_The effects of exchange rate variations on firm prices in home and

advertisement

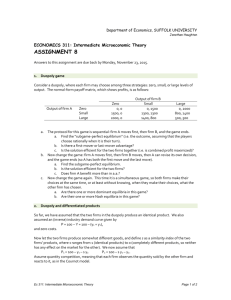

Pricing to Market at firm level Lourdes Moreno Martín Diego Rodríguez Rodríguez Universidad Complutense de Madrid and PIE-FEP Address: Fundación Empresa Pública Quintana 2, 3ª Planta 28008 Madrid Spain Phone: +34 91 5488357 Fax: +34 91 5488359 e-mail: drodri@funep.es 0 Resumen: Este trabajo analiza la influencia de las variaciones del tipo de cambio en los precios de los mercados domésticos y exteriores a partir de datos de empresas. El marco teórico está basado en la literatura de “Princing to market” pero es ampliado para considerar algunas hipótesis acerca de los efectos que las variaciones de la demanda y del poder de mercado tienen en el establecimiento de los precios por parte de las empresas. El análisis empírico se realiza para un panel incompleto de empresas manufactureras españolas en el período 1990-99. Se constata un efecto positivo de las devaluaciones de la peseta en este período en la evolución de los precios relativos (exportación/domésticos) pero, sin embargo, es cuantitativamente mucho menor que el obtenido en la abundante literatura empírica usando series temporales con datos industriales. Adicionalmente, los resultados sugieren el efecto positivo de las diferencias en el dinamismo de los mercados y cómo éste depende del grado de competencia de los mismos. Abstract: This paper studies the influence of exchange rate variations on prices in foreign and home markets. The theoretical benchmark, based on the literature of Pricing to Market strategies, is enlarged to take into account some hypothesis about the effects of demand variations and market power on prices. The empirical analysis for Spanish manufacturing firms (1990-1999) points out the positive impact of devaluations of the peseta in that period in the relative (export/domestic) evolution of prices, though the elasticity is smaller than using industry time series. Additionally, the results suggest the positive influence of the differences of market dynamism, but affected by the degree of competition. JEL Classification: F12, L60, L13 Key words: pricing to market, market dynamism, degree of competition 1 1. Introduction An extensive literature from the eighties has been devoted to analyze the effects of exchange rate variations on export (or import) prices. A general conclusion of those studies is the presence of an incomplete pass through from exchange rate to prices, probably related to country size, just as relevant industry differences1. An extension of this literature has focused in the differences of exchange rate pass through (EPT) to prices according to the destiny market. It probably implies a destination specific adjustment of markups and, thereby, some degree of price discrimination across markets. That circumstance is referred as Pricing to Market (PTM) strategy (Krugman, 1987). There are several perspectives in the studies of PTM strategies. One of them is represented by the fixed-effects model of Knetter (1989, 1993), that analyzes differences in price variations across export markets. The goal is to make conditional the observed variations in export prices to the common changes in costs and margins, both unobservable, which are approximated by a set of dummy variables: time effects and as in Knetter (1989), destination country effects. The relevant variations of prices are those based on markup variations specific by destiny markets. They are due to changes in the elasticity of demand perceived by firms, the exchange rate being the main explicative factor. The statistical contrast among several restrictions allows to determine what kind of effects (industrial, source country or destiny market) are the most relevant. An alternative approach is due to Marston (1990). This author identifies demand and cost conditions which generates different PTM elasticities, defined as changes in relative prices between foreign and home markets due to exchange rate variations. In this case the existence of PTM strategy is derived directly from regression and, therefore, it is not necessary to implement different restrictions on estimated parameters to test the existence of PTM strategies. In both cases the empirical approach is based on aggregate analysis. In that context, the main empirical problem is the difficulty to affirm the existence of price discrimination across 1 A survey of this literature can be seen in Menon (1995). 1 destiny markets, given those prices are probably referred to different products. It comes from the known problem about the accuracy of export prices, dues to they are approached by unit values in the majority of countries and, therefore, they have a composition-effect bias (Lipsey et al., 1991). Furthermore, the observed price differences across markets are probably also due to the distinct nature of firms. In that sense, Goldberg and Knetter (1997, p.1247) point out that “ideally, a test of Law of One Price would compose prices for two transactions in which the nationality of the buyers is the only difference in transaction characteristics. In practice, the identical goods assumption is almost surely violated to some degree in available data”. This paper address that criticism, extending the empirical approach of PTM literature, based on cross-industry analysis, to an empirical analysis based on firm data. Though the variable to explain is the same as Marston’s work (1990), the empirical approach adopted in this paper is nearer to Knetter’s model. That is because, as him, the objective is to isolate those price variations across markets that are only due to markup variations. Additionally, the theoretical benchmark is extended including some forecasts about price variations obtained in industrial organization literature. This is required because there are other arguments, different from exchange rate variations, which could contribute to explain the observed differences in price variations across markets. Particularly, the effects of demand variations and the degree of competition are included. The relevance about analyzing prices across markets at firm level has been considered by Aw et al. (2001). Using firm-level unit values, they obtain important price differences between foreign and home markets for Taiwanese