Common Law - University of Oklahoma

advertisement

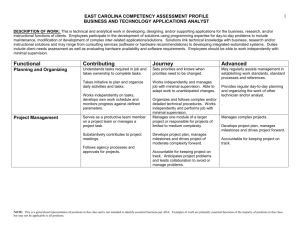

The Association Between the Legal and Financial Reporting Environments and Forecast Performance of Individual Analysts Ran Barniv Kent State University Graduate School of Management, CBA Kent, OH 44242 Phone: 330-672-1112 Fax: 330-672-2545 E-mail: rbarniv@bsa3.kent.edu Mark Myring Ball State University College of Business Muncie, IN 47306 Phone: 765-285-5108 Fax: 765-285-8024 E-mail: mmyring@bsu.edu Wayne B. Thomas* University of Oklahoma Michael F. Price College of Business 307 W. Brooks, Room 212B Norman, OK 73019 Phone: 405-325-5789 Fax: 405-325-7348 E-mail: wthomas@ou.edu * Contact author. We appreciate the helpful comments of two anonymous reviewers, Patricia O’Brien (associate editor), A. Amir, S. Beninga, workshop participants at the universities of Cincinnati, Pennsylvania State, and Tel Aviv, and participants in a concurrent session of the AAA annual meeting, Hawaii, August 2003. We also acknowledge Thomson Financial for providing I/B/E/S International and U.S. Detail History data. The Association Between the Legal and Financial Reporting Environments and Forecast Performance of Individual Analysts Abstract We test the ability of analyst characteristics to explain relative forecast accuracy across legal origins (common law versus civil law). Common law countries generally have more effective corporate governance mechanisms, including stronger investor protection laws and inputs provided through higher-quality financial reporting systems. In this type of environment, we predict that analysts with superior ability and resources in common law countries will more consistently outperform their peers because appropriate market-based incentives exist. In civil law countries, where the demand for earnings information is reduced because of weaker corporate governance mechanisms and lower-quality financial reporting, we predict that analysts with superior ability will less consistently provide superior forecasts. Results are consistent with our expectations and suggest an association between legal and financial reporting environments and analysts’ forecast behavior. Keywords Analysts’ characteristics, relative forecast performance, common law, civil law. JEL Descriptors G38, K22, M41 The Association Between the Legal and Financial Reporting Environments and Forecast Performance of Individual Analysts 1. Introduction We test the ability of analyst characteristics to explain relative forecast accuracy across legal origins. In common law countries, where investor protection laws are stronger and financial reporting is generally perceived to have higher quality (La Porta, Lopez-de-Silanes, Shleifer, and Vishny 1997, 1998, 2000a; Ball, Kothari, and Robin 2000), the increased demand by investors for earnings information may create incentives for analysts to provide that information accurately. Analysts with superior characteristics (e.g., ability, effort, experience, resources, etc.) are more likely to issue a superior forecast relative to their peers. In civil law countries, weaker investor protection laws and lower-quality financial reporting may reduce the economic incentives of analysts to incur costly activities to provide a superior earnings forecast. We expect that it will be more difficult to relate individual analysts’ characteristics to relative forecast performance in civil law countries. Examining the relation between relative forecast performance and analyst characteristics across legal regimes provides evidence outside the United States, where the bulk of this research has been conducted.1 Understanding analyst behavior in other environments provides additional insight into how analysts’ efforts in accurately forecasting earnings can contribute to the informational efficiency of financial markets (Frankel, Kothari, and Weber 2002). The results also contribute to our understanding of the relation between investors’ demands and analysts’ behavior (Defond and Hung 2002). As the value relevance of reported earnings declines, investors may have less demand for analysts’ earnings forecasts and demand other sources of information such as cash flow forecasts.2 Our results may also be helpful in investigating other related research issues, such as the value relevance of accounting numbers across countries. Prior research has focused primarily on estimating the relation between earnings and stock prices to understand investors’ demand for accounting earnings (e.g., Ball, Kothari, and Robin 2000; Ali and Hwang 2000). We extend this literature by examining whether the relation between analyst characteristics and relative forecast accuracy differs across legal origins consistent with investors’ demand for earnings information. Consistent with expectations, we find that the relation between analyst characteristics and relative forecast accuracy is stronger in common law countries. These results are consistent with analysts’ forecast behavior responding to the demand by investors for earnings information. In common law countries where investor protection laws are stronger, financial reporting is higher-quality, and the demand by investors for earnings information is greater, analysts with superior abilities tend to distinguish themselves more clearly. In civil law countries, it is more difficult to explain analysts’ relative forecast accuracy. Overall, we find that 2 the relation is strongest in the United States, followed by non-U.S. common law countries. The relation is weakest in the civil law countries. Results within the three origins of the civil law classification (French, German, and Scandinavian) suggest that the quality of financial reporting systems plays a role in these relations beyond the influence of investor protection laws. Finally, we find some empirical support for the notion that cash flow forecasts may substitute for earnings forecasts when earnings are less relevant (Defond and Hung 2002). The relation between analysts’ characteristics and relative cash flow forecast accuracy is stronger in civil law countries than in common law countries. The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 develops the hypotheses. Section 3 outlines the research design and section 4 details the data and sample selection. Section 5 reports results and section 6 provides additional analyses. The paper concludes in section 7. 2. Hypotheses We provide the following rationale for our tests. Common law countries are generally perceived to have stronger investor protection laws (La Porta, Lopez-de-Silanes, Shleifer, and Vishny 1997, 1998, 2000a)3 and higher-quality financial reporting (Ball, Kothari, and Robin 2000).4 In these settings, earnings information can play a more prominent role in corporate governance mechanisms and therefore have greater value relevance.5 The greater value relevance of 3 earnings information increases investors’ demand for that information when making decisions. The increased demand by investors offers proper economic incentives for analysts to compete in providing accurate forecasts of earnings. Those analysts having the ability and resources to outperform other analysts will, on average, do so because the market-based reward structure established by investor demand offers analysts fair incentives (Schipper 1991). In other words, the rewards for making accurate forecasts fairly outweigh the cost of gathering and processing information when investor protection laws are strong and the quality of the financial reporting system is good. For common law countries, we expect analysts with superior characteristics (ability, effort, experience, resources, etc.) to more consistently outperform their peers, resulting in a stronger relation between analysts’ characteristics and relative forecast accuracy. In civil law countries, financial accounting systems are generally perceived to be of lower quality in terms of their ability to reflect accurately the underlying economic activity of the firm (Ball, Kothari, and Robin 2000; Guenther and Young 2000; Bhattacharya, Daouk, and Welker 2003; Francis, Khurana, and Pereira 2004). Financial accounting practices in civil law countries are oriented less toward serving the needs of outside investors (O’Brien 1998; Lang, Lins, and Miller 2004) and investor protection laws are weaker (La Porta, Lopez-de-Silanes, Shleifer, and Vishny 1997, 1998, 2000a). These factors likely weaken the demand by investors for earnings information, which reduces the 4 economic incentives of superior analysts to outperform their peers. Providing a superior earnings forecast is costly and analysts with superior abilities and resources will incur the incremental costs of gathering information only when they expect to be equitably rewarded. We expect that the reduction in incentives of superior analysts to make superior forecasts will lead to a weaker relation between analyst characteristics and relative forecast performance in civil law countries (i.e., relative forecast accuracy occurs more randomly in civil law countries). Furthermore, among the common law countries, prior studies cited in the preceding paragraphs suggest that the United States has some of the strongest investor protection laws and higher-quality financial reporting. If investor protection laws and quality of financial reporting affect the relevance of accounting earnings to investors, one would expect the demand for earnings information by investors and the incentives of analysts to compete and provide that information accurately to be greater in the United States than in most of the non-U.S. common law countries. Similarly, as discussed in the preceding paragraphs, we expect that analysts in non-U.S. common law countries will have more incentive to compete and provide more accurate forecasts relative to their peers than will analysts in civil law countries. Overall, the preceding ideas lead to our first three hypotheses. 