Newsletter

advertisement

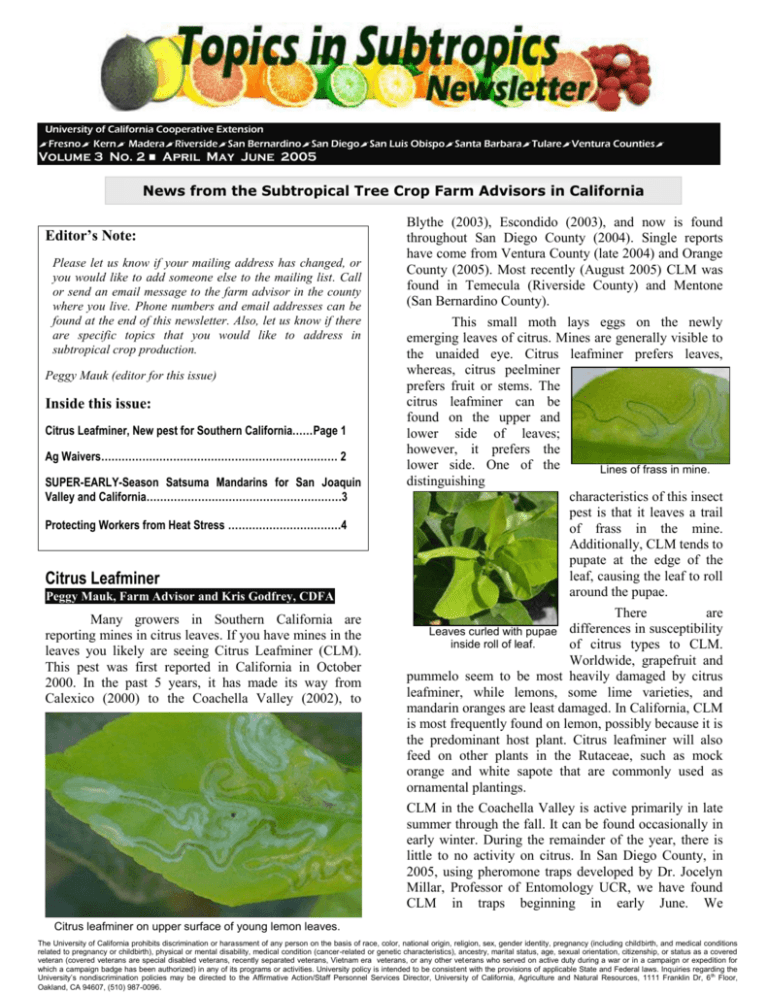

University of California Cooperative Extension Fresno Kern MaderaRiversideSan BernardinoSan DiegoSan Luis ObispoSanta BarbaraTulareVentura Counties Volume 3 No. 2 April May June 2005 News from the Subtropical Tree Crop Farm Advisors in California Editor’s Note: Please let us know if your mailing address has changed, or you would like to add someone else to the mailing list. Call or send an email message to the farm advisor in the county where you live. Phone numbers and email addresses can be found at the end of this newsletter. Also, let us know if there are specific topics that you would like to address in subtropical crop production. Peggy Mauk (editor for this issue) Inside this issue: Citrus Leafminer, New pest for Southern California……Page 1 Ag Waivers…………………………………………………………… 2 SUPER-EARLY-Season Satsuma Mandarins for San Joaquin Valley and California…………………………………………………3 Protecting Workers from Heat Stress ……………………………4 Citrus Leafminer Peggy Mauk, Farm Advisor and Kris Godfrey, CDFA Many growers in Southern California are reporting mines in citrus leaves. If you have mines in the leaves you likely are seeing Citrus Leafminer (CLM). This pest was first reported in California in October 2000. In the past 5 years, it has made its way from Calexico (2000) to the Coachella Valley (2002), to Blythe (2003), Escondido (2003), and now is found throughout San Diego County (2004). Single reports have come from Ventura County (late 2004) and Orange County (2005). Most recently (August 2005) CLM was found in Temecula (Riverside County) and Mentone (San Bernardino County). This small moth lays eggs on the newly emerging leaves of citrus. Mines are generally visible to the unaided eye. Citrus leafminer prefers leaves, whereas, citrus peelminer prefers fruit or stems. The citrus leafminer can be found on the upper and lower side of leaves; however, it prefers the lower side. One of the Lines of frass in mine. distinguishing characteristics of this insect pest is that it leaves a trail of frass in the mine. Additionally, CLM tends to pupate at the edge of the leaf, causing the leaf to roll around the pupae. There are differences in susceptibility of citrus types to CLM. Worldwide, grapefruit and pummelo seem to be most heavily damaged by citrus leafminer, while lemons, some lime varieties, and mandarin oranges are least damaged. In California, CLM is most frequently found on lemon, possibly because it is the predominant host plant. Citrus leafminer will also feed on other plants in the Rutaceae, such as mock orange and white sapote that are commonly used as ornamental plantings. Leaves curled with pupae inside roll of leaf. CLM in the Coachella Valley is active primarily in late summer through the fall. It can be found occasionally in early winter. During the remainder of the year, there is little to no activity on citrus. In San Diego County, in 2005, using pheromone traps developed by Dr. Jocelyn Millar, Professor of Entomology UCR, we have found CLM in traps beginning in early June. We Citrus leafminer on upper surface of young lemon leaves. The University of California prohibits discrimination or harassment of any person on the basis of race, color, national origin, religion, sex, gender identity, pregnancy (including childbirth, and medical conditions related to pregnancy or childbirth), physical or mental disability, medical condition (cancer-related or genetic characteristics), ancestry, marital status, age, sexual orientation, citizenship, or status