08. The Punic Wars

advertisement

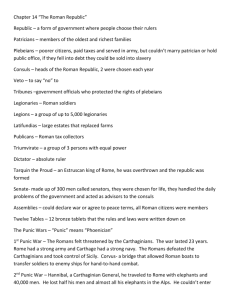

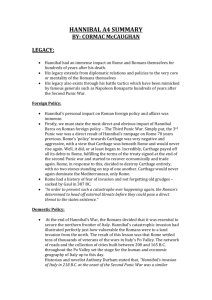

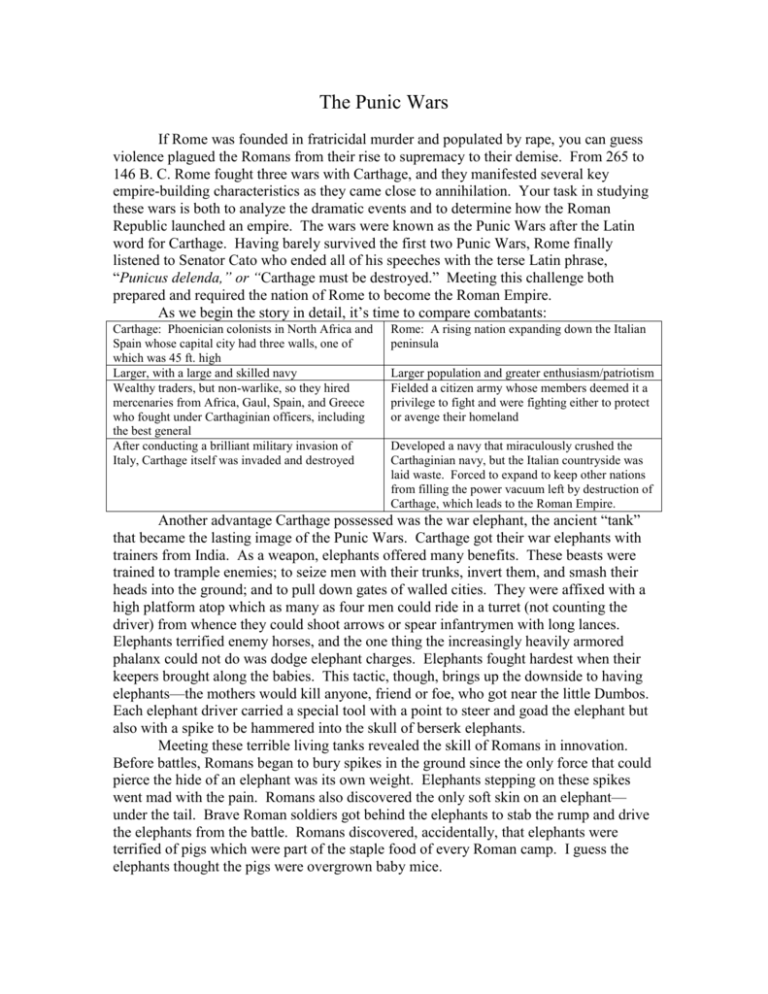

The Punic Wars If Rome was founded in fratricidal murder and populated by rape, you can guess violence plagued the Romans from their rise to supremacy to their demise. From 265 to 146 B. C. Rome fought three wars with Carthage, and they manifested several key empire-building characteristics as they came close to annihilation. Your task in studying these wars is both to analyze the dramatic events and to determine how the Roman Republic launched an empire. The wars were known as the Punic Wars after the Latin word for Carthage. Having barely survived the first two Punic Wars, Rome finally listened to Senator Cato who ended all of his speeches with the terse Latin phrase, “Punicus delenda,” or “Carthage must be destroyed.” Meeting this challenge both prepared and required the nation of Rome to become the Roman Empire. As we begin the story in detail, it’s time to compare combatants: Carthage: Phoenician colonists in North Africa and Spain whose capital city had three walls, one of which was 45 ft. high Larger, with a large and skilled navy Wealthy traders, but non-warlike, so they hired mercenaries from Africa, Gaul, Spain, and Greece who fought under Carthaginian officers, including the best general After conducting a brilliant military invasion of Italy, Carthage itself was invaded and destroyed Rome: A rising nation expanding down the Italian peninsula Larger population and greater enthusiasm/patriotism Fielded a citizen army whose members deemed it a privilege to fight and were fighting either to protect or avenge their homeland Developed a navy that miraculously crushed the Carthaginian navy, but the Italian countryside was laid waste. Forced to expand to keep other nations from filling the power vacuum left by destruction of Carthage, which leads to the Roman Empire. Another advantage Carthage possessed was the war elephant, the ancient “tank” that became the lasting image of the Punic Wars. Carthage got their war elephants with trainers from India. As a weapon, elephants offered many benefits. These beasts were trained to trample enemies; to seize men with their trunks, invert them, and smash their heads into the ground; and to pull down gates of walled cities. They were affixed with a high platform atop which as many as four men could ride in a turret (not counting the driver) from whence they could shoot arrows or spear infantrymen with long lances. Elephants terrified enemy horses, and the one thing the increasingly heavily armored phalanx could not do was dodge elephant charges. Elephants fought hardest when their keepers brought along the babies. This tactic, though, brings up the downside to having elephants—the mothers would kill anyone, friend or foe, who got near the little Dumbos. Each elephant driver carried a special tool with a point to steer and goad the elephant but also with a spike to be hammered into the skull of berserk elephants. Meeting these terrible living tanks revealed the skill of Romans in innovation. Before battles, Romans began to bury spikes in the ground since the only force that could pierce the hide of an elephant was its own weight. Elephants stepping on these spikes went mad with the pain. Romans also discovered the only soft skin on an elephant— under the tail. Brave Roman soldiers got behind the elephants to stab the rump and drive the elephants from the battle. Romans discovered, accidentally, that elephants were terrified of pigs which were part of the staple food of every Roman camp. I guess the elephants thought the pigs were overgrown baby mice. Having said all that, let’s commence the First Punic War. Hostility opened up slowly over Sicily which lay between Carthage and Rome in the