5 H1: Analyst characteristics better explain relative forecast accuracy in the common law countries than in civil law countries. H2: Analyst characteristics better explain relative forecast accuracy in the United States than in non-U.S. common law countries. H3: Analyst characteristics better explain relative forecast accuracy in non-U.S. common law countries than in civil law countries. It is also interesting to consider whether the strength of investor protection laws or the quality of the financial reporting system offers the greater motivation to analysts to provide superior forecasts. We examine whether analyst characteristics are useful for explaining relative forecast accuracy across three groups of civil law countries. Within the civil law origin, La Porta, Lopez-deSilanes, Shleifer, and Vishny (1997, 1998) find that countries of the French origin have weaker investor protection laws than do countries of the German origin. However, countries of the French origin have higher quality and more transparent financial accounting information than do countries of the German origin (Ball, Kothari, and Robin 2000; Francis, Khurana, and Pereira 2004). Thus, the incentives for analysts to provide superior forecasts might be stronger in the German origin countries because of better investor protection laws or stronger in the French origin countries because of higher-quality financial reporting. By estimating the ability of analyst characteristics to explain relative forecast accuracy in the French versus German origins, we expect to obtain some 6 indication of the impact that investor protection laws, on the one hand, versus quality of financial reporting, on the other hand, has on the behavior of analysts. Relative to other civil law origin countries, the Scandinavian origin has the better investor protection laws (La Porta, Lopez-de-Silanes, Shleifer, and Vishny 1997, 1998) and the higher-quality financial reporting (Ball, Kothari, and Robin 2000; Francis, Khurana, and Pereira 2004). We therefore predict that analyst characteristics will have greater explanatory power for this group of civil law countries. Thus, H4: Analyst characteristics differentially explain the relative forecast accuracy across the three civil law origins. Table 1 summarizes the strength of investor protection laws and the quality and transparency of financial reporting and their expected impact on the relative performance of analysts across legal origins. 3. Research design and determinants of relative forecast accuracy Extending the model of Jacob, Lys, and Neale (1999), we examine the impact of analyst activity, experience, portfolio complexity, specialization, and internal environmental factors on the ability of analysts to produce superior forecasts of earnings relative to their peers. One possible limitation of using their model is that it was developed in a U.S. context. While there could be other important analyst characteristics in other countries, we believe the United States 7 provides a good setting for establishing a benchmark model of the way in which analyst characteristics explain relative forecast accuracy when the demand for earnings information is high.6 We estimate the following model, where the first ten variables are those used in Jacob, Lys, and Neale (1999) and the final three represent additional international attributes of analysts and their brokerage firms. (AFEk,j,t/MAFEj,t)-1 = 0 + 1*HORIZk,j,t + 2*CHANGEk,j,t + 3*EXPk,j,t + 4*COMPk,j,t + 5*SPECk,j,t + 6*FREQk,j,t + 7*B-SIZEk,j,t + 8*B-INDk,j,t + 9*PINk,j,t + 10*POUTk,j,t + 11*C-EXPk,j,t + 12*C-SPECk,j,t + 13*B-Ck,j,t + k,j,t The dependent variable measures the relative forecast accuracy of analyst k to all other analysts following company j in year t. AFE is the absolute value of analyst k’s forecast error and MAFE is the mean absolute forecast error of all analysts issuing a forecast for company j in year t.7 The independent variables are defined as follows: HORIZ = The number of calendar days between the forecast issue date and the earnings announcement date. CHANGE = Dummy variable that takes a value of 1 (0 otherwise) when there has been a change in the assignment of specific analyst k following company j for a particular brokerage in year t.8 EXP = The natural log of the number of years analyst k has issued forecasts for company j. COMP = The number of companies followed by analyst k in the calendar year in which the forecast was issued. SPEC = Percentage of companies followed by analyst k with the same I/B/E/S industry code as company j. FREQ = Number of forecasts issued by analyst k for company j in year t. 8 B-SIZE = Percentile ranking of the total number of analysts employed by the brokerage house to which analyst k belongs in the calendar year in which the forecast was issued, relative to other brokerage houses. B-IND = Percentage of analyst k’s brokerage house analysts which follows company j’s industry in the calendar year in which the forecast was issued. PIN = Portion of new analysts that come from outside the brokerage house relative to the total number of analysts who worked for analysts k’s brokerage house during the calendar year in which the forecast was issued. POUT = Portion of analysts who left analyst k’s brokerage house relative to the total number of analysts who worked for analysts k’s brokerage house during the calendar year in which the forecast was issued. C-EXP = Dummy variable that takes a value of 1 (0 otherwise) when analyst k has issued forecasts for more than three years for any company in a country.9 C-SPEC = Percentage of companies followed by analyst k in the same country where the analyst has issued forecasts for company j in year t. B-C = Percentage of analyst k’s brokerage house analysts which follow company j’s country in the calendar year in which the forecast was issued. The variables HORIZ and FREQ represent analyst activity, EXP and CEXP stand for experience, COMP represents portfolio complexity, while SPEC and C-SPEC correspond to specialization. Finally, internal environmental factors include B-SIZE, B-IND, B-C, PIN, and POUT. Consistent with prior research, we subtract the mean of the independent variable for each year for the empirical tests (Clement 1999; Jacob, Lys, and Neale 1999). For the common law sample, we expect HORIZ, COMP, PIN, and POUT to have a positive relation with relative forecast error and CHANGE, EXP, SPEC, FREQ, B-SIZE, B-IND, C-EXP, CSPEC, and B-C to have a negative relation. We expect the significance of the relations to be higher for the U.S. sample than for the non-U.S. common law 9 sample. For our civil law sample, we predict that the significance of the relations will be further reduced or become insignificant. 4. Data and sample selection The data are obtained from I/B/E/S for the period 1984-2001 (for companies with fiscal year-end between January 1984 and December 2000). We use the International edition and U.S. edition of the I/B/E/S Detail History files.10 Summary statistics for the final sample used in our study are reported in Table 2. The results are aggregated for 12 common law countries and 21 civil law countries. We base our aggregation of the results on legal origins (La Porta, Lopez-de-Silanes, Shleifer, and Vishny 1997, 1998, 2000a). The common law countries are further separated into the United States and non-U.S. common law countries.11 We further classify the civil law countries into French origin (11), German origin (6), and Scandinavian origin (4). Including only the analyst’s most recent annual forecast for each company-year, the database includes 1,038,329 annual earnings forecasts issued by 30,966 analysts for 27,379 companies. We first exclude observations for countries not included in our data, that are team forecasts, and that do not have actual annual earnings available. This reduces the sample to 28,738 analysts in 1,321 brokerage firms who provide 1,012,189 company-year forecasts for 25,933 10 companies in the 33 countries. We further exclude observations where there are less than three analysts following the company in that year.12 Panel A of Table 2 reports summary statistics for the final sample. The final sample consists of 673,817 annual forecasts for 15,220 companies, issued by 27,082 analysts who work for 1,151 brokerage houses. The majority of forecasts (79%) were for companies in common law countries.13 The average number of analyst following per firm-year is greatest in the U.S. (10.55), followed by nonU.S. common law countries (8.65) and civil law countries (8.23).14 Panel B of Table 2 shows additional descriptive statistics regarding firm characteristics for each of the legal regimes. For our sample, we report that civil law companies are, on average, larger than common law companies. This is important because an overweighting of larger firms in the common law sample could bias results in favor of our hypotheses. The enhanced information environment of larger firms increases demand for their securities (Merton 1987), offering greater economic incentives to superior analysts to outperform their peers. In this case, civil law countries (i.e., larger firms in our study) rather than common law countries would be expected to exhibit a stronger association between relative forecast accuracy and analyst characteristics, absent any effects of the legal origin (e.g., investor protection laws, quality of accounting). We also show that the common law firms have higher earnings to price ratio and greater analyst forecast errors than the civil law firms. Forecast dispersion among analysts is approximately the same across 11 origins. We further report descriptive statistics for U.S. versus non-US companies and for companies in the three civil law origins. 