Zellmer&Bhappu04 - Southern Methodist University

advertisement

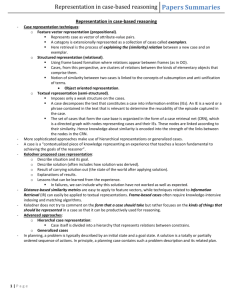

BEYOND DEMOGRAPHIC HETEROGENEITY: AN EXPLORATION OF PERCEIVED SIMILARITY IN TEAMS Mary E. Zellmer-Bruhn University of Minnesota Carlson School of Management 321 19th Avenue South Minneapolis, MN 55455 612-625-2342 612-626-1316 (fax) mzellmer-bruhn@csom.umn.edu Mary M. Maloney University of Minnesota Carlson School of Management 321 19th Avenue South Minneapolis, MN 55455 612-625-9009 612-626-1316 (fax) mmaloney@csom.umn.edu Anita D. Bhappu Southern Methodist University Cox School of Business P.O. Box 750333 Dallas, TX 75275-0333 214-768-2204 214-768-4099 (fax) abhappu@mail.cox.smu.edu Rommel O. Salvador Tulane University A.B. Freeman School of Business 7 McAlister Drive New Orleans, LA 70118 504-865-5532 504-865-6751 (fax) The authors thank Philip Bromiley, Mel Fugate, Theresa Glomb, Laurie Milton, Gerardo Okhuysen, and Pri Shah for helpful comments on earlier drafts of this manuscript. 1 BEYOND DEMOGRAPHIC HETEROGENEITY: AN EXPLORATION OF PERCEIVED SIMILARITY IN TEAMS ABSTRACT Recent research suggests that how teams perceive their differences influences team identity and social integration (Harrison, Price, Gavin, & Florey, 2002; Polzer, Milton, & Swann, 2002). We explore the formation and changes in team perceived similarity in a longitudinal sample of 25 teams. Results suggest that initially, perceived similarity about both surface and deep differences is driven by social category diversity. Over time, deep informational and value diversity produce conflict, which subsequently reduces perceptions of similarity. Finally, although initial levels of perceived similarity change, they have a powerful effect and persist, continuing to influence subsequent perceptions of similarity. 2 Today’s organizations increasingly rely on teamwork involving diverse members. Yet mixed empirical findings on diversity and team effectiveness have left unanswered theoretical and practical questions about how best to manage diverse teams. In an effort to address these questions, scholars called for more research incorporating intervening variables and multiple types of diversity (Milliken & Martins, 1996; Williams & O’Reilly, 1998; Pelled, Eisenhardt, & Xin, 1999). Recent research suggests that one such intervening variable, how groups perceive their differences, may be as important as the differences themselves to understanding the effects of team diversity (Earley & Mosakowski, 2000; Harrison, Price, Gavin, & Florey, 2002; Polzer, Milton, & Swann, 2002). The argument is that “perceptions of diversity reflect the psychological importance of, and carry the substantive impact of, actual diversity to team outcomes” (Ashforth & Mael, 1989; cf. Harrison et al., 2002: 1033). Understanding how group perceptions of team diversity form and evolve over time has the potential to provide insight into the complex relationship between team diversity and performance. Although the effects of diversity vary longitudinally (Watson et al., 1993), as is the case in many areas of management research (Mitchell & James, 2001) studies of the temporal aspects of diversity remain underrepresented in the literature. Our study contributes to the emerging body of research on perceptions of diversity by elaborating how perceived similarity - the degree to which members view themselves as having few differences - develops over the life of a team. We further develop this literature by proposing that conflict plays a role in the updating of perceived similarity. By contributing additional knowledge about perceived similarity in diverse teams, particularly how perceived similarity forms and changes during a team’s time together, this research moves beyond the static view of diversity in teams. In fact, we conceptualize perceived similarity to be an “emergent state” (Marks, Mathieu, & Zaccaro, 2001). As an emergent state, perceived similarity describes a cognitive state that is dynamic in 3 nature, influenced by the dispersion of static individual characteristics, and varying as a function of team experiences. Therefore, we expect perceived similarity to change during the life of a team. We examine the influence of multiple types of diversity on perceived similarity over time. Specifically, recent research makes the distinction between surface and deep diversity (Harrison, Price, & Bell, 1998). Surface diversity involves overt characteristics reflected in visible, physical features such as sex and race (Harrison et al., 1998:97), and deep diversity involves differences such as values, that are communicated through behavior and learned through interaction (p. 98). The key distinction is that surface diversity can be quickly assessed from visible cues, but deep diversity requires interaction and time to be revealed There are multiple categories of diversity that could be assessed as surface or deep. For surface diversity, we examine social category diversity, which is explicit, visible differences in social category membership such as race, sex, and ethnicity (Pelled, 1996; Jehn, Northcraft & Neale, 1999). For deep diversity, we examine informational and values diversity. Informational diversity involves differences in knowledge and perspectives that arise from work background, experience, education, and training, and values diversity involves differences in team members’ goals, and emphasis placed on various outcomes (Jehn et al., 1999). We expect that surface diversity (social category) and deep diversity (informational, value) exert different influences on perceived similarity over time because of the relative ease of assessment of surface diversity and the need for interaction to assess deep diversity. Furthermore, we argue that conflict influences perceived similarity (Jehn, 1997), with conflict acting as the group process mechanism that reveals informational and value diversity. Figure 1 depicts our hypothesized relationships, which we now describe in detail. -------------------------------------Insert Figure 1 about here -------------------------------------- 4 PERCEIVED SIMILARITY IN DIVERSE TEAMS Perceived similarity captures “a process assumed to occur but rarely assessed in diversity research (Riordan, 2000): the transmission of effects of actual team member diversity through perceptions of such differences” (Harrison et al., 2002: 1029). Team members base their perceived similarity of one another on individual traits or characteristics that are psychologically salient in their groups such as sex, race, or status (Lau & Murnighan, 1998). A number of studies and theoretical perspectives note the importance of perceived similarity. For example, perceived similarity enhances