Creating a Dune - College of Charleston

advertisement

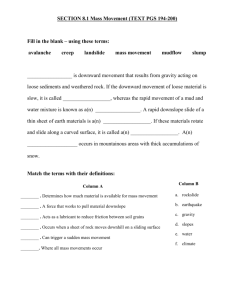

Build Me Up Based on an activity by Barb Hawkins, http://www.askeric.org Focus Question How does Spartina help to create sand dunes? Activity Synopsis Students observe the effects of wind on two pans of sand. One pan contains sand only. The second pan contains sand and plant material representing the wrack line. Time Frame 30-45 minutes Student Key Terms Spartina salt marsh tides wrack line dune primary dune secondary dune wrack line desiccating substrate succulent Objectives The learner will be able to: Observe how sand dunes are formed. Explain the importance of the wrack line in dune formation. First Grade Standards Addressed Science Standards IA1a, IA4a, IB1a, IIC2a, IVB1a Background Relevant pages in: Keener-Chavis, Paula and Leslie R. Sautter. 2002. Of Sand and Sea: Teachings from the Southeastern Shoreline. S.C. Sea Grant Consortium, Charleston, SC, pp. 61-62. From COASTeam Aquatic Workshops: The Coast (grade 1); a joint effort between the COASTeam Program at the College of Charleston and the South Carolina Aquarium – funded by the SC Sea Grant Consortium 1 Key Points Key Points will give you the main information you should know to teach the activity. The most common plant in southeastern salt marshes is Spartina alterniflora, or smooth cordgrass. Spartina leaves die each autumn and some are washed out to sea with the tides. Waves then wash the decaying Spartina leaves back onto the shore, where they form the wrack line. The wrack line indicates the high tide mark. Wind-blown sand hits the wrack line and falls from the air. Sand then begins to accumulate around the wrack line and the formation of a primary dune has begun. Detailed Information Detailed Information gives more in-depth background to increase your own knowledge, in case you want to expand upon the activity or you are asked detailed questions by students. In the autumn months, the leaves of Spartina die and begin to decay. Most of the decaying plant material remains in the marsh, forming the base of the marsh food web. Some of the material, however, is swept into the inlets with the rising and falling tides and is washed out to sea. From there, wave action pushes the plant material back onto the beaches forming the easily recognizable wrack line. The wrack line runs the length of the beach and marks the place where the tide reaches its highest point. When sand is blown over the wrack line by the wind, it falls out of the air and begins to accumulate around the wrack line. Sand continues to accumulate and a dune has begun to form! Seeds entrapped in the wrack have the perfect place to germinate – moist with a lot of nutrients. As the plants grow, their roots keep them stabilized in the shifting sands. The continued accumulation of sand provides a more stable zone for growth. The wrack line is on its way to becoming a primary dune. Primary dunes are often called the deserts of the beach. Inhabitants must have adaptations to deal with harsh conditions including desiccating (drying) winds, salt spray, rapid water drainage, shifting substrate and high solar radiation. Some of these adaptations include thick, succulent leaves, deep taproots to penetrate to the ground water, and extensive fibrous root systems that spread through the sand catching water as it drains through the sand. Sea oats have long curly leaves and tall oat heads that serve to trap wind-blown sand as it travels down the beach. The trapped sand begins burying the sea oats and all neighboring plants. Sea oats have adapted to grow vertical runners that produce new plants on the surface of the dune, thereby staying ahead of the accumulating sand. The neighboring plants are buried, die, and the decaying matter provides nutrients for the sea oats. For this reason, it is typical to see a dune covered only by sea oats. Since sea oats play such a From COASTeam Aquatic Workshops: The Coast (grade 1); a joint effort between the COASTeam Program at the College of Charleston and the South Carolina Aquarium – funded by the SC Sea Grant Consortium 2 vital role in dune formation, they are protected by law. Fines for destroying sea oats can reach as high as $200 per plant! Secondary dunes are located behind the primary dunes. Since the primary dunes are blocking most of the desiccating winds and salt spray, secondary dunes are more stable. This added stability allows for greater plant diversity. Many shorebirds nest in dunes. Raccoons, mice, rats, opossums, rabbits, snakes, lizards and foxes forage in the primary and secondary dunes (Keener-Chavis, p.63). The Loggerhead sea turtle uses the dunes as a nesting area. In addition to being important wildlife habitat, sand dunes serve as the first line of defense for the mainland. Dunes help to absorb the impact of unusually high tides, nor’easters, and storm surges. Sand dunes may be thought of as reservoirs of sand. They, too, suffer erosion during a storm surge; however, the sand is washed offshore and is then available for re-deposit on the beach! There are various methods of creating or repairing