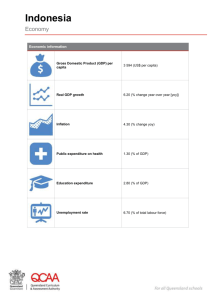

1. Health status in Indonesia.

advertisement