interpersonal attraction among individuals (Byrne, 1971; Secord & Backman, 1964), and perceived similarity in personal characteristics leads to stronger group attachments (Earley & Mosakowski, 2000; Harrison et al., 2002; Polzer et al., 2002). As such, perceived similarity intervenes between team diversity and team actions. For instance, Earley and Mosakowski (2000) theorized that team diversity influences the formation of hybrid team cultures through member’s perceptions of the presence of distinguishable subgroups. If members perceive very high diversity, they are more likely to develop a hybrid culture than if they perceive moderate levels of diversity. Earley and Mosakowski concluded that hybrid cultures are a key to performance success in highly diverse, multicultural teams, demonstrating the important role of perceptions of diversity in the diversity/performance chain. It should be noted that while this research identified the key role of perceptions, and perceived similarity was part of Earley and Mosakowski’s conceptual argument, perceived similarity was not directly measured in their study. Two subsequent studies provide empirical evidence that team members’ perceptions about their team diversity influence team outcomes such as social integration, and thereby strengthen evidence for the value in examining perceived similarity in efforts to refine theory about diversity’s influence in teams. Harrison et al. (2002) found that the actual diversity of student groups positively influenced perceived team diversity, which in turn decreased team social integration. Polzer et al. 5 (2002), included perceived similarity as a control variable when modeling interpersonal congruence and diversity in MBA teams, and also found that perceived similarity positively influenced team social integration and group identification. Both studies provide evidence that perceived similarity is an important intervening variable between team diversity and team outcomes. However, these studies examine perceived similarity at a single point in time, and do not address the possibility of temporal changes. Perceived Similarity is Dynamic We know from the literature that the influence of team diversity on team performance varies over time (Watson et al., 1993), that the influence of team diversity on team processes such as conflict is bounded by team longevity (Pelled, 1996), and that different types of diversity are not revealed simultaneously (Harrison et al., 2002). Harrison et al. (1998) argue that as members interact over time, they will uncover more deep diversity that may or may not align with their more obvious surface social category diversity. Team members may initially perceive themselves to be quite similar based on observable social category characteristics but find out that they are indeed very different after interacting, or vice versa. Hence, perceived similarity, as a cognitive appraisal of team diversity, can be regarded as an emergent psychosocial state that is fluid and mutable: a condition that changes as a function of time (Marks et al., 2001). Therefore, we expect that: H1: Perceived similarity changes during the time teams are together. Perceived Similarity at Team Formation When a team first forms, particularly if the team is composed of unfamiliar individuals, members operate with very little information from which to draw conclusions about each other. Even so, individuals quickly form impressions of others using whatever information is available (Ambady & Rosenthal, 1992) to ease discomfort stemming from uncertain expectations and to predict likely behaviors of their teammates (Allport, 1954). Under such conditions, where 6 individuals are uncertain about each other or the situation, they typically engage in selfcategorization (Grieve & Hogg, 1999; Mullin & Hogg, 1998) and social-categorization (Tajfel, 1978) by cognitively placing themselves and others into salient social groups. Salient social groups are often demarcated by observable and accessible demographic characteristics such as race, sex, and age (Allport, 1954; Jehn et al., 1999) in newly formed teams because there is a lack of information about other individual differences, such as information or values diversity. Therefore, teams use social category diversity to form initial perceptions about their similarity. By categorizing others and themselves, team members immediately have a basis for building relationships, and for forming behavioral expectations of each other because social category diversity is likely to influence their perceptions via social identity effects (Tajfel & Turner, 1986; Turner, Hogg, Oakes, Reicher, & Wetherell, 1987). Members with similar social categories assume they share information and values (Elsass & Graves, 1998), and probably have common past experiences (e.g. Pfeffer, 1983), which provides a basis for relational development. In fact, when members of newly formed teams are similar on social categories, they not only identify as belonging to the same in-group, but they actually minimize any observed differences among themselves (Brewer, Manzi, & Shaw, 1993), thereby reinforcing their perception of similarity (Brewer, 1987). However, if members of newly formed teams are different on social categories, they are likely to perceive themselves as being dissimilar, both in these visible categories and in other underlying dimensions (Chattopadhyay, 1999). Therefore, we expect that: H2: At team formation, surface (social category) diversity negatively influences perceived similarity about both surface and deep differences. The Role of Conflict It takes time for teams to develop a complete understanding of their team diversity because unlike surface differences, deep differences cannot be easily detected before team interaction. Even though teams base their initial perceptions of both surface and deep similarity on social category 7 differences, teams may actually discover that they have more or less in common than they initially assumed once they begin to interact. Therefore, any changes in perceived similarity are influenced both by initial perceptions of team diversity based on surface social category diversity, which affect early feelings of group identification (Polzer et al., 2002), and by deep differences such as informational and values diversity that become apparent as team members interact. How do teams recognize deep differences? We know that “diversity has its impact through the crucible of conflict” (Griffith & Neale, 2001: 399) and that conflict influences team outcomes (Alagna, Reddy, & Collins, 1982; Jehn et al., 1999; Jehn, Chadwick, & Thatcher, 1997; O’Reilly, Williams & Barsade, 1998; Pelled, 1996; Griffith & Neale, 2001; Jehn, 1995; Jehn et