Konstantin Stanislavski

advertisement

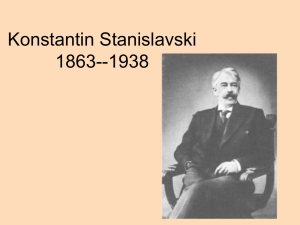

NAT IONAL QUALIFICAT IONS CURRICULUM SUPPORT Drama Twentieth-Century Theatre: Konstantin Stanislavski Annotated Bibliography [ADVANCED HIGHER] Elizabeth Cooper Charles Barron IN T RO D UC T IO N First published 2000 Electronic version 2001 © Learning and Teaching Scotland 2000 This publication may be reproduced in whole or in part for educational purposes by educational establishments in Scotland provided that no profit accrues at any stage. Acknowledgement Learning and Teaching Scotland gratefully acknowledge this contribution to the Higher Still support programme for Drama. ISBN 1 85955 878 X Learning and Teaching Scotland Gardyne Road Dundee DD5 1NY w w w .LTS co t la n d.co m HIST O RY 3 CONTENTS Introduction 1 Section 1: Recommended sources 3 Section 2: Background sources 9 Section 3: Playtexts 13 Section 4: Websites 15 DR AM A iii IN T RO D UC T IO N HIST O RY 5 INTRODUCTION Introduction Konstantin Stanislavski (1863–1938) Born in 1863 into one of the wealthiest families in Russia, Konstantin Sergeievich Alexeiev would eventually take the stage name of Stanislavski and become one of the twentieth century’s most famous theatre practitioners. In order to begin your study of this practitioner it is important to consider the context. Theatre in Russia developed at the start of the nineteenth century, heavily censored and under police control. By the end of the nineteenth century when Stanislavski became involved in professional theatre, it was in a very disorganised state. Actors would declaim lines out-front centre-stage, without reacting to other actors. There was no attempt to provide appropriate designs for each production. Sets and furniture would be drawn from stock and placed on stage wherever convenient. Costumes were f requently unrealistic, often just what the actor himself could provide. Theatre discipline was poor. Actors felt no need to be punctual, well-organised, or sober. These were all factors Stanislavski wished to challenge and change, and he devoted his life t o this work. He was influenced by the Meininger company and their radical production style. In 1897 he co-founded the Moscow Art Theatre with Nemirovich -Danchenko, acting in and directing new plays by Anton Chekhov. There he developed the practice of extensive pre-production preparation and rehearsal. For over thirty years he worked on theories to develop a ‘system’ for actors, aiming to allow them a route in to achieving the truth of feeling and authenticity for a part. He tried to eliminate over -acting clichés, stereotyped characterisation and mannerisms. He spent his life searching for a perfect acting technique and often revised and rejected ideas he had previously considered correct. Stanislavski gave the actor the means to build upon his own physical and mental resources in order to create a credible human being on stage. Stanislavski’s system was used and adapted by the American actor and director, Lee Strasberg, to develop the style of acting which became known as ‘Method’ and which is still in evidence today. DR AM A 1 2 DR AM A RE CO M M END E D S O U RC E S SECTION 1 Bentley, E, The Brecht Commentaries, New York: Grove Press, 1987 Although this book is primarily a resource for the study of Bertolt Brecht, the chapter on his stagecraft (pages 56–71) provides useful comparisons between Stanislavski’s work and Brecht’s. Cole, Toby (ed.), Acting: A Handbook of the Stanislavski Method. Introduction by Lee Strasberg, New York: Crown Publishers, 1955 This book is similar in approach to Moore’s An Actor’s Training but has the advantage of containing extracts from Stanislavski himself. It concentrates on providing information on acting techniques and on that old Stanislavski favourite – the actor’s responsibility in preparing for a role. It also contains practical exercises for the actor. Pages 130–138 This chapter is an account by Stanislavski of his production of Othello. Act 1 Scene 1 is discussed in great detail. Gives an insight into Stanislavski’s use of extensive commentaries to help the actor understand his part and think himself into it. Stanislavski expected the actor to believe that he ‘became’ the character he was playing so that his reactions would be instinctive. Pages 151–166 This is an account of the rehearsals for Gogol’s Dead Souls, directed by Stanislavski in 1932. A first-hand account by one of the actors in the Moscow Art Theatre, it describes the rehearsal techniques used, the questions put to actors and points about interpretation made by Stanislavski. Cooper, Simon and Mackey, Sally, Theatre Studies: An Approach for Advanced Level, Cheltenham: Stanley Thornes, 1995 Pages 218–225 These pages give a detailed chronology and brief biography of Stanislavski. Pages 226–239 This chapter covers the theory and practice of stage production, with particular emphasis on Realism and Naturalism. The easy-to-follow text has important points highlighted. Activities to develop practical work are set out clearly. Pages 230–233 These pages describe three occasions when Stanislavski interrupted rehearsals in order to evaluate his work. His self-analysis had a significant effect on his subsequent directing. Generally, though, he met his actors for DR AM A 3 RE CO M M END E D S O U RC E S the first rehearsal with his whole production planned in detail. As an actor, he prepared his part equally thoroughly, making copious note s on his script about interpretation, motivation, gestures and vocal variation. (Fortunately, he was usually his own director when he acted. Otherwise, the collision between the actor and the director, each with firmly set ideas on the interpretation of the role, would have been spectacular.) Pages 239–242 This section deals with some of the influences on Stanislavski, including: Mikhail Shchepkin: acknowledged as one of Russia’s greatest actors, he was born a serf and his career only really took off af ter sympathetic theatrical friends purchased his freedom from his master. He believed passionately in a realistic approach to characterisation, based on careful observation of how people behave in real life. His autobiography was one of the sources for our knowledge about Stanislavski’s work. Nikolai Gogol: writer and dramatist. He argued in favour of supporting a native Russian drama, rather than relying upon imported classics. Stanislavski dramatised his novel Dead Souls and directed it at the Moscow Art Theatre in 1932. The Meiningen Company: famous for detailed, realistic productions and a powerful influence not only on Stanislavski but on André Antoine who was introducing theatrical naturalism in France at the same time. Anton Chekhov: playwright and founder member of the Moscow Art Theatre. Jacques Dalcroze: in L’Oeuvre d’Art Vivant he expounded (at great length) his theory that all art must be based upon rhythm. Nothing must be left to the inspiration of the moment but the actor must control the shape of his body, his movements and his gestures, relating them all exactly to the lines of the setting so that he and the set become fused into a complete, rhythmic pattern. He decreed that the stage lighting must be constantly varied to match the rhythms of the actors’ movements. Taken to extremes, as they sometimes were in the early decades of the twentieth century, these ideas could lead to actors being treated as mere puppets, allowed to contribute nothing to the play’s interpretation. Although attra cted by the idea of rhythm, Stanislavski rejected Dalcroze’s more extreme views. Hartnoll, Phyllis (ed.), The Oxford Companion to the Theatre, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1972 Pages 123–124 A brief account of the life of Anton Chekhov, and his wor ks. The influence of the Moscow Art Theatre is emphasised. Without the subtlety and 4 DR AM A RE CO M M END E D S O U RC E S sensitivity of the acting style being developed there, the quality of Chekhov’s plays would not have been recognised. Pages 523–524 A description of the Meiningen Players, a company which greatly influenced the Moscow Art Theatre and Stanislavski. Their style included a new emphasis on design and on using varying stage levels. They insisted on historically correct costumes. They made the crowd an important part of the drama, and this in turn demanded a highly disciplined control of stage movement. Because they toured all over Europe and into Russia their influence was very widespread. Stanislavski recognised that their success was due to the leadership of one man, their founder, the Duke of SaxeMeiningen, and this inspired him to set himself up as a firm, even dictatorial, stage director. Pages 545–546 Information on the founding and the development of the Moscow Art Theatre. Its success in overcoming early suspicion and establishing itself as the leading centre of naturalistic theatre was remarkable. It even survived the Communist Revolution, unlike most other cultural institutions associated with the previous regime. A world tour in the 1920s spread the Stanislavski influence throughout Europe and, crucially, into America. Pages 769–770 A concise breakdown of Stanislavski’s life, education, training and influences. It lists important productions and traces some of the changes which he