firms. However, they do not relate such differentials with exchange rate or other explicative variables. Other recent studies, as Kadiyali (1997), analyze EPT at product level too. The explanatory benchmark is applied to analyze the differences in price variations among foreign and home markets for Spanish firms over the period 1990 to 1999. This period was especially relevant for the Spanish economy because of the changes experienced by the peseta in the context of the turbulence of the European Monetary System (EMS) in 1992-1993. Specifically, the peseta was devaluated in September and November 1992 (5% and 6%, respectively) and May 1993 (8%). Finally, the peseta suffered a final devaluation of 5% in May 2 1995. Furthermore, this period covers a complete cycle of the Spanish economy: the last years of the expansive period of the eighties, the fall in 1992-1993, and the recovery from 1994-1995. The main empirical result is the existence of PTM strategy for Spanish export firms. It implies that changes in national currency have been employed profitability by export firms, growing their relative (foreign/home) markups. Additionally, the differences in demand growth in both markets in this period have permitted them to rise their prices according to. We also find that the degree of competition in markets affect the degree of transmission from demand fluctuations to prices. However, we do not find this result for the exchange rate. The structure of the paper is as follows. Section 2 presents the theoretical benchmark to analyze the influence of exchange rate and other explicative variables in relative (foreign/home) prices. In Section 3 the empirical specification is proposed. The data, some descriptive indicators and the results of the econometric analysis are showed in Section 4. Finally, main conclusions are summarized in Section 5. 2. Theoretical benchmark We assume a monopolistic competition framework, where products are differentiated and each firm has some degree of market power. Each firm produces in home market and sells in two markets: one home (domestic) market in which sells to a price Pt, and one foreign (export) market selling to a price Qt in foreign currency. The firm faces home h(Pt) and foreign f(Qt) demands, having a joint cost function C [(h(Pt)+f(Qt)), zt] where zt is the input cost in the domestic market. Furthermore, we assume that gray markets do not run, and therefore that market segmentation is effective (households cannot arbitrage). The profit function of the firm can be written as follow2: t Pt h(Pt ) et Qt f (Qt ) Ct (h(Pt ) f (Qt )), z t where et is the exchange rate defined as home/foreign currency. Maximizing the profit objective function, assuming that both prices are the decision 2 We follow Marston (1990). 3 variables and that exchange rate is exogenous to the firm, we obtain the usual first order conditions: P t = C1 M( P t ) (1) e t Q t = C1 N(Q t ) (2) where C1 is the marginal cost and M and N are the markups of the domestic and foreign price (expressed in domestic currency) over marginal cost. Both of them can be expressed in terms of the demand price elasticities. Specifically, M(.) = /-1 and N(.)= /-1 where and are home and foreign demand elasticities. The effect of exchange rate variations on the foreign/home price ratio in domestic currency, defined as Xt=etQt/Pt , can be obtained differentiating the first order conditions and solving for domestic and foreign prices (P/e and Q/e). This effect is referred as Pricing to Market elasticity (1), and can be expressed by: 1 = X t et = 1 + 1 - 2 et x t where 1 (= e Q/ Q e) is the exchange rate pass through elasticity (EPT), which reflects the degree in which a variation of exchange rate is transmitted to export price in foreign currency Qt. The variation of export price in national currency is 1+1. Thus, export price in national currency is not affected by exchange rate change when there is a complete EPT (1=-1). The parameter 2 (=e P/ P e) gets the effect of exchange rate variation on home price P. As result, if 1 is not equal to zero then relative prices vary when the exchange rate does it too and, therefore, price discrimination between both markets would be observed. In a dynamic context with predetermined prices, a variation of relative prices Xt can also reflect a surprise effect due to non-anticipated variation of exchange rate. Giovannini (1988), Marston (1990) and Kasa (1992) face this problem in distinct ways, obtaining in all cases evidence in favor of discriminatory pricing beyond such surprise effect. In this paper, such effect is not considered because we assume that the temporal period of observations to be used in the empirical analysis (annual data) is sufficiently wide to allow firms to vary their prices, avoiding 4 the influence of delayed response3. The relative prices can also be expressed as a ratio of markups, assuming that the marginal costs are identical for both markets: Xt etQt N() Pt M() From this expression the PTM elasticity can be expressed as follow: X t et = 1 - 2 , 1 = et X t where and are the elasticities of markups (home and foreign, respectively) with respect to prices, both elasticities being expressed in terms of the elasticity of demand curve4. The PTM elasticity (1) will be zero if both markups are constant ( and = 0). A static comparative exercise allows us to analyze the effects of exchange rate variation on equilibrium price ratio. With constant marginal cost (C11=0) and constant foreign demand elasticity (q=0), 1=-1 indicating a complete EPT. In that case the foreign price in home currency would not change (which is logical given that C11 = N1 = 0). EPT will be incomplete (negative, but nearer to 0) when more concave is foreign demand schedule. If foreign demand was more convex that constant elasticity schedule, EPT would be smaller than –1. With increasing marginal costs (C11 > 0), a decrease in export price generates an increment in the demand, and therefore an increment in costs. In that case, export price in foreign currency will diminish in less proportion than exchange rate fluctuation. That incomplete exchange rate pass through (-1<1<0) implies an increase of export price in national currency (1+1 > 0). With respect to home price, if marginal costs are increasing (decreasing) home price will rise (fall), while constant marginal costs is a sufficient condition to let home price does not change. In the last case an apparently asymmetry is produced with respect to foreign price, in which constant marginal cost is not a sufficient condition. Nonetheless, in that case there is a 3 Additionally, when prices are predetermined the decision about the invoice currency for exports is a strategic variable for firms (see Giovannini, 1988). 