al., 1999; Williams & O’Reilly, 1998). Also, past research demonstrated that deep differences, on such characteristics as education, work experience, functional background, values, and personality (Jehn et al., 1999; Harrison et al., 1998), increase conflict. Specifically, informational diversity increases task conflict (Jehn et al., 1999) while value diversity increases task and relationship conflict (Jehn et al., 1999). Task conflict may spill over into relationship conflict because “it is difficult for individuals to present and receive criticism, and often the critic is blamed for the adverse reaction” (Jehn, 1997: 532). Therefore, we assert that latent, deep differences produce task and relationship conflict during team interactions. Thus, we expect that: H3: Once a team begins to interact, deep (informational, value) diversity increases conflict. The eruption of conflict in a team may cause members to see their team as diverse and result in them updating their perceptions of similarity. Updating perceptions occurs through two channels. First, conflict involves expressing contradictory opinions, and teams typically reject members for expressing deviant opinions which in turn reduces feelings of attraction within the team (Byrne, 1971). Jehn (1995) found that conflict within teams reduced interpersonal liking among members. Research on the relationship between similarity and attraction (Byrne, 1971) suggests that reduced 8 interpersonal liking stemming from conflict should decrease perceptions of similarity. Second, although previous research has emphasized conflict as an outcome of team diversity, we believe conflict also acts as a carrier of information about team diversity, which precipitates changes in perceived similarity. Without conflict, teams may not be aware of deep diversity in knowledge, approaches to work, and values. By revealing deep diversity, conflict illuminates important underlying variation among team members, which lowers their perceived similarity. The mechanisms of reducing interpersonal attraction and carrying information about differences should particularly affect perceptions of deep differences because initial perceptions on these dimensions were formed on tenuous information about social category diversity. Perceptions of surface differences are based on social category diversity that is present at formation, and doesn’t change over time. Therefore, perceptions of deep differences should be subject to updating based on emergent conflict. Therefore, we expect that: H4: Once a team begins to interact, conflict reduces perceived similarity about deep differences. The Persistence of Initial Perceived Similarity Information about deep diversity, which emerges as conflict during team interaction may not, however, result in sufficient updating of perceptions of similarity. In other words, although perceptions of similarity change over time, they may not change enough, and initial levels of perceived similarity may influence the change. Person perception theory (Allport, 1954) and attribution theory (Shaver, 1975) demonstrate that initial perceptions are tenacious. Early information helps to organize subsequent information (Asch, 1946). Initial information receives much more weight in the formation of perceptions than later information, even if later information is disconfirming of earlier information. Perceivers fail to sufficiently adjust their initial perceptions accordingly (Kahneman & Tversky, 1979). Thus, initial perceptions of similarity based on social category diversity at team formation may act as an anchor (Kahneman & Tversky, 1979) for 9 subsequent perceptions of similarity regardless of any new information about team diversity, or the lack thereof, which emerges during team interaction. Therefore, although perceived similarity changes during a team’s life, we expect that: H5: Initial perceived similarity influences final perceived similarity. METHODS Sample and Procedure Our sample consisted of first-semester, full-time Master’s of Business Administration (MBA) student teams at a large Mid-Western university. Before the semester, the MBA admissions office used sex, race, country of origin, previous education, and job experience to create four to six member teams. Once assigned, members of each team completed team project assignments for all required core courses during their first semester, and competed in an end-of-semester business simulation. Because these team projects accounted for a significant portion of students’ grades and learning opportunities, students took their membership and performance in the first-semester core teams very seriously. We collected data from first-semester core teams for two years’ incoming classes. We collected demographic data from admission records and surveyed team members to obtain information about perceived similarity, conflict, values diversity, and frequency of meetings. Students came from 38 different countries with 31% coming from countries other than the United States. Of the 241 individuals in our initial sample, 67% percent were Caucasian, 22% were Asian, 5% percent were Hispanic, 3% were Black and South Asian, respectively, and 23% were female. We surveyed teams at three different times during their first semester: at team formation before the start of the semester (T1), half way through the semester (T2), and during the final week of classes (T3). To strengthen the quality of our results, we only included in our analyses teams that had a withinteam response rate of 50% or more in all three time periods. This strict criterion resulted in final 10 sample of 25 teams, or a 54% team response rate. We conducted analyses to ensure that the teams retained in our final sample were not statistically different from those excluded due to low within team response rates. Among the set of individuals included in the final sample, fewer countries were represented than full sample (18 versus 38), but team diversity scores for nationality did not differ. ANOVA for all other variables in our model also revealed no statistically significant differences between the teams included in our final sample and those excluded. Given our research questions, data from these particular MBA teams have many desirable properties. The teams worked together in multiple classes and completed several projects together over a 15-16 week period. Teams performed meaningful work with significant consequences and had to manage different, potentially competing individual and team task priorities, making them similar to many teams in workplace settings. In addition to complex task demands with real consequences, the teams in our sample have another desirable characteristic. The team formation timing