Teaching Phrasal Verbs to Lower Learners

1

LSA 1

Helping lower level learners understand and use phrasal verbs.

Simon Richardson

Word Count: 2494

2

Contents

Introduction

Analysis of Phrasal Verbs

Learner Problems and Solutions for Teachers

Conclusion

Bibliography

Appendices

1) New Cutting Edge Intermediate, Cunningham and Moor, P.78

2) Adapted from Teaching Collocation: Further

Developments in the Lexical Approach, Lewis, P.45

Page 3

Page 3

Page 7

Page 12

Page 13

Page 14

3

Introduction

Learners of English have problems with phrasal verbs as they are not singular in part, can take different forms and have levels of idiomaticity. This causes significant comprehension issues, particularly for lower level learners, who will have encountered prepositions of place and time and are less comfortable with processing language in lexical chunks. I am not satisfied that the way phrasal verbs are approached in course books and in the classroom is appropriate for the learner, as they are often separated, leading to confusion. As a result, learners are often not only afraid to use phrasal verbs, limiting their vocabulary accordingly, but they do not recognise them, as they habitually process words individually, something that I have observed being the case in my own classroom experience. For these reasons, I have decided to limit my scope to A1-B1 (Elementary – Mid-Intermediate) learners in order to focus on how phrasal verbs should be presented so as to make them easier to understand, process and use.

Analysis of Phrasal Verbs

Meaning and Use

To begin with, it is important to present a clear definition of what a phrasal verb is. Dave Willis cites Nattinger and DeCarricio in defining a phrasal verb as a variation of ‘polyword’ (multi-word verb) that often has a singular equivalent

(Nattinger and Decarricio in Willis, 2009). I feel that viewing a phrasal verb as a polyword is a useful one, as the connotative meaning of this clearly implies that it is a singular piece of vocabulary, rather than a dividable lexical item. Looking at a range of phrasal verbs allows us to see that there are clear degrees of meaning. Thornbury labels these as literal, semi-idiomatic and very idiomatic (Thornbury, 2002, P.116).

4

Clearly this is an important observation, and it is true that phrasal verbs can communicate a literal meaning, where the individual meanings of the verb and particle remain intact, in contrast with other phrasal verbs that carry a completed altered, idiomatic meaning. However, semi-idiomaticity does also exist, in which the phrasal verb retains the literal notion implied by the action of the verb and the direction of the preposition, although there is only conceptual movement or direction in the context.

Meaning

Literal meaning.

E.g. Put the cup down over there. The speaker is asking the listener to place the cup on something.

Semi-idiomaticity.

E.g. The comedian put down the heckler. There is a notional idea of direction, as the verbal action of a putdown is to lower the status of somebody else. However, there is no physical change.

Full idiomaticity

E.g. We had to have the dog put down. The dog has been injected so as to kill it, because of its being in poor health. There is no physical or notional idea of direction that might give learners a clue as to the meaning.

5

Use

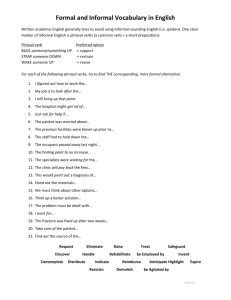

While it is the case that phrasal verbs are used with a higher frequency in spoken English than in written, it is not appropriate to attribute informality to phrasal verbs as a whole. Indeed, while a lot of phrasal verbs do have single verb close equivalents in meaning, some do not and would be used in academic essays.

Furthermore, context plays a role in deciding the appropriacy or formality of a phrasal verb. Consider the following:

Change in appropriacy dependent on context

E.g. ‘ …these studies… are largely based on self-description’

(http://www.newscientist.com/article/mg21428590.200-political-divides-begin-in-thebrain.html, 2012) The phrasal verb is appropriate in a formal context and there is no satisfactory alternative.

E.g. II

“Based on what??”

