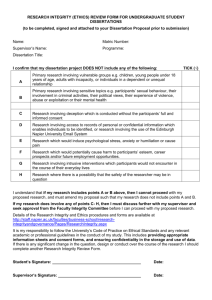

MTHMS15/101/2012 DEPARTMENT OF CHRISTIAN SPIRITUALITY

advertisement