as a covered veteran (covered veterans are special disabled veterans, recently separated veterans, Vietnam era veterans, or any other veterans who served on active duty during a war or in a campaign or expedition for which a campaign badge has been authorized) in any of its programs or activities. University policy is intended to be consistent with the provisions of applicable State and Federal laws. Inquiries regarding the University’s nondiscrimination policies may be directed to the Affirmative Action/Staff Personnel Services Director, University of California, Agriculture and Natural Resources, 1111 Franklin Dr, 6 th Floor, Oakland, CA 94607, (510) 987-0096. anticipate that CLM in San Diego County will disappear in late fall when temperatures drop. In two years of surveys, CLM has not been found to be active in San Diego County until early summer. We do not know if CLM is dormant when it is not active in citrus (winter through spring) or if it is moving to an alternate host. Control: biological and chemical For mature citrus, damage caused by CLM is mostly cosmetic. The damaged leaves can be a concern if leaves are being harvested for market. Yield reductions caused by CLM have not been documented in California. On mature trees, even though leaf damage will be apparent, chemical control should not be necessary. Worldwide, biological control has been sufficient in reducing CLM. This is true for the Coachella Valley. Dr. J.M. Heraty, Professor of Entomology UCR, reported 9 species of parasites (Closterocerus utahensis and Cirrospilus coachellae, predominating) found to be attacking CLM in the Coachella Valley. These parasites helped to reduce the damage from CLM on mature trees. The number of parasites and level of control in San Diego County is not known; however, minimizing chemical control will increase the potential of beneficial insects, including parasitic and predatory insects, to control CLM. Citrus leafminer is mainly a concern in young citrus trees (<4 years of age). Young trees tend to produce numerous leaf flushes and thus CLM can build more rapidly. Severely damaged leaves can drop and thus young trees could potentially be defoliated by CLM but this is not typical in California. So far, we have not observed consecutive defoliations which would be most damaging to young trees. Where control is necessary such as young trees, there are a number of pesticides registered for use in controlling CLM. For more information, please contact your local pest control advisor or your local farm advisors. There are restrictions for use of pesticide products so please read the label carefully before applying any pesticide. Citrus leafminer is a “B”-rated pest. This means that citrus packinghouses in areas not infested with CLM should accept fruit and bins from areas infested with CLM as long as they if they can be inspected (certified) at their origin and found apparently free from green citrus foliage OR the fruit and bins are covered (tarped) to reduce the risk of foliage being blown out during transport. Once tarped bins are in the packinghouse they must collect and destroy all green foliage associated with citrus fruit and harvest bins. Before shipping trees or fruit, please check with you local Ag Commissioner to determine if there are compliance agreements are in place for your county. Ag Waivers Ben Faber and Mary Bianchi, Farm Advisors in Ventura and San Luis Obispo Counties The Federal Clean Water Act (CWA) has resulted in significant improvements in surface water quality, achieved mainly through reducing