5. Results Univariate statistics Table 3 shows the means and medians for variables representing analyst characteristics for each legal origin. The reported unadjusted amounts provide descriptive statistics for the independent variables and comparisons between (1) common law and civil law countries, (2) the U.S. and non-U.S. common law countries, (3) non-U.S. common law countries and civil law countries, and (4) pairs of the three civil law origin countries.15 In general, the common law analysts provide significantly shorter forecast horizons, present fewer changes in analysts following a company, have more experience, follow fewer companies, specialize more in the same industry, and provide more forecasts for each company than do the analysts in the civil law countries. They are employed in larger brokerage houses with larger percentages of analysts following companies in the same industry, and these houses have smaller portions of new and outgoing analysts than do civil law analysts. Finally, common law analysts have more countryspecific experience, greater specialization in a particular country, and greater brokerage house specialization within a country.16 12 Further analyses of the descriptive statistics show significant differences between all characteristics of analysts in the United States and analysts in nonU.S. common law countries. For example, U.S. analysts have more experience and follow more companies in the same industry, but they provide fewer forecasts for each company than analysts in the non-U.S. common law countries. Similarly, all characteristics of analysts in the non-U.S. common law countries differ significantly from those of the civil law countries. For instance, analysts in the civil law countries are less experienced, have less country-specific experience, provide less forecasts for each company, and have a greater forecast horizon. Finally, the comparisons between the three civil law origin countries show significant t-statistics and Wilcoxon Z-statistics for all of the 13 independent variables. Test of hypothesis 1 Table 4 presents OLS results for the common law countries and the civil law countries.17 Eleven coefficients are statistically significant in the predicted direction for the common law sample, but only six coefficients are significant in the predicted direction for the civil law sample. The coefficients for the forecast horizon (HORIZ) and the analyst-broker turnover variables (PIN and POUT) are positive (as predicted) and they are significant in the common law and the civil law countries. The estimated coefficient for portfolio complexity (COMP) is 13 positive and statistically significant for the common law countries, suggesting that the larger number of companies followed by an analyst reduces forecast accuracy. This coefficient is not significant for the civil law countries. The coefficients for frequency (FREQ) are significant and negative (as predicted) for both origins. The coefficients for analyst specialization (SPEC), broker size (B-SIZE), and brokerindustry specialization (B-IND) are significantly negative (as predicted) for the common law countries, while the coefficients for B-SIZE and SPEC are not significant (at p <0.05) and B-IND is significant in the unpredicted direction for the civil law countries. These results suggest that internal environment factors in brokerage houses in civil law countries do not have the predicted impact on analysts’ relative forecast accuracy as they do in common law countries. The regression coefficients for experience (EXP) are not statistically significant across the two groups of countries. The coefficients for the three international variables are statistically significant for the common law countries. The coefficients for C-SPEC and B-C are significantly negative (as predicted) for both origins. The coefficient for CEXP, however, is significantly positive (not negative as predicted) for the common law origin and insignificant for the civil law origin. This result indicates that analysts in common law countries may have reasons to extend their forecasting activity to other countries (e.g., they may possess private knowledge) and this extension leads to more accurate forecasting in the first couple of years. 14 The R2 for common law countries is 0.1491 and the R2 for civil law countries is 0.0811, suggesting that analyst characteristics better explain relative forecast accuracy in the common law countries than in civil law countries. The Chow test (F = 237.6) suggests that model coefficients are significantly different across origins.18 The t-statistics for tests of differences in individual coefficients are also reported in Table 4.19 The results show that portfolio complexity, specialization, analyst activity, and internal environment factors, but not experience, more significantly explain (in the predicted directions) analysts’ relative forecast accuracy in the common law countries than in the civil law countries. Eight of the estimated coefficients in the common law countries have significantly greater magnitudes, in the predicted directions, than do the corresponding coefficients in the civil law countries. For example, relative forecast accuracy increases by 0.37 percent per day as the forecast age decreases in the common law countries, which is significantly faster (t = 36.3) than the 0.23 percent increase per day in the civil law countries, controlling for other variables in the model. This result suggests that common law analysts provide more effort and compete more aggressively in utilizing recent information than do civil law analysts. The relative forecast accuracy increases by 3.97 percent for each additional forecast issued by analysts (FREQ) in the common law countries, which is significantly greater (t = 4.97) than the 1.56 percent increase in relative forecast accuracy in the civil law countries. The differences in the coefficients are 15 not significant for the three international variables. This result suggests that domestic characteristics have a greater impact on the relative forecast accuracy in the common law countries than in the civil law countries, but the international characteristics provide similar effects on the relative forecast accuracy in both origins. In sum, the empirical evidence supports our first hypothesis that analyst characteristics better explain the relative forecast accuracy in common law countries than in civil law countries. It seems that analysts in common law countries compete to provide superior forecasts more than do analysts in civil law countries, and those analysts with superior abilities and resources tend to outperform their peers. Test of hypothesis 2 Table 4 also reports the results for comparing the regression model between the United States and non-U.S. common law countries. In the United States, ten coefficients are statistically significant in the predicted direction. One coefficient (C-EXP) is significant in the unpredicted direction.20 Eight coefficients are significant in the predicted directions for the non-U.S. common law countries. The coefficient for COMP is significant in the unpredicted direction. The R2s are 0.1494 for the United States and 0.1271 for the non-U.S. common law countries and the Chow test of differences in model coefficients is 16 significant (F = 75.5).21 Furthermore, of the ten coefficients significant in the predicted direction for the United States, eight have a significantly greater magnitude than the corresponding coefficients for the non-U.S. common law sample. For example, the magnitude of the coefficient for B-SIZE is three times greater for the U.S. sample than for the non-U.S. common law sample (t = –4.70). The coefficients for international specialization (C-SPEC) and brokercountry factor (B-C) are significantly negative (as predicted). The coefficient for B-C is significantly more negative for the United States than for the non-U.S. common law countries (t = –4.09). The coefficients for C-SPEC, however, are not significantly different. The coefficient for country-specific experience (CEXP) is significantly positive (not negative as predicted) for the United States, and it is not significantly different from the coefficient for the non-U.S. common law countries. In sum, our results support the second hypothesis. In non-U.S. common law countries, where investor protection laws and financial reporting are somewhat weaker than in the United States, we find less evidence that superior analysts distinguish themselves. Test of hypothesis 3 On the final right column of Table 4, we report results for comparing the regression model between the non-U.S. common law countries and the civil law countries. The R2 for the non-U.S. common law countries (0.1271) is greater than 17 that of the civil law countries (0.0811). The significant Chow test (F = 76.0) suggests that model coefficients are not equal across origins. Four of the variables have a significantly greater magnitude with the predicted signs for the non-U.S. common law countries than for the civil law countries. The estimated coefficient for B-C is the only one that is more significant in the civil law