Lower Cotter Catchment - Territory and Municipal Services

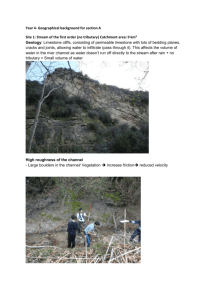

advertisement