Mediterranean Sea. Rome had advanced all the way down the boot until it was staring at a Carthaginian garrison across the water in Sicily. Sicily appealed to Rome for protection, and the Roman Senate seized this request as a good excuse. Rome built a fleet of ships supposedly by using a stranded Carthaginian ship as a model. Through trial and error and brilliant innovation, this first fleet secured Rome’s first naval victory in 260 B. C. The innovation came from knowing that Rome’s chief strength was in its infantrymen. A Roman naval commander designed the corvus, or the Raven, a swiveling gangway mounted on the front of Roman ships and maneuvered by ropes coming from the central mast. The Romans used the Raven to turn sea battles into land battles. They deployed the gangway, and 120 legionnaires stormed onto enemy ships and slaughtered the stunned enemy sailors. 31 Carthaginian ships were captured intact. Many others were destroyed. Then in 256 B. C. Rome sent more ships to conquer a new Carthaginian fleet off the Sicilian coast in the largest naval battle in history to that time. The Raven won again. Next, Rome landed for the first time on Carthaginian soil with intentions of conquering the city of Carthage. Instead, the Roman army was driven into the sea by fierce resistance. Only a few Romans survived to return to the Senate with the news. The First Punic War closed having established a deadly pattern. A clash would erupt between the two powers, one side would be massacred, and then both sides would rebuild to clash again. By 241 B. C. the First Punic War ended in a truce in which Sicily was granted to Rome. Losing any territory to the accursed Romans was intolerable to many Carthaginians, but especially to a particular family ruling Spain for Carthage. Enter the Barca family. Hannibal Barca and his younger brother Hadsdrubal were raised by their father, Hamilcar, in Spain of which their father was the governor. Hamilcar took charge of Spain (the Iberian Peninsula) and in only eight years built up a stable state, a full treasury, and an impressive army. He staged a ceremony where he made Hannibal vow at the age of nine to be the “implacable enemy of Rome.” When Hamilcar died Hannibal became the governor of Spain at age 26. To fulfill the vow to his father, Hannibal relentlessly marauded around the Italian Peninsula terrorizing the Romans in the Second Punic War which lasted from 218-202 B. C. His exploits proved him to be one of the greatest generals in history. We only know of the attributes and exploits of Hannibal from the writings of his enemies which made it all the more remarkable that he was known as the best general of his age. Of his appearance all that is recorded is that he was lean, hard-muscled, with piercing eyes. His enemies said he personified power and labeled him Rome’s worst nightmare. Hannibal spoke and wrote both Latin and Greek, and as a general he was a psychologist who outguessed his enemies as long as he had correct information. To secure correct information, he used scouting and spying which the Romans did not (until they learned how from Hannibal). To secure absolutely correct information, Hannibal sometimes disguised himself and did his own spying. When he got to Italy, Hannibal unleashed such terrible havoc that wounded Roman soldiers often smothered themselves to death by burying their faces in the dirt to avoid dying in a manner determined by this enemy. Legends said that Roman statues sweat blood when Hannibal drew near, and Roman cows uttered prophesies of doom with human voices. These are the tales of a people who have been deeply spooked. How Hannibal got into Italy is part of the drama of his persona. On a long march Hannibal crossed the Pyrenees Mountains out of Spain with about 25,000 men and about a dozen war elephants. Boldly, he cut off communication