and launch process allows us to assess team perceptions at formation, before any significant interaction had occurred, enabling us to isolate the effects of surface versus deep diversity on perceived similarity over time. In organizational settings it would be difficult to find a set of teams with a common “zero” point. Previous studies of perceived similarity included teams where individuals may have known each other for longer and/or may have had previous interactions. For instance, Harrison et al. (2002) measured perceptions of teams of students enrolled in upper division undergraduate and graduate courses (and who were not new students) between the fifth and seventh week of the semester. Members of these teams had opportunity to interact and learn about each other before completing surveys about their perceptions. More similar to our design, Polzer et al. (2002) used MBA student teams put together by administrators, and used a measure of perceived similarity taken after 10 minutes of interaction. It is possible that the findings of these studies were affected by the choice of timing of data collection (Mitchell & James, 2001). Our sample and design 11 allow us to incorporate both aspects of these previous empirical studies: measurement of perceived similarity immediately upon team formation, and after several weeks of interaction. Measures In addition to the basic description of each measure, we provide information on withinteam agreement. Since several of our variables were created by aggregating data reported by individuals about their team (Klein & Koslowski, 2000), we calculated two indices of within-group agreement: the Lindell, Brandt, and Whitney (1999) revised version of the James, Demaree, and Wolf (1984) index, r*WG, or the r*WG(J) for J-item scales, and an Average Deviation Index, AD(J), for J-item scales (Burke & Dunlap, 2002 ). The r*WG index ranges from 0 (no agreement) to 1 (complete agreement) (James, Demaree, & Wolf, 1984). An acceptable cut-off criterion to demonstrate agreement is 0.60 (Glick, 1985). The AD(J) index is a measure of inter-rater agreement that computes the absolute average distances of group scores from that group’s median. Lower AD scores indicate smaller differences among team responses, with 0 indicating perfect agreement. Because the AD index does not have a fixed number as an upper bound, an appropriate test of statistical significance demonstrates within-group agreement (Dunlap, Burke & Smith Crowe, 2003). Perceived Similarity. We measured perceived similarity at T1 and T3 using an 8-item scale we developed to indicate the extent to which team members felt their team is similar with respect to cultural background, nationality, ethnicity, work habits, interaction styles, communication style, work ethic, and personalities. Items were rated on a Likert-type response scale (1 = disagree strongly, 7 = agree strongly). The first factor, consisting of three items (ethnicity, nationality, cultural background), represents perceived similarity about surface differences (alpha T1 = .92; T3 = .93). The second factor, consisting of five items (work habits, interaction styles, communication styles, work ethic, personalities), represents perceived similarity about deep differences (alpha T1 = .84; T3 = .88). A confirmatory factory analysis supported the two factor solution (at T1 CFI = 0.94, NNFI = 0.90, 12 and at T3 CFI =.93, NNFI = .88) (Bentler, 1990). For both perceived similarity about surface differences, and perceived similarity about deep differences, we aggregated individual ratings of perceived similarity by first calculating the mean for each set of items for each team member. We then computed the average of these means, obtaining a score for each form of perceived similarity at the team level. The median r*WG(10) was 0.62 at T1 and 0.60 at T3. Moreover, teams attained statistically significant AD indices on the eight items, on average.1 Both suggest adequate withinteam agreement. Social Category Diversity. Social category diversity concerns differences in social categories like ethnicity and sex (Pelled, 1996). We measured social category diversity using individual demographic information for each team member from MBA admissions records on sex, nationality, and race. The final sample included students from 18 different countries; we coded each country separately. We coded racial/ethnic background in five categories: Asian, Black, Caucasian, Hispanic or South Asian. Because each type of social category diversity we used in this study is a categorical variable, we used Teachman’s index (1980) to create a heterogeneity score for each. The higher the score, the more numerous and distributed the categories of heterogeneity are on a team. In the final sample, sex heterogeneity had a mean of .43 (s.d. = .27), national heterogeneity had a mean of .75 (s.d. = .27), and ethnic heterogeneity had a mean of .70 (s.d. =.32). Following Jehn et al. (1999), we combined the three types, using an average, to create an index of social category diversity. Informational Diversity. Informational diversity involves different knowledge and background perspectives in the team commonly arising from education and experience differences (Jehn et al., 1999: 743). We measured informational diversity using years of work experience and undergraduate major. 1 Years of work experience is the number of years worked before entering the Median AD(8) was 0.77 at T1 and 0.76 at T3. 13 MBA program, for which we calculated a coefficient of variation with mean = .53 (s.d. = .21). We used nine categories of undergraduate majors to create a Teachman score for the second component of informational diversity (mean = 1.35; s.d. = .18). Again, following Jehn et al. (1999), we combined years of work experience diversity and undergraduate major diversity to create an index of informational diversity. Values Diversity. To measure values diversity, we used eight items from the Personal Values Questionnaire (McBer & Company) to capture diversity in individual members values for achievement and for power. Achievement values involve the degree to which we value outperforming others and have high standards of excellence. Power values involve the degree to which we value being strong, influential, and controlling. Values diversity was measured at team formation. Individuals rated how important a set of items was to them. Sample items for achievement values are, Opportunities to take on more difficult and challenging goals and responsibilities, and Continual opportunities for personal growth and development. Sample items for power values are, Doing things that have a strong effect on others, and Taking forceful action. The rating scale ranged from 1 = “not important to me” to 5 = “extremely important to me.” The scale had an alpha of .76. For both need for power and need for achievement, we computed a coefficient of variation for each team as an indication of diversity. We combined the two scores to create an index of values diversity. Conflict. We measured intra-group conflict using six items reflecting task conflict and relationship conflict, based on the scales developed by Jehn (1995). For example, an item for task conflict read, Conflicts regarding ideas are very frequent in our team, and an item for emotional conflict read, Personality conflicts are evident in this team. The rating scale ranged from 1 = “disagree strongly” to 5 = “agree strongly”. We created a single composite score for conflict, computed as the average of all six items, based on a confirmatory factory analysis (CFI = 0.93, NNFI = 0.89, RMR = 0.06) that suggest the existence of a one-factor structure for conflict. Using a single composite score for task 14 and relationship conflict is consistent with research indicating that individuals are not able to distinguish among the different types of conflict (Griffith & Neale, 2001; Williams & O’Reilly, 1998; Pelled, 1996). Moreover, the subscale for task conflict also highly correlated with the subscale for relationship conflict (r = 0.63, p < 0.001). Internal consistency for the 6-item scale was 0.82 (alpha). Intra-group agreement was satisfactory, with a median r*WG(6) of 0.67 and 83% of the teams attaining statistically significant AD indices on all 6 items2, so we calculated the mean of the individual conflict ratings for the team to obtain a group-level measure for conflict. Controls. There may be subtle differences in the core MBA curriculum across two years of our data collection. For example, there were minor differences across the years in faculty and structure of orientation for the first semester. These differences may produce variations in team processes so we included a dummy variable for year in our models. There is pressure toward uniformity of attitudes in groups such that over time, as members interact more frequently, they perceive they are more similar -- or may actually become more alike – because they need to reduce cognitive dissonance (Festinger, 1954), so we included meeting frequency. Individual team members indicated the number of times their team met face-to-face since the beginning of the semester (1 = “1 to 4 times”, 2 = “5 to 9 times”, 3 = “10 to14 times”, 4 = “15 to 19 times” and 5 = “20 or more times”). These ranges were coded as ‘1’ for the lowest range and ‘5’ for the highest with mean = 3.7 (s.d. = .81). Median rWG was 0.60 at T2 and 0.88 at T3. Finally, we also controlled for team size since our sample contains teams of four to six members. RESULTS Descriptive statistics and correlations are presented in Table 1. -------------------------------------Insert Table 1 about here -------------------------------------2 Median AD(6) = 0.50. 15 Hypothesis 1 (H1) proposed that perceived similarity changes during the time teams are together. We tested H1 with paired t-tests. For perceived similarity about surface differences, the mean at T1 was 2.80 (s.d. = .36) and the mean at T3 was 2.62 (s.d. = .30). The decrease of 0.18 was marginally significant (t = 1.45, p < .10). For perceived similarity about deep differences, the mean at T1 was 3.88 (s.d. = .15) and at T3 was 3.25 (s.d. = .18). The decrease of 0.63 was statistically significant (t = 4.99, p < .001). Thus, both perceived similarity about surface differences and perceived similarity about deep differences changed over time. Specifically, in this sample, although both types of perceived similarity decreased, the change in perceived similarity about deep differences was larger. For the remainder of our hypotheses, our model consists of a system of equations wherein error terms across the equations could be correlated. In systems of equations like this, estimating each equation separately using OLS regression will only produce desirable properties if the error terms across equations are uncorrelated (Kmenta, 1986). To account for this possible error term correlation, we estimated the models using Zellner’s seemingly unrelated regression (SUREG) (Greene, 2000). Hypothesis 2 (H2) proposed that, at team formation, social category diversity would negatively influence both perceived similarity about surface and deep differences. Equations one and four for initial perceived similarity in Table 2 present a test of H2. The coefficient for social category diversity is negative and statistically significant for both perceived similarity about surface differences (b = -5.53, p < .001) and for perceived similarity about deep differences (b = - 0.87, p < .01), supporting H2. -------------------------------------Insert Table 2 about here -------------------------------------Hypothesis 3 (H3) proposed that once a team interacts, deep differences increase conflict. Equations two and five for conflict in Table 2 present a test of H3. The coefficients for 16 informational diversity and value diversity are positive and significant for both perceived similarity about surface differences (b = 2.13, P < .01, and b = 3.76, p < .05) and for perceived similarity about deep differences (b = 2.14, p < .01, and b = 3.72, p < .05), supporting H3. Hypothesis 4 (H4) proposed that conflict reduces final perceived similarity about deep differences. Equation six for final perceived similarity about deep differences in Table 2 presents a test of H4. The coefficient for conflict is negative and statistically significant (b = -0.82, p < .001), supporting H4. Hypothesis 5 (H5) proposed that initial perceived similarity influences final perceived similarity about both surface and deep differences. Equations three and six for final perceived similarity in Table 2 present a test of H5. The coefficient for initial perceived similarity is positive and significant for both final perceived similarity about surface differences (b = .60, p < .001) and final perceived similarity about deep differences (b = .83, p < .001), supporting H5. DISCUSSION AND CONTRIBUTIONS Prior research presumed perceived similarity to be static during the time a team is together. The results of our study suggest otherwise. Initial perceived similarity about both surface and deep differences, in teams of unfamiliar members, is based on social category diversity. Visible demographic information at team formation fuels social categorization processes causing team members to form stereotypical behavioral expectations of, and in-group relationships with, each other (Elsass & Graves, 1997). Teams with higher social category diversity have lower initial perceived