Education Paper - east

In this paper I wish to focus on the relationship between institutions of higher education and culture. More particularly, I want to ask what kind of culture if any ought these institutions teach. This question was central to what became known as the culture wars, and neither side of gave a very satisfactory answer. The radical side proclaimed a multiculturalism as a counter for a dead white but still oppressive identity. The conservative side favored a humanism sanctioned by the past, but with little relevance to contemporary culture. I wish to argue that contemporary colleges and universities ought to inculcate a professional ethic, the ethic of managers, lawyers, doctors, accountants, and teachers themselves.

Multiculturalism tends to see proper education as an affirmation of ethnic and gender identity, a celebration of who students are. When put in such simple terms, this is a disservice to students, who generally go to college because they wish entrance into professional culture. I believe that the function of colleges and universities today is to acculturate those students into that culture, not because that culture is necessarily superior to others, but because colleges and universities are funded in order that that culture maintain itself and attended. I would further argue that such acculturation will fact confirm the children of professionals in who they are, but will not necessarily confirm the children of the working class or children of minorities. Such young people will be transformed. A transformation of identity will necessarily involve loss, but if colleges and universities do not transform those from non-professional backgrounds, they are cheating them, robbing them of what the institutions promise.

In other words, it would be a mistake for colleges and universities to focus on diversity. Certainly it is their mission to take in a diverse student body. Certainly it is necessary to respect that student body’s origins. But the focus ought not to be on the origin but the goal, and that goal is not diversity but a unity, the unity of professional culture, which demands its own habits and virtues.

Obviously there ought to be a commitment to equity, but that commitment has to be tempered. Not all students have the same opportunities, and a basic opportunity is a pre-initiation into the culture of professionalism. Again it is not that culture of professionalism is intrinsically better than competing cultures; it is by no means the consummation of human endeavor. But it is the option most viable for most students, and not coincidentally, it is the engine the moves the academic endeavor.

On the other hand, a professional curriculum should not necessarily be all white, or all Western, or all male. After all, professional culture itself neither essentially white, or Western, or male. The movement of professional culture is to make race, national origin, and gender invisible. Professional culture would supersede those identifications.

Of course it never can. There are inevitably conflicts between the components of our identities, and the dominance of one component is generally fragile and temporary. But the tendency of professional culture is to make issues of race, gender, and sexual

orientation irrelevant, and it is not accidental that the movement towards civil equality accelerates in professional culture.

But this movement does not simply affect civil and social equality; it affects the way we imagine ourselves. The humanities as traditionally conceived fits very poorly into the professional outlook. The traditional humanities focus too much on man, on the soul (which from a professional viewpoint is an antiquated word), on what from a professional point of view are cultural trappings. From a professional perspective there is no intrinsic reason not to include writings of women and minorities. Professionals can in fact make up quotas of the kinds of writings or authors that should or should not be included, since the point of the humanities in a professional world view would not be the teaching the of the best ever written. Matthew Arnold did not subscribe to the professional ideology. Professionals, for that matter, can give lip service to the multicultural agenda, if by multiculturalism is meant cultural trappings. Professionals can allow themselves the luxury of connoisseurship on their off-hours. But professionals cannot subscribe to nonprofessional values. Whenever a conflict of values occurs, professionals must actively promote the values of their kind.

From the point of view of professional the conflict about the humanities then is not whether or not the curriculum is saturated with Dead White Males but whether or not the literary has a place in the curriculum at all. Professionalism demands many qualities, but those qualities do not include the depth or breadth of spirit. Professional life is necessarily shallow and narrow. One gives one’s life to a specialty; it is one’s expertise at that specialty that allows one to advance; and it is through this advancement that one measures success and failure. Education for such a life is vocational, although vocational can be used in a larger sense. What is called critical thinking, the ability to discern premises and consequences, the ability to identify and evaluate the logic of an argument are professionally useful. The ability to function in organizations, to cooperate, to listen and to discern tone, to criticize without alienating are useful as well. But the ability to grow spiritually by being exposed to the best in Western culture or world culture is irrelevant to the vocation of the professional. Professionals use the aesthetic to relax, and formal aesthetic training does little to aid relaxation.

Even more importantly professional life is one abstracted from roots. Life in this world focuses on the workplace not the family. Families are comparatively disposable.

Young professionals and would-be professionals live together in unsanctioned relationships before marriage; they are encouraged to marry late in life; and if their relationship is less than satisfactory, they are encouraged to divorce. Professionals spend what is euphemistically called quality time with their children. At an early age these children are sent to daycare centers. The household is rarely centered in the living room or the dining room. During a typical evening each family member is able to separate in his/her own space.

It is not that parents have suddenly become or no longer love their children. It is rather that the cultural project in which the family finds itself has changed. Parental love is frequently joined with pre-vocational ambition as professional parents seek to place their children in the best schools. Even grade school children are told about the dire career consequences of a bad report card.

In the same way professional life is anti-communal. The significant community is the workplace community. Culture is as much as anything else organizational.

Professionals have comparatively little time and comparatively little energy. They come home tired, and they often bring additional work. There is an element of classical liberal economics here. The work the professionals do creates and maintains their world, so that it would be wrong to say that their work is solely selfish. But it is not work maintains continuities or establishes rounded personal relations. The professional world is inherently superficial and a curriculum attempting to create depth is irrelevant to its demands.

If professionals are indifferent to community, they are also indifferent to the achievements or indeed the existence of the past, except as a kind of pasture in which they can relax. Reverence is not a professional virtue.

Of course one could argue that professional life as I am describing it is a monstrosity, that far from propagating it one should oppose it. Certainly it costs, costs both its practitioners and the culture at large. And it is not as if most professional

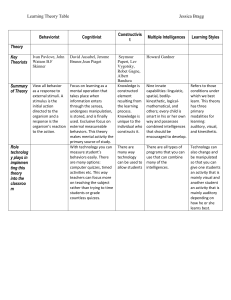

Let us take the example of intelligence. Proponents of multiculturalism argue correctly that one cannot define intelligence as if it were quality uncontaminated by cultural values. One is intelligent is specific ways, those ways are incommensurate, and both individuals and cultures choose what ways are more valuable than other ways. The very notion of intelligence implies values. But that is the point. Educators cannot avoid the notion and will inevitably value some forms of intelligence more than others whatever pieties they might feel compelled to utter when abstracted from their work.

Professionals will value the intelligence required for their line of work, and minimize the importance of other intelligences. One could argue that it is the variety in professional work and the concomitant variety of intelligences needed to perform that work that makes multiple intelligences visible in the first place. But still those intelligences necessary to specific tasks will be valued; others will not; and the hierarchy valued in intelligences will closely resemble the hierarchy in the professions themselves. And that hierarchy will finds its place in colleges and universities.