with Carthage and lived off the land for the five-month journey to the Italian Alps. He marched four more days past a fortified Roman pass, and then marched his army with elephants up and over the Alps in a crossing that took fifteen days. The conditions were so rugged that he lost one quarter of his men. When peaks seemed impassable, Hannibal had his men and elephants build huge fires and then pour wine on the superheated rocks, cracking them and opening up his own pass. He entered Italy and began a war that would last for fifteen years. Now commences the parade of Consuls to their demise. Publius Cornelius Scipio was the first Roman Consul to meet Hannibal in northern Italy in 218 B. C. Scipio’s attack was repulsed and he himself was wounded. The other Consul, Tiberius Sempronius Longus, took over. Remember, the Consulate was an annually elected position in the Roman Republic, and Hannibal went through about a dozen of them. Longus lost 2/3 of his men on the Trebia River where the psychological general had staged a cavalry ambush. The Roman horses were terrified by the elephants. Hannibal’s “tanks” were a huge advantage at first, but war or winter temperatures killed all the elephants eventually except one which Hannibal personally rode. Accounts of the Second Punic War say he was blinded in one eye and wanted the visual advantage the elephant’s height provided. Still there had not been a major battle. The first was at Lake Trasimene in 217 B. C., closer to Rome. Hannibal met a new Consul, Gaius Flaminius, and lured him into a natural deathtrap. While scouting, Hannibal found a pocket of level ground between the lake and the surrounding bluffs. He timed an ambush perfectly so that mists rising from the lake would hide a cavalry charge pouring down the bluffs, gaining speed across the level patch, and attacking the unsuspecting Romans. The Roman soldiers were merely marching when they were driven into the lake. Two whole legions were annihilated. Fifteen thousand Roman soldiers were killed and ten thousand surrendered while Hannibal lost only 2,500 men. Hannibal ambushed the other new Consul, too, and killed four thousand cavalry in that attack. Rome was terrified, so terrified that they permitted the election of a dictator, Quintus Fabius Maximus. Hannibal sought new recruits. Hannibal gained soldiers from Gaul and a few from Italy. Maximus refused to be lured into battle, so Hannibal merely ravaged the countryside like the Spartans did in the Peloponnesian War. Not only was he trying to force a battle with Maximus, Hannibal had to feed his army on the spoils. Romans eventually realized the dictator wasn’t going to do anything, so they went back to Consuls again. The second major battle of the Second Punic War was Hannibal’s greatest victory. In 216 B. C. one Consul, Paullus, said “Go!” The other, Varro, said, “No!” But the battle was joined at Cannae. Hannibal defeated both overwhelmingly despite being outnumbered. Rome fielded eight legions, or 40,000 infantrymen along with 40,000 allied foot soldiers. They had 6,000 cavalry troops for a total of 86,000 combatants. Hannibal could only muster 56,000 total troops with only 45,000 infantrymen. His advantage was in having 11,000 cavalry and in his position he had chosen on the field through scouting. The wind was at the backs of the Carthaginian army, so as they advanced, all the dust of their movement blew into the Roman army’s eyes. Hannibal also borrowed the strategic retreat and pincer movement strategies of the Athenians at the Battle of Marathon. He led the center of his line personally in advancing faster than the rest of his army. When this center met the enemy, they feigned retreat and fell back, flattening their lines and then actually bowing the line backward. Meanwhile, Hadsdrubal commanded the cavalry which was divided in