handout

advertisement

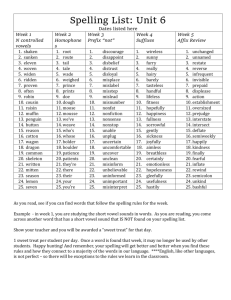

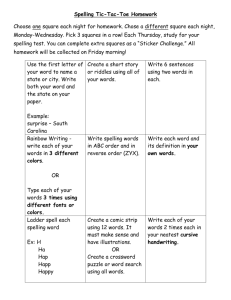

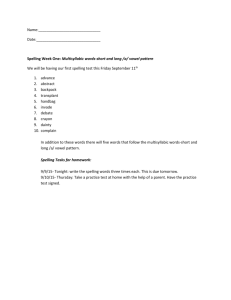

Vocabulary Instruction for Students who Read Braille Mackenzie Savaiano Donald Compton, Deborah Hatton, Blair Lloyd AER International July 31, 2014 Slide 2 - Overview Why is Vocabulary Important? My Study Research Questions Basic Design Examples of Results What Does This Mean for Instruction? Slide 3 - Figure of Reading Comprehension Model Description: The figure is a flow chart with five major boxes – braille tactile input, word identification, comprehension processes, prior knowledge, linguistic system. Except for tactile input, these boxes contain more information. Word Identification: there are three circles – orthographic units, phonological units, word representation. Orthographic units and phonological units are connected by a double-headed arrow and surrounded by a box. This box is connected to word representation by a double-headed arrow. Comprehension Processes: there are four boxes – surface code, textbase, situation model, and inferences. Surface code is connected to textbase by a double-headed arrow, and textbase is connected to situation model by a double-headed arrow. The inferences box is connected to surface code and textbase by double-headed arrows. Prior Knowledge: includes general background knowledge and vocabulary. Linguistic System: includes syntax, morphology, and phonolfy. Beginning at the bottom of the chart, a single-headed arrow leads from braille tactile input to word identification. Continuing up, a double-headed arrow connects word identification to comprehension processes. At the top, a double-headed arrow connects word identification to prior knowledge. Finally, another double-headed arrow connects comprehension processes to linguistic system. Reciprocal relationship between vocabulary, comprehension, and amount of reading (Nagy, 2005) Students who are blind have less exposure to text Affects amount of background knowledge Slide 4 - Vocabulary Instruction Direct instruction (Jitendra, Edwards, Sacks, & Jacobson, 2004; Marulis & Neuman, 2010; NICHD, 2000; Pany & Jenkins, 1978; Pany, Jenkins, & Schreck, 1982) Word spellings presented Facilitates word learning (Ehri & Rosenthal, 2007; Rosenthal & Ehri, 2008) Braille does not affect spelling ability (Clark & Stoner, 2008; Clark-Bischke & Stoner, 2009; Wall-Emerson, Holbrook, & D’Andrea, 2009) Slide 5 - In Print Spelling Not Present (description: drawing of a big truck) Spelling Present (description: drawing of a big truck with the word “rig” underneath) Slide 6 - In Braille? Spelling Not Present (description: empty box) Spelling Present (description: photograph of braille flashcard with top right corner cut and the word ashamed written in braille using contractions) Slide 7 - Research Question Do students who are blind learn: 1) the meanings of words more efficiently and 2) to spell words more accurately via flashcard vocabulary instruction relative to auditory only vocabulary instruction? Slide 8 - Design Adapted alternating treatments design (AATD; Sindelar, Rosenberg, & Wilson, 1985; Wolery, Gast, & Hammond, 2010) Nonreversible behaviors Compare efficiency of instructional strategies Description: Table showing differences between the two instructional strategies Flashcard and Auditory Only. There are three columns for each instructional strategy – word, definition, sentence. There are two rows - speech, braille. The letter “x” in a box indicates that the instructional strategy includes this item. Flashcard includes: word, definition, sentence in speech and word in braille. Auditory Only includes: word, definition, and sentence in speech. Slide 9 - Pretests EVALS Braille Reading Assessment (Texas School for the Blind and Visually Impaired, 2007) Woodcock-Johnson III Normative Update Braille Adaptation (WJ-III BA; Jaffe & Henderson, 2010) Word ID Word Attack Passage Comprehension Developmental Spelling Inventory (Ganske, 2000) Slide 10 - Description of Participants Description: Table includes three columns of participants names: Peter, Helen, Vincent. Table includes seven rows: age (in years), classification, visual diagnosis, visual acuity, braille contractions, WJ-III Braille Adaption, Psychological Assessment (WISC-IV). The following information follows the order of rows. Peter: 12.7; MD (blind and LD); bilateral anophthalmia; NLP (O.U.); 131/189 (69%); Letter-word ID=2.5 GE, Passage Comp.=1.9 GE, Word Attack=2.5 GE; Verbal Comp.