LAW AND ECONOMICS:

advertisement

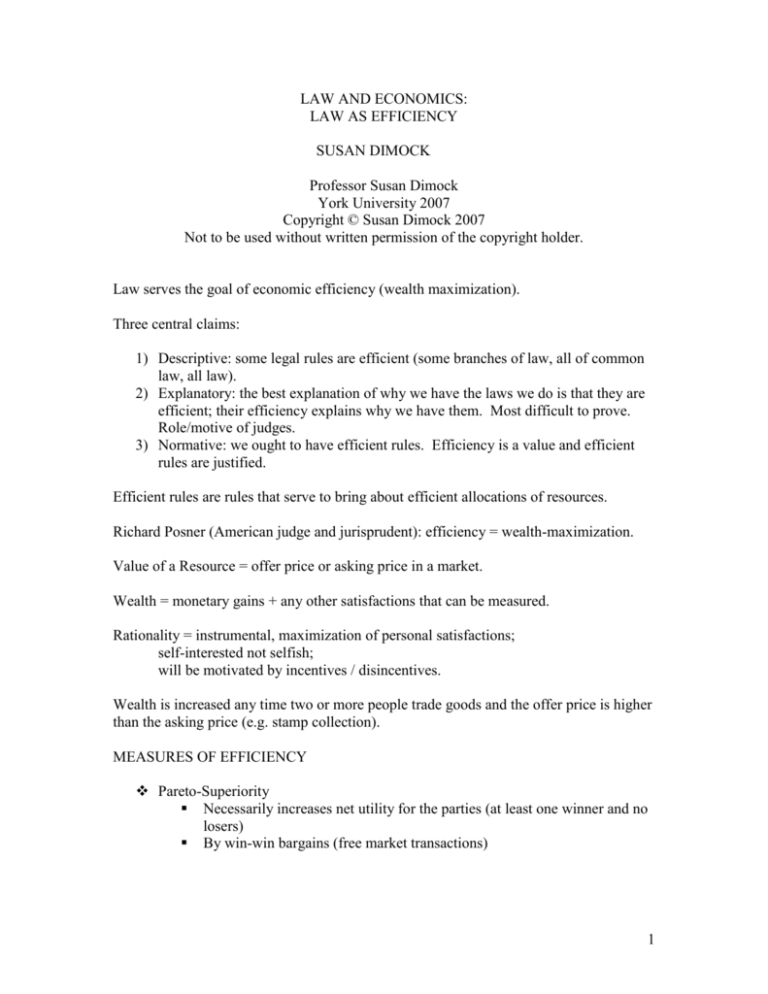

LAW AND ECONOMICS: LAW AS EFFICIENCY SUSAN DIMOCK Professor Susan Dimock York University 2007 Copyright © Susan Dimock 2007 Not to be used without written permission of the copyright holder. Law serves the goal of economic efficiency (wealth maximization). Three central claims: 1) Descriptive: some legal rules are efficient (some branches of law, all of common law, all law). 2) Explanatory: the best explanation of why we have the laws we do is that they are efficient; their efficiency explains why we have them. Most difficult to prove. Role/motive of judges. 3) Normative: we ought to have efficient rules. Efficiency is a value and efficient rules are justified. Efficient rules are rules that serve to bring about efficient allocations of resources. Richard Posner (American judge and jurisprudent): efficiency = wealth-maximization. Value of a Resource = offer price or asking price in a market. Wealth = monetary gains + any other satisfactions that can be measured. Rationality = instrumental, maximization of personal satisfactions; self-interested not selfish; will be motivated by incentives / disincentives. Wealth is increased any time two or more people trade goods and the offer price is higher than the asking price (e.g. stamp collection). MEASURES OF EFFICIENCY Pareto-Superiority Necessarily increases net utility for the parties (at least one winner and no losers) By win-win bargains (free market transactions) 1 By win-lose transactions with full compensation, so long as gains to winner are large enough to leave him/her better off even after compensation has been paid to the loser(s) – e.g., pollution Efficient because wealth-maximizing. Pareto-Optimality No further transactions can be made that will make one party better off without making at least one other worse off. Only good if achieved through Pareto-superior moves. PROBLEM: there are almost no Pareto-superior choices available in law or politics; there are almost always winners and losers. Kaldor-Hicks Allows transactions that make at least one person worse off (the loser) provided the gains to the winner are large enough that full compensation could be paid to the loser and still realize a net benefit to the winner. Wealth-maximizing. But compensation not actually paid; if actually paid, it would be Paretosuperior. PRINCIPLES OF EFFICIENCY MAKE SENSE OF: Place of free voluntary market transaction in law and economics: law protects and facilitates free market transactions. Market failures: third party effects, externalities; use Kaldor-Hicks to determine if permissible; use law to enforce actual compensation when efficient to do so, thereby achieving results that mimic the market. Transaction costs. LEGISLATORS AND JUDGES Legislators Cannot and generally do not pursue efficiency. Primarily redistributive: if goal is to correct market failures or support markets, may be efficient; otherwise not. Judges Cannot generally engage in large-scale redistribution, but can achieve efficiency. Deal with market failures: torts, contracts, property, nuisance, crimes, safety. Provide dispute mechanisms that are as efficient as possible. TORT LAW Plaintiffs v. Defendants; compensation for damages. 2 Not all loses are actionable; whether a loss is actionable is itself decided by efficiency considerations, e.g., losses through market competition. Actions that are actionable, e.g. accidents. Efficient number / kind of accidents. How to reduce future accidents and their costs to optimal levels by altering the price of certain behaviours. Affected by regulations, licensing, etc. Based on risks vs. benefits. How to provide incentives for accident prevention and harm reduction. Accidents: who should bear the costs? 1) Socialized insurance: everyone pays through social insurance scheme; generally inefficient because does not provide incentives for accident avoidance and harm reduction 2) Negligence: the injurer pays the cost of the accident if he/she was negligent (did not take reasonable care). If the injurer not negligent, the victim bears the cost. 3) Absolute victim liability: the costs of accidents lie where they fall; victims bear their own costs, whether or not the person causing the accident was negligent. 