two on the flanks. As their superior numbers drove away the Roman cavalry, the Carthaginian horsemen were able to fold in on either side of the Roman army in a vast, pre-arranged pincer movement. A final ploy was designed by Hannibal with 500 fierce Numidian mercenaries. These men, on Hannibal’s orders, pretended to defect to the Roman side by throwing down their weapons. When in the rear as prisoners, the Numidians took out new weapons they had hidden under their clothing and attacked with Hadsdrubal from the rear. 45,500 Roman infantry lay dead when the dust settled along with 2,700 dead Roman cavalrymen and Paullus, the Consul who had argued for making the attack at Cannae. Hannibal lost fewer than 8,000 men. Further Romans were taken captive and sacrificed “by the hundreds to hideous gods,” as the account goes. In desperation Rome made its first smart move. The Senate dispatched legions to all surrounding points to prevent Hannibal from gaining significant reinforcements hoping to win by attrition since they could not beat Carthage in battle. And Rome never gave up hope. The Senate thanked Varro after Cannae for not committing suicide, “for not having despaired of the salvation of the country.” But Rome was about to collapse. Large sections of Italy began to defect to Carthage. Capua was besieged by Rome for defection, and Hannibal tried to divert the Romans by marching on Rome itself, but Rome’s walls proved impregnable. Plus, another general named Publius Cornelius Scipio, the son of the first Scipio who had died of his wounds at the beginning of the war, was beginning to show himself to be Rome’s best general. He had gone to Spain and captured New Carthage, but he could not prevent Hannibal’s brother Hadsdrubal from returning with reinforcements to help Hannibal win Cannae. After Cannae, Hadsdrubal went back to Gaul to get more reinforcements. He was caught on his way at the Metaurus River by two Consuls at once and killed. A message sent to Hadsdrubal from Hannibal was then intercepted, so the Consuls kept their armies combined and for once surprised Hannibal. Therefore, Hannibal met an army twice as large as he anticipated and met with his first defeat at Nola in 215 B. C. The first news he had of his brother’s death was Hadsdrubal’s head being thrown into his camp by a catapult. Carthage recalled Hannibal because Scipio Africanus was about to win his nickname by out-Hannibal-ing Hannibal and invading Carthage itself. The third major battle of the Second Punic War was Zama, in 202 B. C., when Hannibal arrived at home to repel the Roman invasion. Before we analyze that battle and Hannibal’s undoing, though, we should look at the three miscalculations on the part of this military genius that led to his downfall. One, Gauls (later the French) made fickle allies. Two, Hannibal’s original plan may have been flawed because he lost too many men from his original army while crossing the Alps. Three, he misjudged Rome and believed more Italians would revolt and join him. This last is understandable because Carthage brutally oppressed their conquered subjects. Hannibal did not realize until it was too late one of the distinguishing empire-building characteristics of Rome, the Romans helped the people they conquered. The lives of Italians unified under the Roman Republic were improved, so few ever revolted. This phenomenon was beyond Hannibal’s ken. Now, to return to the climax of our story, Hannibal arranged what he thought was an invincible force to protect his home city-state. 