5 direct effect of exchange rate variation on foreign mark-up (see equation 2), given that it is defined with foreign price in national currency. Instead, the only element that could change home price equilibrium (equation 1) is a variation of marginal costs. If marginal costs are increasing (C11 > 0) and both markups are constant (M1 = N1 = 0), both prices in national currency raise equal, so that PTM elasticity is equal to zero. This reflects that in that context the optimum response of export firms is to maintain the price ratio. This case shows that incomplete EPT (-1<1<0) is compatible with non price discrimination. This indicates clearly that the effect of exchange rate prices on relative prices are defined by the elasticities of margins5: though home and foreign prices may increase as consequence of marginal costs shifts, it will not affect to the price ratio. The price ratio Xt can change not only due to variations of exchange rate, but also variations of price inputs (Zt), which is the second argument of cost function. It can be obtained differentiating the first order condition as: 2 = X t Zt = ( - )C12Zt et / H C1 Zt X t If marginal costs are constant (C12=0), there is not effect of inputs cost on relative price. In other case, the impact of the variation of the input cost is proportional to the difference between the foreign and domestic margin elasticities: if both markups are identical (=), a variation in inputs price will have no effect on relative prices. Though exchange rate fluctuation is likely an important variable explaining price differential growth across foreign and home markets, it is not the only one. Other effects linked to destination markets and industry characteristics may play a relevant role. Particularly, changes in demand may generate variations in prices and, therefore, in relative prices. In fact, an expansion of home (foreign) demand referred in previous section could incorporate the effect of home (foreign) income. Income elasticities obtained would have an elaborate form, which depends on marginal costs, equilibrium prices and elasticities of markups with respect to prices and income. In that context trying to identify the predicted sign is a difficult task. 4 5 The foreign markup elasticity can be expressed as follows: = -Q Q /( - 1) . An alternative approach, not based on the convexity of demand schedules, is due to Kasa (1992), 6 Nevertheless, we can turn towards the predictions about the effects of shifts in demand on changes in prices derived from the context of industrial organization. In that field the debate about the procyclical or countercyclical character of prices and markups has given object of an abundant literature. Though some studies (as Rotemberg and Saloner (1986)) predict a countercyclical behavior, the majority empirical evidence supports a procyclical relationship. One of the reasons pointed out is that more expansive demand facilitates to get collusive agreements (Haltinwanger and Harrington (1991)). That would be certain independently of the geographic ambit of the market (home or foreign). The transmission of demand shifts to prices in each market may be affected by the degree of competition. The evidence obtained in this case is, however, not conclusive. Phlips (1980) concluded theoretically that demand changes are less transmitted into prices in industries with more firms, and found some empirical support for that proposition. That analysis was later extended by Weiss (1994) considering the another dimension in the level of concentration: the effect of disparities in firm size. In that case he obtains a non linear effect of market concentration on the sensitivity of prices to demand and cost changes. In a more recent study, Ghosal (2000) concludes that in high concentration industries markups increase with monetary expansion (the demand indicator), while it does not happen in low concentration industries. These results are agreed with previous reasoning about larger possibilities to achieve collusive agreements in expansive cycle. On the other hand, the effect of exchange rate variation on export price (and therefore in relative prices), neither is independent of the level of competition in foreign markets. From Dornbush (1987), several studies have analyzed the effects of market structure on EPT. In an oligopoly with Cournot conjectures and homogeneous product, EPT depends positively (is more complete) on: i) the percentage of export firms in foreign market related to total firms, and ii) the degree of competition. The first of those effects is a country effect, in the sense that it depends on market share of all export firms in the destiny market. With relation to the second effect, the theoretical who analyzes price discrimination across export markets based on differences in adjustment costs. 7 predictions are not conclusive. While some authors predict that a more concentrated market implies less EPT (Lee (1997), Menon (1996)), and then more PTM, other authors expect the opposite result (Knetter (1993)). Then, the effect of a given exchange rate variation on export price in national currency, and therefore on relative prices, related to the competitive environment is not clear6. 3. Empirical specification Departing from Eq. (1) and (2), a simple empirical specification in logarithmic differences is used. Price variation in each market - home and foreign - depends on two factors: changes in marginal costs (Cit) and changes in home and foreign markups (Mit and Nit, respectively). Pit* = 1F Cit + F2 Nit + itF ((3) Pit = 1H Cit + H2 Mit + itH ((4) where is the logarithmic difference, the subindex i is referred to firms (i=1,...N), t is time (t=1,...T), F and H are foreign and home markets, P*it is foreign price expressed in home currency and Pit is home price. Following previous notation, Pit* = eit + Qit . Finally, itF and itH are error terms with usual properties. Exchange rate has a subindex i now, indicating that, though it is a macroeconomic variable exogenous to firms, it should only get those variations of exchange rate that are relevant for each firm. It is to say those changes with currencies of destination countries. Our interest lies in analyzing the variation of relative prices, which is approached by the difference between (3) and (4): Xit = P*it - Pit = 1F Cit - 1H Cit F2 Nit - H2 Mit + u it ((5) where uit=itF-itH, being itF and itH uncorrelated error terms. 