=68, Working Memory=80, Verbal Deviation=68. Helen: 11.1; Blind; optic nerve hypoplasia; NLP (O.S.), LP (O.D.); 168/189 (89%); Letter-word ID=4.9 GE, Passage Comp.=2.1 GE, Word Attack=14.8 GE; Verbal Comp.=81, Working Memory=68, Verbal Deviation=73. Vincent: 9.5; MD (blind, LD, OHI, Autism); retinopathy of prematurity; LP (O.U.); 169/189 (89%); Letter-word ID=3.2 GE, Passage Comp.=2.1 GE, Word Attack=2.8 GE; Verbal Comp.=93, Working Memory=88, Verbal Deviation=90. Abbreviations: MD = multiple disabilities; LD = learning disabilities; OHI = other health impaired; ASD = autism spectrum disorder; ID = intellectual disabilities; NLP = no light perception; O.U. = both eyes; O.S. = left eye; LP = light perception; O.D. = right eye; CF = counts fingers; WJ-III = Woodcock-Johnson III Tests of Achievement; WISC-IV = Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children IV; RIAS = Reynolds Intellectual Assessment Scales Slide 11 - Word Sets The Living World Vocabulary (Dale & O’Rourke, 1981) The English Lexicon Project (Balota et al., 2007) Medical Research Council (MRC) Psycholinguistic Database (Coltheart, 1981) Equivalence Length Number of syllables Part of speech Grade level Frequency OLD PLD Imageability/concreteness Number of contractions Slide 12 - Definitions Triangulated from 3 sources The Living World Vocabulary (Dale & O’Rourke, 1981) Merriam-Webster Word Central Merriam-Webster Learner’s Dictionary Criteria Five or fewer words Did not include the word or part of the word Slide 13 - Sentences Criteria Used the exact form of the word Provided additional context for the word Did not restate the definition Had ten or fewer words Slide 14 - Dependent Variables Definition Recall 2 = correct response 1 = generalized response 0 = incorrect Spelling 2 = correct spelling, contracted 1 = correct spelling, uncontracted or incorrect contraction 0 = incorrect Slide 15 - General Procedures Probe Ask for meaning Ask for spelling Instruction Target word Participant repeats Target word definition Target word in sentence Target word definition Participant repeats definition Slide 16 - General Procedures Probe Ask for meaning: What does [frantic] mean? Ask for spelling: How do you spell [frantic]? Instruction Target word Participant repeats Target word definition Target word in sentence Target word definition Participant repeats definition Slide 17 - General Procedures Probe Ask for meaning Ask for spelling Instruction Target word Participant repeats Target word definition Target word in sentence Target word definition Participant repeats definition Description: Some words within instruction are highlighted to emphasize the repetition built into the procedure. “Target word” is highlighted in bold four times; “definition” is highlighted in green two times; “participant repeats” is highlighted in red two times. Slide 18 - General Procedures Probe Ask for meaning Ask for spelling Instruction The next word is tweed. What is the word? Participant repeats Tweed means wool cloth. The man wore tweed pants. Tweed means wool cloth. What does tweed mean? Participant repeats definition Description: The words are highlighted as in the previous slide, except the general wording is replaced with words from a specific example. “Tweed” is highlighted in bold four times; “wool cloth” is highlighted in green two times; “participant repeats” is highlighted in red two times. Slide 19 - General Results Sessions to Mastery Description: Table of Number of sessions to mastery for each participant. There are four rows: Flashcard, Auditory, Best Alone (Auditory). Peter: 6, 4, 8. Helen: 23, 17, 16. Vincent: 9, 7, 6. Slide 20 - General Results Average time per session Description: Table of average time per session in minutes (range). There are three column: Initial Probe, Comparison, Best Alone. Peter: 10.5(9.0-12.3) n=5; 12.8(7.2-16.4) n=6; 10.8(8.9-11.9) n=8. Helen: 7.3(6.5-8.6) n=3; 10.5(6.3-13.2) n=23; 10.9(7.6-13.3) n=16. Vincent: 10.4 (9.4-12.2) n=3; 21.2(15.3-25.6) n=9; 25.4(22.5-27.7) n=6. Slide 21 - Peter: Graph of Definition Recall Slide 22 - Vincent: Graph of Definition Recall Slide 23 - Peter: Graph of Spelling Slide 24 - Helen: Graph of Spelling Slide 25 - What Does This Mean for Instruction? Surprising results - not consistent with previous findings with students who read print (i.e., Rosenthal & Ehri, 2008) Listening and reading braille may require more cognitive load than listening and reading print Less efficient for certain student profiles Slide 26 - Profile - Helen Description: Shows Helen’s column from