discharge of substances from point sources like municipal sewage treatment plants and industrial facilities. These point source discharges must have permits, with permitted limits for the amounts of specific substances they are allowed to release. In order to maintain a permit, the holder must prove their compliance through constant water quality monitoring. The water quality standards on which these permits are based often vary, depending on the uses that have been identified for the water. California Water Law requires the State to identify how surface water is used in our state, monitor surface water quality to ensure the water can be used for those purposes, prioritizes water bodies for regulatory action if that use is found to be impaired, , and develop daily maximum discharges (or Total Maximum Daily Loads (TMDLs)) for each substance for each water quality impaired segment of stream, leak, etc. The levels of discharge substance must be reduced, either by changing the discharge permit for cities and industries or reducing contributions of the substance from other sources. Agricultural irrigation has many benefits, but also some unintended impacts on surface water quality. Pesticides, sediments, nutrients, salinity and altering receiving water body temperatures have been associated with agricultural runoff. It would be almost impossible to issue permits for farm discharges, given that runoff would have to be constantly monitored, something possible for an industrial discharge pipe (point source), but not for a whole farm (non-point source). Until recently, those impacts were largely accepted by the Regional Water Quality Control Boards (RWQCBs) as the natural state of affairs. The Regional Boards have the legal authority to set water quality standards and to regulate the discharge of pollutants into those waters. To provide agriculture with legal protection, most Regional Boards covered discharges from agricultural land with a blanket waiver, which provided exemption from active regulation. In most cases these waivers were issued years ago. Reduction of pollutants associated with agricultural runoff has been addressed mainly through Farm Bill programs like Conservation Compliance, the Conservation Reserve Program and Environmental Quality Incentives Program, and other voluntary programs that encouraged landowners to better control runoff. However, some point source permit holders have argued that these voluntary programs have been insufficient and non-point dischargers like agriculture need to do more. Recent changes to California Water Law require that, every five years, the RWQCBs must evaluate any waivers to permits they adopt. If the Board grants an industry a waiver to a permit, the waiver must be “conditional” and must prove to be in the public interest (i.e. it must be shown to protect water quality).. The Central Valley and the Central Coast Regional Boards have begun implementing programs to issue these waivers in. Soon a program will be started in the Los Angeles/Ventura region. These conditional waivers all require some monitoring and the identification of current or potential practices that could protect or improve water quality. In all three regions, growers will be allowed to apply for a waiver as a group or as individuals. The former case will probably be easier and less expensive for most growers. Fees to cover the cost of running the programs will come from both the State as well as local compliance efforts. What can individual growers do? Get informed and involved. Learn what Region