similarity about both surface and deep differences. Furthermore, informational and values diversity were associated with increased conflict during team interactions and subsequently with reduced final perceived similarity about deep differences. In fact, perceived similarity about deep differences decreased more than perceived similarity about surface differences in our sample, 17 suggesting that team members do update their initial assumptions about underlying individual differences once they begin to interact and learn more about each other. Our results have several implications for future research on diversity in teams. They are consistent with the results of other studies that have moved beyond an exclusive emphasis on demographic characteristics to include “deeper” forms of diversity as predictors of team perceptions and outcomes (Harrison et al., 1999; Harrison et al., 2002; Jehn et al., 1999), a step that cannot be ignored by future research addressing questions about the complex relationship between team diversity and performance. Our findings also extend research on the longitudinal effects of team diversity (Watson et al., 1993). By establishing that perceived similarity varies over time, this research offers intriguing clues as to why empirical findings on diversity and team effectiveness are mixed. Previous research has not fully attended to the temporal dynamics of diversity in teams and, therefore, has cast perceived similarity as a static construct, an assumption we now know to be false. As an emergent state, perceived similarity is a product of diversity and team experiences, and changes over time as experiences vary. Emergent states become inputs into subsequent team processes and outcomes (Marks et al., 2001). Therefore, any conclusions reached about diversity and perceived similarity in teams need to be qualified by the time point of measurement in a team’s life. Future research on diversity and perceived similarity in teams should consider temporal aspects to assure that important theoretical relationships are accurately identified (Mitchell & James, 2001). Although perceived similarity changes over time, we also found that initial perceived similarity still influences final perceived similarity, suggesting that initial categorizations based on social category differences among team members bias and anchor their perceptions of team diversity. This finding is consistent with research on the establishment of routines in teams, which emphasizes the crucial role of “early interaction” in setting the stage for subsequent team performance (Gersick & Hackman, 1990). Future research on teamwork should consider the 18 significance of initial impressions of team diversity by recognizing the automatic formation processes of perceived similarity and planning interaction at the early stages of team development to emphasize or de-emphasize the salience of certain attributes. While some individual differences among team members are immutable, it is possible to change perceived similarity in teams. For example, at team launch, team leaders might detail common backgrounds, training, and personal goals to supplement surface diversity information that team members automatically attend to. Pointing out commonalities may be more important if a team has high variance in surface diversity, so managers should determine if it would be beneficial to develop higher perceived similarity to aid in team integration. Simply understanding this fact should motivate both researchers and managers to discover new approaches to team formation that promote a “positive perception cycle,” perhaps by emphasizing common goals and the shared organizational memberships of team members. Conflict precipitates subsequent updates of perceived similarity about deep differences. We theorized that conflict acts as a carrier of information about team diversity, revealing underlying differences in information and values among team members. Conflict may offer another possibility for influencing perceived similarity in teams. Indeed, our study provides a different perspective on conflict than previously established in the literature on diversity in teams. Past research has consistently framed conflict as an outcome of team diversity (e.g., Jehn et al., 1999). While our results support this perspective, they also suggest that conflict acts as a carrier of information about deep diversity. Conflict, or the lack thereof, influences perceptions of team diversity by reinforcing or undermining initial stereotypical assumptions about underlying individual differences. Therefore, the effective management of conflict may be another way to promote a “positive perception cycle” and enhance group development in diverse teams. For example, conflict can be expressed in different ways. Open task conflict involving disagreement may more strongly decrease perceived similarity than other methods of raising disagreement. Constructive controversy is a group process 19 technique wherein members use respectful communication to raise opinions and have norms of careful listening to alternative viewpoints (Alper, Tjosvold & Law, 1998). Training teams in these techniques may enable them to benefit from the value of their diverse viewpoints without risking the reduction in social integration that may occur if perceived similarity is reduced by open task conflict. From a practical standpoint, our results reinforce the idea that managers must exercise great care in forming and designing teams. Particular attention should be given to highlighting similarities among members during early interactions in diverse teams. We are not saying that individual differences should be muted, but rather that initial assessments of team diversity should be tempered by more explicit information about the homogeneity of team members so that initial perceived similarity is not biased by the salient social category diversity of the team. In essence, we are advocating for managers to create an environment in which team members are initially focused on their similarities, leading to positive social integration and group identification and potentially enabling team members to better manage conflict that may emerge as their underlying individual differences manifest during team interactions. In fact, a heightened sense of in-group membership at team formation could actually cause team members to minimize emerging differences and anchor subsequent perceptions of similarity. Limitations & Concluding Comments Although our research design and analyses provide a rigorous test of our hypotheses, all studies are limited in some respects. While the teams in our sample consisted of adults working on multiple group projects that