sand dunes. In an attempt to speed up the formation of sand dunes, some areas have chosen to build sand fences. Sand fences act in much the same way as the wrack line or the tall sea oat blades – they slow wind velocity and cause sand to be deposited. Sand fences should be built above the reach of storm waves and near the natural line of dunes and vegetation. Once the dunes begin to accrete, they should be vegetated with native plants to help hold the newly formed dune in place. In some areas, large amounts of native vegetation are planted with the hopes of creating a dune line. And, finally, one of the more unique ideas: using recycled Christmas trees beachfront to trap sand and begin dune formation! Procedures Materials Two large pans Sand (enough to nearly fill both pans) Hair dryer (if you split the students into groups, each group will need a hair dryer) Small sticks Procedure 1. Do this activity on a smooth surface. The sand does not stay in the pan! Also make sure that no one is standing eye-level with the pan of sand. 2. Begin by asking the students to describe a day at the beach. What do they see? What do they do? Where do they put their chairs and beach towels? When they walk from their car to the beach, do they have to walk over anything? Can they see the ocean from their car? (The answers to the last two questions may vary depending on what beach the student visits! From COASTeam Aquatic Workshops: The Coast (grade 1); a joint effort between the COASTeam Program at the College of Charleston and the South Carolina Aquarium – funded by the SC Sea Grant Consortium 3 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. Hopefully they are visiting a beach with sand dunes and will remember that they must use a walkover to get over the dunes. If, however, the students frequent Folly Beach, for example, you may need to prompt them with pictures.) Explain that the “things” that block their view of the ocean and the “things” that they must walk over (either over a boardwalk OR by a walkthrough) are called sand dunes. How do you think sand dunes get there? Why does the sand pile up in that place? Ask the students if they remember that in the life cycle of Spartina, the dead leaves were washed up on shore. The dead leaves form the wrack line. Has anyone seen the pile of brown stuff near the top of the beach? Has anyone played in that? Has anyone looked for shells or other sea critters in the wrack line? Explain to the students that we will see how the wrack line begins the formation of sand dunes. Show the students the two pans. Label the pans A and B. Fill both pans with sand, leaving about an inch of the pan empty. Tell the students the two pans represent two beaches. One of our beaches has a wrack line and one does not. Have a couple of students help you create a wrack line with the small sticks. The sticks must be heavy enough to NOT be blown away with the hair dryer! You may wish to also put in seashells, since some students may have made this observation from their personal experiences. Flat blocks are another option. Ask the students how the beach feels. What do they notice while they’re at the beach? Do they feel wet? Does the wind blow? Does sand blow in their eyes? Tell the students that you will use a hair dryer to represent the wind blowing at the beach. Using the low setting, hold the hair dryer at a 45-degree angle approximately 10-12 inches from one end of the sand only pan for one minute. What is the wind doing to the sand – is it pushing or pulling the sand? How is the sand moving in relation to the wind (does the wind push the sand away or pull the sand toward it)? What do the students observe? What happened to the sand? If the students observe that the sand is piling up at the end of the pan, have them imagine the end of the pan isn’t there. What would happen if the sand was blowing down the beach and the end of the pan wasn’t there to stop the movement? Have each student draw a picture of what the sand looks like in the pan. Now repeat #7 with the wrack line pan. Explain that the sticks represent the wrack line on the beach. What do the students notice? Is the sand building up around the sticks? Have each student draw a picture of the sand in the pan. . Assessment Using his/her pictures of the two pans, have each student explain how the wrack line affects dune formation. From COASTeam Aquatic Workshops: The Coast (grade 1); a joint effort between the COASTeam Program at the College of Charleston and the South Carolina Aquarium – funded by the SC Sea Grant Consortium 4 Mastery/Nonmastery: The student correctly explains that (1) the wind pushes the sand down the beach, (2) the wrack line slows down the sand, and (3) the sand begins to build up around the wrack line. Members of the COASTeam Aquatic Workshops development team include: Katrina Bryan, Jennifer Jolly Clair, Stacia Fletcher, Kevin Kurtz, Carmelina Livingston, and Stephen Schabel. From COASTeam Aquatic Workshops: The Coast (grade 1); a joint effort between the COASTeam Program at the College of Charleston and the South Carolina Aquarium – funded by the SC Sea Grant Consortium 5