Training Requirements for Interpersonal Psychotherapy

advertisement

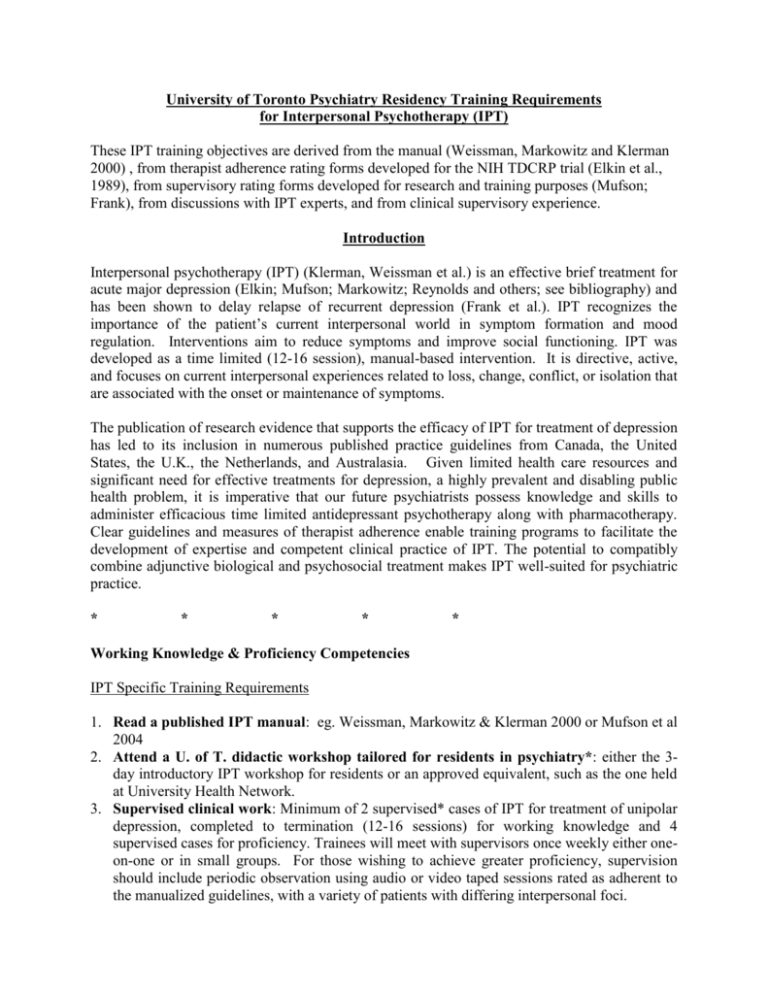

University of Toronto Psychiatry Residency Training Requirements for Interpersonal Psychotherapy (IPT) These IPT training objectives are derived from the manual (Weissman, Markowitz and Klerman 2000) , from therapist adherence rating forms developed for the NIH TDCRP trial (Elkin et al., 1989), from supervisory rating forms developed for research and training purposes (Mufson; Frank), from discussions with IPT experts, and from clinical supervisory experience. Introduction Interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT) (Klerman, Weissman et al.) is an effective brief treatment for acute major depression (Elkin; Mufson; Markowitz; Reynolds and others; see bibliography) and has been shown to delay relapse of recurrent depression (Frank et al.). IPT recognizes the importance of the patient’s current interpersonal world in symptom formation and mood regulation. Interventions aim to reduce symptoms and improve social functioning. IPT was developed as a time limited (12-16 session), manual-based intervention. It is directive, active, and focuses on current interpersonal experiences related to loss, change, conflict, or isolation that are associated with the onset or maintenance of symptoms. The publication of research evidence that supports the efficacy of IPT for treatment of depression has led to its inclusion in numerous published practice guidelines from Canada, the United States, the U.K., the Netherlands, and Australasia. Given limited health care resources and significant need for effective treatments for depression, a highly prevalent and disabling public health problem, it is imperative that our future psychiatrists possess knowledge and skills to administer efficacious time limited antidepressant psychotherapy along with pharmacotherapy. Clear guidelines and measures of therapist adherence enable training programs to facilitate the development of expertise and competent clinical practice of IPT. The potential to compatibly combine adjunctive biological and psychosocial treatment makes IPT well-suited for psychiatric practice. * * * * * Working Knowledge & Proficiency Competencies IPT Specific Training Requirements 1. Read a published IPT manual: eg. Weissman, Markowitz & Klerman 2000 or Mufson et al 2004 2. Attend a U. of T. didactic workshop tailored for residents in psychiatry*: either the 3day introductory IPT workshop for residents or an approved equivalent, such as the one held at University Health Network. 3. Supervised clinical work: Minimum of 2 supervised* cases of IPT for treatment of unipolar depression, completed to termination (12-16 sessions) for working knowledge and 4 supervised cases for proficiency. Trainees will meet with supervisors once weekly either oneon-one or in small groups. For those wishing to achieve greater proficiency, supervision should include periodic observation using audio or video taped sessions rated as adherent to the manualized guidelines, with a variety of patients with differing interpersonal foci. 4. Additional proficiency requirements: Write up a case formulation according to the IPT model. Plus one can optionally: participate in weekly CAMH IPT Clinic Rounds, attend additional group supervision sessions, co-lead an IPT group or participate in IPT research. 5. Membership in the International Society of Interpersonal Therapy (ISIPT: www.interpersonalpsychotherapy.org) and attendance of additional workshops (e.g. Dr. John Markowitz, Dr. Laura Mufson, Dr. Scott Stuart), conferences (ISIPT) or IPT presentations at other scientific conferences (CPA; APA) is encouraged. *Supervisors and faculty teaching didactic workshops must be approved by the Interpersonal Therapy Subcommittee It is expected that residents will acquire psychodynamic & general therapeutic foundational competence through additional training during the residency that enables development of ‘common-factor’ skills required to: establish and maintain a therapeutic alliance, with respectful, empathic engagement, ethical practice, upholding the responsibilities and limits of confidentiality and maintaining professional boundaries. In addition, it is expected that residents will receive psychodynamic training to develop their ability to recognize and work through