at both molar and molecular scales. However, as may be apparent by now, public green-spaces – which include SUDS, but also include patches of woodland, grass, parks and playgrounds – are characterised by complexity, both in terms of their planning and the multiple ambitions attached to them. However, it these very combinative qualities that, in places such as Hettonbury and Romsworth, have led to (especially intergenerational) social tensions. It is here that the analyses presented in this section and the last – in terms of discursive-affective resonances and material obduracy – come together. In Hettonbury and Romsworth, in addition to SUDS, there are small parcels of grass (see Plate 1) or woodland. Talking to residents – whatever the legal reality – there is lack of clarity about who is responsible for such green-spaces: the local authority, the developer, the local housing authority, the community themselves, or some combination. This ambiguity has arisen – in part – because of the dense, complex ways in which these spaces were originally masterplanned. From our observational data, these ambiguities have begun to work themselves out in various, often contradictory ways. In Hettonbury, for instance, we observed residents taking responsibility for managing small patches of grass and SUDS (mowing, picking up litter) which are clearly not part of their own property. In both communities, young people use SUDS, patches of grass, woodland, squares and other public spaces for a variety of games or hanging out. Thus, children are using them – more-or-less – in ways that chime with the objectives of planners. 7 See, for instance, http://www.sudssource.org/paper5.htm; and http://www.susdrain.org/deliveringsuds/using-suds/benefits-of-suds/amenity-and-biodiversity.html Yet these green spaces have also become contested – particularly between young people and adults. In both communities, young people told us that they had been explicitly told to move on from some patches of grass and woodland because adult residents had claimed they were ‘private’: “They [younger children] go in the woodland, like all the time, they're like, they build swings in there and they make their dens but then there's this really funny bloke, he, he moved [...] here and, and he came and told them off and was like that's private land you're not allowed to play in here” (Oliver, thirteen years old, Hettonbury) Strikingly, there was no evidence that this was ‘private land’. Thus, uncertainties about ownership had enabled some adults to make, and to try to enforce, claims about particular patches of green space. As children’s geographers have repeatedly shown, such intergenerational tensions in public space are common (Valentine 1996; Matthews et al., 2000). Apparently, in Hettonbury, an effect of a desired-for obduracy – via the combinative logic of masterplanning – has led to ambiguity, which in turn has led to (adult) residents seeking to further fix and foreclose the use of public green-spaces. In Romsworth, however, the privileged, discursive-affective status of community (discussed as part of the previous navigational aid) led to heightened contestations around green-spaces. From our observations, young people frequently used these spaces (such as that in Plate 2) for playing games and hanging out. However, many young people felt like they could not spend significant time in any one green-space – feeling compelled to move themselves on: “Lily: I don’t know, it’s really strange, [...]. It’s (Romsworth) just got different rules I guess and people have just adapted to them rules while you’re in the village. Like, when, if I go into [a nearby village] then yeah, I would hang around the shop, it’s just different ways, I dunno. I: And are those rules, has anyone ever said [...]? Lily: No, it’s just expected. It’s an understanding, init? You kind of expect it. And it’s like, people wouldn’t want to see us hang around the shop. That’s why we go on the field” (Lily, 16 years old, Romsworth) Here, then, the discursive-affective resonance between Romsworth’s developers and its (more powerful) adult residents has created community affects that, despite the community’s relative newness, repetitively and obdurately “normalise acceptable citizenly behaviours and idealisations of the good citizen” (Pykett, 2012, page 37). Most striking was that young people felt they should move, doing so without being explicitly asked – an unsaid ‘understanding’ (compare example from Hettonbury; also Matthews et al., 2000). Beyond pervasive, negative attitudes to young people in the UK – which young people themselves recognised – it transpired that there is something different about Romsworth, which young people compared with other villages. Several young people spoke about the atmosphere