brought about in both acting and production styles. Hartnoll, Phyllis, A Concise History of the Theatre, London: Thames and Hudson, 1968 Chapter 11 ‘Ibsen, Chekhov and the Theatre of Ideas’ This is a very readable chapter that puts Stanislavski into context alongside such names as Ibsen, Strindberg and Shaw. The author probably leans the wrong way in deciding whether Chekhov was more important to Stanislavski than vice versa. Contemporary photographs are helpful in showing the development of staging and costume. To some extent the unnatural poses of the actors are an indication of the acting style. The photographs illustrating this chapter are excellent, particularly those on page 222 (a scene from the Moscow Art Theatre production of The Lower Depths, by Maxim Gorki, directed by Stanislavski in 1902) and page 224 (the Moscow Art Theatre Company listening to Chekhov reading his play The Seagull, which they presented in 1899. The photograph DR AM A 5 RE CO M M END E D S O U RC E S includes Stanislavski who was to play Trigorin and Nemirovich Danchenko who had co-founded the Theatre with Stanislavski the previous year.) Chapter 12 Pages 244–245 A useful account of the development of the role of the director in twentieth-century theatre. Stanislavski was primarily an actor and it was his ideas on creating a character that were most influential on later generations. However, in order to put his ideas into practice, he had to take on a kind of executive function as well. This in turn helped to establish the role of director in European and American theatre. Moore, Sonia, The Stanislavski System: The Professional Training of An Actor: Digested from the Teachings of Konstantin Stanislavski, Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1984 (second edition) This book dates from the time when Stanislavski’s methods were developing a new following, mostly because of the work of acting coaches in America. The internal, naturalistic realisation of character works well in cinema and appealed to Hollywood actors who regarded their acting as more important than their celebrity. (They were lucky. The ‘M ethod’ acquired cult status and soon they had both kudos and fame.) The book considers Stanislavski’s methods from the point of view of acting in the 1960s, analysing their underlying philosophy and suggesting more modern exercises and improvisations for students to try. Stanislavski, Konstantin, An Actor Prepares, London: Methuen, 1996 This is a seminal work, written in 1926. Its influence on modern theatre can hardly be exaggerated. The book covers in great detail the various ways in which an actor can explore a role through an inner imaginative process. There are practical exercises, based on the work which Stanislavski did with his fellow actors during the intensive preparation period. (He would refuse to announce the opening date for a play until he felt the rehearsal period had achieved the best possible results.) An Actor Prepares provides the most detailed source of information on the inner technique. Interestingly, initially Stanislavski had wished to publish it together with Building a Character which describes the actor’s work on the body. This is because he regarded his system as a psycho -physical one in which the mind and body were closely intertwined. However, for practical reasons, such as the sheer size of the proposed volume, he reluctantly abandoned this plan and agreed to two separate books. An Actor Prepares, with its emphasis on the psychological side of acting, was the first book to be published in translation in America, and had a 6 DR AM A RE CO M M END E D S O U RC E S considerable impact on the development of the Act ors Studio in New York and consequently on ‘Method’ acting. Creating a Role is a compilation of incomplete manuscripts that deal with the actor’s work on the texts. The exercises include: • the ‘magic if’. The actor must ask himself ‘What would I, the c haracter I am portraying, do if these circumstances were real?’ • asking the ‘given circumstances’: who? what? where? when? and why? to build up the detail of a social, physical and emotional character profile • discovering motivation for the character’s a ctions • breaking the play into a series of ‘units’ and analysing the objectives of each unit in detail • drawing on personal experience, recalling past emotions and memories of traumatic moments. Stanislavski believed that if the actor sought parallels between his own experience and that of the character he would have a better, a more instinctive, understanding of his role • visualising the ‘fourth wall’ between the stage and the auditorium • concentrating on the release of physical and vocal tension throu gh relaxation techniques. The book also examines theories about the subconscious since, Stanislavski argues, a character’s motivation and behaviour can only be fully understood when the workings of his subconscious are taken into account. Stanislavski died on the eve of the Russian publication of this book. Stanislavski, Konstantin, Building a Character, London: Methuen, 1996 Stanislavski died before completing this book which was compiled after his death from his manuscripts, prompt copies and rehearsal diaries. It continues on from An Actor Prepares, following the same set of ‘students’ through the process of realising a character particularly by the use of physical skills – voice and movement. The exercises include: • exploring ways of making the body fully expressive • finding motivation to energise appropriate character movement • being aware of personal gestures and characteristics which could detract from character gesture • developing vocal exercises and techniques for intonation, vocal expression and speech rhythm. Stanislavski, Konstantin, My Life in Art, New York: Theatre Arts Books, 1974 This is the most autobiographical of Stanislavski’s own works, published as early as 1924. It establishes the basis of his theories of drama, laying down DR AM A 7 RE CO M M END E D S O U RC E S criteria for judging the effectiveness of techniques used by actors for preparing a part. Because he is able to draw on experience as both an actor and a director, Stanislavski can see the processes from within as well as without. Toporkov, Vasily Osipovich (trans. Christine Edwards), Stanislavski in Rehearsal, London: Routledge, 1998 Toporkov was an actor who worked with Stanislavski in the later years of the latter’s life. He gives a clear view of what it was like to be trained by Stanislavski, analysing the techniques from the point of view of the professional actor. He was clearly in awe of the master’s constant search for better and better ways of helping the actor prepare and of his passion for constant revision. 8 DR AM A B ACK G RO U N D S O U R CE S SECTION 2 Banks, Ron and Marson, Pauline, Drama and Theatre Arts, London: Hodder and Stoughton Educational, 1998 A useful book on directing in general. Pages 296 – 300 This chapter considers how Stanislavski’s theory and practice influenced the British and American stage. Pages 335 – 338. This section considers particularly the relationship between director and actors. Benedetti, Jean, Stanislavski, His Life and Art, London: Methuen, 1999 Over the years there have been a number of biographies of Stanislavski, ranging from the respectful to the iconoclastic. Benedetti is somewhere in between, offering the facts of Stanislavski’s life as they are now established and giving a comprehensive coverage of his work. This new edition explores the collaboration and often bitter disputes with Nemirovich-Danchenko, co-founder of the Moscow Art Theatre, and traces further Stanislavski’s often troubled relationship with the company he led. It gives a new account of the difficulties and tensions that lay behind the highly influential 1922–24 American tour. Benedetti also gives us fuller versions of key moments in Stanislavski’s career: his arbitrary arrest in 1919 and his troubled relationship with the Soviet regime over artistic differences; a greater understanding of how Stanislavski’s seminal books on acting came to be written, edited and translated into English only to lead to gross misunderstanding of his work; plus the best understanding yet of the evolution of Stanislavski’s revolutionary acting ‘system’. Benedetti, Jean, Stanislavski, An Introduction, London: Methuen, 1985 Benedetti again but concentrating this time on the philosophy behind the so-called ‘system’ which Stanislavski devised as a method of creating character and which developed into something more like a life -style. Naturally, the ‘system’ changed over the years and Benedetti gives a good account of the maturing process. Braun, Edward, The Director and the Stage, London: Methuen, 1982 Ranging widely over a number of theatrical practitioners, Braun provides a careful and workman-like analysis of their strengths and their differences. DR AM A 9 B ACK G RO U N D S O U R CE S Leacroft, Richard and Helen, Theatre and Playhouse, an Illustrated Survey of Theatre Building from Ancient Greece to the Present Day , London: Methuen, 1984 What an actor or a director can do for an audi ence is always constrained by the building in which he is operating. Changing fashions in theatre design dictate changes in acting style. The declamatory style