countries. Overall, the results support the third hypothesis, indicating that analyst characteristics have less ability to distinguish superior analysts in the civil law countries than in the non-U.S. common law countries. The results in Table 4 support the first three hypotheses. We conclude that analyst characteristics better explain relative forecast accuracy in countries with stronger investor protection laws and higher-quality financial reporting. In the United States, where investor protection laws and financial reporting are generally considered the strongest, we find the most evidence that analyst characteristics distinguish superior analysts. Furthermore, the evidence is stronger for non-U.S. common law countries than for civil law countries. Test of hypothesis 4 Analyses within the civil law countries provide an interesting setting to test the relative influence of investor protection laws and the quality of financial reporting systems. Compared to German origin countries, those of French origin 18 have weaker investor protection laws (La Porta, Lopez-de-Silanes, Shleifer, and Vishny 1997) but higher-quality financial reporting (Ball, Kothari, and Robin 2000; Francis, Khurana, and Pereira 2004). Which environment provides superior analysts with stronger incentives to distinguish themselves? If analyst forecast behavior is related more to quality of financial reporting (strength of investor protection laws), we would then expect superior analysts to distinguish themselves better in French (German) origin countries. Therefore, tests within French and German origin classifications provide some insights into the relative influence investor protection laws and quality of financial reporting can have on investors’ demand for earnings information and analysts’ forecast activities. Since Scandinavian countries have stronger investor protection laws and higher-quality financial reporting systems (relative to other civil law countries), we expect this group to provide the strongest evidence of analysts’ differential forecast ability. Table 5 reports regression results by the three civil law origins. The R2s are 0.0980, 0.0881, and 0.0711, respectively, for countries of the Scandinavian, French, and Germanic origins. Chow tests are significant, suggesting differences in model coefficients across origins. Six (five) regression coefficients are significant for French (German) origin countries in the predicted direction.22 Of the six significant coefficients for the French sample, three have a significantly greater magnitude in the predicted direction than those for the German sample. For example, the estimated positive coefficient for HORIZ in the French origin 19 countries is significantly greater than the positive coefficient in the German origin countries (t = 8.29). In addition, the negative coefficient for EXP (as predicted, but significant only at p < 0.10) for the French sample is significantly smaller than the significant positive coefficient for the German sample (t = –3.76). The greater explanatory power for the Scandinavian sample provides evidence consistent with analyst behavior being affected by the strength of investor protection laws and quality of financial reporting. Five coefficients are significant in the predicted direction and three (two) of these have significantly larger magnitudes in the predicted directions than those reported for the French (German) sample. The differences between the estimated coefficient of all other variables in the Scandinavian origin and the other two origins are not significant. None of the coefficients for the Scandinavian sample is significant in the unpredicted direction, whereas two coefficients are significant in the unpredicted direction for the French and German countries. We do not consider coefficients in the unpredicted direction to constitute evidence consistent with analysts responding to investors’ demands for more accurate forecasts. We base the analyst characteristics used in the model on a reasonable understanding of the factors likely to distinguish superior analysts. These variables have received empirical support in the literature. Therefore, the significance of the analyst characteristics in the predicted direction provides a basis upon which to evaluate 20 the forecast behavior of analysts in different legal and financial reporting environments. In summary, within the civil law countries, the greatest and most consistent evidence that superior analysts distinguish themselves comes from the Scandinavian origin countries, which have higher-quality financial reporting and stronger investor protection laws. Countries with stronger investor protection laws but lower-quality financial reporting (i.e., German origin) show the weakest evidence that analysts strive to outperform their peers. The evidence for the countries with higher-quality financial reporting but weak investor protection laws (i.e., French origin) appears to be somewhere in the middle. The differences in the impact of analyst characteristics on relative forecast accuracy across the civil law countries suggest that while investor protection laws can influence analyst behavior, they are not the only factors affecting relative forecast accuracy. The quality, timeliness, and transparency of financial reporting systems certainly play a role in the demand for earnings information and the incentives of analysts to distinguish themselves from their peers. These results support the view of Bushman and Smith (2001) that financial accounting information is an important input to corporate control mechanism. 6. Additional analyses Impact of analyst characteristics on the relative accuracy of cash flow forecasts 21 Cash flow forecasts may substitute for earnings forecasts in countries where earnings forecasts are less value-relevant to investors (Defond and Hung 2002). Hung (2000) reports that accruals reduce the value relevance of earnings in countries with weak shareholder protection (civil law countries), but not in countries with strong shareholder protection (common law countries). The reduced relevance of accruals in civil law countries likely decreases the relevance of earnings information to investors and increases the relevance of cash flow information. As investor demand for information moves from earnings to cash flows, analysts may spend relatively more time and resources on forecasting cash flows. If this is so, then analyst characteristics may better explain relative cash flow forecast accuracy in civil law countries. We provide an analysis of cash flow relative forecast accuracy using the same methodology used for earnings forecasts. We modify some relevant independent variables (e.g., horizon, experience, frequency, and country-specific experience) for cash flow forecasts. The other independent variables are the same as those used for the earnings analyses. The untabulated results show greater explanatory power for the 13variable regression in the civil law countries than in the common law countries. The R2s are 0.146 for the civil law countries and 0.075 for the common law countries. The Chow test is significant (F = 117.7). The explanatory powers are approximately the same for the United States and the non-U.S. common law 22 countries. These findings provide some support for the alternate conjecture that some analysts in civil law countries may spend more time and resources on forecasting cash flow than on earnings, as those with superior characteristics tend to more consistently outperform their peers. Again, these results are consistent with analysts responding to investors’ demand for information.23 Forecast performance and termination We test whether analysts are less likely to continue forecasting when their performance is bad. We select the worst analyst (i.e., the one with the greatest forecast error) for each firm-year and estimate the probability that the analyst will forecast earnings for that same company in the following year. We find that 54.1 percent of the worst analysts from civil law countries provide forecasts for the same firm next year. Only 34.8 percent and 41.0 percent of the worst analysts continue to forecast for the same firm in the following year for the United States and non-U.S. common law countries, respectively. The percentages of worst analysts that continue to forecast for the same firm are similar across the civil law groups of countries. These results are consistent with the analyst forecast environment being more competitive in common law countries. Analysts that provide bad forecasts and therefore fail to meet the information demands of investors are less likely to continue forecasting earnings for these firms. 