River Horses and Water Cows

advertisement

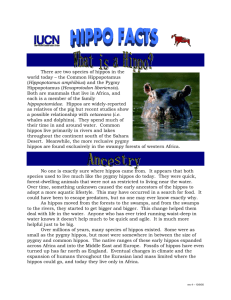

RIVER HORSES AND WATER COWS by Dr. Phillip T. Robinson University of California, San Diego Hippo History The Hippopotamuses are classified within the same scientific order (Artiodactyla) as the gazelles, deer, giraffes, and most other living hoofed mammals. Both living species of hippo, the Nile or common hippopotamus Hippopotamus amphibius and pygmy hippo Hexaprotodon (Choeropsis) liberiensis, are considered to be primitive descendants of large and clumsy prehistoric creatures that inhabited Europe, Asia, Africa, and even parts of North America. These ancestors were very pig-like in their anatomy, suggesting that hippopotamuses were derived from primitive pigs. Indeed, the pygmy hippo's previous generic designation, Choeropsis, is derived from Greek words for a "pig" (choiros) and "like" (opsis), denoting its pig-like attributes. Their modern ranges are limited to sub-Saharan Africa. The pygmy hippo was first described from several skulls sent to Dr. Samuel Morton of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia, when he was in residence in Monrovia, Liberia in 1843. The first reports from Liberian forests confused this species with the giant forest hog. The earliest whole specimens were collected for the Leiden Museum in Holland by Dr. Johann Büttikofer in the 1870s and 1880s during the first comprehensive investigations of Liberian fauna. There it is commonly called the "water cow." The common hippo was originally reported to be in the St. Paul river of Liberia, but these accounts were undoubtedly mistaken for sightings of the manatee, which in earlier days inhabited the lower navigable reaches of that river. The other anomalous report is the alleged occurrence of the pygmy hippo in Guinea Bissau, formerly Portuguese Guinea, located far west of Liberia. This 1958 report is poorly documented and thought to be attributed to the collection of a young common hippo. No collected specimens exist. The animals reported to inhabit fringing forests in Sierra Leone in 1968 are now presumed to be gone, leaving only the Gola Forest as a lost refuge. The Republic of Guinea habitat is under logging pressure and is presumed to be significantly diminishing. By contrast, the common hippopotamus was scientifically classified in 1758, but it was known well before this time. Limestone relief carvings in Egypt's sixth dynasty depict scenes including the common hippo, and hippos were exhibited in circuses during Roman times as curiosities. For most of this century no distinct subspecies of the pygmy hippo have been recognized. The common hippo has been divided into a number of subspecies over its wide range. However, in 1969, studies of stored pygmy hippo skulls, collected in the late 1930s from Nigeria by the English colonial official Heslop, were shown to be different enough from the core population to be classified as a subspecies. It is nearly impossible that this Nigerian population still survives in the Niger delta area and it is surprising that its existence was so poorly known or documented. This outlying population is of evolutionary interest, as the forest in which it occurred is naturally separated by a belt of savanna and open woodland several hundred kilometers wide from the nearest forest to the west, where all other pygmy hippo populations occur. This belt of savanna is called the "Dahomey Gap," named after Dahomey (now Benin), just west of Nigeria, through which it passes. It is zoologically important as it limits the eastward distribution of a great many West African forest species--the pygmy hippo is thus now known to be an interesting exception to this rule. Anatomy and Evolution While the common and pygmy hippos have many anatomic similarities, the differ-ences between these two species go beyond the ten-fold disparity in body weight, pygmy hippos weigh between 180-720 kg, an adult male river hippo can exceed 2,000 kg. While the Nile hippo is notably gregarious and inhabits open rivers accessible to grazing areas, the pygmy hippo is usually solitary and is confined to forested river habitats, foraging in forests and swamps. The Nile hippo has massive, compact toes which are strongly connected to each other, while the toes of the pygmy hippo are only moderately webbed, allowing the feet to spread out much more; this may help make it more mobile on land. The legs and neck of the pygmy species are proportionately longer and the head proportionately smaller than those of the Nile hippo. The body profile is sloped forward, a presumed advantage in moving through the dense vegetation of swamps and waterside. In many respects, such as their size, shape, behavior, and habitat, pygmy hippos resemble the tapir species which occur in forests in Central and South America and in the Far East. Despite their similarities, tapirs are in fact quite unrelated to hippos and are much closer to the horse and rhinoceros families; they thus form an interesting example of convergent evolution, whereby unrelated animals evolve to resemble each other through sharing similar habitats and diets. Pygmy hippos, like the Nile hippos, have specific aquatic adaptations. In pygmies the nostrils and ear openings both have strong muscular valves, although the bony