of the nineteenth-century actor was necessary because theatres were large and there was no amplification. The small, intimate off-Broadway studio theatre allows the actor to develop a naturalistic, mumbling delivery. These authors discuss such changes over the last 3,000 years. An excellent resource book for historical research. Mackey, Sally, Practical Theatre. A post-16 approach, Cheltenham: Stanley Thornes, 1997 Pages 31–32 This book looks at methods of actor training in the twentieth century and includes a very brief idiot’s guide to Stanislavski’s acting theory. It is certainly easy to read, since it is bullet pointed. It is also a useable resource for practical ideas in acting, directing and devising. Nicoll, Allardyce, The Development of the Theatre, a Study of Theatrical Art from the Beginners to the Present Day, London: Harrap & Co., 1996 Nicoll was the first of the modern theatrical historians. The broad sweep of this book makes it ideal for dipping into to check a fact or to trace a development. A useful resource, well illustrated. Pictures frequently make a point more quickly than yards of text. Theatre is a visual medium and the pictures here tell their own story of fashion changes in set and costume design. Redgrave, Michael, The Actor’s Ways and Means, London: Nick Hern Books, 1984 One of Britain’s finest actors looks at Stanislavski fr om the professional’s point of view. He shows that the Method is entirely practical, based as it is on Stanislavski’s own experience as a working actor. Moreover, he argues persuasively that it has not dated but is as useful today as it was almost 100 years ago. The 1995 edition has a new Introduction by Vanessa Redgrave. Stanislavski, Konstantin, An Actor’s Handbook, London:Vintage/Ebury, 1990 This is a handy, short paperback that distils much of Stanislavski’s thoughts about acting. It takes the form of a number of short statements that could be the basis for discussion and further exploration of Stanislavski’s ideas. It lacks the depth of his other books. 10 DR AM A B ACK G RO U N D S O U R CE S Stanislavski, Konstantin (trans. Elizabeth Reynolds Hapgood), Stanislavski on Opera, London: Routledge, 1998 Opera can be regarded as the most complete form of theatre, including as it does music and often dance as well as drama. Stanislavski regarded the elements of music and movement as crucially important in his stage work and was naturally drawn to opera. Although the demands of singing constrain some of the more physical aspects of performing in the Stanislavski Method, nonetheless many of his theories apply well to opera. In this book he writes about several operas from the point of view of applying his directorial approach to them. Naturally he writes about Russian operas – Boris Godunov and The Queen of Spades – but not exclusively. His comments on La Bohème as a piece of drama are enlightening. Strasberg, Lee, Strasberg at the Actors Studio, London: Nick Hern Books, 1984 Transcriptions of actual tuition sessions by the originator of Method Acting. The techniques have clearly undergone considerable development since Stanislavski’s time but the essence is preserved. The exercises that Strasberg devises for students at the Actors Studio in New York are hardly distinguishable from those that Stanislavski was using with the members of the Moscow Art Theatre. Also of interest Benedetti, Jean (trans.), Stanislavski and the Actor, London: Methuen Drama, 1998 Cole, Toby (ed.), Acting: A Handbook of the Stanislavski Method, 2nd edition, New York: Bonanza Books, 1955 Gorchakov, Nikolai M, Stanislavsky Directs, trans. Miriam Goldina, Westport: Greenwood Press, 1954 Jones, David Richard, Great Directors at Work. Stanislavsky, Brecht, Kazan, Brook, Berkeley: University of California Press, 1986 Mitter, Shomit, Systems of Rehearsal: Stanislavski, Brecht, Grotowski and Brook, London and New York: Routledge, 1992 Stanislavski, C, Stanislavski’s Legacy (2nd edn), (trans. E R Hapgood), London: Eyre Methuen, 1958 DR AM A 11 B ACK G RO U N D S O U R CE S Stanislavsky, Konstantin, Selected Works, (ed. Oksana Korneva), Moscow: Raduga Publishers, 1984 Stanislavsky, Konstantin, Stanislavsky on the Art of the Stage (trans. David Magarshack), London: Faber, 1967 Stanislavsky, Konstantin, Stanislavsky Produces ‘Othello’ (trans. Helen Nowak), London: Geoffrey Bles, 1948 Wiles, Timothy J, The Theater Event: Modern Theories of Performance , Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 1980 Articles Jean Benedetti, ‘A History of Stanislavski in Translation’, New Theatre Quarterly, vol. 7, no. 23, (1990), 266–278 Jean Benedetti, ‘Brecht, Stanislavski and the