6 Feenstra et al. (1996) using a Bertrand differentiated products model show that pass-through decreases with market share for low market shares, but it rises at an increasing rate, as market share grows large. With small and intermediate market shares, the relationship is nonlinear and sensitive to assumptions about demand and firms interactions. 8 In equation (5) the effects of changes in marginal costs on relative prices would disappear if 1F = 1H. It may be justified in our assumption about a joint cost function. However, even if we consider that such assumption is too strong7, it would have small consequences, given that empirical specification is in first differences. We would have to assume the presence of some type of supply shock that only affected to the cost of a final destination. The differences in price variation across markets are then explained by differences in changes in markups. The empirical specification incorporating explaining variables referred in previous section is: Pit* Pit = 1 eit + 0 (comitF * eit) + 1 d itF + 2 d itH 3 ( d itF * comitF) + 4 ( d itH * comitH) + 5Zit u it 1 > 0, 0 0, 1 > 0, 2 < 0, 3 < 0, 4 > 0, 5 0 where eit is exchange rate variation, Zt is the cost variation, ditF ( d itH ) is demand variation in foreign (home) market, and comitF (comitH) is the degree of competition in foreign (home) market. As it was commented the last one appears interacting with to capture possible differences in demand and exchange rate transmission according to the degree of competition. We could think that marginal costs shifts due to input prices changes could affect to relative prices. An exchange rate fluctuation or any other reason could explain that change in input price. If our interest was to model export prices, we should take in account that a depreciation of national currency makes more expensive the imported inputs8. With industrial data, Athurokala and Menon (1994) propose a simultaneous estimation of export price and cost functions. An interesting point in the empirical model is about firm effects. It is clear that some idiosyncratic effects could underlie in Eq. (3) and (4), generating differences in the variation of 7 It could be argued that products sold in both markets are affected by different costs. Some of them would be sunk costs (i.e., costs linked to entry in foreign markets), but others would be variable costs (i.e., transport costs), so that we could think in different marginal costs affecting both prices. 8 That would be particularly relevant for Spanish economy in which, according to Input-Output Tables, about 25% of industrial inputs in 1990 were imported. 9 prices with respect to other firms. However, those effects would disappear in Eq. (5), independently whether they are or are not observable9. This fact is significant because we could think about other aspects influencing in price variations; for example, unobservable quality and reputation (Allen (1988)). However, they are fixed firm effects, which disappear as explicative variable given the empirical specification used here. This is extensive to any other firm variable which has not variability with respect to destiny market10. 4. Econometric results 4.1 Data and variables The sample is provided by the Survey on Business Strategies (SBS). This survey is carried out yearly by the Spanish Ministry of Science and Technology for about 2000 representative Spanish manufacturers (excluding the power generation plants and extractive companies). The population considered covers manufacturing firms with ten or more employees. All companies with over 200 employees were asked to participate. A second category was made up of companies that employed between 10 and 200 workers, which were selected by a random sampling scheme. The SBS industry classification and its correspondence with NACE rev.1 are detailed in Appendix. The surveyed firms give annual information about markets served, up to a maximum of five, identifying their relative importance (in percentage) in total sales of the firm. Those markets should cover at least fifty percent of total sales of the firm. Each firm identifies the geographic ambit and the variation of price (not the level) with respect to last year. The geographic ambit is defined by three categories: a) home (composing by local, provincial, regional and on a nationwide basis), b) foreign and c) home-foreign11. The percentages of firms defining each category As Aw et al. (1997) point out, if fixed firm effects i are supposed in Eq.(3) and (4), and those effects were relevant (which is in line with evidence will be showed in next section), the error variance of equation (5) ( V( u it ) = V( itF - itH ) = 2 2 ) will be smaller than error variance in each one 9 ( V( i + it ) = 2 + 2 ). It implies a more precise estimate of the differences in prices across markets that estimates using only firms selling in each one of both markets. 10 Of course, this reasoning is not extensive if the firm effect is market varying. For example, if firm reputation perceived by consumers depends on the character of the market (domestic or export). It is known that reputation acts reducing demand elasticity. 11 By survey design the firms could not define the field market as c) type in 1990 (they only could decide between a and b categories. 