37,000 Infantry met only 30,000 of Scipio’s soldiers, and Rome had an advantage this time in 7,000 cavalrymen to Carthage’s 5,000. Hannibal had eighty war elephants, though. Scipio Africanus, however, had devised a strategy to eliminate the elephant threat. He arranged his troops in a solid line on the front but with lanes behind the first few soldiers. When the elephants charged, Roman soldiers shouted and blew trumpets to disorient them, then opened up the disguised lanes. The maddened elephants charged right down the lanes with Roman soldiers goading them from behind and driving them right off the battlefield! The Roman cavalry, because of its superior numbers, then drove Hannibal’s cavalry away. As these unforeseen circumstances unfolded, the first line of Hannibal’s troops retreated. As they were not allowed to fall straight back, they ran to the flanks and back. The second line did likewise leaving Hannibal’s center unintentionally weak. Still Hannibal kept his troops together and matched the Roman onslaught until the Roman cavalry returned and attacked from the rear in an almost exact duplication of Hannibal’s own strategy that won at Cannae. 25,000 Carthaginian troops were killed and 10,000 were captured with only 5,000 Roman deaths. Hannibal escaped and asked for peace. Scipio Africanus proved that he was the first Roman general who could learn. Roman generals kept on learning from that point until they had conquered the known world. Rome disgraced Carthage by towing her entire navy into their harbor and burning it. Carthage was only allowed to retain the land right around them in Africa. The rest of Carthage’s empire became the first large expansion of the Roman Empire. Hannibal tried to stabilize Carthage to renew the war and live up to the vow he made his father. Rome ordered his arrest for breaking the truce, but he escaped again. In search of allies against Rome, he helped King Antiochus of Syria before again facing arrest. When no avenues presented themselves, Hannibal, the greatest general of his age, took poison and died in 183 B. C. As Rome began to fabricate the machinery of running an empire, Cato began ending his speeches in the Senate as indicated earlier by urging the final destruction of Carthage. The Senate agreed in 149 B. C. and invaded Carthage a second time to start the Third Punic War. By 146 B. C. the city-state of Carthage was erased and Roman armies salted the ground. Rome was left in control of the entire Mediterranean area. Only one other man of which I am aware was ever memorialized by the mothers of his enemy as was Hannibal by the mothers of Rome. They used fear of him to discipline their children. In like manner, Muslim mothers in Palestine after the Crusades would tell their children, “Richard the Lion-hearted will get you!” This phenomenon is called “grudging respect.” You babysitters might want to try it, too. Assignment: You are to create what I call an annotated timeline. Start with a basic timeline drawn across or down the middle of two or three pages in your notebook (orient the timeline however you desire: lengthwise, top to bottom, diagonally, etc.). Place all of the key dates on the timeline along with labels explaining what event made each date important, i.e. “The Battle of Zama.” Use the rest of your blank space on your paper, however, to annotate and illustrate the sequence of events. This means to provide explanatory notes with perhaps a few drawings along the length of your timeline that record the key details necessary to understand the Punic Wars. For example, when Hannibal first arrives on your timeline, list his distinguishing attributes near the spot on your timeline. Summarize key battles. Explain cause/effect relationships. Thoroughly use all the space to portray the content of this article in a complete, correct, and complex manner on two or three pages of your notebook. When finished, leave a little room to list 4-5 key Roman empire-building qualities that their civilization exhibited in this experience.

![[1] - RedfieldAncient](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/006748961_1-cfd86e6af3cd1ec34f89f33ab16fc864-300x300.png)