23 7. Summary and conclusions In this study, we test the ability of analyst characteristics to explain relative forecast accuracy across legal origins (common law versus civil law). Common law countries typically have higher-quality financial reporting systems and stronger investor protection laws. In this type of environment, the increased demand by investors for earnings information increases the economic incentives of analysts to provide accurate earnings forecasts. We expect analysts with superior characteristics (e.g., ability, effort, experience, resources, etc.) to outperform their peers in common law countries. In civil law countries, the demand for earnings information is reduced because of weaker investor protection laws and lower-quality financial reporting. The reduced demand by investors for earnings information reduces the incentives for analysts to provide accurate forecasts. Superior analysts may not be motivated to provide more accurate forecasts if they have no expectation of being equitably rewarded for their efforts and costs. Thus, we expect the relative performance of individual analysts to be less systematic, making the relation between analyst characteristics and relative forecast accuracy weaker in civil law countries. We find results consistent with analyst behavior being related to legal origins. In common law countries, analyst characteristics better explain relative forecast accuracy. Analyst characteristics show the weakest association with relative forecast accuracy in civil law countries. The strongest evidence that 24 superior analysts have incentives to outperform their peers comes from the United States, where investor protection laws are arguably more effective and where financial reporting has higher quality. The evidence of superior analysts outperforming their peers in non-U.S. common law countries is greater than that in civil law countries but less than that in the United States. Additional sensitivity analyses support these conclusions and provide further insights into the impact of legal origin on financial analysts’ activities. We also examine the relation between relative forecast performance and analyst characteristics within the civil law countries. Those of French origin have higher-quality financial reporting systems, while those of German origin have stronger investor protection laws. The Scandinavian origin countries have higherquality financial reporting and stronger investor protection laws relative to other civil law countries. The evidence most consistent with superior analysts outperforming their peers comes from the Scandinavian origin countries, followed by the French origin countries. German origin countries provide the least consistent evidence that analysts actively compete to outperform their peers. These results constitute initial evidence that quality of financial reporting plays an incremental and perhaps larger role in affecting analysts’ forecast behavior and investors’ demand for earnings information than does the strength of investor protection laws. 25 Future research can further understand the impact that legal origin and financial reporting quality have on investors’ demand for earnings information and analysts’ activities by considering additional analyst characteristics. In our paper, we use a model developed in a U.S. context and incorporate some “international” variables. While the U.S. environment is a natural starting point for a model relating investor demand for earnings information to analysts’ activities, this represents a possible limitation of the study. Other variables in other countries may lead to additional insights in this area. Another potential for future research would be to consider how differences in information asymmetry across countries affects the incentives of superior analysts to outperform other analysts. One might expect superior analysts to have greater incentives when information asymmetry is high because the gains to exploiting accurate forecasts may be highest under such situations. However, this expectation would need to be reconciled to the findings presented in this paper that superior analysts better distinguish themselves in common law countries, where information asymmetry is generally perceived to be lower. 26 Endnotes: 1 Early studies on the relative forecast accuracy of individual analysts revealed no systematic differences in abilities (e.g., O’Brien 1987; Coggin and Hunter 1989; O’Brien 1990; Butler and Lang 1991). More recent research has, however, found some differences (e.g., see Stickel 1992; Sinha, Brown, and Das 1997). Subsequent research has sought to explain these differences (Mikhail, Walther, and Willis 1997; Clement 1999; Jacob, Lys, and Neale 1999). In an international context, Rees, Swanson, and Clement (2003) associate forecast accuracy with cultural factors in several countries. 2 Francis, Schipper, and Vincent (2002) find a complementary, rather then substitutional, relation between earnings announcements and analyst reports. Similarly, we assume that the roles of financial accounting systems and analyst activities are complements rather than substitutes. Analysts provide forecasts of earnings based on mandatory GAAP in each country, and forecasting lower-quality earnings cannot substitute for reporting lower-quality earnings. 3 Research shows that greater legal protection is associated with more valuable stock markets and a larger number of listed firms (La Porta, Lopez-de-Silanes, Shleifer, and Vishny 1997), larger listed firms (Kumar, Rajan, and Zingales1999), greater cross-listing of foreign companies (Pagano, Randl, Roell, and Zechner 2001), higher valuations for listed firms (Claessens, Djankov, Fan, and Lang 1999; La Porta, Lopez-de-Silanes, Shleifer, and Vishny 1999a), greater dividend payouts (La Porta, Lopez-de-Silanes, Shleifer, and Vishny 2000b), lower concentration of ownership and control (La Porta, Lopez-de-Silanes, Shleifer, and Vishny 1999b; Claessens, Djankov, and Lang 2000), lower private benefits of control (Zingales 1994; Nenova 1999), and higher correlation between investment opportunities and actual investments (Wurgler 2000). Prior findings on investor protection and equity markets have also received some theoretical support (Shleifer and Wolfenzon 2000). 4 The development of financial markets is directly related to the quality of financial accounting information (Black 2001). Countries with more developed financial markets have better accounting disclosures (Levine 2001; Hope 2003a, b, c), more timely and transparent accounting information (Ali and Hwang 2000; Ball, Kothari, and Robin 2000; Guenther and Young 2000), less management of reported earnings (Leuz, Nanda, and Wysocki 2003; Bhattacharya, Daouk, and Welker 2003; Fulkerson, Jackson, and Meek 2002), higher-quality earnings (Hung 2000; Fulkerson, Jackson, and Meek 2002), and greater demand for auditing services (Francis, Khurana, and Pereira 2004). 5 Bushman and Smith (2001) suggest that the corporate control mechanisms can include both internal mechanisms (e.g., managerial incentive plans) and external mechanisms (e.g., monitoring by outside shareholders or debtholders and securities laws that protect outside investors against expropriation by corporate insiders). Financial accounting systems provide direct and indirect inputs into corporate control mechanisms. 6 In the United States, the high demand by investors for earnings information has lead to strong competition among analysts to forecast that information accurately. In civil law countries, the relation between analyst behavior and the usefulness of financial accounting information is less obvious (O’Brien 1998). As the demand for future earnings information weakens, analysts have fewer economic incentives to outperform their peers and characteristics identified by the benchmark model should have less ability to explain relative forecast accuracy. 7 We do not focus on whether consensus analyst forecast errors differ across legal regimes. Analysts’ forecast errors can be affected by a number of factors including economic and cultural conditions, income smoothing, industry composition, earnings management, management of analysts’ forecasts, or level of economic development (Basu, Hwang, and Jan 1998). Our 27 within-firm design allows us to identify whether analysts with superior abilities and resources reliably outperform their peers, while controlling for these potentially confounding effects. 8 The variable CHANGE refers neither to a change in the overall number of analysts following a firm nor to a change in number of analyst following in a particular brokerage firm. CHANGE refers to our firm-year-analyst observations and takes the value one in the first year t when particular analyst k is assigned or replaced by the brokerage firm for forecasting earnings for firm j. 9 We use a cut off of three years because it is about the 75th percentile of analysts in most countries. We assume that the highest quartile could be considered as experienced analysts in a country. We also measure C-EXP as a continuous variable consistent with EXP, but the two variables are highly correlated. 10 On a global scale, I/B/E/S currently receives forecasts from more than 7,000 analysts representing 800 brokerage firms providing forecasts for approximately 18,000 companies. Many analysts in our database who provided forecasts in previous years are currently inactive. 11 Results for the United States are reported separately for testing the second hypothesis and for two other reasons. First, U.S. observations make up approximately 58 percent of our global sample. Second, reporting separate results for the U.S. sample facilitates comparisons with prior U.S. studies (Jacob, Lys, and Neale 1999; Clement 1999). 12 Similar to Jacob, Lys, and Neale (1999) and Clement (1999), we require at least three analysts so that our measure of relative forecast performance is meaningful. 13 Less than ten percent of the analysts provide forecasts for firms in more than one country. Observations are classified into legal origin based on firm location rather than analyst location. As a sensitivity test, we control for differences in sample sizes by randomly selecting observations from the full common law sample, the U.S. sample, and the non-U.S. common law sample so that all samples sizes would equal the number of observations for the civil law sample. The results for the random samples resemble those for the complete samples reported in Table 4, suggesting that differences in sample size do not confound the results. 