Teaching Syllabus - Albert Einstein College of Medicine

advertisement

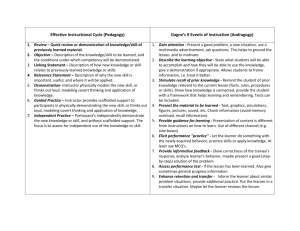

TEACHING TEACHERS TO TEACH Hanah Polotsky, M.D. & Eva Metalios, MD Montefiore Medical Center Albert Einstein College of Medicine Cow philosophy Who was your finest teacher? What were the characteristics that made this teacher excellent? ANALYSIS OF TEACHING A – Excellent B – Good C – Fair D – Poor Characteristics Tape # 1 Tape # 2 Tape # 3 _____________ ___ ___ ___ _____________ ___ ___ ___ _____________ ___ ___ ___ _____________ ___ ___ ___ _____________ ___ ___ ___ _____________ ___ ___ ___ TEN TIPS TO BECOMING A BETTER TEACHER 1. Consider your goals and objectives and communicate them to your learner. 2. Discover enthusiasm for your subject and your learners. 3. Take your teaching and their learning seriously - plan, teach, reflect. 4. Rediscover your sense of humor. 5. Make your learner as active as possible. 6. Be respectful of your learners. 7. Promote self-directed learning. 8. Provide frequent, timely, constructive feedback. 9. Admit your limitations - relearn to say, "I don't know". 10. Make your teaching and their learning fun. THE CASE OF THE PAINFUL EAR CONTEXT: A resident in clinic comes to you while you are precepting. The resident appears bright and eager to learn. RESIDENT:" Ms. R is a 52-year-old woman with hypertension, CHF, obesity, and high cholesterol who comes to clinic for a routine visit. She says she is feeling "OK"—no chest pain, PND, orthopnea, dyspnea on exertion. She is not having any problems with her medication, and tells me she is taking them as directed. She does tell me, though, that she has been having a pain in her right ear since Monday. She has this full feeling, some itchiness, and some clear discharge. She mentioned she is having some problems hearing on that side, too. She denies Q-tip use, a sore throat, sick contacts, or a cough—but she was at her local pool over the weekend. She has no allergies to medications. She took some Tylenol last night and again this morning and that did not really help, the pain is getting worse. On exam her vitals are stable; BP is 130/82, HR 86, RESP 12, and she is afebrile. On the HEENT her nose is a little congested with clear discharge, but there is no sinus tenderness. I think the right tympanic membrane is clear, but the canal is red and there is some stuff in there. But I am not sure, though; I haven't seen many infected ears. It did look different from the left one. There was no adenopathy on the neck. Her throat and lungs were clear. That is it really..." ATTENDING: “This is an obvious case of otitis externa. Prescribe cortisporin otic solution, renew her medications, and have her come back to the clinic in three months." ALTERNATIVE STRATEGY: The same case was presented on rounds: ATTENDING: "What do you think is going on?" RESIDENT: "I think that ear is infected, maybe an otitis externa." ATTENDING: "OK, what led you to that conclusion?" RESIDENT: "She had a full feeling in the ear, denied fever, there was some discharge, and her canal was red." ATTENDING: "What would you like to do?" RESIDENT: "Well first I would like you to look at that ear with me. If you think it is infected, then we should give her some antibiotics. With no allergies to medicine I would use cortisporin otic solution." ATTENDING: "You did a great job of putting her history and physical exam together into a coherent whole. It does sound like an otitis externa, several days of itch, pain, discharge and diminished hearing in a patient who has recently been swimming. In her case the hearing problem she noted is likely a conductive hearing loss and secondary to the otitis, but we should not assume this. I did not hear you report that you checked her hearing when you examined her, though you mentioned she complained of hearing problems. It is important to do a Rhine and Weber test on patients with hearing loss. With an otitis externa, cortisporin drops are a good choice. Let’s go look at that ear together, then go from there.” FIVE MICROSKILLS FOR CLINICAL TEACHING Clinical teaching frequently occurs in a setting where time is at a premium. In order to be an effective teacher, we find ourselves balancing three distinct tasks. First you diagnose the patient; what is his/her medical issue, how can it be managed. Second, you diagnose the learner; what does he or she understand about the case and why. Third, you teach around the case. This can be a lot to accomplish given the time constraints of medical teaching. David Irby has developed the "Five Microskills of Clinical Teaching". This teaching concept was designed for medical teaching in ambulatory settings, and proves a framework for quick and effective teaching. 1. GET A COMMITMENT "What do you think is going on?" 2. PROBE FOR SUPPORTING EVIDENCE "Why do think this is the case?' 3. REINFORCE WHAT WAS RIGHT "You did a good job with..." 4. CORRECT MISTAKES "Next time try..." 5. TEACH GENERAL RULES "The take home points are..." DIAGNOSE PATIENT DIAGNOSE LEARNER 1. GET COMMITMENT 2. PROBE FOR EVIDENCE TEACH 3. PROVIDE POSITIVE FEEDBACK 4. TEACH GENERAL RULES 5. CORRECT ERRORS Microskill 1: Get a Commitment Cue: After presenting the facts of a case to you, the learner either stops to wait for your response or asks your guidance on how to proceed. Preceptor: Instead, you ask the learner to state what s/he thinks about the issue presented by the data. Rationale: Asking learners how they interpret the data is the first step in diagnosing their learning needs. Without adequate information on the learner's knowledge, teaching might be misdirected and unhelpful. Examples "What do you think is going on with this patient?" "What would you like to accomplish in this visit?" "Why do you think the patient has been non-compliant?" Microskill 2: Probe For Supporting Evidence Cue: When discussing a case, the learner has committed him/herself on the problem presented and looks to you to either confirm the opinion or suggest an alternative. Preceptor: Before offering your opinion, ask the