Art of Acting’, The Brecht Yearbook, vol. 20, 1995, 101–111 Margaret Eddershaw, ‘Brecht and Stanislavski’ etc. in Performing Brecht: Forty years of British performance, London and New York: Routledge, 1966, pp 18–25 Paul Gray, ‘Stanislavski and America: A Critical Chronology’, Tulane Drama Review, vol. 9, no. 2 (1964), 28–32 Michael Morley, ‘Brecht and Stanislavski: Polarities or Proximities?’, The Brecht Yearbook, vol. 22, 1997, 195–204 Meg Mumford, ‘Brecht Studies Stanislavski: Just a Tactical Move?’, New Theatre Quaterly, vol. 11, no. 43, 1995, 241–258 12 DR AM A PL AY T E XT S SECTION 3 Stanislavski worked on these plays either as an actor or as a director and they could be used for workshop activities based on Stanislavski’s methods. Students could find Stanislavski’s own references to the play and try to re create his approach to it. Extracts from the plays could be w ork-shopped to explore theories of acting and directing styles, or as a basis for improvisations to unlock aspects of the texts and characterisations. Chekhov, Anton, The Seagull, translation by S Mulrine, London: Nick Hern Books, 1994 The Seagull looks at the human predicament and asks what constitutes happiness, money, health and contentment. Stanislavski directed. It was his usual practice to prepare in great detail, compiling a heavily annotated prompt copy that included details of stage designs, descr iptions of setting, blocking, visualisations, movements, groupings, sound, vocal notes, rhythm, phrasing and pausing. Chekhov, Anton, Uncle Vanya, translation by S Mulrine, London: Nick Hern Books, 1994 Uncle Vanya also looks at the human predicament, thi s time through the themes of bitterness, frustration and love denied. Stanislavski directed the play and played the character of Astrov, the doctor. Chekhov, Anton, Three Sisters, translation by S Mulrine, London: Nick Hern Books, 1994 Three Sisters explores feelings about the futility of life. Stanislavski directed and gave one of his most praised performances as Vershinin. Chekhov, Anton, The Cherry Orchard, translation by S Mulrine, London: Nick Hern, 1994 The Cherry Orchard takes another look at human existence. What is it but loss, compromise and ruin? Stanislavski directed, laying particular emphasis on the psychological motivation of the characters. He took the role of Gayev. Gogol, Nikolai, The Government Inspector, introduction by S Mulrine, London: Nick Hern Books, 1994 The Government Inspector is a satire on Russian provincial life, dealing with official corruption in a small town. During the direction of this play, which Stanislavski himself dramatised from Gogol’s novel, he experimented with new rehearsal techniques, giving the actors greater responsibility for their work. He also began discussing ‘emotional memory’: actors recall a moment of deeply felt emotion in their own lives DR AM A 13 PL AY T E XT S and use the memory to recreate the feeling on stage. An act or required to show grief over the death of a close friend may not have personal experience of such an event. However, he may be able to recall his grief at the death of a pet rabbit and use that remembered emotion in his characterisation. 14 DR AM A W EB S I T ES SECTION 4 The following websites are helpful. Websites do occasionally change their names, undergo unexpected transformations and even disappear completely. These are all well established sites that are likely to remain reliable. Moscow Art Theatre www.theatre.ru/mhat/eindex.html This page is the English-language index, leading to a history of the Moscow Art Theatre, an extensive collection of historical photographs and information about Stanislavski and Danchenko. (It is a well organised site with a wealth of fascinating historical information – even more useful if you happen to read Russian.) The Official Strasberg Site www.cmgww.com/historic/strasberg This site is run by Strasberg’s estate and is very comprehensive. It is particularly useful for its coverage of hi s theories of acting and his philosophy of theatre in a number of articles written by Strasberg and interviews with him. The Actors Studio www.actors-studio.com Information on Lee Strasberg and on the history of the ‘Method’. Links to recommended books and to further sites about the Actors Studio. The Lee Strasberg Theatre Institute www.strasberg.com A detailed site about Strasberg, his theories, his teaching and the Institute. It has a list of recommended reading. The Theatre Group www.theatrgroup.com Links to The Actors Studio, Method Acting and theatres worldwide. It has a useful set of procedures which budding ‘Method’ actors can try for themselves. DR AM A 15