you’re farming in and what the current status is of both your conditional waiver and any pending TMDL’s. You can access this information at http://waterboards.ca.gov. Learn more about the practices that are currently part of your regular grove management that already protect surface and ground water quality and take credit for what you are already doing! Learn more about practices that help protect surface and ground waters from the potential pollutants of concern in your watershed. Begin a planning program to schedule any needed improvements into your budgets. In your field, soil is one of, if not your greatest assets. If the same soil moves offsite to surface water, it becomes a pollutant. Remember that practices that prevent pollutants from moving away from their original site are generally much less expensive than practices to remove pollutants once they make it to surface or ground water. Choose those practices that keep sediments, nutrients, and pesticides on site where they make, not cost, you your profits. SUPER-EARLY-Season Satsuma Mandarins for San Joaquin Valley and California C. Thomas Chao, Associate Extension Specialist The fresh citrus market worldwide has changed dramatically in the past 20 years. Consumers and supermarkets now prefer easy-peeling, seedless, great tasting mandarins with nice rind color. As a result, mandarins are now the fastest growing sector of the fresh citrus industry in California and around the world. Satsuma mandarin (Citrus unshiu Marco.) is an easypeeling and completely seedless mandarin even in mixed plantings. It is commonly grown in Japan, China, and there is some acreage in California. The agricultural code of the State of California states that any citrus material entering California regardless of its point of origin, foreign or domestic, must enter through the Citrus Clonal Protection Program (CCPP) of Department of Plant Pathology, UC Riverside (www.ccpp.ucr.edu). The CCPP is responsible for testing citrus varieties for pathogens and eliminating pathogens for all citrus cultivars to be introduced into California. Since 1990, dozens of new Satsuma cultivars have gone through the CCPP for introduction into California but none of them have been evaluated for their commercial production potential. In May 2001, a top-work trial of 17 Satsuma cultivars was initiated with Carrizo citrange [C. sinensis (L.) Osbeck x Poncirus trifoliata (L.) Raf.] as rootstock and Valencia orange [C. sinensis (L.) Osbeck] as interstock near Santa Paula, Ventura County with cooperation from the Limoneira Company. The list of 17 Satsuma cultivars used in the trial is shown in Table 1. Trees set the first crop in the fall of 2003. In 2004, there was a significant fruit load (see picture). Fruit quality data were collected from September 1 to December 15, 2004 when collections were ended due to record rainfall and destruction of roadway. Among 17 cultivars, four of them are early season Satsumas, ‘Armstrong’, ‘Miyagawa’, ‘S9’, and ‘Xie-Shan’. The fruit quality data of these four Satsumas from September 1 to November 11, 2004 are shown in Table 2. ‘Miyagawa’ reached legal maturity (S/A=6.5) as early as September 9, 2004 with S/A ratio of 7.04. ‘Miyagawa’ had a sharp flavor because of the balance of a moderately high acid level with a moderate sugar level. It also had a very nice internal orange flesh color compared with the other three 2004 Fruit load for ‘Miyagawa’ Satsuma Table 1. List of 17 Satsuma cultivars in the trial and their background information. Name CCPP no. Background Armstrong VI 580 