in Romsworth feeling “claustrophobic” – as if young people spoiled the careful but very particular (visual) aura of community that both urban professionals and selected adult residents worked so hard to forge. As James, a sixteen-year-old resident put it: “we spoil the pride of Romsworth”. Here, then, is what William Connolly (2005, page 869) terms a “resonance machine”. At Romsworth, this is not a resonance of evangelical Christianity/Cowboy capitalism, but of the combinative logics of ‘liveability’ between housebuilders, planners and (early) adult residents, whereby community is an “ethos suffusing the resonance machine [that is] expressed without being articulated” (Connolly, 2005, page 869). Thus – at least in Romsworth – the obdurate materialities of public green-spaces are combined with the resonant, discursive-affective construct of ‘community’ in ways that render ‘liveability’ a social and material achievement. That achievement is not only gained through the somatic expertise of urban-architectural professionals, but taken up by non-experts – selected residents – who configure an emergent resonance machine to implicitly exclude groups of young people along traditional identity fault-lines (compare Braun, 2007). Dissonance: creating life-itself in green-spaces In contradistinction to the previous section, the third navigational aid centres around the very presence of residents – and, especially young people – as a constitutive element of the ongoing, emergent life of new urban architectures (see Horton and Kraftl, 2006). This is not meant to be a romanticised observation about young people’s agency. Rather, the point is a political one (with a small ‘p’). To exemplify this point, three illustrative ‘vignettes’ will be employed: two from Hettonbury, one from Romsworth. The first vignette is the story of The Square, in Hettonbury, as told by several residents. The Square is a public space provided by one of the developers. It is typical of the kinds of public spaces created under New Labour: an open space with ground-mounted fountains (switched on in summer), amphitheatre-style steps, water channels, and lollipop trees around the perimeter. The Square was completed during the early stages of Hettonbury’s development. It was subsequently surrounded by fences with the intention that it would be opened to the community (as a ‘gift’ from the developer) when it was enclosed by housing. For various reasons, the housing surrounding The Square was not completed until 2012. In the intervening years, young people from Hettonbury entered The Square through gaps in the fence and began to use it for skateboarding and BMX-ing. They made use of builders’ materials and advertising hoardings to make impromptu obstacles. Their presence caused concern amongst residents and developers; however, the developers’ eventual response was to open The Square for community use – several years before the surrounding housing was completed. The Square rapidly became a popular public space in Hettonbury, enjoyed by residents of all ages. The second vignette relates to a patch of woodland, planted at the northwestern extreme of Romsworth when building began in the early 2000s. In Romsworth, children told us of how they had played there, building dens and playing games: “I: So would you say you feel attached to this place [woodland]? Evan: Yeah, I mean the amount of games I've played here, hide and seek, like Star Wars and Knights and oh everything [...] one time our friends came over and we sort of camped out because I remember when, when the grass was really long [...] we make a makeshift little house out of sort of the grass [...] the grass counted as walls and we, pretty much, when we tread it down it stays down, it was really fun and I miss that because we couldn't really do that anymore because the grass [is cut]” In this and subsequent discussions, older young people recounted how they had physically grown-up at the same time as the trees had matured and the community’s housing had been completed. For them, memories of playing in these woods were important to emerging senses of place-attachment, and which were indistinguishable from the gradual maturation of the woodland and the growing up of the community – both materially and socially. Ironically, Evan and his friends engaged in the kinds of play that many adults claim have been lost amongst contemporary British youth, in the very kinds of spaces where some adult residents were wary of children’s presence. The third vignette comes from Hettonbury, although equally applies to all four case study communities from our research. In Hettonbury, the majority of children told us that, as part of their free time, they spent time ‘just walking’ around the community (see also AUTHOR, forthcoming): “I like