14 Presumably, as the incentives of analysts to follow a firm increase, more analysts will follow the firm and forecast accuracy will increase (Alford and Berger 1999). We calculate the correlations (1) between forecast accuracy and number of analysts and (2) between the change in EPS and the change in the number of analysts following the firm. We find these correlations are stronger for the United States and non-U.S. common law countries than for civil law countries. These results provide additional support for the notion that the incentives of individual analyst to forecast more accurately are stronger in common law countries. 15 While we use the mean-adjusted amounts in the regression analyses, we report unadjusted raw amounts for each descriptive statistic for the independent variables since subtracting the annual means from each independent variable produces means equal to zero. 16 I/B/E/S history is longer for the United States than for non-U.S. countries. We re-estimate the results for the sub-periods 1991-2001 and 1995-2001. These more recent samples minimize the effect of analysts with reported one or two years of experience in the first or second year of available data. Univariate and OLS results for these subperiods are very similar to those reported in Tables 3 and 4, respectively. 17 We also examine the model including year-intercept dummies that are not statistically significant for the regressions reported in Tables 4 and 5. Therefore, these results are not reported. 18 The Chow F-test (Greene 2003) is used to test whether some or all the regression coefficients are equal between the common law and civil law origins. 28 19 The reported t-statistics examine the significance of the difference in slope coefficients between the civil law and common law regressions. We do not report an alternative presentation of pooling the observations and using interactive binary variables to test the differences between the estimated coefficients of the two samples (Kennedy, 1992, pp. 220-225). These results are not reported for two reasons. First, the t-tests for the differences in coefficients reported in Table 4 and 5 are the same using either method. Thus, results of testing the incremental significance of the interactions and the method reported in our paper are econometrically equivalent. Second, the R2s for each sample would not be available using the pooled model with interactive binary variables. 20 We also compare our results with Jacob, Lys, and Neale (1999) using their ten-variable OLS regression model. Our untabulated results in the United States resemble theirs. We report greater explanatory power than them and we obtain significant estimated coefficients for CHANGE and PIN and insignificant coefficient for EXP. We interpret these findings as results of using more recent data for 1984-2001 (Jacob, Lys, and Neale used 1981-1992), using annual data -quarterly data are not available for countries other than the United States (they used quarterly data), and employing I/B/E/S data (while they use Zack’s database). Our results are similar to findings reported by Clement (1999) who uses I/B/E/S U.S. annual data for 1985-1994 and reports adjusted R2s closer to ours, even though four of his seven variables differ from Jacob, Lys, and Neale. 21 We also examine results for Canada using 28,437 analyst-company-year observations. The results (not tabulated) show that the R2 and most estimated coefficients resemble those of the non-U.S. common law countries rather those reported for the United States. 22 The coefficients for B-IND are significantly positive (not negative as predicted) for the French and the German origin countries. This result suggests that industry specialization in the brokerage house increases the relative forecast error rather than decreases it, unlike in the United States. Contrary to the predictions, analyst experience (EXP) increases relative forecast error in the German origin countries, and increasing the number of companies followed (COMP) decreases relative forecast error in the French origin countries. 23 The results should be interpreted with caution since our final cash flow sample includes only 49,654 analyst-firm-year observations with complete data for all variables. Analysts’ cash flow coverage is very limited in the United States (Defond and Hung 2002). Our cash flow sample size is less than 1% of the U.S. earnings sample, about 15% of the non-U.S. common law earnings sample, and about 19% of the civil law earnings sample. We report results after winsorizing relative cash flow forecast accuracy at the 1st and 99th percentiles. 29 References Alford, A., and P. Berger. 1999. A simultaneous equations analysis of forecast accuracy, analyst following, and trading volume. Journal of Accounting, Auditing & Finance 14 (3): 219-240. Ali, A., and L. Hwang. 2000. Country-specific factors related to financial reporting and the value relevance of accounting data. Journal of Accounting Research 38 (1): 1-21. Ball, R., S. Kothari, and A. Robin. 2000. The effect of international instructional factors on properties of accounting earnings. Journal of Accounting and Economics 29 (1): 1-51. Basu, S., L. Hwang, and C-L. Jan. 1998. International valuation in accounting measurement rules and analysts’ earnings forecast errors. Journal of Business Finance & Accountings 25 (9/10): 1207-1241. Bhattacharya, U., H. Daouk, and M. Welker. 2003. The world price of earnings opacity. The Accounting Review 78 (3): 641-678. Black, B. 2001. The legal and institutional preconditions for strong securities markets. UCLA Law Review 48 (4): 781-858. Bushman, R., and A. Smith. 2001. Financial accounting information and corporate governance. Journal of Accounting and Economics 32 (2): 237333. Butler, K., and L. Lang. 1991. The forecast accuracy of individual analysts: evidence of systematic optimism and pessimism. Journal of Accounting Research 29 (1): 150-156. Claessens, S., S. Djankov, and L. Lang. 2000. The separation of ownership and control in east asian corporations. Journal of Financial Economics 58 (1/2): 81-112. Claessens, S., S. Djankov, J. Fan, and L. Lang. 1999. Expropriation of minority shareholders in East Asia. Working paper at The World Bank: Washington D.C.. Clement, M. 1999. Analyst forecast accuracy: Do ability, resources, and portfolio complexity matter? Journal of Accounting and Economics 27 (3): 285303. Coggin, D., and J. Hunter. 1989. Analysts forecast of EPS growth decomposition of error, relative accuracy and relation to return. Working paper at Michigan State University. 30 DeFond, M., and M. Hung. 2002. International institutional factors and analysts’ cash flow forecasts. Working paper at University of Southern California. Francis, J., I. Khurana, and R. Pereira. 2004. The role of accounting and auditing in corporate governance and the development of financial markets around the world. Asia-Pacific Journal of Accounting & Economics (Forthcoming). Francis, J., K. Schipper, and L. Vincent. 2002. Earnings announcements and competing information. Journal of Accounting and Economics 33 (3): 313-342. Frankel, R., S. P. Kothari, and J. Weber. 2002. Determinants of the informativeness of analyst research. Working paper at Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Fulkerson, C., S. Jackson, and G. Meek. 2002. International institutional factors and earnings management. Working paper at University of Texas at San Antonio and Oklahoma State University. Greene, W. H. 2003. Econometric Analysis. Fifth Ed., Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. Guenther, D. and D. Young. 2000. The association between financial accounting measures and real economic activity: A multinational study. Journal of Accounting and Economics 29 (1): 53-72. Hope, O.-K. 2003a. Disclosure practices, enforcement of accounting standards, and analysts’ forecast accuracy: An international study. Journal of Accounting Research 41 (2): 235-272. Hope, O.-K. 2003b. Accounting policy disclosures and analysts’ forecasts. Contemporary Accounting Research 20 (2): 295-321. Hope, O.-K. 2003c. Firm-level disclosures and the relative roles of culture and legal origin. Journal of International Financial Management and Accounting 14 (1): 218-248. Hung, M. 2000. Accounting standards and value relevance of financial statements: an international analysis. Journal of Accounting and Economics 30 (3): 401-420. Jacob, J., T. Lys, and M. Neale. 1999. Expertise in forecasting performance of security analysts. Journal of Accounting and Economics 28 (1): 51-82. Jaffe, L. 1992. The 1992 International Accounting Databook. Dublin: Lafferty Publications Ltd.. Kennedy, P. 1992. A Guide to Econometrics. Cambridge: MIT Press. 31 Kumar, K., R. Rajan, and L. Zingales. 1999. What determines firm size? NBER Working Paper 7208. National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA. Lang, M.H. K.V. Lins, and D.P. Miller. 2004. Concentrated control, analyst following and valuation: Do analysts matter most when investors are protected least? Journal of Accounting Research 42 (3): 589-623. La Porta, R., F. Lopez-de-Silanes, A. Shleifer, and R. Vishny. 1997. Legal determinants of external finance. Journal of Finance 52 (3): 1131-1150. La Porta, R., F. Lopez-de-Silanes, A. Shleifer, and R. Vishny. 1998. Law and finance. Journal of Political Economy 106 (6): 1113-1155. La Porta, R., F. Lopez-de-Silanes, A. Shleifer, and R. Vishny. 1999a. Corporate ownership around the world. Journal of Finance 54: 471-517. La Porta, R., F. Lopez-de-Silanes, A. Shleifer, and R. Vishny. 