Early ‘Owari’ selection from Louisiana. It does not have high sugar, very plain. Aoshima VI 584 Leading late season Satsuma from Japan. Vigorous, densely foliated and precocious tree with large, oblate shaped fruit, high sugar and high acid level resulted in intense, well-balanced flavour. Aqudzera VI 642 Mid to late season Satsuma from Japan. Dart North VI 556 ‘Owari’ selection from SJV, CA, later than ‘Owari’. Dart South VI 557 ‘Owari’ selection from SJV, CA, later than ‘Owari’. Dungan VI 558 ‘Owari’ selection from SJV, CA, later than ‘Owari’. Iveriya VI 643 Mid-late season cultivar from Japan. KawanoWase VI 525 Mid season Satsuma from Japan selected back in 1800’s. KunoWase VI 555 Early season Satsuma from Japan. Miyagawa VI 612 Most extensively grown early season Satsuma in Japan. Trees lack vigour compared with other Wase cvs such as its daughter cv ‘Miho Wase’ and ‘Okitsu Wase’. According to Saunt (2000), ‘Miyagawa’ matures slightly earlier than ‘Miho’ but a week or more later than ‘Okitsu’. Flavour is quite sharp because the moderately high acid label coupled with sugar level that are not particular high. S2 VI 635 Unknown cultivar from China. S6 VI 640 Unknown cultivar from China, may have higher cold tolerance. S7 VI 641 Unknown cultivar from China, may have higher cold tolerance. S9 VI 636 Unknown cultivar from China. SilverHill VI 603 Nucellar seedling selection of ‘Owari’ from a cross made by W.T. Swingle of USDA in Florida around 1908. It is later than ‘Owari’. Shirokolistvennyi VI 602 Unknown cv from former Soviet Union with high cold tolerance. Xie-Shan VI 621 ‘Xie-Shan’ is the Chinese translation of this cv from Japan. The original name is ‘Wakiyama’ cultivars. ‘Xie-Shan’ had a higher acid level than the other three cultivars. It had a very unique flavor and taste that was different from other Satsumas. ‘Armstrong’ had lower sugar level than the other three cultivars and tasted less sweet than the others. Five early season Satuma (1=’Xieshan’, 2=’Miyagawa’, 3=’S9’, 4=’Kuno Wase’ and 5=’Armstrong’) before and after degreening treatment with 0.5mg/L ethylene for 72 hours with fruit harvested on October 6, 2004, Santa Paula, CA. A small scale degreening experiment was carried out in October 2004 with cooperation from J. Doctor of Sunkist Growers. Ten fruit each of five early Satsuma cultivars, ‘Armstrong’, ‘KunoWase’, ‘Miyagawa’, ‘S9’, and ‘Xie-Shan’ were harvested on October 6, 2004 and treated with 0.5 mg/L ethylene for 72 hours. Rind color of all five Satsuma cultivars was enhanced with the ethylene treatment. UC Lindcove Research and Education Center (LREC) near Exeter, CA began fruit quality data collection for ‘Miyagawa’ and ‘Xie-Shan’ the first time in fall 2004. In the first half of October 2004 (October 1 – 15), ‘Miyagawa’ and ‘Xie-Shan’ had S/A ratios of 16.8 and 16.2, respectively. ‘Frost Owari’, ‘Okitsu Wase’ and ‘Dobashi Beni’ had S/A ratios of 7.4, 9.9, and 7.6, respectively at the same time. ‘Miyagawa’ and ‘XieShan’ had much higher S/A ratios than the three commonly grown Satsumas in California. We do not have fruit quality data for ‘Miyagawa’ and ‘Xie-Shan’ in late August and September from San Joaquin Valley; however, based on the information we have collected we feel that ‘Miyagawa’ and ‘Xie-Shan’ may be ready for harvest in the San Joaquin Valley of CA as early as in mid September, which is about one month earlier than our current early Satsuma, ‘Okitsu Wase’ and Dobashi Beni’. If our projections hold true for harvest of ‘Miyagawa’ and ‘Xie-Shan’ in mid-September, these two