just walking round because it's nice to just like see people [...] sometimes we're in my friend Anna’s house [...] sometimes near her house [...] but we, we kind of like, we kind of like just walk like anywhere, any route really” (Colette, ten years old, Hettonbury) Colette and her friends often walked around Hettonbury, almost aimlessly: sometimes stopping to play a game; sometimes bumping unexpectedly into other groups of young people; sometimes stopping to talk to adults; sometimes, “just walking”. In one sense, these young people constituted the very social life – the liveliness – of Hettonbury in a way that had few direct referents to concepts of ‘liveability’. In others, their “just walking” was, like the skateboarding in The Square, afforded by the very design of those spaces under the auspices of ‘liveability’. Yet, most tellingly, Colette and her friends used their very presence in public spaces to develop intimate local knowledges that supported acts of what Bennett (2001, p.131) calls “presumptive generosity”: “of rendering oneself more open to […] other selves and bodies and [being] more willing and able to enter into productive assemblages with them”. “Sarah: Yeah, there's been two or three people that have just moved in last week. Colette: there's this little girl down the lane but we ain't knocked for her yet because they ain't settled in and they've still got moving in to do so, because we keep seeing lorries of stuff coming down” (Sarah and Colette, eleven years old, Hettonbury) Sarah and Colette were intimately aware of the arrival of new residents but waited patiently until the right moment before welcoming them. As noted above, the appearance of young people in Hettonbury’s public spaces – especially those engaged in seemingly aimless walking – appears threatening to adults and the conceptions of ‘liveability’ that they have bought-into in Sustainable Communities (for comparisons with South African and New Zealand contexts, for instance, see Benwell, 2013; Witten et al., 2013). However, Colette and her friends were engaged in everyday mobilities that were entangled with presumptive acts of welcome that most adults would find heartening, if not, actually, ‘convivial’ In these moments, the mol(ecul)ar biopolitics of liveability were combined with the ongoing becoming-lively of new urban architectures in ways that could be characterised as “dissonance” (Braidotti, 2011, page 20). Superficially, the stories of The Square, the woodland and of ‘just walking’ appear to exemplify a classic manoeuvre of childhood studies scholars: to contrast (adult) planners’ intentions with (young) inhabitants’ everyday experiences, thereby observing intergenerational tensions (Hopkins and Pain, 2007). Drawing on my discussion of community-affect in Romsworth (above), clearly, such tensions exist. In addition, however, young people’s agency could be viewed in two ways. Firstly, as has been well-documented elsewhere, as a kind of implicit, tacit, micro-political action, whereby (young) people’s everyday lives spill over into sometimes unanticipated acts of citizenship that benefit a wider community (Kallio and Häkli, 2011). Secondly, following Braidotti (2011), it could be argued that beyond any specific micropolitical agency, young people are productive of certain kinds of life in Sustainable Communities in ways that are both resonant with but also disjointed from professionalised, urban architectural appeals to ‘liveability’ and its consequent fixing. That is, they are dissonant, rather than resistant: most Hettonbury residents were displeased about young people ‘breaking in’ to The Square, but they also acknowledged they had contributed to a-live-liness – vitality – by causing its early opening in a way that has benefitted adults and children alike, and has led to use of The Square in ways that chime with ‘liveability’. Hence, this navigational aid is a plea for greater attention to dissonance, which could equally be performed by adults as children, but which is crucial to the becoming-lively of places like Sustainable Communities. The vital-materialisms of Jane Bennett and Rosi Braidotti may provide further interpretive and navigational aids. For, as they insist on co-implications of “thing-power” (Bennett, 2010, page 2) and/or “zoe – nonhuman life” (Braidotti, 2011, page 16) with and as human sociability, they make room for alternative figurations of vitality that sit somewhere between the spiritual Romanticism of “those “naive” vitalists”, the ostensibly life-less, “mechanistic model of nature assumed by the “materialists”” (Bennett, 2010, page 63), and the “lame quest for angles of resistance” that (in the example of some oppositional feminist politics) “perpetuates flat repetitions of dominant values of identities, which [they claim] to have repossessed dialectically” (Braidotti, 2011, pages 18 and 40). Through their “affirmative politics” (Braidotti, 2011, page 267), these two theorists evoke a kind of vitality that maybe grasped through witnessing the presence of entanglements of young people/building materials/trees (etcetera) in Hettonbury and Romsworth (also Lee and Motzkau, 2011). These are, of course, the very same materials and spaces that are meant to be obdurately fixed and resonate with those adults who buy-into Sustainable Communities. Yet, it is through these kinds of (re)combinant bio-social agency that ‘new communities’ obtain intensifying memories, attachments, meanings and vitalities: “a conception of living cities that resists this familiar architecture of urban analysis [‘urban greening’ programmes] in at least three ways: cities are inhabited with and against the grain of expert designs [...]; urban inhabitants are heterogeneous [...]; urban liveability involves civic associations and attachments forged in and through more-than-human relations” (Hinchliffe and Whatmore, 2006, page 124, emphases added). These associations, as Hinchliffe and Whatmore put it, correspond with the notion of dissonance. Significantly, the three vignettes above do seem to indicate the success of ‘liveability’, as described in Sustainable Communities policy-making: of Hettonbury and Romsworth as well-designed, safe, liveable places that, for instance, afford children’s presence outdoors. This may be true, but only to the extent that ‘liveability’ is co-implicated with/in the heterogeneous attachments, activities and lines young people trace around their communities as they foster senses of live-liness that may conform with, conflict with, and exceed the governance of life-itself in new communities. Thus, dissonance may be understood as the production of a certain live-liness: something modestly affirmative and productive of perhaps temporary, minor, but concrete steps that run both with and against the grain of mol(ecul)ar urban architectural practices, and that make life (better) in places like Hettonbury and Romsworth. IV Conclusions This paper has attended to urban architectures of life-itself in Sustainable Communities. Like other attempts to govern life-itself, Sustainable Communities are notable for an intense and explicit attention to life-matters – specifically in creating ‘liveable’ urban economies, spaces and socialities. However, Sustainable Communities differ qualitatively from (for instance) the molecuralisation of biomedical expertise or emergency planning. Critically, experts’ emphasis upon masterplanning and micromanagement has positioned urban architectures within molar and molecular (mol[ecul]ar) concerns, through combinative strategies that sought to fix multiple social-natural processes via the more-or-less obdurate materialities of urban architectures. In conjunction with these scalar implications for theorisations of life-itself, the paper contains some broad implications for geographies of architecture (Jacobs, 2006; Jacobs and Merriman, 2011; Kraftl, 2009). It has demonstrated not only that urban architectures are implicated in the planning and experience of life-itself, but how. The three navigational aids presented in this paper offer a starting point through which geographers of architecture might weave together an attention to political-economic imperatives and inhabitation (Lees, 2001), affect and emotion (Rose et al., 2010), and materiality (Jacobs et al., 2007) towards an alternative, critical, conceptual language for understanding particular kinds of new urban architectures, like Sustainable Communities. The concept of resonance affords a sense not only of how both somatic experts and ‘ordinary subjects’ take-up and run with affective-discursive regimes, such as notions of ‘liveability’ and ‘community’. The concept of obduracy captures the ways in which urban architectures address the future rather differently from other efforts to govern life-itself – most notably through fixing the design of public green-spaces in ways that themselves resonate with notions of liveability. Taken together, resonance and obduracy may serve to further exclude groups traditionally marginalised in older communities (such as young people): clearly, there is further work to be done in this vein. The concept of dissonance opened out a series of three – of many – ways in which residents rub along with and may produce their own senses of vitality and liveliness. Certainly, these very same forms of play, creativity and micropolitical action may occur in any community. Yet, this paper has begun to exemplify how different registers of life-itself – life as planned ‘liveability’, and, life as playing, walking or welcoming – may intersect