affected their grades, and therefore other personal goals and outcomes, the external validity of our findings can only be verified through replication in workforce teams. Having said that, there are some important characteristics of our design that could be difficult to replicate elsewhere. Our ability to control data collection that corresponded immediately with team formation allowed us to isolate more clearly the formation of initial perceived similarity. Finding a 20 similar cohort of teams at this point of team development in other field settings would be difficult, and experimental designs including multiple projects over more than sixteen weeks are similarly improbable. Thus, while the use of student teams may limit some generalizability of our results, this sample allowed us to isolate and study the phenomena that we set out to investigate. Survey length restrictions and limitations on the availability of archival diversity data restricted the types of diversity that we could investigate. While we did include multiple types of diversity (social category, informational, and values) in our study, other forms of diversity might also be important in determining perceived similarity in this and other samples. Future research should include additional analysis of what forms of diversity are salient in different settings, since processes of self-categorization have a situation base, meaning that the characteristics that are most salient to a team might vary across different contextual situations (Fiske & Taylor, 1991). In conclusion, our study adds to the literature on diversity in teams by contributing additional knowledge about perceived similarity in diverse teams. In particular, we illustrate how perceived similarity, as an “emergent state,” forms and changes during a team’s time together. We hope that the results of this research pique the interest of other scholars to follow the path we have taken and to continue developing an understanding of the dynamic nature of group perceptions and the role that they may play in translating diversity into team action. 21 REFERENCES Allport, G. 1954. The Nature of Prejudice. New York: Addison-Wesley. Asch, S. E. 1946. Forming impressions of personality. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 41, 1230-1240. Alagna, S., Reddy, D.M., & Collins, D.L. (1982). Perceptions of functioning in mixed-sex and male medical training groups. Journal of Medical Education, 57, 801-803. Alper, S., Tjosvold, D., & Law, K. (1998). Interdependence and controversy in group decision making: Antecedents to effective self-managing teams. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 74, 33-52. Ambady, N. & Rosenthal, R. 1992. Thin slices of behavior as predictors of interpersonal consequences: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 2: 256-274. Ashforth, B. E. & Mael, F. 1989. Social identity theory and the organization. Academy of Management Review, 14(1), 20-39. Bentler, P. M. 1990. Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychological Bulletin, 107: 238-246. Brewer, W. (1987). Schemas versus mental models in human memory. In P. Morris (Ed.) Modeling cognition. Oxford: John Wiley & Sons. Brewer, M.B., Manzi, J.M., & Shaw, J.S. 1993. In-group identification as a function of depersonalization, distinctiveness, and status. Psychological Science, 4: 88-92. Burke, M.J. & Dunlap, W.P. 2002. Estimating interrater agreement with the average deviation index: A user’s guide. Organizational Research Methods, 5: 159-172. Byrne, D. 1971. The Attraction Pardigm, New York: Academic Press. Chattopadhyay, P. 1999. Beyond direct and symmetrical effects: The influence of demographic dissimilarity on organizational citizenship behavior. Academy of Management Journal, 42: 273-287. Byrne, D. 1971. The attraction paradigm. New York: Academic Press. Chattopadhyay, P. 1999. Beyond direct and symmetrical effects: The influence of demographic dissimilarity on organizational citizenship behavior. Academy of Management Journal, 42: 273-287. Dunlap, W.P., Burke, M.J. & Smith-Crowe, K. 2003. Accurate tests of statistical significance for r(WG) and average deviation interrater agreement indices. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(2), 356362. Earley, P. C. & Mosakowski, E. 2000. Creating hybrid team culture: An empirical test of international team functioning. Academy of Management Journal, 43: 26-49. Elsass, P.M., & Graves, L.M. 1997. Demographic diversity in decision-making groups: The experiences of women and people of color. Academy of Management Review, 22: 946-973. 22 Festinger, L. 1954. A theory of social comparison processes. Human Relations, 7: 117-140. Fiske, S. T. & Taylor, S. E. 1991. Social Cognition, 2nd Edition, McGraw-Hill, New York. Gersick, C. & Hackman, J. R. 1990. Habitual routines in task performing groups. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 47: 65-97. Glick, W. H. 1985. Conceptualizing and measuring organizational and psychological climate: Pitfalls in multilevel research. Academy of Management Review, 10: 601-616. Greene, W. H. 2000. Econometric Analysis. 4th Edition. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall. Griffith, T. L., & Neale, M. A. (2001). Information processing in traditional, hybrid, and virtual teams: From nascent knowledge to transactive memory. In B. M. Staw & L. L. Cummings (Eds.), Research in Organizational Behavior (Vol. 23, pp. 379- 421). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press. Grieve, P. G., & Hogg, M. A. 1999. Subjective uncertainty and intergroup discrimination in the minimal group situation. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 25: 926-940. Harrison, D. A., Price, K. H., & Bell, M. P. 1998. Beyond relational demography: Time and the effects of surface- and deep-level diversity on work group cohesion. Academy of Management Journal, 41: 96-107. Harrison, D. A., Price, K. H., Gavin, J. H. & Florey, A. T. 2002. Time, teams, and task performance: Changing effects of surface- and deep-level diversity on group functioning. Academy of Management Journal, 45(5) 1029-1045. James, L.R., Demaree, R.G. & Wolf, G. 1984. Estimating within-group interrater reliability with and without response bias. Journal of Applied Psychology, 69: 85-98. Jehn, K. A. 1995. A multi-method examination of the benefits and detriments of intragroup conflict. Administrative Science Quarterly, 40: 256-282. Jehn, K. A. 1997. A qualitative analysis of conflict types and dimensions in organizational groups. Administrative Science Quarterly, 42: 530-557. Jehn, K. A., Chadwick, C. & Thatcher, S. M. B. 1997. To agree or not to agree: The effects of value congruence, individual demographic dissimilarity, and conflict on workgroup outcomes. International Journal of Conflict Management, 8: 287-305. Jehn, K. A., Northcraft, G. B., & Neale, M. A. 1999. Why differences make a difference: A field study of diversity, conflict, and performance in work groups. Administrative Science Quarterly, 44: 741763. Kahneman, D. & Tversky, A. (1979). Prosepct theory: An analysis of decision-making under risk. Econometrica, 47, 263-292. 