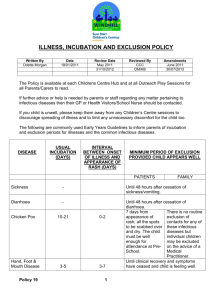

Study of the barriers for the scholar and social

advertisement

THE CONSTRUCTION OF SOCIAL EXCLUSION PROCESS IN YOUNG PEOPLE: A BIOGRAPHICAL-NARRATIVE APPROACH. TERESA SUSINOS UNIVERSITY OF CANTABRIA SPAIN susinost@unican.es Introduction The current paper intents to describe the basic theoretical principles that lead two researches we are carrying out in the university of Cantabria and the university of Sevilla1. The purpose of this research is to know and describe the existent barriers for the educative and social participation of young people affected by a situation of social and cultural exclusion. In particular we are interested in the way these barriers are expressed and lived by the own people above mentioned. With this aim, we have used different biographical-narrative methods. There are various elements that singularise this research on social inclusion such as we are trying to state bellow. These elements can be summarised as follows: 1. 2. 3. Exclusion is a wide and complex phenomenon of structural character that affects both, individuals and different social groups. Traditionally the study of exclusion has been independently talked for each social group and in particular, the group of disabled people has been constantly ignored by sociological studies. However, one of the main objectives of the current research is to highlight the common aspects within the path towards exclusion that can be seen in the different social groups (Parrilla, 2002; Susinos, 2002). Exclusion is a phenomenon socially constructed, therefore it does depend not so much on the individual conditions, but on the social and institutional organisation systems that impose barriers or restrictions to the social participation of certain groups or individuals. Thus, exclusion is a process that can be described according to its diachronic dimension, by pointing out the fundamental milestones in such way, which we will call herein barriers for inclusion. Exclusion can be studied from the point of view of the affected people, narrated in first person. Against the most external and expert methods to know about exclusion, in our study we are interested in knowing about exclusion in first person. Thus, we will use biographical-narrative 1 Parrilla, A. y Susinos, T. (dirs.) (2003).The construction of the social exclusion process in young women: origin, forms, consequences and implications for training. I+D Project. Instituto de la Mujer. Expte. 90/02 0000245 1 010112003. Parrilla, A. y Susinos, T. (dirs.) (2005) The construction of the social exclusion process in young people: A guide for the detection and assessment of exclusion processes (Cantabria and Sevilla). I+D+I 2004-07 Department of Education . Ref.: SEJ2004-06193-C02-02/EDUC. techniques, since they are the ones that best allow us to came close to such biographical contents. So, these main principles are specified in our study through some epistemological and methodological decisions that are summarised in the following table: SOCIAL EXCLUSION How it is… It affects different groups through common ways It is a social construction No individualisati on How do we study it… Interdisciplinary approach Reasons why we study it in this way To get a complex knowledge Study of the barriers for participation To reveal aspects within the social organisation that generate exclusion It generates excluded identities Diachron ic view Biographicalnarrative approach “giving voice” to the excluded persons Empowerment Following, let see how the principles above mentioned are understood and developed in our research. A wide idea of social exclusion: various groups, similar social barriers. Social exclusion is a structural phenomenon (not circumstantial), which is increasing in our societies and that it is related to certain social processes that lead to the isolation of certain groups and individuals while they are marginalized by the organisations and institutions in which society is organised. This process entails a lost of the sense of belonging for the individual, as well as the denial of certain economical, social, political, cultural and/or educational rights and opportunities (Tezanos, 2001a). This meaning of social exclusion has strong connections with the concept of oppression, as it has been defined by Young (2000). For his part, Manuel Castells (1998) reminds us that “social exclusion is a process, not a condition. Therefore its frontiers change, and who is to be excluded or included can vary with the time, depending on education, demographical characteristics, social prejudices, business practices and public politics”. Actually, exclusion could be also understood from its opposite concept of social citizenship where we also find an internal or individual process of degradation and an external or social process of fracture or removal of several groups or communities2 . For this reason the term is used with regard to “All those persons that, in a certain way, are out of the vital opportunities that define the achievement of a full social citizenship in the horizons of the end of the twentieth century” (Tezanos, 2001b, p138) Taking the previous definition of social exclusion as a starting point, it is necessary to recognise other