counter transference issues that arise. If there are alliance ruptures, it is expected that residents will utilize a dynamically informed, yet interpersonal approach, to understand and repair them. In specific, IPT trainees will be expected to achieve changes in knowledge, and skills as specified below. Knowledge Following training, the resident will exhibit a working knowledge of IPT for treatment of depression. They will also be familiar with the background, rationale, and landmark studies that provide evidence to support the efficacy of IPT. Following training, the resident will know the therapeutic tasks performed during the beginning, middle and termination phases of therapy. These include knowledge of: diagnostic assessment and suitability criteria; the symptoms of depression; the interpersonal and bio-psycho-social understanding of depression, its epidemiology, morbidity and disabling social impact; the guidelines for when to combine pharmacotherapy with IPT; an individually tailored interpersonal formulation of depression derived from the patient’s HPI and interpersonal inventory; the interpersonal conceptualization of the sick role; the principles of the four interpersonal problem areas along with their associated goals and strategies as articulated in the manual and the therapeutic importance and tasks of termination. Skills Following training the resident will be able to perform IPT for treatment of uncomplicated depression, adhering to the manualized guidelines at the same time as maintaining the therapeutic alliance with appropriate boundaries. Consistent and active use of IPT formulation, focus, & framework working with affectively charged material derived from recent or current relationships and 2 interactions/events, demonstrating the capacity to link symptoms explicitly to interpersonal events, losses, conflict or isolation. Conduct an Interpersonal Inventory: explore interpersonal experiences with significant others, including expectations, needs, wishes, satisfaction and desired changes in recent and present relationships, impact of relationships on mood and mood on relationships. Develop and discuss with patient an interpersonal formulation of depression as a medical illness that occurs in a social context. Use the IPT conceptualization of a limited sick role, acknowledging disabling impact and encouraging the patient to utilize their social support network and to actively work towards recovery Relate depressive symptoms to focal interpersonal problem area(s): role transition, bereavement, disputes or deficits. Demonstrate capacity to relate depressive symptoms to 1-2 interpersonal problem areas. Utilize focus specific IPT strategies as applied to recent or current significant relationships in which there have been changes, loss or conflict associated with the onset or perpetuation of depressive symptoms. For the focal area of deficits, more remotely significant relationships or the therapeutic relationship are explored, attempting to identify dysfunctional interpersonal patterns & initiate more adaptive interpersonal behaviors. Recognize and use the reporting of specific interpersonal interactions to explore expectations, feelings, communication and options for change. Conduct communication analyses and role play as needed. Examine relationship expectations and communication to work through problem areas and assist in the development & more effective use of social supports through an expanded interpersonal behavioural repertoire. Empathic responsiveness and clear expression of emotions, wishes and needs are encouraged. Facilitate interpersonal problem solving through decisional analysis. 3 Appendix 1 INTERPERSONAL PSYCHOTHERAPY EVALUATION CHECKLIST For a Working Knowledge Level: 1. Socializes the patient to the IPT model and understanding of depression as a medical illness within the social context 2. Develops an interpersonal case conceptualization integrating data collected from the HPI and interpersonal inventory to choose an interpersonal focus for the therapy. 3. Establishes and maintains an effective therapeutic alliance with clear setting of goals to remit symptoms, improve social supports and resolve agreed upon interpersonal problem areas. 