1999b. Investor protection and corporate valuation. NBER Working Paper 7403. National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA. La Porta, R., F. Lopez-de-Silanes, A. Shleifer, and R. Vishny. 2000a. Investor protection and corporate governance. Journal of Financial Economics 58 (1/2): 3-27. La Porta, R., F. Lopez-de-Silanes, A. Shleifer, and R. Vishny. 2000b. Agency problems and dividend policies around the world. Journal of Finance 54 (1): 1-33. Leuz, C., D. Nanda, and P. Wysocki. 2003. Investor protection and earnings management: An international comparison. Journal of Financial Economics 69 (3): 505-527. Levine, R. 2001. Napoleon, Burses, and Growth: With a Focus on Latin America in Market Augmenting Government. Omar Azfar and Charles Caldwell eds. Merton, R. 1987. Presidential address: A simple model of capital market equilibrium with incomplete information. Journal of Finance 42: 483-510. Mikhail, M., B. Walther, and R. Willis. 1997. Do security analyst improve their performance with experience? Journal of Accounting Research 35 (Supplement): 131-166. Nenova, T. 1999. The value of a corporate vote and private benefits: A crosscountry analysis. Working paper at Harvard University: Cambridge, MA. O’Brien, P. 1987. Individual forecasting ability. Managerial Finance 13 (2): 3-9. 32 O’Brien, P. 1990. Forecast accuracy of individual analysts in nine industries. Journal of Accounting Research 28 (2): 286-304. O’Brien, P. 1998. Discussion of ‘International variation in accounting measurement rules and analysts’ earnings forecast errors.’ Journal of Business Finance and Accounting 25 (4): 1249-1254. Pagano, M., O. Randl, A. Roell, and J. Zechner. 2001. What makes stock exchanges succeed? Evidence from cross-listing decisions. European Economic Review 45 (4-6): 770-782. Rees, L., E. Swanson, and M. Clement. 2003. The influence of corporate governance, culture, and income predictability on the characteristics that distinguish superior analysts. Journal of Accounting, Auditing and Finance 18 (4): 593-618. Schipper, K. 1991. Analysts’ forecast. Accounting Horizons 5 (4): 105-121. Shleifer, A., and D. Wolfenzon. 2000. Investor protection and equity markets. Working paper at Harvard University and New York University. Sinha, P., L. Brown, and S. Das. 1997. A Re-examination of financial analysts’ differential earnings forecast accuracy. Contemporary Accounting Research 14 (1): 1-42. Stickel, S. 1992. Reputation and performance among security analysts. Journal of Finance 47 (5): 1811-1836. Wurgler, J. 2000. Financial markets and the allocation of capital. Journal of Financial Economics 58 (1/2): 187-214. Zingales, L. 1994. The value of the voting eight: A study of the Milan Stock Exchange. The Review of Financial Studies 7 (1): 125-148. 33 TABLE 1 Investor protection laws, quality and transparency of financial reporting, and their expected impact on the ability of analyst characteristics to explain relative forecast accuracy Expected Impact on Relative Forecasts Quality and Transparency of Accuracy Origin Investor Protection Laws Financial Reporting Efficiency Antidirector Creditor of Judicial Accrual Disclosure Audit Rightsa Rightsa Systemb Indexc Indexd Spendinge Common Law f Stronger 4.0 3.11 8.15 Higher 0.76 70.6 0.27 Greater Civil Lawg Average 2.4 1.83 7.39 Average 0.58 65.1 0.14 Less United States Non-U.S. Common Frenchh Germani Scandinavianj Strongest Stronger 5.0 3.9 1.00 3.23 10.0 8.04 Highest Higher 0.86 0.74 71.0 70.5 0.24 0.27 Greatest Greater Weaker Average Above Avg. 2.3 2.3 3.0 1.58 2.33 2.00 6.56 8.54 10.0 Average Below Avg. Higher 0.64 0.43 0.63 62.1 62.7 74.0 0.12 0.12 0.22 Below average Below average Average Numbers reported represent mean amounts obtained from the following studies: a La Porta, Lopez-de-Silanes, Shleifer, and Vishny (1998) – higher number indicates more rights, creditor rights may be classified separately. b La Porta, Lopez-de-Silanes, Shleifer, and Vishny (1998) – higher number indicates more efficiency. c Hung (2000) – higher number indicates greater use of accruals. d Francis, Khurana, and Pereira (2004) – higher number indicates better disclosure. e Jaffe (1992) as reported in Francis, Khurana, and Pereira (2004) – higher number indicates more audit spending. f Countries in the common law origin are Australia, Canada, Hong Kong, India, Ireland, Malaysia, New Zealand, Singapore, South Africa, Thailand, United Kingdom, and United States. g Countries in the civil law origin are Argentina, Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Indonesia, Italy, Japan, South Korea, Mexico, Netherlands, Norway, Philippines, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Taiwan, and Turkey. h Countries in the French origin are Argentina, Belgium, France, Indonesia, Italy, Mexico, Netherlands, Philippines, Portugal, Spain, and Turkey. i Countries in the German origin are Austria, Germany, Japan, South Korea, Switzerland, and Taiwan. j Countries in the Scandinavian origin are Denmark, Finland, Norway, and Sweden. 34 TABLE 2 I/B/E/S summary statistics for our sample, sample period 1984-2001. Panel A: Number of analysts and forecasts across legal origins Number of Analystsa Legal Origin Common law Origind Civil law Origine Final Observations Used Number of Firm-Year Forecastsb Number of Firm yearsc Average Number of Analysts Following 18,009 9,073 27,082 535,462 138,355 673,817 53,785 16,806 70,591 9.96 8.23 US Non-U.S. common law Origin 9,198 8,811 390,121 145,341 36,985 16,800 10.55 8.66 French Originf German Origing Scandinavian Originh 4,735 3,129 1,209 70,011 52,951 15,393 7,488 7,469 1,849 9.35 7.09 8.33 Panel B: Firm characteristics across legal origins. Common Law Origin Civil Law Origin U.S. Non-U.S. Common Law Origin MVE Mean(Med) 1004.10 (444.61) 1199.18 (643.13) 1060.78 (486.33) 879.38 (365.57) EPS/PRICE Mean(Med) 0.0905 (0.061) 0.0487 (0.005) 0.0318 (0.0554) 0.2209 (0.0814) SD(CON)/PRICE Mean(Med) 0.0168 (0.002) 0.0177 (0.001) 0.0043 (0.0010) 0.0446 (0.0094) AFE/PRICE Mean(Med) 0.0706 (0.1620) 0.0310 (0.001) 0.0666 (0.0430) 0.0795 (0.2188) 0.0873 (0.0134) 0.0131 (0.0034) 0.0360 (0.0530) 0.0305 (0.0028) 0.0042 (0.0004) 0.0205 (0.0082) 0.0565 (0.0022) 0.0076 (0.0006) 0.0301 (0.0068) 18.1* 77.3* -1.8 9.7* 27.9* 122.6* -79.5* -62.9* -89.0* -133.0* -8.7* -78.7* French Origin 965.15 (419.17) German Origin 1540.25 (1102.75) Scandinavian Origin 786.78 (378.32) Common-Law Origin versus Civil-Law Origin t-statastic -18.7* Wilcoxon -18.9* U.S. versus non-U.S. Common-Law Origin t-statastic 17.0* Wilcoxon 17.0* (Table 2 continued on the next page) 35 TABLE 2 (continued) I/B/E/S summary statistics for our sample, sample period 1984-2001. Panel B (continued): Firm characteristics across legal origins. Non-U.S. Common-Law Origin versus Civil-Law Origin t-statastic -25.3* 25.3* Wilcoxon -25.2* 84.6* French Origin versus German Origin t-statastic -28.8* 20.5* Wilcoxon -33.6* 20.4* French Origin versus Scandinavian Origin t-statastic 6.2* 7.1* Wilcoxon 1.3 -13.0* German Origin versus Scandinavian Origin t-statastic 23.9* -8.8* Wilcoxon 25.2* -35.4* a 52.1* 80.9* 24.1* 65.8* 27.4* 26.6* 21.0* 24.2* 5.1* -21.3* 5.6* -15.4* -24.4* -46.6* -13.7* -38.0* The number of analysts includes all analysts that provide at least one forecast for one company during the period. Many analysts provide forecasts for many companies. b Only the most recent forecast is included in the reported number of firm-year forecasts. c We report only forecasts for companies followed by at least three analysts. d Common law countries are Australia, Canada, Hong Kong, India, Ireland, Malaysia, New Zealand, Singapore, South Africa, Thailand, United Kingdom, and United States. e Civil law countries are Argentina, Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Indonesia, Italy, Japan, South Korea, Mexico, Netherlands, Norway, Philippines, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Taiwan, and Turkey. f Countries in the French origin are Argentina, Belgium, France, Indonesia, Italy, Mexico, Netherlands, Philippines, Portugal, Spain, and Turkey. g Countries in the German origin are Austria, Germany, Japan, South Korea, Switzerland, and Taiwan. h Countries in the Scandinavian origin are Denmark, Finland, Norway, and Sweden. MVE = Market value of equity in million U.S. dollars. EPS/PRICE = EPS deflated by price (including negative EPS). SD(CON)/PRICE = Standard deviation of I/B/E/S consensus deflated by price. AFE/PRICE = Absolute forecast error deflated by price. 