social groups as excluded, beyond the ones traditionally proposed by sociology. According to what stated by Slee (1997), up to now from the social sciences the attempts for a joint construction of the phenomenon of social exclusion have been focused on what the author identifies as: “class, culture, gender”, leaving the question of disability out. On the contrary, we defend herein an essential unity defined by the concept of exclusion we have adopted and which also includes the group of disabled people, traditionally under-recognised in the studies about social exclusion. Therefore, the groups of young people who find themselves in a situation of social and educative inequality and that are finally taking part in this research are the following: - Young people belonging to underprivileged social classes with limited access to culture and information and with a precarious economy. - Young people belonging to not dominant cultures and ethnic groups: ethnic minorities, immigrants, and in general groups whose reference cultures are ignored by the social or educative leading culture. 2 The idea of social exclusion we defend is related to three other wide sociological concepts that are combined in a different way within every group or individual: the separation of the leading standards in society (social deviation, social marginalization, or social segregation), the idea of poverty or lack of resources sufficient enough to live in a concrete society and the idea of alienation from social processes, of lack of participation. - Groups of people with disabilities and educative needs, with special difficulties to accede to the social and scholar learning and to progress adequately at school. As stated above, in our research hereby we understand that the process of social exclusion of people belonging to the previous groups (due to class, culture, gender or disability) has numerous features in common and is constructed through parallel channels. This statement leads us to recognise together with Slee (1997) that it is a must for scientific research to contribute to the construction of a new theoretical frame through investigating the epistemological and methodological connexions towards the definition of identities of groups in situation of inequality or risk of exclusion for cultural, gender, social or disability reasons (in the school, in society, in educational politics, etc). That is why we believe it must be called into question the independent construction (from different disciplines with no connexions among each other) of the discourses on exclusion, since, at the very best, each of them offers an incomplete view of the phenomenon. From the above it may be deduced that a multidisciplinary approach to the phenomenon of social exclusion is necessary, given that such a complex phenomenon can’t be grasped just from the positions of traditional disciplines. On the other hand, and according to Morin (2003), the traditional prevalence of disciplinary research has an effect on the knowledge itself, remaining distorted or incomplete while destroying at the same time solidarity and responsibility. Specialised disciplinary knowledge prevents us from joining, placing the information within its natural context and we loose the capacity to globalise, to appreciate every knowledge as a part of a wider knowledge, when the conditions for any pertinent knowledge are precisely contextualisation and globalisation Likewise, the compartmentalised and parcelled way in which specialist and technical experts work (but also administrations and bureaucracy while designing and managing social politics) are the cause of the progressive destruction of solidarity and responsibility, since if we don’t face the problem as a whole, we will loose at the same time the sense of responsibility and we will end up limiting our responsibility to our small professional task Therefore, the transdisciplinary thinking leads us towards an ethic of comprehension, and without it no civilisation is possible. Exclusion is a process socially constructed: The process of formation of excluded identities Talking about social exclusion as a phenomenon socially constructed implicitly sums up two important options of our research: a) An open rejection towards individual explanations of social exclusion, based on particular psychological characteristics or other personal features of the subjects, which are presented as differences with a natural biological base or due to certain physical characteristics of the subjects. As an effect of such individual or psychological model the social phenomena became naturalised in such a way that the differences of social nature (due to a particular way of organizing society and institutions) appear to us as natural, indisputable and eternal. Thus, it is implicitly understood that such phenomena cannot be changed due to its “universal and truth” nature. On the contrary, we start from the assumption of the basic premise of social responsibility while creating social exclusion and therefore the core of the research consist in detecting and analysing the obstacles and restrictions imposed by the institutions and social organisation in general to the individuals or groups and that provoke as a result that these