10 are showed in Table 1. A distinction is made between main market (which represents the largest percent of the total sales) and all markets in which firms operate. In 1991, the 78% of the firms define their main market as a domestic one. That proportion has gone down in favour of those firms whose main market is foreign or home-foreign, accomplishing the process of internationalization of Spanish firms. That proportion is also reduced when all markets (until a maximum of five) are considered. Table 1 Percentage of firms according geographical ambit (1991-1999) Main market Home Foreign 1991 78.67 1992 All markets Home Foreign 4.71 Home and foreign 16.62 73.90 11.13 Home and foreign 14.97 77.95 4.70 17.35 72.71 11.10 16.19 1993 76.57 5.40 18.03 71.45 11.94 16.62 1994 76.92 5.76 17.32 70.81 13.08 16.11 1995 72.20 6.71 21.08 66.44 13.82 19.74 1996 73.02 6.24 20.75 65.94 14.76 19.30 1997 70.00 6.82 23.18 63.35 15.04 21.60 1998 69.43 6.36 24.21 62.38 15.24 22.38 1999 68.07 6.78 25.14 61.84 14.86 23.30 Given that our main interest is to analyse price discrimination behaviour, only those firms operating simultaneously in both markets (home and foreign) have been selected. This does not generate any selection bias, but it must be stressed that the analysis implemented is only true for this type of firms. Price variation variable by destiny market (or other explicative variables) has been elaborated weighting each market in firm sales as a whole. Given that a large part of firms operate in home/foreign markets, this category has been added12. Besides, in order 12 In that case home/foreign category has been added to both home and foreign type. It implies that average value of any variable in both markets will tend to be equal for each firm. So, if firm has one 11 to assure that products sold in both markets by each firm are identical, only non-diversifying firms according to the 5-digit industrial classification have been selected13. Of course, differences in quality of products sold in each market may play a (unknown) role. The total number of observations for the period 1991-1999, after missing data for any variable have been removed, is 2346. As it is showed in Table 2, about 40 percent of manufacturing Spanish firms vary prices in a different magnitude between both markets. However, for each firm, the relation between home and foreign price variations is very close. The correlation is over 86% for all the period, and it is reduced to 74% when only firms varying prices in distinct magnitude in both markets are considered. That relation can be seen in Figure 1, in which the main line indicates the non-discriminating behaviour. An additional result that can be obtained from Figure 1 is the high dispersion of price variations among firms. This avoids comparing home and foreign markets mean price variation: the industrial variance is so high that the equality between price variation in both markets is always accepted. In other words, the disparities in the variations of prices among firms are much higher than disparities in price variations between home and foreign markets for each firm. This result emphasises that the use of industrial aggregate variations of prices hide the high differences among firms. (or several) home market, none foreign and one (or several) home/foreign market, home price variation – or any other variable defined at firm market level – will be composed by home and home/foreign, while foreign price variation is defined with home/foreign market. The opposite process is applied if the firm has not home markets, but it has foreign and home/foreign market. 13 An analysis of diversification with this survey can be seen in Merino and Rodriguez (1998). 12 Figure 1 Foreign and home prices evolution (1991-1999) 100 80 60 PVH 40 20 0 -60 -40 0 -20 20 40 60 80 100 -20 -40 -60 PVF This high variation across firms implies that when a variance decomposition analysis is done for the price differences in each industry, the industrial variability is explained by differences among firms, while the differences in price variation between markets for each firm are not significant. The result is still standing even if a less aggregated industrial classification is employed. Aw et al. (1997) get also high disparities in prices between home and exports markets in a sample of Taiwanese electronic distributed in sectors defined at seven digit classification. 13 Table 2 Price variation by markets (1991-1999) Number of firms Percentage of firms with Pvh pvf Average variation price by market Pvh Pvf 1991 267 45.3 1.44 1.42 1992 264 48.1 0.28 0.69 1993 249 40.9 1.13 1.55 1994 261 44.4 4.40 4.50 1995 253 41.5 4.46 3.85 1996 271 40.2 0.95 1.03 1997 323 39.6 1.35 1.34 1998 328 38.7 0.31 0.16 1999 315 31.4 0.54 0.62 Total 2600 41.0 1.49 1.53 Though both prices show a procyclical behaviour, in 1992-1994, 1996 and 1999 foreign prices (pvf) grew up more than home prices (pvh). The first three years coincided with the devaluation of the peseta. It is important to recall that both prices are measured as growth rates, so we really do not know if a positive difference between both prices indicates a convergence or the opposite. Given that production in foreign plants of Spanish firms is very reduced, export price is not biased by intra-firms transactions among home plant and subsidiary plants in foreign countries14. However, a 30% of surveyed firms are owned by foreign companies in a proportion over 30% percent of its capital (the simple average for all firms is 26,8%). That circumstance could generate a distinct possibility to discriminate prices between home and foreign owned firms15. 14 Rangan and Lawrence (1993) indicate to transfer pricing as the principal critique to the use of aggregate export prices to infer price discrimination. 15 Other interesting descriptive number is that more than 90% of analyzed firms have only one 14 Naturally, as Goldberg and Knetter (1997, note 7) point out, price discrimination among domestic markets could occur too. Then, the proportion of firms with distinct price variations between nation-wide basis markets and smaller ambit markets (local, provincial and regional) has been calculated for each market. Though a relevant percentage of firms seem to discriminate across home markets too, that percentage tends to stay at lower value with respect to those obtained comparing home and foreign markets16. This fact is related with evidence obtained by Engel and Rogers (1997) about the border effect on price variations. The explicative variables included are four. Firstly, a nominal exchange rate variation has been elaborated for each firm. It uses information about export destination gathered in the European Union, the rest of OECD and non-OECD countries in 1990, 1994 and 1998. That exchange rate has been elaborated in first differences, and a positive sign