36 TABLE 3 Raw univariate statistics: Means (medians) by origin, sample period: 1984-2001a Panel A: Common law origin, civil law origin, United States, and non-U.S. common law origin. U.S. vs. Non-U.S. Non-U.S. Common Non-U.S Common Common Civil Common vs. Civil common vs. Civil Law Law United Law t-stat. t- stat. t-stat. b c d e e Variables Origin Origin States Origin (Z- stat.) (Z- stat.) (Z-stat.)e HORIZ 123.3 134.6 124.1 121.3 -38.3 * 9.44* -31.9* (95.0) (111.0) (95.0) (93.0) (-27.6) * (23.8)* (-29.8)* CHANGE 0.20 0.21 0.24 0.19 -4.90 * 12.5* -11.4* (0.00) (0.00) (0.00) (0.00) (-4.93) * (12.4)* (-11.4)* EXP 0.80 0.59 0.84 0.71 106.1 * 58.3* 48.6* (0.69) (0.69) (0.69) (0.69) (88.6) * (48.5)* (45.6)* COMP 25.2 26.2 22.3 32.9 -9.17 * -85.6* 36.2* (17.0) (14.0) (18.0) (16.0) (90.7) * (30.4)* (47.7)* SPEC 0.67 0.51 0.71 0.58 174.2 * 133.7* 51.8* (0.80) (0.50) (0.85) (0.64) (166.3) * (141.9)* (48.9)* FREQ 3.56 2.96 3.11 4.78 65.6 * -113.0* 104.2* (3.00) (2.00) (3.00) (3.00) (67.4) * (-39.6)* (82.2)* B-SIZE 0.87 0.84 0.88 0.87 68.9 * 20.0* 18.7* (0.94) (0.90) (0.94) (0.91) (67.4) * (48.1)* (10.6)* B-IND 0.13 0.12 0.14 0.10 28.5 * 127.0* -41.1* (0.09) (0.09) (0.10) (0.08) (8.23) * (90.6)* (-32.0)* PIN 0.29 0.38 0.27 0.33 -133.2 * -88.5* -46.0* (0.25) (0.33) (0.24) (0.27) (-136.7) * (-69.2)* (-52.4)* POUT 0.25 0.29 0.24 0.29 -65.9 * -81.7* -6.16* (0.21) (0.24) (0.20) (0.23) (-61.6) * (-75.4)* (-9.20)* C-EXP 0.56 0.31 0.61 0.42 177.5 * 170.5* 61.4* (1.00) (0.00) (1.00) (0.00) (167.0) * (166.9)* (60.9)* C-SPEC 0.93 0.78 0.98 0.79 113.4 * 224.1* 6.30* (1.00) (1.00) (1.00) (1.00) (105.2) * (54.8)* (23.6)* B-C 0.83 0.60 0.91 0.64 205.3 * 289.2* 27.6* (1.00) (0.67) (1.00) (0.68) (171.2) * (273.6)* (16.6)* (TABLE 3 continued on next page) 37 TABLE 3 (continued) Raw univariate statistics: Means (medians) by origin, sample period: 1984-2001a Panel B: Civil Law Origin – French, German, and Scandinavian French vs. German French German Scand. t- stat. Variablesb Originf Origing Originh (Z- stat.)e HORIZ 132.7 139.7 127.4 -10.8 * (111.0) (118.0) (99.0) (-12.1) * CHANGE 0.20 0.22 0.21 -9.50 * (0.00) (0.00) (0.00) (-9.50) * EXP 0.59 0.60 0.54 -3.64 * (0.69) (0.69) (0.69) (-1.71) COMP 27.7 27.6 19.3 0.87 (14.0) (15.0) (10.0) -(5.43) * SPEC 0.47 0.56 0.52 -42.4 * (0.40) (0.57) (0.50) (-41.9) * FREQ 3.04 2.94 3.07 4.79 * (2.00) (2.00) (2.00) (16.6) * B-SIZE 0.84 0.86 0.84 -15.6 * (0.89) (0.90) (0.92) (-3.38) * B-IND 0.10 0.11 0.17 -3.41 * (0.08) (0.08) (0.11) (-0.98) PIN 0.39 0.33 0.38 43.1 * (0.34) (0.27) (0.35) (44.9) * POUT 0.28 0.28 0.27 0.07 (0.23) (0.22) (0.25) (4.71) * C-EXP 0.29 0.36 0.25 -25.7 * (0.00) (0.00) (0.00) (-25.6) * C-SPEC 0.77 0.82 0.66 -23.2 * (1.00) (1.00) (0.86) (-29.4) * B-C 0.59 0.69 0.42 -40.8 * (0.59) (0.94) (0.29) (-33.2) * a French vs. Scand. t- stat. (Z- stat.)e 5.65* (5.85)* -3.25* (-3.30)* 9.90* (9.29)* 28.2* (37.1)* -16.2* (-18.8)* -1.33 (-10.0)* -0.67 (-2.64)* -49.6* (-38.0)* 2.45** (0.53) 14.9* (-4.11)* 10.1* (10.2)* 10.4* (37.3)* 53.7* (45.6)* German vs. Scand. t- stat. (Z- stat.)e 12.9 * (13.7) * 2.79 * (2.76) * 12.1 * (9.84) * 26.8 * (40.0) * 10.3 * (13.0) * -5.09 * (-20.9) * -10.2 * (-0.14) -63.1 * (-36.4) * -27.0 * (31.7) * 6.61 * (-8.41) * 27.0 * (25.4) * 47.3 * (57.3) * 81.4 * (74.3) * Unadjusted raw amounts for mean and median are reported since subtracting annual firm-year means for each variable produces means equal to zero. b Independent variables: HORIZ = The number of calendar days between the forecast issue date and the earnings announcement date. CHANGE = Dummy variable that takes a value 1 (0 otherwise) when there has been a change in the assignment of specific analyst k following company j for a particular brokerage in year t. EXP = The natural log of the number of years analyst k has issued forecasts for company j. COMP = The number of companies followed by analyst k in the calendar year in which the forecast was issued. SPEC = Percentage of companies followed by analyst k with the same I/B/E/S industry code as company j (1.00= 100%). FREQ = Number of forecasts issued by analyst k for company j in year t. 38 B-SIZE = B-IND = PIN = POUT = C-EXP = C-SPEC = B-C = Percentile ranking of the total number of analysts employed by the brokerage house to which analyst k belongs in the calendar year in which the forecast was issued, relative to other brokerage houses (1.00= 100%). Percentage of analyst k’s brokerage house analysts which follows company j’s industry in the calendar year in which the forecast was issued (1.00= 100%). Portion of new analysts that come from outside the brokerage house relative to the total number of analysts who worked for analysts k’s brokerage house during the calendar year in which the forecast was issued (1.00= 100%). Portion of analysts who left analyst k’s brokerage house relative to the total number of analysts who worked for analysts k’s brokerage house during the calendar year in which the forecast was issued (1.00= 100%). Dummy variable that takes a value of 1 (0 otherwise) when analyst k has issued forecasts for more than three years for any company in a country. Percentage of companies followed by analyst k in the same country where the analyst has issued forecasts for company j in year t (1.00= 100%). Percentage of analyst k’s brokerage house analysts which follow company j’s country in the calendar year in which the forecast was issued (1.00= 100%). c Countries in the common law origin are Australia, Canada, Hong Kong, India, Ireland, Malaysia, New Zealand, Singapore, South Africa, Thailand, United Kingdom, and the United States. d Countries in the civil law origin are Argentina, Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Indonesia, Italy, Japan, South Korea, Mexico, Netherlands, Norway, Philippines, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Taiwan, and Turkey. e Amounts shown represent tests of differences in means (medians) between the two groups. f Countries in the French origin are Argentina, Belgium, France, Indonesia, Italy, Mexico, Netherlands, Philippines, Portugal, Spain, and Turkey. g Countries in the German origin are Austria, Germany, Japan, South Korea, Switzerland, and Taiwan. h Countries in the Scandinavian origin are Denmark, Finland, Norway, and Sweden. *, ** Significant at p < 0.01, 0.05. 39 TABLE 4 Regression of analyst relative forecast accuracy on analyst- broker-specific characteristics, sample period: 1984-2001. U.S. vs Non-U.S. Non-U.S Common Non-U.S. Common vs Common Civil Common vs Civil Common Civil Predicted Law Law United Law t-stat.d t-stat.d t-stat.d Variablesa Sign Originb Originc States Origin H1: H2: H3: Intercept -0.0019 -0.0030 0.0001 -0.0056 0.30 1.30 -0.55 (-0.91) (-0.99) (0.04) (-0.87) HORIZ + CHANGE -/? EXP - COMP + SPEC -/? FREQ - B-SIZE - B-IND - PIN + POUT + C-EXP - C-SPEC - B-C - Chow-F e R2 Obs. 0.0037 0.0023 (170.2)* (78.4)* -0.0132 0.0018 (-4.17)* (0.31) -0.0037 0.0038 (-1.39) (0.73) 0.0002 -0.0001 (2.88)* (-1.13) -0.0551 0.0076 (-7.86)* (0.72) -0.0397 -0.0156 (-51.3)* (-13.5)* -0.220 -0.040 (-18.6)* (-1.87) -0.0318 0.1760 (-2.16)** (4.60)* 0.0420 0.0367 (4.88)* (3.17)* 0.1385 0.0888 (15.7)* (7.42)* 0.0082 0.0086 (2.92)* (1.55) -0.0418 -0.0239 (-3.72)* (-2.58)** -0.0734 -0.0784 (-11.3)* (-8.63)* 0.0038 0.0031 (149.3)* (82.0)* -0.0227 0.0119 (-6.23)* (1.86) 0.0011 0.0047 (0.35) (0.79) 0.0007 -0.0004 (6.18)* (-2.95)* -0.0620 -0.0260 (-7.39)* (-1.96)** -0.0535 -0.0356 (-54.5)* (-33.2)* -0.230 -0.080 (-17.8)* (-2.99)* -0.0250 -0.0218 (-1.60) (-0.44) 0.0296 0.0512 (2.76)* (3.50)* 0.1632 0.0920 (14.7)* (6.48)* 0.0076 0.0077 (2.27)** (1.39) -0.0636 -0.0402 (-2.63)* (-2.98)* -0.0908 -0.0351 (-10.0)* (-3.44)* 0.1419 0.0811 535,462 138,355 0.1494 390,121 a 36.3* 14.2* 16.2* -2.29** -4.70* 1.18 -1.28 -0.54 0.10 2.77* 6.32* -4.97* -2.28** -1.99** -16.9* -12.3* -12.4* -6.89* -4.70* -1.17 -5.07* -0.06 -3.16* 0.37 -1.19 0.78 50.4* 3.95* -1.70 0.18 -0.07 -0.02 -0.11 -1.23 -0.48 -1.00 0.46 -4.09* 8.31* 237.6 * 75.5* 76.0* 0.1271 145,341 Independent variables are defined in Table 3 and country classifications are defined in Table 1. White adjusted tstatistics are reported in parentheses. b Common law countries are Australia, Canada, Hong Kong, India, Ireland, Malaysia, New Zealand, Singapore, South Africa, Thailand, United Kingdom, and the United States. c Civil law countries are Argentina, Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Indonesia, Italy, Japan, South Korea, Mexico, Netherlands, Norway, Philippines, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Taiwan, and Turkey. d Amounts shown represent tests of differences in coefficient betweens the two groups. e The Chow statistics test that the vectors of estimated coefficients are the same for the two groups. *, ** Significant at p < 0.01, 0.05. 40 TABLE 5 Regression of analyst relative forecast accuracy on analyst- broker-specific characteristics in the Civil law countries, sample period: 1984-2001. Variablesa Intercept Pred. Sign HORIZ + CHANGE -/? EXP - COMP + SPEC -/? FREQ - B-SIZE - B-IND - PIN + POUT + C-EXP - C-SPEC - B-C - Chow-F f R2 Obs French Originb -0.0025 (-0.60) 0.0025 (60.9)* 0.0011 (0.13) -0.0142 (-1.84) -0.0004 (-3.31)* 0.0138 (1.01) -0.0070 (-5.00)* -0.0011 (-3.40)* 0.1856 (3.19)* 0.0106 (0.73) 0.0877 (4.91)* 0.0078 (0.96) -0.0319 (-2.69)* -0.0613 (-4.99)* German Originc -0.0028 (-0.52) 0.0020 (41.6)* -0.0030 (-0.34) 0.0276 (3.45)* 0.0001 (0.97) 0.0208 (1.05) -0.0259 (-11.7)* 0.070 (1.74) 0.2544 (3.60)* 0.0955 (4.42)* 0.0811 (4.73)* 0.0097 (1.16) -0.0011 (-0.06) -0.1084 (-7.25)* Scand. Origind -0.0085 (-1.02) 0.0025 (24.8)* 0.0304 (1.71) -0.0026 (-0.16) 0.0007 (1.90) -0.0679 (-2.42)* -0.0179 (-4.83)* -0.020 (0.32) 0.1253 (1.70) -0.0376 (-1.01) 0.1454 (3.10)* 0.0089 (0.51) -0.0176 (-0.70) -0.1100 (-3.10)* 0.0881 70,011 0.0711 52,951 0.0980 15,393 a French vs German t-stat.e 0.05 8.29* French vs Scand. t-stat.e 0.65 German vs Scand. t-stat.e 0.58 0.90 -4.28* -0.33 -1.49 -1.68 -3.76* -0.63 1.63 -2.61* -2.77* -1.40 -0.29 2.62* 7.23* 2.76* 2.59* -1.85 -3.55* -1.16 1.10 -0.75 0.64 1.27 3.26* 1.20 3.09* 0.27 -1.15 -1.29 -0.16 -0.02 0.01 -1.40 -0.51 0.53 2.44** 1.30 0.04 76.6* 49.8* 60.8* Independent variables are defined in Table 3. White adjusted t-statistics are reported in parentheses. Countries in the French origin are Argentina, Belgium, France, Indonesia, Italy, Mexico, Netherlands, Philippines, Portugal, Spain, and Turkey. c Countries in the German origin are Austria, Germany, Japan, South Korea, Switzerland, and Taiwan. d Countries in the Scandinavian origin are Denmark, Finland, Norway, and Sweden. e Amounts shown represent tests of differences in coefficients between the two groups. f The Chow statistics test that the vectors of estimated coefficients are the same for the two groups. *, ** Significant at p < 0.01, <0.05. b 41