individuals or groups find themselves left out of social participation. So, in the line of Disability Studies developed following the social model of disbility, our research focuses on the study of social barriers for the participation ( named “disabling barriers” by Finkelstein), such as they are described by the own people affected. This intends, according to Zarb (1997), to explain the way and the extend to which economical and social institutions contribute to the promotion of specific ways of exclusion experimented by individuals or concrete social groups. b) Likewise we hereby intend to study the construction of exclusion in a diachronic way, and also to know the historical course through which the subjects construct their own excluded identities (disabled, “bad students”, foreigners, unemployed people or “unemployable” identities). It is precisely this constructed identity and the different milestones of this process what we intend to know from the own affected. Frequently social exclusion has been analysed as a fixed picture, describing the present state of certain persons or groups and stating their situation of social alienation in the educational, cultural, economical and social processes. However, we must keep in mind that social exclusion is a process which can be sometimes slow and subtle and which is not always linear. Therefore, we are keen on analysing the exclusion in its dynamic dimension, as a process through which young disabled people or underprivileged social groups go on finding in the course of their lives successive barriers that act as obstacles or hitches for the full social participation and that finally “incapacitate” them, exclude them or segregate them. The interest of studying the social exclusion from the point of view of the own people affected, trough their own words As we keep on stating, the main interest of this research on knowing the points of view and the experiences of those who are socially excluded is not very common in social research and it is particularly unusual within the studies with regard to the group of disabled people (French and Swain, 2000) However, as Barton and Oliver (1993) pointed, the understanding of exclusion brings up the need of analysing not only the construction of the exclusion process itself (the mechanisms and ways that lead to it) but the personal and subjective dimension of the process (the experience of exclusion itself, the interpretation, opinions and perspectives of people living in a situation of exclusion). This study of exclusion “from inside” is also interesting because the official rhetoric not always matches up with the images these people have from themselves (Barton, 2000). In this respect, from the point of view of the social workers, social services institutions and health and educational workers, it is important to bear in mind this sentimental and experimental dimension of the users too much times ignored in the planning of social and educational politics. This research adopts a biographical-narrative approach with the aim of giving voice to the protagonists. Narrative techniques have been used for a long time in several social sciences (anthropology, linguistics, ethnography) and particularly from the post-modern and feminist perspective3. Essentially this methodological model is based on the idea that “human beings read and interpret their own experience as well as the experience of others in the form of a story (…) narrative structures (…) constitute the frame through which human beings endow their world with meaning” (Bolivar et al. 2001,p.21). Thus, our actions and other’s are understood as texts to be interpreted that provide our experience with a meaning. The language allows us the construction of meaning of our thoughts, feelings and actions. For this reason, the way in which individuals retell their story (what they underline, what they omit, their position as main figures or victims) shapes what individuals may declare about their own lives. In fact, Bruner himself (who contributed in a decisive manner to consolidate narrative investigation in psychology) stated that “The crucial moments in life are not caused by real facts, but by the reviews carried out in the account used by everyone while talking about their lives and the self” (Bruner and Weiser, 1995) Therefore the autobiographical narration done by these young people constitutes a kind of “personal archaeology” of their own story. This provides the informing person with a principal and not very frequent role in the research, a co-researcher status of his own life. Following the previous ideas about the potentiality of the biographical-narrative methodology, our study makes use of several techniques that lead to the exploration of everyone’s narrative activity with regard to the barriers young people find most significant in their own story of social and scholar exclusion. This way of approaching exclusion known as participative approach analyses exclusion in first person, from the perspective of persons belonging to marginalized groups. In our opinion, the biographical-narrative methodology we use in this research is the most reliable one. We find that in our case autobiographical narration has a double function: a) The interest in “giving voice”, in analysing and describing forms of collective representation of excluded groups, in bringing out hidden or marginalized stories. This first dimension is emphasised by the oral history and the social interactionism (eg. Goffman). 