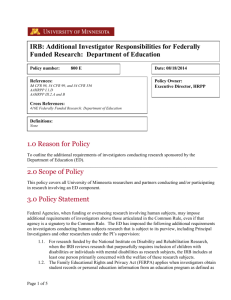

Return to Index Page - Montclair State University

advertisement