indicates a depreciation of home currency. Secondly, the variation of demand has been measured by a dummy variable indicating the degree of dynamism of demand in each market: dif and dih for foreign and home markets, respectively. It has three values: 1 (recessive market), 2 (steady market) and 3 (expansive market). Thirdly, the degree of competition is approached by two variables. The first one is the number of competing firms in the markets: ncf and nch for foreign and home markets, respectively. It is also a discrete variable with values: 1 (10 or less competitors), 2 (from 11 to 25 competitors), 3 (more than 25 competitors) and 4 (atomized market). The second one is the share market of the firm. A zero value is assigned to the share when the firm answers that his share is non-significant. All variables have been elaborated weighting each category of market in the same way than used previously for price variations, and the average values are showed in Table 3. Finally, Z has been approached by evolution of labour costs by worker. industrial plant. That fact makes more probable than marginal costs are equal between both types of markets. Gron and Swenson (1996) point out that a larger flexibility in production, understood as the possibility to change among plants in different countries, is associated with a lesser EPT. 16 The average percentage of firms varying prices in distinct magnitude for period 1990-1995 is 27,9% (26,8% and 29,6%) for firms selling local (provincial and regional) and nation-wide market. These results should be seen with caution because the number of observations is smaller: 212 (327 and 526) for the whole period. 15 Table 3 Average values of market dynamism, market share market and the number of competitors (1991-1999) Dih Dif Firms percent with dih=dif 2.03 2.15 39% Nch Ncf Firms percent with nch=ncf 1.71 2.04 58% Msh Msf Firms percent with msh=msf 17.88 8.67 36% Firms percent with dih=dif, nch=ncf and msh=msf 24% As it is expected, firms indicate higher level of competition and higher market dynamism in foreign markets. It is important to emphasize that these variables have been elaborated with information provided by firms. It implies that such variables pick up the effect of the relevant competition for the firms, avoiding the classical problem of the relevant market that emerges with aggregate (industrial) information. In that sense, though Spain is usually considered as a little country in the context of international trade (the Spanish market share in EU was 3,8 % in 1996) that assumption has not to be true at firm level. Each firm identifies its relevant market, so that the ambit of competition is more limited. 4.2 Estimation results The empirical model has been estimated by ordinary least squares, taking into account the usual assumptions in panel data methodology. Particularly, it has been supposed that error terms are independent among firms, but restrictions on autocovariances are not imposed for each firm (arbitrary heteroscedasticity and autocorrelation is taking into account). The results of a previous regression (not presented in text) with only temporal effects as explanatory variables shows significant differences in the variation of prices across foreign and home markets by three years: 1992, 1993 and 1995. Probably, in the early years the effects derived from the devaluation of the peseta were an important explanatory factor. In 1995 an additional devaluation happened, but it seems to have been taken over by the 16 procyclical behavior of prices in both markets, and especially by the recovery of home prices. The estimations presented in Table 4 do not include temporal effects due to they are highly multicolinear with exchange rate variations. That is because exchange rate is a macroeconomic variable whose variability among firms is the result of the distinct weighting that each export market (EU and rest of world) has in exports of the firm as a whole. In that sense the step effect introduced by exchange rate is statistically similar to temporal artificial variables. However all estimations include industrial dummies. In some of them the Wald test barely allows us to reject the null hypothesis that industrial effects are equal to zero. In columns1 and 2 the results of including only exchange rate changes, demand and cost evolution are showed. In column 2 the estimated coefficient for home and foreign demand has been restricted such as 1=-2. A positive and significant effect of the exchange rate on relative prices can be observed. The estimated coefficient reflects that a 10% devaluation of national currency raises the differential of prices between both markets by 0,4%. This effect could seem small, but two aspects should be in mind. Firstly, due to the temporal amplitude of data used (changes over one year), it can be thought that this is a long-term effect. Probably, in the short term (monthly or quarterly data) the increase in export price in home currency after a non-anticipated depreciation of national currency (and, then, in relative prices) could be more relevant due to prefixed prices if export price is invoiced in foreign currency17. As contracts are revised, it is more likely that national currency depreciation is passed through export price in foreign currency. We don’t know too much about the delivery lags to change contract prices for Spanish firms18. 17 According to the Bank of Spain, 55% of Spanish exports of products were invoiced in foreign currency in 1991. This percentage was one of the largest in EU and was similar to Japan (Marston, 1990). 18 That also happens for other countries. Kim (1990) is one of the few using delivery lag to link observed prices (in fact, unit-values) with contract prices. 