Slide 10 with emphasis placed on WJ-III scores and working memory score from the WISC-IV. Slide 27 - Helen: Graph of Definition Recall Slide 28 - Profile - Vincent Description: Shows Vincent’s column from Slide 10 with emphasis placed on MD classification. Slide 29 - Vincent: Graph of Spelling Slide 30 - Can We Still Use Flashcards? YES! Differences between two conditions was not instructionally relevant (though it was scientifically relevant) Slight procedural change Importance of spelling outweighs benefits of learning meanings 3 days sooner Separate listening and reading tasks Slide 31 - Questions Contact: msavaiano2@unl.edu Slide 32 - References Balota, D. A., Yap, M. J., Cortese, M. J., Hutchison, K. A., Kessler, B., Loftis, B., Neely, J. H., Nelson, D. L., Simpson, G. B., & Treiman, R. (2007). The English lexicon project. Behavior Research Methods, 39, 445-459. Clark, C. & Stoner, J. B. (2008). An investigation of the spelling skills of braille readers. Journal of Visual Impairments & Blindness, 102(9), 553-563. Clark-Bischke, C., & Stoner, J. B. (2009). An investigation of spelling in the written compositions of students who read braille. Journal of Visual Impairment & Blindness, 103(10), 668-679. Coltheart, M. (1981). The MRC psycholinguistic database. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 33A, 497-505. Dale, E., & O'Rourke, J. (1981). The living word vocabulary. Chicago, IL: World Book. Ehri, L. C., & Rosenthal, J. (2007). Spellings of words: A neglected facilitator of vocabulary learning. Journal of Literacy Research, 39, 389-409. Ganske, K. (2000). Word journeys: Assessment-guided phonics, spelling, and vocabulary instruction. New York, NY: Guilford Press. Ganske, K. (1999). The developmental spelling analysis: A measure of orthographic knowledge. Educational Assessment, 6, 41-70. Slide 33 - References Jaffe, L. E., & Henderson, B. W. (with Evans, C. A., McClurg, L. & Etter, N.). (2010). Woodcock-Johnson III Tests of Achievement Normative Update – Braille Adaptation (2nd ed.). Louisville, KY: American Printing House for the Blind. Jitendra, A. K., Edwards, L. L., Sacks, G., & Jacobson, L. A. (2004). What research says about vocabulary instruction for students with learning disabilities. Exceptional Children, 70, 299-322. Marulis, L. M., & Neuman, S. B. (2010). The effects of vocabulary instruction on young children’s word learning: A meta-analysis. Review of Educational Research, 80, 300-335. Nagy, W. (2005). Why vocabulary instruction needs to be long-term and comprehensive. In E. H. Hiebert & M. L. Kamil (Eds.), Teaching and learning vocabulary: Bringing research to practice (pp.27-44). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD). (2000). Report of the National Reading Panel. Teaching children to read: An evidencebased assessment of the scientific research literature on reading and its implications for reading instruction: Reports of the subgroups (NIH Publication No. 00-4754). Washington, DC: U.S. Pany, D., & Jenkins, J. R. (1978). Learning word meanings: A comparison of instructional procedures. Learning Disability Quarterly, 1, 21-32. Slide 34 - References Pany, D., Jenkins, J. R., & Schreck, J. (1982). Vocabulary instruction: Effects on word knowledge and reading comprehension. Learning Disability Quarterly, 5, 202-215. Perfetti, C. A., Landi, N., & Oakhill, J. (2005). The acquisition of reading comprehension skill. In M. Snowling & C. Hulme (Eds.), The science of reading: A handbook (pp. 227-247). Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing. Rosenthal, J., & Ehri, L. C. (2008). The mnemonic vale of orthography for vocabulary learning. Journal of Educational Psychology, 100, 175-191. Sindelar, P. T., Rosenberg, M. S., & Wilson, R. J. (1985). An adapted alternating treatments design for instructional research. Education & Treatment of Children, 8, 67-76. Texas School for the Blind and Visually Impaired. (2007). EVALS: Evaluating visually impaired students using alternate learning standards emphasizing the expanded core curriculum [Assessment tool]. Austin, TX: Texas School for the Blind and Visually Impaired. Wall-Emerson, R. W., Holbrook, M. C., & D’Andrea, F. M. (2009). Acquisition of literacy skills by young children who are blind: Results from the ABC Braille Study. Journal of Visual Impairment & Blindness, 103(10), 610-624. Wolery, M., Gast, D. L., & Hammond, D. (2010). Comparative intervention designs. In D. Gast (Ed.), Single subject research methodology in behavioral sciences (pp. 329-381). New York, NY: Routledge.