cultivars will be the only easy-peeling and completely seedless SUPER-EARLY mandarins in the market. The mandarins from the Southern Hemisphere finish in late August and the early seedy ‘Fallglo’ from Florida is not in the market yet. We do not have fruit quality data for ‘S9’ Satsuma in the San Joaquin Valley Table 2. Fruit quality data of four early season Satsuma from Santa Paula, CA in 2004 Armstrong Miyagawa S9 Date Ad.Brix % Acid S/A Ad.Brix % Acid S/A Ad.Brix % Acid S/A Ad.Brix 9/1/04 9/9/04 9/15/04 9/22/04 9/22/04 10/6/04 10/12/04 10/19/04 11/2/04 11/10/04 6.00 6.29 6.53 7.52 9.58 10.1 9.68 10.59 11.23 12.84 8.8 8.8 8.4 8.3 9.1 9.1 9.3 9.2 8.7 10.0 8.3 7.8 7.8 8.2 8.1 8.5 9.8 8.5 8.1 8.4 2.0 1.5 1.4 1.3 1.1 1.1 1.0 1.1 0.9 0.7 4.06 5.46 5.56 6.37 7.62 7.85 9.53 7.62 9.45 11.59 8.8 8.7 8.7 9.0 9.7 8.7 10.5 10.0 9.8 9.9 1.6 1.2 1.2 1.1 1.1 1.0 1.0 0.9 0.8 0.8 yet. Based on the data from Santa Paula, ‘S9’ has lower S/A ratio than ‘Miyagawa’ but higher S/A ratio than ‘Xie-Shan’. Therefore ‘S9’ fruit should also mature early in San Joaquin Valley as ‘Miyagawa’ and ‘Xie-Shan’. ‘S9’ at LREC also has been observed to have very smooth rind that makes it a plus character when compared among other Satsumas. ‘Miyagawa’ Satsuma was released publicly in June 2005 by CCPP. CCPP is scheduled to release ‘S9’ and ‘Xie-Shan’ in September 2005. Therefore, these three cultivars could potentially be available for planting in 2006 or 2007. A new trial consisting of five early Satsuma cultivars (‘MihoWase’, ‘Miyagawa’, ‘S9’, 5.53 7.04 7.48 8.2 8.88 8.62 10.66 11.19 12.29 12.93 8.5 8.5 8.4 8.6 8.8 8.8 9.0 8.6 8.9 9.2 1.4 1.4 1.3 1.6 0.9 0.9 0.9 0.8 0.8 0.7 Xie-Shan % Acid 1.9 4.6 1.3 1.2 1.1 1.1 0.9 0.9 0.8 0.8 S/A 4.65 5.43 6.24 7.13 8.51 8.46 10.24 9.93 11.38 12.84 ‘Xie-Shan’, and ‘Armstrong’) on 3 rootstocks (C35, Carrizo, and Trifoliate) will be planted in spring 2006 at six locations through out all citrus growing areas of CA. We will also continue to take fruit quality and yield data at our Santa Paula site. We need to learn more about the commercial production potential of these cultivars in the near future so that growers can make the best decisions based on data generated from their production area. BE SAFE! Driving while talking on your mobile phone may be your last call! Farm Advisors Gary Bender – Subtropical Horticulture, San Diego Phone: (858) 694-2856 Email to: gsbender@ucdavis.edu Website: http://cesandiego.ucdavis.edu Mary Bianchi – Horticulture/Water Management, San Luis Obispo Phone: (805) 781-5949 Email to: mlbianchi@ucdavis.edu Website: http://cesanluisobispo.ucdavis.edu Ben Faber – Subtropical Horticulture, Ventura/Santa Barbara Phone: (805) 645-1462 Email to: bafaber@ucdavis.edu Website: http://ceventura.ucdavis.edu Peggy Mauk – Subtropical Horticulture, Riverside Phone: (951) 683-6491 Ext. 221 Email to: pamauk@ucdavis.edu Website: http://ceriverside.ucdavis.edu Neil O’Connell – Citrus/Avocado, Tulare Phone: (559) 685-3309 ext 212 Email to: nvoconnell@ucdavis.edu Website: http://cetulare.ucdavis.edu Craig Kallsen - Subtropical Horticulture and Pistachios, Kern Phone: (661) 868-6221 Email to: cekallsen@ucdavis.edu Website: http://cekern.ucdavis.edu Eta Takele – Area Ag Economics Advisor Phone: (951) 683-6491 ext. 243 Email to: ettakele@ucdavis.edu Website: http://ceriverside.ucdavis.edu Mark Freeman – Citrus and Nut Crops, Fresno/Madera Phone: (559) 456-7265 Email to: mwfreeman@ucdavis.edu Website: http://cefresno.ucdavis.edu/newsletter.htm Topics in Subtropics April, May, June, 2005 Neil O’Connell Farm Advisor