17 Table 4 Differences in price variations across markets: foreign-home (1991-1999). e 1 0.037 (1.9) 2 0.035 (1.8) 3 0.040 (2.1) 0.403 (3.4) 0.004 (5.3) -0.268 (2.1) -0.003 (3.9) 4 0.034 (1.8) 0.0006 (1.5) 0.408 (3.5) 0.004 (4.3) -0.261 (2.1) -0.004 (4.3) 0.002 (0.6) 0.412 (3.6) 0.002 (0.6) 0.002 (0.4) 0.002 (0.4) 2346 2346 2346 2346 e x comF x p* dF 0.454 (3.6) dF x comF x p* dH -0.359 (2.7) dH x comH x p dF-dH z Number of Observations 5 0.034 (1.9) 0.0004 (1.2) 0.354 (3.2) 0.004 (5.1) -0.238 (2.1) -0.003 (5.1) 2600 Industrial effects 35.3 42.9 28.9 28.7 29.9 Notes: T-ratios robust to heteroscedasticity in parentheses. Joint significant of industrial effects is calculated with a Wald test robust to heteroscedasticity. Secondly, the empirical specification used eliminates all effects determining price variations with independence of the destiny market. The clearest example is raw material price variations, which is the main cause alleged by firms to justify large price variations. In fact, cost variation shows non-significant results. With respect to demand evolution, the significant positive sign obtained in demand evolution variable shows that a more expansive foreign market (in relation to home market) implies a higher rise in foreign price (in relation to home market again). When both variables are considered separately, there is a small larger of foreign demand growth on relative prices comparing to home demand (in absolute value). 18 The results presented approach the degree of competition by the market share of firms. Complementary regressions including the number of competitors give the same results (of course, with opposite sign). The results obtained in relation to the degree of competition in both markets are satisfactory with respect to previous hypothesis. The interaction between market dynamism and the market share, presented in column 3, suggests that a larger market power lets larger transmission of demand changes to prices in both markets. This result is according to previous empirical research. With respect to the interaction between exchange rate and the degree of competition, the obtained coefficient is positive, indicating larger PTM (an then larger price stabilisation in foreign markets) is related to larger market power, though is not significant. The results show that there is not a significant effect of cost variation on relative prices. For that reason, we drop that variable in column 5, expanding the considered period to 1990 and founding the same results as previous regressions. There are some factors that could condition larger possibilities to vary prices in different magnitude across markets. Firstly, firms using owned export channels could have more opportunities to discriminate among markets. A similar result would be hoped with respect to foreign owned firms. Secondly, the oriented foreign trade of the firm could have more incentives to discriminate, given that the export market would be a relevant market for those firms. In complementary regressions those effects were introduced, but the results were not significant. This fact emphasizes the difficulty to explain the differences in price variation across firms departing from variables that do not distinguish among markets. An explanation about the small parameter of PTM elasticity lies on the length of covered period, where exchange rate variations are small in several years. It seems reasonable to think that PTM strategy, which implies price stabilisation in export markets, is more probable in periods of relevant exchange rate variations. Note that in last years of the period (1998-1999), the entry in the third phase of European Monetary Union implied a flat variation of domestic currency with respect to the participants’ countries, which are the main destiny of Spanish exports. For that reason we have repeated the estimations in Table 4 for the reduced period 1993- 19 1995. They are showed in Table 5. As can be seen, the economic implications of results are the same of those obtained for all period. However, the PTM elasticity is substantially larger. A home currency depreciation of 10% implies in this period an increase in the relative prices about 1%. It seems that Spanish export firms used the devaluations in 1993/1994 to increase margins in the foreign markets. Table 5 Differences in price variations across markets: foreign-home (1993-1995) e 1 0.100 (3.4) e x comF x p* dF dF x comF x p* dH dH x comH x p dF-dH 2 0.105 (3.6) 0.0003 (0.9) 0.604 (2.6) 0.002 (2.4) -0.210 (0.8) -0.002 (2.3) 3 0.097 (3.4) 0.0003 (1.2) 0.528 (2.4) 0.002 (2.6) -0.196 (0.8) -0.002 (2.5) 0.469 (2.1) 0.004 (0.3) 0.004 (0.3) Number of Observations 714 714 763 Industrial effects 43.0 39.6 37.4 z Notes: T-ratios robust to heteroscedasticity in parentheses. Joint significant of industrial effects is calculated with a Wald test robust to heteroscedasticity. 20 5.- Conclusions. This paper has tried to contribute to fill the gap of empirical approaches with firm data in PTM literature context, explaining price discriminating behavior across foreign and home markets for Spanish manufacturing firms. Though the main goal has been to evaluate the effect of exchange rate variation on relative (foreign/home) prices, the impact of other explicative factors have been considered too. In fact, Industrial Economics analyze topics related with central questions in PTM literature: causes of non-response price, contracts or costs of adjustments, etc. The empirical approach used in this paper is similar to Knetter´s model. He tries to control price variations due to changes in marginal costs, so that he obtains those price variations related with changes in markup specific by destiny market. In this paper, the availability of firm data allows us to observe the differences in prices across foreign and home markets, so that mainly those effects related with differences in markups variations across markets are considered. The PTM elasticity obtained for the period 1990-1999, though significantly different of zero, is small. This fact contrast with large elasticities in studies such as Marston (1990) for Japan firms. It can be due to several reasons. Firstly, as it has been indicated before, empirical studies try to control the effect of unanticipated changes in the exchange rate. However, it is possible that the methods applied - which usually are very dependent on assumptions about the distribution of the exchange rate and the timing of prefixed prices- do not allow to avoid the observed growth in relative prices when export prices are prefixed in foreign currency. This problem is more pressing given that usually the structure of delaying contracts is not known. To the contrary, the ample period used here (annual data) allow us to avoid in large part that amplified bias on PTM elasticity. Secondly, the analyzed period is characterized by national currency depreciation. Then, given the nature