A challenge to an idea or decision that could be seen as aggressive or rude. A polite alternative is available (“Could you explain the basis of your decision, please?”)

Colloquial, regardless of context

E.g. “I think I’m going to throw up”. The speaker is replacing ‘be sick’ with a colloquial term here. This would not be considered appropriate in polite company.

Appropriacy dependent on status

E.g.

“I rocked up at ten o’clock”

An employee would be being inappropriate using the phrasal verb here. “Arrive” would be appropriate language.

6

E.g. II

“You can’t just rock up at 10 o’clock and expect everything to be OK”

In this situation, an employer is highlighting a lack of punctuality in a disciplinary situation, which would be considered formal. However, the language used here is appropriate.

Form

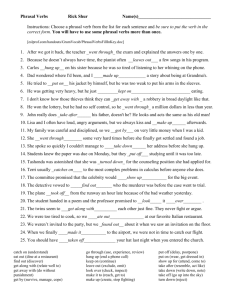

Phrasal verbs are formed with a verb followed by a particle (adverb or preposition). The verb tense is alterable, whereas changing the preposition either creates a new phrasal verb with a different meaning, or presents an impossible combination with no meaning. Phrasal verbs can be two or three part, the latter having two particles. In addition, they can be separable or inseparable.

Phrasal Verb

Type

1) Transitive, separable

2) Transitive, inseparable

Example

1) He put the pen down

2) He put down the pen

3) He put it down

1) He looked at the girl

2) He looked at her

Comments

With transitive separable phrasal verbs, the verb and particle are separated when a pronoun replaces a direct object. The object or pronoun can not appear before the verb.

As above, the phrasal verb requires a direct object or pronoun, but these appear after the particle.

3) Intransitive 1) The storm blew over

No object is taken with this type of phrasal verb.

1) I get on with him As with 2. 4) Three-part

(transitive, inseparable)

Phonology

Phrasal verbs carry stress at sentence level, as do single word verbs. They are pronounced as one word when the particle begins with a vowel. In the case of intransitive phrasal verbs, the particle carries the stress regardless of this join.

E.g. “When do you get up?” becomes /ˌwenʤ gedˈʊp/

7

However, with transitive, inseparable phrasal verbs, the verb carries the stress and the particle is unstressed.

E.g. “He looked at the girl” becomes /hɪ ˌlʊktəʔ ðəˈgɜ:l/

In the above instance the object also carries stress, but this is not the case if there is an object pronoun. This becomes important with transitive, separable phrasal verbs, as a pronoun between the verb and particle results in the verb and particle both carrying stress, where an object between the verb and particle results in the particle being unstressed.

E.g. “He turned the light on” becomes /hɪ ˈtɜ:nd ðəˌlaɪtɒn/ , whereas “He turned it on” becomes /hɪ ˌtɜ:ndɪʔˈɒn/

Learner Problems and Solutions for Teachers

Meaning and Use

As phrasal verbs do not appear in a lot of other languages, learners can fail to notice them, rather assuming that the meaning of each part is literal, leading to a mistranslation of phrasal verbs that have a level of idiomaticity. It is important to introduce the idea of lexis appearing as ‘chunks’ rather than individual items. Michael

Lewis writes that ‘The reason learners find unseen reading so difficult is because they don’t recognise the chunks – they read every word as if it were separate from every other word…’ (Lewis, 2000, P.56) I believe this problem is exacerbated by course books not introducing phrasal verbs early enough, meaning that learners are unfamiliar with them and can not recognise them in intermediate level texts, where they may be semi or completely idiomatic. Scott Thornbury states that ‘The ability to deploy a wide range of lexical chunks…distinguishes advanced learners from

8 intermediate ones.’ (Thornbury, 2002, P.116). He goes on to divide the factors that make up ‘lexical competence’ in to frequent exposure, opportunities to memorise and consciousness-raising. However, I believe that this idea could be altered if learners were introduced to the principles of recognising and recording lexis in chunks from an

Elementary level. Further to this, the existence of these levels of idiomaticity leads me to believe that, while it is useful for teachers to be aware of, learners would perhaps benefit from understanding that phrasal verbs, as polywords, are all idiomatic, regardless of whether they could be literally translated. Clearly, there can be a problem when a learner encounters a familiar phrasal verb, but with a different meaning. E.g. “He put the pen down” is different from “He put the dog down”.