learner for the evidence that s/he feels supports her/his opinion. A corollary approach is to ask what other choices were considered and what evidence supported or refuted those alternatives. Rationale: Asking them to reveal their thought processes allows you both to find out what they know and to identify where there are gaps. Examples "What were the major findings that led to your conclusion?" "What else did you consider? What kept you from that choice?" Microskill 3: Tell Them What They Did Right Cue: The learner has handled a situation in a very effective manner. Preceptor: Take the first chance you find to comment on: 1) the specific good work and 2) the effect it had. Rationale: Skills in learners that are not well established need to be reinforced. Examples "You didn't jump into working up her complaint of abdominal pain, but kept it open until the patient revealed her real agenda. In the long run, you saved yourself and the patient a lot of time and unnecessary expense by getting to the heart of her concerns first." "Obviously you considered the patient's finances in your selection of a drug. Your sensitivity to this will certainly contribute to improving his compliance." Microskill 4: Teach General Rules Cue: You have ascertained that you know something about the case that the learner needs or wants to know. Preceptor: Provide general rules, concepts or considerations, and target them to the learner's level of understanding. A generalizable teaching point can be phrased as: "When this happens, do this..." Rationale: Instruction is both more memorable and more transferable if it is offered as a general rule, guiding principle or a metaphor. Examples "If the patient only has cellulitis, incision and drainage is not possible. You have to wait until the area becomes fluctuant to drain it." "Patients with UTI usually experience pain with urination, increased frequency and urgency, and they may have hemaiuria. The urinalysis should show bacteria and wbcs, and may also have some rbc's." Microskill 5: Correct Mistakes Cue: The learner's work has demonstrated mistakes (omissions, distortions, or misunderstandings). Preceptor: As soon after the mistake as possible, find an appropriate time and place to discuss what was wrong and how to avoid or correct the error m the future. Allow the learner a chance to critique his/her performance first. Rationale: Mistakes left unattended have a good chance of being repeated. Examples "You may be right that this child's symptoms are probably due to a viral upper respiratory infection. But you can't be sure it isn't otitis media unless you've examined the ears." "I agree that the patient is probably drug-seeking, but we still need to do a careful history and physical examination." “…also, while I’m here. I’ve got this pain in my back and a ringing in my ears. I’m telling you, sometimes I can’t hear myself think, which, I guess, is all right because I can’t remember a thing. Nothing I eat agrees with me, and I’m constipated. Now let me tell you about my knees…” In order for you to become a better teacher, you must first think of yourself as a teacher. As you work to improve your teaching skills, consider the following questions: 1. What makes a good teacher? What are the characteristics of the excellent teachers that I have encountered? What characteristics can I adapt as I work to make my teaching more effective? 2. What is my teaching style? What teaching methods and styles did I see demonstrated in the videotapes and role-plays? What teaching styles or methods can I use to make my teaching more effective? 3. How can / apply what has been discussed today to teaching in my own work setting? REFERENCES: Abrahamson S. Myths and Shibboleths in Medical Education. Teaching and Learning in Medicine. 1989; 1:4-9. Covey SR. The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People. Simon and Schuster, New York, 1990. Douglas KC, Hosokawa MC and Lawler FH. A Practical Guide to Clinical Teaching In Medicine. Springer Publishing, New York, 1988. Ende J. Feedback in Clinical Medicine. JAMA. 1983;250:777-81. Hekelman, FP, et al., Characteristics of Family Physicians' Clinical Teaching Behaviors in the Ambulatory Setting: A Descriptive Study. Teaching and Learning in Medicine, 1993. 5(1): P. 18-23 Hewson, M., Clinical Teaching in the Ambulatory Setting. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 1992.7:p.76-82. Hilliard RJ. The Good and Effective Teacher as Perceived by Pediatric Residents and by Faculty. AJDC. 1990;144:1106-1110. Irby, DM What Clinical Teachers in Medicine Need to Know. Academic Medicine, 1994,69(5):p.333-342. Irby,DM. Clinical Teacher Effectiveness in Medicine. J Med. Educ.1978,53:808-15. Irby, DM. Clinical Teaching and the Clinical Teacher. J Med. Educ. 1986;61 (9 Pt 2):35-45. Kroenke, K., Ambulatory Care: Practice Imperfect. American Journal of Medicine, 1986.80.-p. 339-342. Lesky, L.G. and S.C. Borkan, Strategies to Improve Teaching in the Ambulatory Medicine Setting. Archives of Internal Medicine, 1990.150: p. 2133-2137. Mattem, WD, D. Weinholtz, and C.P. Friedman, The Attending Physician as Teacher. New England Journal of Medicine, 1983.308: p. 1129-1132. Neher, JO.,Gordon, KC, Meyer, B., and Stevens, N. A Five-step "Microskills" Model of Clinical Teaching. Journal of the American Board of Family Practice. 5:419-424, 1992. Rubenstein W and Talbot Y. Medical Teaching in Ambulatory Care. Springer Publishing, New York. 1992. Schwenk TL and Whitman N. The Physician as Teacher, Williams and Wilkins, Baltimore, Maryland, 1987. Westberg, J., Jason, H. Collaborative Clinical Education: The Foundation ofEffecti\ Health Care. N.Y.: Springer Publishing Company, 1993. Whitman N. Creative Medical Teaching. University of Utah School of Medicine, Sail Lake City, Utah, 1990. Wilkerson, L., E. Armstrong, and L. Lesky, Faculty development for ambulatory reaching. Journal of' General Internal Medicine, 1990.5 (1 Suppl):p. s44-53. Woolliscroft, JO and Schwenk TL. Teaching and learning in the Ambulatory Setting. Academic Med. 1989;64:644-648