orbits of the eyes are less developed than those of the larger hippo to facilitate vision while resting in water. Habits and Habitat In no areas do the ranges of the two hippo species overlap. The common hippo is widespread in Africa south of the Sahara, but in West Africa it is limited to the large rivers in savanna regions. The pygmy hippo's known range is restricted to four West African countries: Sierra Leone, Liberia, Guinea, and the Côte d'Ivoire (Ivory Coast). The greater portion of its range is in Liberia and Côte d'Ivoire, where large blocks of forest can still be found. It inhabits primarily heavily forested areas, especially stream margins and swamps where the principal tree is the Raphia palm. The geographic range has been notably reduced during the past 50 years, owing to human settlement, forest exploitation, and hunting. In addition to inhabiting large blocks of forest relatively near the West African coast, pygmy hippos formerly occurred in the narrow strips of forests fringing the rivers and streams extending into woodland and Guinea savannah areas in recent decades. These areas replace the forest as one travels farther north in the countries in its range; however, it seems likely to have been hunted out of all these by now. In the wild, the pygmy hippo's diet appears to consist exclusively of vegetable matter, including the leaves and rootstocks of a variety of semi-aquatic and forest floor herbs, as well as various fallen fruits from forest trees. Unlike most other artiodactyls, like the domestic cow, and its wild relatives, hippos are not ruminants, they do not ferment their food in their stomachs. Instead, they resemble horses in fermenting their food in the hindgut, with microbial degradation of the plant materials consumed taking place in the caecum, the first part of the large intestine, which is sizeable in this animal. This mode of digestion is usually considered an adaptation to a highly fibrous, generally "low-quality" vegetable diet. The droppings are poorly formed and similar to those of the common hippo. The pygmy hippo tends to be nocturnal. In dark and twilight hours it uses specific routes often enough to form trails on the thinly vegetated forest floor, or tunnellike paths through dense, green waterside and swamp vegetation. During the day, the animals spend considerable time in wet, lowland sites or resting in small rivers, wallows, or backwaters. Liberian hunters report encountering pygmy hippos asleep in forest wallows, occasionally allowing them to approach undetected. Secretive in their habits, pygmy hippos are seldom seen by local peoples, unlike the conspicuous presence of river hippos in other parts of Africa. In a manner similar to that of the river hippopotamus, the pygmy hippo scentmarks its trails with feces by vigorously switching its tail and scattering the debris rather widely. Hunters have always taken advantage of these trails for pit trapping hippos, particularly before the widespread availability of firearms. Pygmy hippos are hunted for their meat; they are regarded as a very desirable food species, resembling wild pig in taste and texture. No trade value is ascribed to the teeth, unlike those of its larger cousin, which are sought after as ivory, and the animal is seldom an agricultural nuisance. It is not known how far individual pygmy hippos roam in the wild, or whether they keep to well defined home ranges, but their habit of fecal marking implies they may be at least partly territorial in defending particular areas against incursions from other members of the species. During the rainy season (May-September), however, animals are reported by hunters to disperse over wide areas in the forest zone. The effects of predators on pygmy hippo populations are unknown, but the principal carnivore capable of attacking an animal this size is the leopard. The gestation period for the pygmy hippo is approximately 6.5 months, but no accurate data on the breeding season have been published for the wild population. It would appear that birth may occur at any time during the year and in captivity births have occurred in all months of the year. Females give birth to a single offspring and sexual maturity occurs at about four to five years of age. In contrast to river hippos, which readily give birth to calves in the water, land births appear to be the rule with pygmies, although young calves readily take to the water. Pygmy Folklore There are many folktales about pygmy hippos. One suggests that the pygmy finds its way through the forest at night by carrying a diamond in its mouth, which lights its path. By day the hippo is said to hide the diamond where it cannot be found. If a hunter is lucky enough to catch one at night, the belief is that the diamond can be taken. Generally, hunters view the pygmy hippo with caution, as hippos are known to be aggressive when encountered at close range, particularly if wounded. Another story frequently told by villagers is that baby pygmy hippos do not nurse, but instead lick the foamy secretions from the mother's skin for nourishment. In fact, female pygmy hippos have two somewhat inconspicuous nipples on the abdomen. The skin is well supplied with pores which exude droplets of fluid, as is also the case with its larger relative. The secretions