23 Klein, K.J., & Koslowski, S. W. J. 2000. Multi-level theory, research, and methods in organizations: Foundations, extensions and new directions. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Kmenta, J. 1986. Elements of Econometrics (2nd ed.). New York: Macmillan Publishing. Lau, D. C. & Murnighan, J. K. 1998. Demographic diversity and faultlines: The compositional dynamics of organizational groups. Academy of Management Review, 23(2): 325-330. Lindell, M.K., Brandt, C.J., & Whitney, D.J. 1999. A revised index of interrater agreement for multiitem ratings of a single target. Applied Psychological Measurement, 23: 127-135. Marks, M.A., Mathieu, J.E., & Zaccaro, S.J. 2001. A temporally-based framework and taxonomy of team processes. Academy of Management Review, 26: 356-376. McBer & Company. Personal Values Questionnaire, Training Resources Group, Boston: Massachusetts. Milliken. F. J., & Martins, L. L. 1996. Searching for common threads: Understanding the multiple effects of diversity in organizational groups. Academy of Management Review, 21: 402-433. Mitchell, T. & James, L. R. 2001. Building better theory: Time and the specification of when things happen. Academy of Management Review, 26: 530-547. Mullin, B-A., & Hogg, M. A. 1998. Dimensions of subjective uncertainty in social identification and minimal intergroup discrimination. British Journal of Social Psychology, 37 345-365. O'Reilly, C., Williams, K., & Barsade, S. (1998). Group demography and innovation: Does diversity help? In D. Gruenfeld (Ed.), Composition. US: Elsevier Science/JAI Press. Pelled, L. 1996. Demographic diversity, conflict, and work group outcomes: An intervening process theory. Organization Science, 7: 615-631. Pelled, L. H., Eisenhardt, K. M., & Xin, K. R. 1999. Exploring the black box: An analysis of work group diversity, conflict, and performance. Administrative Science Quarterly, 44: 1-28. Pfeffer, J. 1983. Organizational demography. In L. L. Cummings and B. M. Staw (eds.), Research in Organizational Behavior, 5: 299-357. Greenwich, CT: JAI Press. Polzer, J. T., Milton, L. P. & Swann, W. B., Jr. 2002. Capitalizing on diversity: Interpersonal congruence in small work groups. Administrative Science Quarterly, 47: 296-324. Riordan, C. M. 2000. Relational demography within groups: Past developments, contradictions, and new directions. In G. R. Ferris (Ed.), Research in Personnel and Human Resources Management, 19: 131173. Greenwich, CT: JAI Press. Secord, P. F. & Backman, C. W. 1964. Interpersonal congruence, perceived similarity, and friendship. Sociometry, 27(2), 115-127. 24 Shaver, K. G. 1975. An introduction to attribution processes. Cambridge, MA: Winthrop Publishers, Inc. Tajfel, H. 1978. Differentiation between social groups. New York: Academic Press. Tajfel, H. & Turner, J. 1986. The social identity theory of intergroup behavior. In S. Worchel & W. G. Austin (Eds.), The social psychology of intergroup relations, 7-24, Chicago: Nelson-Hall. Teachman, J. D. 1980. Analysis of population diversity. Sociological Methods and Research, 8: 341-362. Turner, J. C., Hogg, M. A., Oakes, P. J., Reicher, S. D., & Wetherell, M. S. 1987. Rediscovering the social group: A self-categorization theory. Oxford: Blackwell. Watson, W. E., Kumar, K. K., & Michaelson, L. K. 1993. Cultural diversity’s impact on interaction process and performance: Comparing homogeneous and diverse task groups. Academy of Management Journal, 36: 590-602. Williams, K. Y., & O’Reilly, C. A., III. 1998 Demography and diversity in organizations: A review of 40 years of research. Research in Organizational Behavior, 20: 77-140. 25 TABLE 1 Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Coefficientsa (n=25 teams) Mean s.d. 10 11 Variables 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 1. T1 P Similarity Surface 2.78 1.73 1.00 2. T1 P Similarity Deep 3.81 0.84 0.71 1.00 3. T3 P Similarity Surface 2.62 1.51 0.95 0.63 1.00 4. T3 P Similarity Deep 3.25 0.92 0.70 0.73 0.62 1.00 5. T2 Meeting Frequency 3.48 0.75 0.22 0.36 0.11 0.20 1.00 6. T3 Meeting Frequency 4.53 0.63 -0.03 -0.01 0.10 -0.17 0.25 1.00 7. T2 Conflict 2.53 0.57 -0.33 -0.45 -0.28 -0.52 -0.07 0.06 1.00 8. Social Category Diversity (Surface) 0.60 0.23 -0.81 -0.37 -0.85 -0.50 -0.02 0.02 0.16 1.00 9. Informational Diversity (Deep) 0.93 0.12 -0.07 -0.17 -0.01 -0.18 0.21 0.23 0.44 -0.04 1.00 10. Value Diversity (Deep) 0.14 0.04 -0.17 -0.20 -0.19 -0.05 -0.19 -0.28 0.32 0.07 -0.15 1.00 0.07 1.00 11. Team Size 5.37 0.57 -0.12 -0.10 -0.20 -0.10 0.28 -0.10 -0.03 0.01 0.25 0.11 12. Class Year 0.52 0.51 -0.52 -0.72 -0.50 -0.49 -0.19 0.04 0.17 0.26 0.21 -0.12 a For correlations with absolute values greater than or equal to 0.49, p .05 and with absolute values greater than or equal to 0.52, p .01. 26 TABLE 2 S.U.R.E. Regression Results (n=25 teams) Perceived Similarity: Surface Equation 1: Equation 2: Equation 3: Initial Perceived Conflict Final Perceived Similarity (T2) Similarity (T1) (T3) Team Size -0.18 (0.27) -1.12 (0.31) Class Year *** T2 Meeting Frequency -0.13 (0.15) -0.06 (0.20) -0.01 (0.13) -0.25 (0.16) -0.16 (0.21) T3 Meeting Frequency Social Category Diversity (Surface) Informational Diversity (Deep) Value Diversity (Deep) 0.24 (0.14) -5.53 (0.64) *** -0.60 (1.31) -4.03 (3.77) 0.20 (0.76) 2.13 (0.74) 3.76 (20.9) Initial Perceived Similarity Surface (T1) -1.45 (0.71) ** * -0.05 (0.12) Initial Perceived Similarity Deep (T1) 0.65 (0.87) -1.32 (2.34) 0.60 (0.11) -0.87 (0.36) ** -0.26 (0.75) -3.24 (2.14) 0.42 (0.40) 2.14 (0.74) 3.72 (2.11) -0.36 (0.48) ** * .83 122.55 *** .37 14.83 * Standard errors are in parentheses. -0.07 (0.21) .93 326.70 1.03 (1.05) 3.62 (2.87) *** -0.07 (0.22) Conflict (T2) R2 Chi-Square * Perceived Similarity: Deep Equation 4: Equation 5: Equation 6: Initial Conflict Final Perceived Perceived (T2) Similarity Similarity (T3) (T1) -0.05 -0.12 -0.06 (0.16) (0.15) (0.19) -1.04 *** -0.08 0.19 (0.26) (0.32) -0.01 (0.14) -0.18 (0.17) *** .70 58.34 *** .37 14.72 * 0.83 (0.24) -0.82 (0.25) .72 63.38 *** *** *** + p < .10, * p < .05, ** p < .01, *** p < .001 27 FIGURE 1 Summary of Hypothesized Relationships Between Types of Diversity, Perceived Similarity, and Conflict T1 Surface Diversity >Social Category - Initial Perceived Similarity + Final Perceived Similarity Deep Diversity >Informational >Values + Conflict - T2 T3 28