Therefore, learners also need to be aware that phrasal verbs, as well as having more than one part, can have more than one meaning. This could also be introduced through a text in which the same phrasal verb appears multiply, and learners are encouraged to either match definitions or replace the phrasal verbs with synonyms.

In Approaches and Methods in Language Teaching, Richards and Rodgers describe an approach known as ‘The Lexical Approach’ in which lexis becomes the primary focus of a lesson, with new vocabulary being stored as a lexical unit. This idea is explored by Michael Lewis, who writes about lexical notebooks as a way of recording vocabulary in chunks. Doing this encourages learners to look at language syntactically (as part of a sentence), but Lewis also notes that ‘they need to be organised in some way’ (Lewis, 2000, P.43). Bearing this in mind, it is important not only to introduce learners to the concept of recording lexical chunks, but also to group these lexical chunks in to contexts, situations or themes. I feel that this would be more beneficial than paradigmatic grouping, in which learners record long lists of cohyponymous nouns, as they are then being encouraged to think in terms of real-life

9 situations. Gairns and Redman refer to this, stating that ‘…teaching a set of idioms that are notionally related – such as idioms associated with parts of the body…would seem to be a sure recipe for confusion’ (Thornbury, 2002, P.127) Furthermore, recording larger chunks allows learners to focus more on the variety of objects that collocate with phrasal verbs. I feel this is something that is not addressed appropriately in course books. An example of this can be seen in New Cutting Edge

Intermediate, where a ‘Wordspot’ exercise encourages learners to focus on a delexicalised verb. Some of the focus is appropriate, but the phrasal verb section of the focus merely lists some different particles that can attach to the verb, creating a phrasal verb, rather than addressing object or meaning. (Appendix 1) To address the distinction between this method of recording and the lexical notebook method, I have outlined the suggested format for a lexical notebook entry in Appendix 2. New learners at low level should be introduced to this method from day 1, as it will become a fossilised method of recording vocabulary, allowing them to achieve

Thornbury’s idea of lexical competence more quickly.

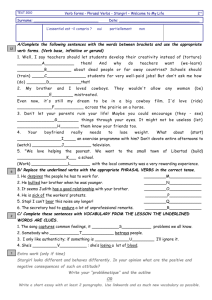

In the language classroom, introducing new lexis to lower level learners can be done effectively using a ‘language from a text’ method. This would be particularly effective, as language is presented authentically and within a sentence, allowing for effective chunking. It is also an inductive method, therefore allowing learners to

‘notice’ new lexis and its form. A text is presented to learners with sentences containing new lexical items highlighted to promote noticing, and they are encouraged to recognise the form and deduce the meaning. Meaning can be checked with a definition matching exercise (sentential, rather than focussed solely on the phrasal verb), and form can be checked with questions that refer directly to the distinction between transitive and intransitive verbs: “Is there an object?” Controlled

10 practice involves completing sentences or gap fills using sentences from the original text. This can be followed by a freer practice, where learners are encouraged to respond to questions containing the phrasal verbs. Viewing phrasal verbs as part of larger lexical chunks can yield vital information about the meaning and use, while also demonstrating the appropriacy or formality of the item. In addition, the ‘language from a text’ approach allows a teacher to appropriately select material according to level, making this appropriate for all lower levels.

Form

With inseparable phrasal verbs, it is easy for learners to recognise them once they have been introduced to the existence of the verb + particle form, but as we have already discovered, not all phrasal verbs are inseparable. A problem for learners can be that they find a phrasal verb more difficult to realise the further away the particle is from the verb in a sentence.

