NAACCR SUMMARY

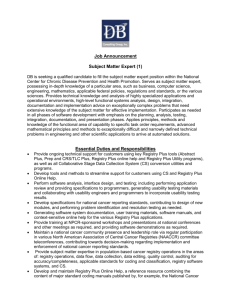

advertisement