Mr Hooke - the hidden face of genius

advertisement

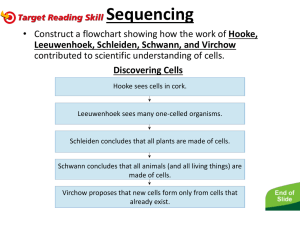

Mr Hooke - the hidden face of genius The Royal Society, Library and Information Services. Robert Hooke (1635-1703) has been described as the British Leonardo and the world's first professional scientist. His name is linked to a range of disciplines that today would be represented by an entire university science faculty. It is hard to look around a room or travel down a London street without seeing or using something whose design owes much to his research. Bed springs, the universal joint (used in cars), sash windows, cameras, watches, and even the street layout of London all bear the mark of his genius. Hooke's ability to apply his enquiring mind to such a diverse range of disciplines and problems is today seen as an achievement. But when he was alive, his tendency to explore a bit of everything (and, some would say, complete very little) irritated many of his more specialised contemporaries, even though they were often to benefit from his work. The hostility between Hooke and Isaac Newton is legendary, and may well have contributed to the subsequent lack of recognition for his work. Hooke drew this ant under the microscope Hooke's Law illustrated Hooke's achievements can be appreciated by following his involvement with the Royal Society, where he served as Original Fellow (elected in 1663), first Curator of Experiments (1662-1688), Secretary (1677-1682) and Council member (five separate spells). This association means the Society's archives are rich in Hooke's material, and this exhibition marks the tercentenary of his death with a display of his publications, original manuscripts showing his scientific discoveries, and one of his many "to do" lists. The post of Curator of Experiments represented the first professional job for a scientist, and it was here that Hooke really made his mark. Working at a time when science was moving from "a work of the brain and fancy" to the investigation of material things, he was expected to devise and perform his own experiments to Fellows, as well as to design equipment and tests for ideas recommended by the Society. Hooke published a number of papers and documents detailing the investigations he undertook for the Society. His masterpiece, the first scientific discourse on microscopy, Micrographia, came out in 1665, and is on display in the exhibition. Samuel Pepys records in his diary: Before I went to bed, I sat up till 2 a-clock in my chamber, reading of Mr. Hooke’s Microscopicall Observacions, the most ingenious book that ever I read in my life. (21 January 1665). Micrographia was remarkable in many ways. It covered 60 topics including plants, animals and insects, silk and flax, hair, feathers and scales. Intricate diagrams and exquisite drawings were accompanied by a lively commentary. The text was in English rather than Latin, which made it accessible to many more people. Furthermore the page on the structure of cork includes Hooke's realisation that products found in nature are made up of small units, which he describes as cells - the first use of the word in this context. It is ironic that no portrait of Hooke survives, given the prominent role he played in the founding of British science, and the number of paintings that we have of many of his contemporaries. We know that there was a portrait, but it mysteriously disappeared along with many of Hooke's papers and instruments at around the time the Society moved from its first home at Gresham College in 1710. It is perhaps no coincidence that Newton was President at the time! Detailed written descriptions of Hooke, however, have survived, and these give us a good idea of what he looked like, including his 'head of haire' being 'of an excellent moist curle'. Portraits developed from these descriptions by artists from the Royal College of Art and the London College of Printing are on display in the Exhibition.