serve to lubricate and protect the skin and make the body very slippery to the touch. With physical exertion, the lubricating layer takes on a white, foamy appearance, and secretions may be found on the foliage along paths if one of the animals has just passed there. Exposure to intense sunlight can produce solar dermatitis and skin damage in this species if it is kept from shade or water. Pygmies in Captivity The first live pygmy hippo was taken from Sierra Leone in 1873 by Mr. John Price of the British Colonial Office. The young hippo was transported by steam- ship to Dublin, Ireland, but it became sick on the voyage and was kept in the heated quarters of the ship's captain; it died shortly after arrival at the Phoenix Park Zoo. In 1911 Major Hans Schomburgk directed an expedition to Liberia to capture pygmy hippos. Using pit traps, two males and one female were caught, carried by porters and canoe to the coast and shipped to Germany. Subsequently they were sold to New York's Bronx Zoo, where they reproduced. Since this beginning pygmies have become established in numerous zoos, where they reproduce well and are relatively easy to maintain. According to the international studbook records, kept at the Basel Zoo in Switzerland, there were over 340 animals in captivity in 1991. Thanks to their relatively long lifespan (up to 42 years), the survival of the pygmy hippo in captivity seems assured. In North America, where some 70 animals reside in captivity, the studbook is kept at the Lincoln Park Zoological Gardens in Chicago, Illinois. Recent assessments indicate that captive populations are aging and that genetic enrichment will be required to maintain future diversity. Survival Prospects The long term preservation of the pygmy hippo in the wild is in jeopardy. The survival of wild populations is contingent on the establishment of large, protected forest areas. Without the securement of such areas, loss of habitat will eventually eliminate the pygmy hippo from the wild. This process is already underway with road building, intensified logging, agriculture, and mining taking place in forested areas; indeed, the rate of forest destruction in West Africa is one of the highest in the world. As this destruction proceeds, the formerly continuous forest habitats are becoming fragmented into smaller and smaller isolated patches of soThis spells impending disaster, not just for the pygmy hippo, but for many of the other forest-dwelling species of West Africa. The ecological character of these "islands" is inevitably different from that of the forest of which they were once part, and many animal and plant species will find it increasing difficult to survive in them. To preserve the forest in its whole, incredible diversity, and especially to safeguard the larger animals within it, is necessary to set aside the largest possible tracts of land. Other animals which depend on these forests are key mammal species, such as duikers, and birds, like the critically endangered white-naped picathartes or bald crow, Picathartes gymnocephalus. A vital area for the pygmy hippo's protection is the Sapo forest in eastern Liberia. A 509-square-mile block of this forest was chartered as Sapo National Park in 1983, establishing its only national park. Additional areas are under serious consideration for survey to magnify the conservation value of this fascinating and biologically rich forest environment.. Another area in which the species occurs is in the Tai National Park in western Côte d'Ivoire. Tai is now subject to poaching, agricultural encroachment and gold mining in the park's river beds. The pygmy hippo is classified in the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red Data Book as a "vulnerable" species (VU). With habitat steadily deteriorating and subdividing in the heart of its range, prompt conservation initiatives are required if this species is to survive in the wild far into the twenty-first century. Dr. Robinson conducted a field survey of the pygmy hippo for the World Wild Life Fund in Liberia and Sierra Leone in 1968. called "ecological islands.” REFERENCES Astey, S. (1991): Large mammal distribution in Liberia. (Unpubl.) rep. to W.W.F. International, Gland: 81 pp. Corbet, G. B. (1969): The taxonomic status of the Pygmy hippopotamus, Choeropsis liberiensis, from the Niger Delta. J. Zool., 1958:387-394. Cristino, J. J. de SA E.Melo. (1958): Statut des ongules en Guinee Portugaise. Mammalia, 22:387-389. Eltringham, S. K. (1996): The Pygmy Hippopotamus (Hexaprotodon liberiensis). In Pigs, Peccaries, and Hippos, W.L.R. Oliver, ed., 55-60. IUCN, Gland. Heslop, I. R. P. (1945): The pygmy hippopotamus in Nigeria. Field (Nigeria), 185: 629-630. Robinson, P.T. (1970): The status of the pygmy hippopotamus and other wildlife in West Africa. (Unpubl.) M.S. thesis, University of Michigan: 80 pp. Robinson, P.T. (1971): Wildlife Trends in Liberia and Sierra Leone.Oryx XI:2-3. 117-122. Robinson, P.T. (1981): Bibliography for the pygmy hippopotamus Choeropsis liberiensis (Morton, 1844). (Unpubl.) rep. to IUCN/SSC Hippo Specialist Group: 8 pp. Thompson, S.D, G. Wirz-Hlavacek (1996) Pygmy Hippopotamus (Hexaprotodon liberiensis). In Annual Report on Conservation & Science, 121-122. American Zoo and Aquarium Association, Wheeling, West Virginia.