3 In particular this methodology links with the post-modern principles of rejection of the meta-narratives and the universals, as well as with the extolment of the peculiar, different and typical of every human being. At this point, it comes under debate the necessity to make progress with the analysis of exclusion, not so much from the hegemonic position (focussed on the analysis that professionals and leading theoretical models carry out: politicians, doctors, psychologists, teachers, childminders, social workers) but from a more democratic and participative position that considers that the voice of excluded people should not only be listened while analysing exclusion processes but also in the widest processes of decision making. As stated, the main interest of this kind of research is “to give voice” and to recognise the prominent role of the people interviewed in their own story of life. In this sense, the research we are developing shares many premises with the one called Emancipatory Research (Oliver, 1992,Walmsley, 2001; Mercer, 2002, Barnes, 2001)4. b) The individual dimension of empowerment, the development of a better vital self-understanding, of exploration of the roots of our own actions. Such biographical reflectivity may turn into active knowledge, may became a platform for action. It is the idea of “acting with words” from Chamberlayne (2004). At this point it should be emphasized that social order is not only something that is transmitted, such as it has been studied from the most classical approaches in sociology , but also something which is experimented, suffered or enjoyed, something to which people react (what sometimes generates changes in the social order itself). This experiential dimension of social stratification is what matters to us in this research. Some data with regard the methodological design of the research Thus, the research we propose can be summarised in the following aspects related to the sample, the techniques of data collection and the analysis of the results. The total sample of cases of young people interviewed reaches the number of 30, distributed as follows: University Cantabria Students from group 4women economical and 4 men of University of Sevilla Total 4women 4men 16 (8 women/8men) 4 Oliver (1992) described this kind of research countering it with the models used up to then, that he called positivist and interpretative . He stated then that “disabled people have come to see research as a violation of their experience, as irrelevant to their needs and as a failing to improve their material circumstances and quality of life “(Oliver, 1992). This makes the emancipatory research to be considered as a radical alternative to the classical positivist research finding itself committed to the social change and the “empowerment”. Its strength as a research method has been such that some people have identified emancipatory research as the only suitable one to be considered inclusive (Walmsley, 2001). As Barnes (2001) described it, the emancipatory research deals with the systematic demythologisation of the structures and processes originated by disability and the establishment of a constructive dialogue between the researchers and disabled people with the aim of making the “empowerment “ of these people easier. For this reason, researchers must learn to put their knowledge and abilities at the disposal of people with disabilities. social exclusion Students from group ethnical and cultural exclusion Students from group disabling exclusion Total 4women 4 men 4women 4 men 16 (8 women/8men) 4women 4women 16 4 men 4 men (8 women/8men) 24 24 48 (12 women/12 men) (12 women/12 men) (24 women/24men) The research consist of two stages: In the first stage the young people taking part in the research provide us with their experiences through four biographical-narrative techniques: self-introduction, biographical interview, picture technique and line of life (biograma). The self-introduction is a short description the person interviewed gives of him/herself. It must be taken as an assumption, a personal option that tries to meet a consistent vision these people have about themselves. In it, the different selfs are projected - the wished self, the real one, the realised one, the expected one etc.