4) Absolute injurer liability: the injurer bears the cot of the accident, whether or not the injurer was careless or otherwise at fault. Different rules provide different levels of incentive for accident reduction and place the cost of reducing accidents on different parties. Negligence defined by Efficiency: Learned Hand’s Cost-Justified Precautions Principle Only cost-justified precautions against accidents are reasonable, and so, if avoiding an accident is not cost-justified, the person was not negligent for failing to avoid it. The expected loss from an accident (its costs) is a function of the probability of that type of accident occurring (P) multiplied by the magnitude of the loss should the accident occur (L). The cost of taking care (the burdens of precaution) is B. Negligence is the failure to take care when the cost of B is less than the expected cost of the accident (PL): when B < PL. Many exceptions: ultra-hazardous activities in which PL is so high that no effective burden of precaution B could be borne by potential victims(B always greater than PL) 3 Efficiency empirical and contingent on actual costs, probabilities and possible preventions. Sometimes a negligence standard, sometimes an absolute liability rule will be best. Alternative Proposal: Tort law is designed to achieve compensatory justice rather than efficiency. Compensation is due: when A causes harm to B by violating B’s property rights; A imposes non-reciprocal risks on B that harm B; A acquires a wrongful gain by imposing a loss on B; A wrongly harms B; etc. Efficiency can be seen to do justice too. It is wrong for one person to fail to take precautions against harming others when those precautions cost less than the harm risked by failing to take them. If the harm actually comes about, then it must be rectified. And it is the injurer who must pay, because otherwise the injurer would not bear the full cost of his/her negligent behaviour. Justice and Efficiency require the same thing. CONTRACT LAW Specified which agreements are legally binding and which are not. Specifies the rights and duties created by enforceable but unclear or incomplete agreements. Specifies the consequences of an unexcused breach. Serves efficiency by: Maintaining incentives to efficient exchange; Reducing transactions costs; Requiring “consideration” for enforceable contracts or promises; Requiring that some details be made explicit (e.g., price); Rendering unenforceable certain contracts: mistake, ignorance, duress or coercion, lack of capacity to understand the undertaking because of youth, mental disorder or intoxication. Breaches: Contract law does not eliminate breaches, but works to ensure that only efficient breaches occur. Three types of damages: Expectation measure of damages (Pareto-superior) Reliance measure of damages Restitution (unjust enrichment) PROPERTYLAW 4 Rules for protecting property rights. Exclusive rights to things that are valued and scarce. Personal and real property, our bodies, labour and ideas. Rights should be vested in whoever values them most. Usually natural owners. Property law protects entitlements and their productive use and transfer. Property Rules: entitlements only extinguishable by ex ante agreement. Liability Rules: allow non-voluntary transfers of entitlements provided compensation is paid ex post. Inalienability Rules: prohibit some transfers of rights; protect rights that no rational person would willingly alienate, or those that can only be enjoyed collectively. Criticisms: Value depends on willingness to pay, which depends on ability to pay. Ability to pay will depend upon on initial distribution of property rights. Does not support equal distribution of property rights, even from an equal initial distribution. Market transactions disrupt equality. CRIMINAL LAW Rules protecting property (against theft, robbery, vandalism) provide holders of goods assurances of their future enjoyments of their entitlements. Promotes market transactions by fixing the resources with which people can enter into agreements with others. Prevent non-wealth-maximizing transfers. Rules against force and coercion also prevent non-wealth-maximizing transfers. Rules against personal violence protect productive labour. Protects interests that are vitally important and best protected collectively. When is it efficient to use criminal law rather than some other method of behaviour control? Probability X loss suffered by victim of crime (PL) Cost of preventing crime (C) Only if PL > C should we use criminal law. What overall expenditure and distribution of funds should we spend on crime control? 5 What level of enforcement and scheme of penalties will induce compliance with the law? What is an efficient rate of penalties? Deterrence: severity of penalty + likelihood it will be imposed. Optimal price of care theft = price of crime to others (say $4000) ÷ perfect enforcement (1.0) = $4000. The price at which crime will not pay, the price at which a rational criminal will be deterred. But when enforcement is not perfect, the efficient penalty will be a function of the optimal penalty and the probability of the penalty being imposed. Efficient penalty for car theft = price of crime to others (optimal penalty) $4000 ÷actual enforcement (0.5) = $8000. THE NORMATIVITY OF WEALTH MAXIMIZATION Can ground central legal rights (life, liberty and labour). Supports economic liberty. Can explain the importance of rules requiring promise keeping and truth telling. Can explain virtues such as industriousness, intelligence, etc. Can explain the importance of altruism and charity, private and public. 6