4. Regularly tracks symptoms & links mood with interpersonal interactions and problems 5. Uses communication analyses to both identify and work on interpersonal problems. For Proficiency Level: The five objectives above (Working Knowledge), plus: 6. Uses role-plays to explore and expand patient’s interpersonal perspective and understanding of options related to communication/relationships. 7. Links clinical material that patient brings in with the agreed upon focus, while evolving the interpersonal formulation. 8. Actively uses focus specific (i.e. disputes, transitions, bereavement, deficits) therapeutic techniques to work through problem areas 9. Assists patients to develop and more effectively use social supports 10. Performs the tasks of termination – exploring patient’s feelings about ending therapy, consolidating gains, contingency planning; or applies clinical understanding of patient to decide to extend therapy with a clear discussion of this. 4 Appendix 2: Abridged References 2006 IPT for Treatment of Depression Bolton P, Bass J, Neugebauer R, Verdeli H, Clougherty KF, Wickramaratne P, Speelman L et al. Group interpersonal psychotherapy for depression in rural Uganda – a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2003; 289: 3117-24. Browne G, Steiner M, Roberts J, Gafini A, Byrne C, Dunn E et al. Sertraline and/or interpersonal psychotherapy for patients with dysthymic disorder in primary care: 6-month comparison with longitudinal 2-year follow-up of effectiveness and costs. J Affect Disord 2002; 68: 31720. Elkin I, Shea MR, Watkins JT, Imber SD, Sotsky SM, Collins JF et al. National Institute of Mental Health treatment of depression collaborative research program: general effectiveness of treatments. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1989; 46: 971-82. Cutler, J. L., Goldyne, A., Markowitz, J. C., Devlin, M. J., & Glick, R. A. (2004). Comparing cognitive behavioral therapy, interpersonal psychotherapy, and psychodynamic psychotherapy. American Journal of Psychiatry, 161(9), 1567-1573. Cyranowski, J.M., Bookwala, J., Feske, U., Houck, P., Pilkonis, P., Kostelnik, B. and Frank, E. Adult attachment profiles, interpersonal difficulties, and response to interpersonal psychotherapy in women with recurrent major depression. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 21:191-217, 2002. Frank, Kupfer DJ, Perel JM, Cornes C, Jarrett DB, Mallinger AG et al. Three year outcomes for maintenance therapies in recurrent depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1990; 47: 1093-9. Frank, E., Kupfer, D.J., Thase, M.E., Mallinger, A.G., Swartz, H., Fagiolini, A.M., Grochocinski, V., Houck, P., Scott, J., Thompson, W. and Monk, T. Two year outcomes for interpersonal and social rhythm therapy in individuals with bipolar I disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62:996-1004, 2005. Klerman GL, Weissman MM, Rounsaville BJ, Chevron ES. Interpersonal psychotherapy of depression. New York: Basic Books; 1984. Klein DF, Ross DC. Reanalysis of the National Institute of Mental Health Treatment of Depression Collaborative Research Program general effectiveness report. Neuropsychopharmacology 1993; 8: 241-51. Markowitz JC, Kocsis JH, Fishman B, Spielman LA, Jacobsberg LB, Frances AJ et al. Treatment of HIV-positive patients with depressive symptoms. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1999; 55: 452-7. Mufson L, Weissman MM, Moreau RG. Efficacy of interpersonal psychotherapy with depressed adolescents. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1999; 56: 573-9. Mufson L, Dorta K P, Wickramaratne P, Nomura Y, Olfson M, Weissman MM. A randomized effectiveness trial of interpersonal psychotherapy for depressed adolescents. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2004; 61: 577-584 Mufson L, Pollack DK, Moreau D, Weissman MM. Interpersonal psychotherapy for depressed adolescents. Second edition. New York: Guilford Press; 2004. O’Hara MW, Stuart S, Lorman L, Wenzel A. Efficacy of interpersonal psychotherapy for postpartum depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2000; 57: 1039-45. Stuart S, Robertson M. Interpersonal psychotherapy: a clinician’s guide. London: Arnold; 2003. Weissman MM, Markowitz JW, Klerman GL. Comprehensive guide to interpersonal psychotherapy. New York: Basic Books; 2000. *For a full IPT Bibliography contact either Dr. Paula Ravitz (paula_ravitz@camh.net or Liz Konigshaus at lkonigshaus@mtsinai.on.ca) 5