Embedding ozone protection in the sustainable development agenda

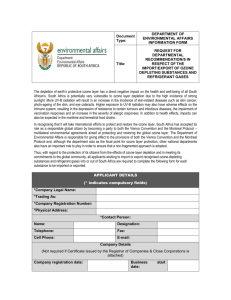

advertisement