E.g. “

Put the pen down

” is easier to recognise than “He dropped the next-door neighbour’s children off

”

While the latter example is less common, it is a possibility in written and spoken language, which would cause difficulty for the learner. Clearly then, learners need to be made aware that some phrasal verbs can be separated, while others can not.

Separability can be effectively shown through sentence jumble and remodelling exercises. I would present these as kinaesthetic activities; learners are presented with sentences that have been cut up in to individual words and are asked to either order them or remodel an existing sentence (displayed on the whiteboard). Alternatively, learners could be asked to complete an exercise where each new lexical item is placed in to three or four sentences and they have to decide whether the sentences are correct

11 or incorrect. I would include the question after each item: “So, can we split this phrasal verb?” This question alone is effective, as it draws learners’ attention to the idea of separable and inseparable, something they should be encouraged to record in their lexical notebooks.

Phonology

In terms of pronunciation, lexis is often dealt with on a word-by-word basis, but this would be counter-intuitive when teaching language in chunks. Learners may find difficulty locating and producing correct stress on polywords, but if the teaching of stress in general is sentential rather than word-level, then learners can become aware that a phrasal verb always carries stress within a sentence, which is a useful starting point. A useful exercise for this involves learners marking stress on sentences and beating it out as they read the sentence aloud. This gives a very clear indication of the stress-timed nature of the English language, which may be a very difficult skill for learners with a syllable-timed L1 (Spanish, for example). It also encourages learners to notice the recurring stress patterns of separable and inseparable phrasal verbs. An example is as follows:

“When do you get up in the morning?”

He jumped at the chance to go fishing

I believe that rhythmic drilling aids understanding as well as fluency, as it encourages learners not only to focus on natural stress, but also to prioritise ‘important’ words as those which carry more meaning.

12

Conclusion

In carrying out research for this assignment, I have decided that phrasal verbs should not be hidden from lower level learners. Rather, they should be taught as they occur alongside singular words as part of lexis, and that lexis as a whole should be taught and recorded in lexical chunks. My future teaching of this area of the language will definitely reflect this, as well as the principle of drawing learners’ attention to the fact that polywords all carry a certain level of idiomaticity, meaning that they should be looked at contextually rather than as individual words.

13

Bibliography

Lewis, M. 2000, Teaching Collocation, Heinle

Richards, J.C and Rodgers, T.S. 2012, Approaches and Methods in Language

Teaching, Cambridge University Press

Thornbury, S. 2002, How to Teach Vocabulary, Pearson Longman

Willis, D. 2009, Rules, Patterns and Words, Cambridge University Press

Materials

Cunningham, S and Moor, P. 2011, New Cutting Edge Intermediate, Pearson

Longman

14

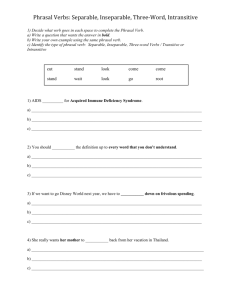

Appendix 2

Format for a lexical notebook entry

PHRASAL VERB

(pronunciation and translation)

Meaning (in English)

Example sentence

Nouns / Adjectives that collocate with the phrasal verb

G: Grammatical information (separability, form after collocative noun)

F: Favourites (Learner likes / is likely to use these sentences or chunks)

Working Example (Spanish learner)

Take your clothes off

/ˈteɪk jə ˌkləʊðzɒf/ - Quitarte su ropa

Meaning: Remove what you are wearing.

E.g. He took his clothes off before bed.

Nouns: Hat, shirt, tie (items of clothing) Adverbs: Slowly / quickly

Grammar: Can split: He took his hat off / He took off his hat

Favourites: Wait, while I take my clothes off… Take off your clothes!... I need to take these off so I can pay for them.