in dissonance with one another in places where the governance of life-itself is so clearly articulated. Thus, future geographies of architecture may take cues from this paper in deploying these three – and other – navigational aids in critically interrogating how built forms maybe complicit in the governance of life-itself, and in its (resonant and dissonant) everyday experience. They may also examine further the combination of molar and molecular scales in such contexts, rather than emphasise either the former (as per Frandsen and Triantafillou [2011]) or the latter. There also remains much further work to open out manifold ways in which urban architectures may be complicit in various forms of biopower, in various historical and geographical contexts. On one hand, studies with greater attention to the historical specificity of the principles of Garden Cities, neo-traditional urbanism, modernist planning, and the like, could be framed within contemporary analyses of life-itself to better assess the relative novelty of Sustainable Communities and other contemporary urban architectures. Clearly, architects and urbanists (like Jacobs, 1961) have had much to say about the sociability and conviviality of urban places in the past. Yet it is important to note that there has been a certain intensification of attention to the particularities of life-itself, both through acts of naming and through the combinative, technologically-detailed, master-planned logics anticipated by notions such as ‘liveability’. On the other hand, important critiques are emerging around ‘eco’-architectures, which building styles/technologies are proliferating around the world (Pickerill, forthcoming), yet whose relationships with attempts to govern life-itself are relatively unknown. Moreover, SUDS are becoming increasingly familiar technologies in many geographical contexts; notions such as ‘liveability’ are being deployed not only to compare but to plan urban places outside the UK8; within the UK, renewed attention upon large-scale house-building has led to a revival of interest in the potential of 8 See, for instance, the Liveable Cities blog (http://liveablecities.org.au/) and annual conference for “professionals in the public and private sector to examine the challenges and solutions needed to develop the Liveable Cities of tomorrow” (http://healthycities.wordpress.com/, last accessed 10th June 2013) Garden Cities9 to offer inspiration for the master-planning of new communities. Therefore, the co-implication of urban architectures with efforts to govern life-itself – and with everyday acts to take-up, resist or evade those efforts – requires ongoing, critical attention. Acknowledgments I am grateful to two anonymous referees for their constructive and patient comments. I acknowledge the financial support of the UK Economic and Social Research Council, grant number RES-062-23-1549. Finally, I wish to thank my colleagues from the ‘New Urbanisms, New Citizens’ research project – Pia Christensen, John Horton, Sophie Hadfield-Hill and Sarah Smith – for comments on an earlier draft and for generating the empirical data upon which this paper is based. This paper is for Adam. References Adey P, Anderson B, 2011 “Event and anticipation: UK civil contingencies and the spacetimes of decision” Environment and Planning A 43 2878-2899 Amoore L, 2006 “Biometric borders: governing mobilities in the war on terror” Political Geography 25 336-351 Anderson B, 2010 “Preemption, precaution, preparedness: anticipatory action and future geographies” Progress in Human Geography 34 777-798 9 See, for instance, the UK Town and Country Planning Association’s ‘Re-Imagining Garden Cities for the Twenty-First Century’ initiative (http://www.tcpa.org.uk/pages/garden-cities-re-imagining-garden-cities-forthe-21st-century-166.html), and Deputy Prime Minister Nick Clegg’s speech to the National House building Council on the same topic (https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/deputy-prime-ministers-speech-tonational-house-building-council) Anderson B, 2012 “Affect and biopower: towards a politics of life” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 37 28-43 Audit Commission, 2005 Local quality of life indicators (Audit Commission, London) Bennett J, 2001 The Enchantment of Modern Life (Duke UP, Durham) Bennett J, 2010 Vibrant Matter (Duke UP, Durham) Benwell M, 2013 “Rethinking conceptualisations of adult-imposed restriction and children’s experiences of autonomy in outdoor space” Children’s Geographies 11 28-43. Bingham N, Enticott G, Hinchliffe S, 2008 “Guest editorial: biosecurity: spaces, practices, and boundaries” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 40 1528-1533 Braidotti R, 2011 Nomadic Theory (Columbia UP, New York) Braun B, 2007 “Biopolitics