-and some dimensions will appear that will guide the understanding of the person and his/her actions. The biographical interview is an strategy that allows us to reflect and remember episodes of one’s life. It is where the person tells things about his/her biography (personal , scholar, familiar, relationships) within the frame of an open exchange of information with the interviewer. The people interviewed are encouraged to the reconstruction of their own lives through a set of thematic issues (school experience, facilities and difficulties found along it, current familiar life, future familiar life, etc) that constitute their lives. The focusing interview follows the previous technique. In it, another conversation, once the previous technique has been deeply reviewed, is held once again with the aim of clarifying the issues which were not clear enough at the first stage (the appraisal of a certain episode, time and space where the facts took place, the event or episode itself). The analysis of a picture chosen by the interviewed him/herself allows to talk about one or various issues pointed out by them as interesting in their lives (that’s why they choose a certain picture but any other one). It also allows them to reflect on their wishes and vital expectations. The biograma brings together a collection of chronological events considered as specially significant for a proper understanding of the life of the subject. It is a graphical structure that includes spaces and times which, from the current perspective of the interviewed have kept configuring his/her life together with the current appraisal of each of them. In a second stage we expect the participants to became co-researchers of their own life. For this to be carried out, they are asked to decide themselves the ways and the people who may provide us more knowledge on their own life. Thus, they decide new techniques (based on the word or image of persons, institutions and significant places for them) that make part of their own “book of life”. Naturally, this second part is likely to be very heterogeneous according to the methods and formats in which the information is presented, but it is at the same time the most in keeping one with the individual tastes of each person. At the same time at this stage, the subjects undertake a main role in the research abandoning the passive role they played in traditional research. All as a whole makes a wide heritage of information that is structured through thematic, interpretative, and chronological coding. This coding allows us to carry out a double analysis: individual analysis (Life History of each participant) and comparative analysis among groups. Thus, firstly, we obtain an individual report of each case in which the main barriers and aids towards inclusion experimented by the students are stated. This individual report is an authentic life history to which original information with regard to their own lives is added and decided by the participants themselves. Subsequently, we will do comparative analysis that affect the self-introductions, biogramas (lines of life) , analysis of the redundancies in the scholar and social barriers, as well as in the aids for inclusion. Bibliography Biklen, D. (2000) “Constructing inclusion: lessons from critical, disability narratives” J. Inclusive Education, 4 (4), pp. 337-353. Barnes, C. (2001) ““Emancipatory” disability research: project or process?” Barnes, C. and Mercer, G. (1997) Doing disability research. Leeds, The disability press Barton, L. (2000) “Insider perspectives, citizenship and the question of critical engagement”, en Moore, M. Insider perspectives. Sheffield. Philip Armstrong Publications. Bolívar et al. (2001) La investigación biográfico-narrativa en educación. Madrid. La Muralla. Bruner, J y Weiser, S. (1995) “La invención del yo: la autobiografía y sus formas” , en D.R. Olson y N. Torrance (Comps) Cultura escrita y oralidad. Barcelona. Gedisa, pp.177-202. Chamberlayne, P. (2004) “Biographical methods and social policy in European perspective”, en Chamberlayne, P. et al. (eds) Biographical methods and professional practice. Bristol. The Policy Press. Pp. 19-37. Farrell, P. (2000). “The impact of research on developments in inclusive education”. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 4(2), 153-162. French, S. and Swain, J. (2000) “Personal perspectives on the experience of exclusion”, in M. Moore (ed.) Insider perspectives on inclusion, Sheffield, Ph. Armstrong Pub., pp 18-35 Mercer, G. (2002) “Emancipatory disability research”, en Barnes, C. ; Oliver, M. and Barton, L. (Eds). Disability studies today. Oxford, Polity, pp. 228-249. Morin, E. (1995) Introducción al pensamiento complejo. Gedisa. Morin, E. (2003) http://perso.club-internet.fr/nicol/ciret/bulletin/b12/b12c1.htm Oliver, M. (1992). “Changing the social relations of research productions?”, Disability, Handicap and Society, 7 (2), 101-114 Parrilla, A. (2002). “Acerca del origen y sentido de la educación inclusiva”, en Revista de Educación, 327, pp.11-30. Shevlin, M. and Rose, R. (eds) (2003) Encouraging voices. Dublin, National Disability Authority. Slee, R. (1997) “Supporting an international interdisciplinary research conversation”, International Journal of Inclusive Education, 1(1), i-iv. Susinos, T. (2002) “Un recorrido por la inclusión educativa española. Investigaciones y experiencias más recientes” en Revista de Educación, 327, pp.49-68. Tezanos, J.F. (2001b) La sociedad dividida. Madrid. Biblioteca Nueva. Tezanos, J.F. (Ed.) (2001a) Tendencias en desigualdad y exclusión social. Madrid. Ed. Sistema. Walmsley, J. (2001) “Normalisation, emancipatory research and inclusive research in learning disability”, Disability and Society, 16 (2), pp. 187-205. Young, I.M. (2000) La justicia y la política de la diferencia. Madrid. Ediciones Cátedra Feminismos. Zarb, G. (1997) “Researching disabling barriers” en Barnes, C. y Mercer, G. Doing disability research. Leeds, The disability press, pp.49-66.