of the European Monetary System, the probability that a Spanish export would perceive the exchange rate of the peseta against other European currencies as a temporary change should not be large. Therefore, export firms will have lesser incentives to delay its response after 21 exchange rate depreciation. It would imply a larger EPT and, then, a lesser effect of exchange rate variation on relative prices. When the estimations are repeated for a shorter period, 1993-1995, just including the years of the Spanish devaluation, we found a larger PTM elasticity. For this period, a 10% devaluation of the peseta raises the differential of prices between both markets by 1%. The fact than in a small country as Spain, export firms have a discriminate pricing behavior is not a surprising result. The existence of incomplete EPT, yet in small countries, is a well-established result in the literature (i.e., Buguin, 1996, for Belgian firms). It is a reality than in EU important price differences not due to fiscal causes remain. A known example is the market for automobiles. However, the obtained results indicate that price discrimination seems to be independent of some firm characteristics. Particularly, export propensity or using owned channels to access foreign markets do not seem to exert a significant influence. Contrary to the case analyzed by Aw et al. (2001), changes in institutional context should not have exercised a significant influence on the obtained evidence. The removal of tariff barriers and other trade restrictions against other European countries after entrance in EU (then EEC) had almost been completed in 1990. Besides, though the implementation of the Single European Market from 1987 to 1993 eliminated non-tariff trade barriers among European countries, the effect on prices would affect in both markets (home and markets) in similar ways. 22 References: Allen, F. (1988): "A Theory of Price Rigidities when Quality is Unobservable", Review of Economic Studies 55, pp. 139-151. Athukorala, P. and Menon, J. (1994): "Pricing to market behaviour and exchange rate passthrough in japanese exports", The Economic Journal 104, pp. 271-281. Aw, B.Y., Batra, G. and Roberts, M.J. (2001): "Firm Heterogeneity and Export-Domestic Price Differentials: A Study of Taiwanese Electronics Products", Journal of International Economics, 54, pp. 149-169. Dornbush, R. (1987): "Exchange Rates and Prices", American Economic Review 77, pp. 93-106. Engel, C. and Rogers, J.H. (1996): “How wide is the border?”, American Economic Review 86, pp. 1112-1125 Feenstra, R.C, Gagnon, J.E. and Knetter, M.M. (1996): "Market share and exchange rate passthrough in world automobile trade", Journal of International Economics 40, pp. 187-207. Gagnon, J.E. and Knetter, M. (1994): "Pricing to market in international trade: Evidence from panel data on automobiles", Journal of International Money and Finance 14, pp. 289310. Ghosal, V. (2000): “Product market competition and the industry price-cost markup fluctuations: Role of energy price and monetary changes”, International Journal of Industrial Organization 18(3), pp. 415-444. Giovannini, A. (1988): “Exchange rate and traded good prices”, Journal of International Economics 24, pp. 45-68. Goldberg, P. and Knetter, M. (1997): "Goods Prices and Exchange Rates: What Have We Learned?", Journal of Economic Literature 35, pp. 1243-1272. Gron, A. and Swenson, D.L. (1996): "Incomplete Exchange-Rate Pass Through and Imperfect Competition: The Effect of Local Production", The American Economic Review 86, pp. 71-76. Haltinwanger, J. and Harrington, J. (1991):”The impact of cyclical demand movements on collusive behavior”, RAND Journal of Economics 22, pp. 89-106 Kadiyali, V. (1997): “Exchange rate pass-through for strategic pricing and advertising: An empirical analysis of U.S. photographic film industry”, Journal of International Economics 43, pp. 437-461. Kasa, K. (1992): "Adjustment costs and pricing-to-market. Theory and evidence", Journal of International Economics 32, pp. 1-30. 23 Kim, Y. (1990): "Exchange Rates and Import Prices in the United States: A Varying Parameter Estimation of Exchange-Rate Pass-Through", Journal of Busines & Economic Statistics 8, pp. 305-314. Knetter, M. (1989): "Price discrimination by U.S. and German exporters", American Economic Review 79, pp. 198-210. Knetter, M. (1993): "The international comparison of price-to-market behavior", American Economic Review 83, pp. 473-486. Krugman, P. (1987): "Pricing to market when the exchange rate changes", in S.W. Arndt and J.D. Richardson (eds.), Real-financial linkages among open economies, MIT Press, Cambridge. Lee, J. (1997): "The response of exchange rate pass-through to market concentration in a small economy: the evidence from Korea", The Review of Economics and Statistics 79, pp. 142-145. Lipsey, R.E, Molinari, L. and Kravis, I.B. (1991): "Measures of Prices and Prices Competitiviness in International Trade in Manufactured Goods", in P. Hooper and J.D. Richardson (eds.), International Economics Transactions, Issues in Measurement and Empirical Research, University of Chicago Press, pp. 144-195 Marston, R. (1990): "Pricing to market in Japanese manufacturing", Journal of International Economics 29, pp. 217-236. Menon, J. (1995): "Exchange rate pass-through", Journal of Economic Surveys 9, pp. 197-231. Menon, J. (1996): "The degree of the determinants of exchange rate pass-through: market structure, no-tariff barriers and multinational corporations", The Economic Journal, 106, pp. 434-444. Merino, F. and Rodríguez, D. (1997): “A consistent analysis of diversification with nonobservable firm effects”, Strategic Management Journal 18(9), pp. 733-744. Phlips, L. (1980): "Intertemporal Price Discrimination and Sticky Prices", The Quarterly Journal of Economics 95, pp. 525-542. Rangan, S. and Lawrence, R.Z. (1993): "The Responses of U.S. Firms to Exchange Rate Fluctuations: Piercing the Corporate Veil", Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 2, pp. 341-369. Rotemberg, J. and Saloner, G. (1986): “A supergame-theoretic model of price wars during booms”, American Economic Review 70, pp. 390-407. Weiss, C.R. (1994): "Market Structure and Pricing Behaviour in Austrian Manufacturing", in K. Aiginger and J. Finsinger (eds.): Applied Industrial Organization, pp. 187-203. 24