and the molecularization of life” Cultural Geographies 14 6-28 Den Besten O, Horton J, Kraftl P, 2008 “Pupil involvement in school (re)design: participation in policy and practice” Co-Design 4 197-210. Department for Communities and Local Government [DCLG]/Home Office, 2005 Citizen Engagement and Public Services (HMSO, London) Connolly W, 2005 “The Evangelical-Capitalist resonance machine” Political Theory 33 869886 Foucault M, 1978 The History of Sexuality, Vol 1 (Penguin, London) Frandsen M, Triantafillou P, (2011) “Biopower at the molar level: liberal government and the invigoration of Danish society” Social Theory & Health 9 203-223 Hall P, Ward C, 1998 Sociable Cities (Wiley, Chichester) Hinchliffe S, Whatmore S, 2006 “Living cities: towards a politics of conviviality” Science as Culture 15 123-138 Hopkins P, Pain R, 2007 “Geographies of age: thinking relationally Area 39 287-294 Horton J, Kraftl P, 2006 “Not just growing up, but going on: children’s geographies as becomings, materials, spacings, bodies, situations Children’s Geographies 4 259-276 Jacobs J, 1961 The Death and Life of Great American Cities (Random House, New York) Jacobs J, 2006 “A geography of big things” Cultural Geographies 13 1-27 Jacobs J, Merriman P, 2011 “Practising architectures” Social and Cultural Geography 12 211-222 Kallio K, Häkli J, 2011 “Are there politics in childhood?” Space & Polity 15 21-34 Kraftl P, 2006 “Ecological buildings as performed art: Nant-y-Cwm Steiner School, Pembrokeshire” Social and Cultural Geography 7 927-948. Kraftl P, 2009 “Living in an artwork: the extraordinary geographies of everyday life at the Hundertwasser-Haus, Vienna” Cultural Geographies 16 111-134 Kraftl P, Adey P, 2008 “Architecture/affect/dwelling” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 98 213-231 Kraftl, P, Christensen P, Horton J, Hadfield-Hill S, forthcoming 2014 “Living on a building site: young people’s experiences of emerging ‘Sustainable Communities’ in England”. Geoforum. Kraftl P, Horton J, 2007 “‘The Health Event’: Everyday, Affective Politics of Participation” Geoforum 38 1012-1027. Lee N, Motzkau J, 2011 “Navigating the biopolitics of childhood” Childhood 18 7-19 Lees L, 2001 “Towards a critical geography of architecture: the case of an ersatz colosseum” Ecumene 8 51-86 Lees L, 2003 “Visions of ‘Urban Renaissance’: the Urban Task Force Report and the Urban White Paper, in Urban Renaissance? Eds R Imrie, M Raco (Policy Press, Bristol) pp 61-82 Lerup L, 1977 Building the Unfinished (SAGE London) Nally D, 2011 “The biopolitics of food provisioning” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 36 37-53 Office of the Deputy Prime Minister [ODPM] 2002 Living Places: Cleaner, Safer, Greener (HMSO, London) Matthews H, Limb M, Taylor M, 2000 “The ‘street as thirdspace’”, in Children’s Geographies Eds S Holloway, G Valentine, G (Routledge, London) pp 63-79 Office of the Deputy Prime Minister [ODPM] 2003 Sustainable Communities: Building for the Future (HMSO, London) Paterson M, 2011 “More-than-visual approaches to architecture: vision, touch, technique” Social and Cultural Geography 12 263-281 Pickerill J, forthcoming “The buildings of Ecovillages: exploring the processes and practices of eco-housing” RCC Perspectives Pykett J, 2012 “Making ‘youth publics’ and ‘neuro-citizens’: Critical geographies of contemporary education practice in the UK”, in Critical Geographies of Childhood and Youth Eds P Kraftl, J Horton, F Tucker (Policy Press, Bristol) pp 27-42 Raco M, 2005 “Sustainable development, rolled-out neo-liberalism and sustainable communities” Antipode 37, 324-346 Raco M, 2007 Building Sustainable Communities (Policy Press, Bristol) Rogers R, 1999 Towards an Urban Renaissance (Urban Taskforce, London) Rose G, Degen M, Basdas B, 2010 “More on 'big things': building events and feelings” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 35 334-349 Rose N, 2007 The Politics of Life Itself (Princeton UP, Princeton) Silk J, 1999 “The dynamics of community, place and identity” Environment and Planning A 31 5-17 Thrift N, 2004 “Intensities of feeling” Geografiska Annaler B 86 57-78 Town and Country Planning Association [TCPA], 2011 Re-imagining Garden Cities for the 21st Century (TCPA, London) Valentine G, 1996 “Angels and devils: moral landscapes of childhood” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 14 581-599 Valentine G, 2008 “Living with difference” Progress in Human Geography 32 323-337 Wahlberg A, 2009 “Bodies and populations: life optimization in Vietnam” New Genetics and Society 28 241-251 Witten K, Kearns R, Carroll P, Asiasiga L, Tava’e N, 2013 “New Zealand parents’ understandings of the intergenerational decline in children’s independent outdoor play and active travel” Children’s Geographies 11 215-229.