NataleeSteffen

advertisement

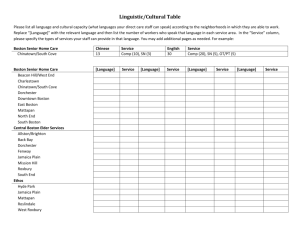

Boston Against Busing; Race, Class, and Ethnicity by Ronald P. Formisano A Book Review by Natalee Steffen March 2009 Is Boston a Racist City? The 1954 Supreme Court case of Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka declared racial segregation a violation of the Fourteenth Amendment – ultimately stating that “separate educational facilities are inherently unequal”. As a result of this decision, schools across the nation were to integrate – and in the particular case of the Boston Public School System during the 1970s, schools subsequently were to integrate by court ordered busing. Ronald P. Fomisano deals with the Boston public’s candid response to court ordered busing in his book titled, Boston Against Busing: Race, Class, and Ethnicity in the 1960s and 1970s. Unexpectedly, Formisano does not directly sympathize with the black community of Boston throughout the turmoil of this time, but instead argues that those politics which hope to defeat racism do not necessarily consider the social issues of reality. Although unexpected, Formisano provides an interesting look into the emergence of public displays of racism – that which are developed when the traditional lines of social status and ethnic community are crossed. A major concern to consider while examining the outcome of Brown v. Board is de facto segregation due to ethnically divided neighborhoods. The author uses tables and neighborhood maps to illustrate the extent of Boston’s ethnic enclaves throughout the 1960s and 1970s. In 1965 the Boston legislature passed the Racial Imbalance Act to combat this problem. This law defined a racially imbalanced school as one with over 50 percent nonwhite students, and stated that any imbalanced school system could lose state funds. Formisano argues that the theory backing this law coincides well with the Civil Rights Movement at the time, “In focusing on racial imbalance rather than on how schools got that way, the law actually went further than the Brown decision”. (35-36) Nevertheless, the Boston School Committee responsible for carrying out this law intentionally avoided and delayed their obligation to desegregate schools. Formisano states, “For nine years after the passage of the Racial Imbalance Act, the Boston School Committee… refused to takes steps to bring about any significant school integration” (44). In fact, the Boston School Committee passed orders to encourage integration such as an open enrollment policy, but then refused transfers from black students. (37) It is in such cases as these that ultimately drove Judge W. Arthur Garrity, Jr. to his historic resolution holding the Boston School Committee guilty of maintaining a segregated school system. On June 21, 1974 Judge Garrity ordered a busing plan to go into effect that September. (64) It is the reaction to Judge Garrity’s decision that initiates Boston Against Busing’s discussion on race, class, and ethnicity. Formisano labels the outcome of court ordered busing as “Reactionary Populism”. He states, “‘Reactionary Populism’ describes the whole of a movement that included the organized and unorganized, militants and moderates, terrorists as well as middle-class reformists respectful of democratic norms of civility.” (172) The author illustrates the massive amount of organization, demonstration, and protest through the use of photographs. These illustrations of human reaction attest to the idea that populism is traditionally referred to as an uprising of the masses – the lower-class, the working-class, the grassroots of society. Effectively, Formisano refers to “Reactionary Populism” as Boston’s white working-class pitted against those that threatened their traditional social norms – Boston’s collegiate, suburban residing politicians. Through this claim, Boston Against Busing focuses heavily on the politics of the Anti-busing Movement. One significant player was the ROAR (Restore Our Alienated Rights) organization, led by Loiuse Hicks of South Boston. ROAR’s membership consisted primarily of working-class citizens of Boston’s lower to middle-class areas. They began organizing immediately, and on the night of Judge Garrity’s decision, called for a boycott of the schools for the first two weeks in September in protest to the court’s decision. Even though Formisano makes note that ROAR did not encompass all anti-busing activities, I believe that the organization came to be the symbol of “Reactionary Populism”. Additionally, throughout much of his book, Formisano claims a major fault to Judge Garrity’s decision that, as a result, amplified the Anti-busing Movement. Within the first year of the busing plan, the schools ordered to integrate were from two of the neighborhoods most forcefully opposed to busing. These were the Southie and Roxbury neighborhoods of Boston – a white, Irish Catholic working class ghetto and an impoverished black ghetto, respectively. “The state plan that Judge Garrity decided to put into operation in September 1974, requiring the busing of some seventeen to eighteen thousand students…was nonetheless a political and social disaster” (69-70). One can say that the error made by integrating these neighborhoods gave anti-busers grounds to commit violence within the Boston School System. Although everyone expected trouble, most officials trying to keep peace believed that after an initial period of protest the schools – and streets – would settle down. These expectations underestimated the ensuing turmoil – its scope, intensity, and duration. Fights, riots, and protests, in and out of schools, broke out all year long. Racial tensions increased – certainly most Bostonians thought them worse than ever – and violence of white on black and vice versa flared up frequently as a spillover from reactions to desegregation. Throughout the year and beyond a small minority of antibusers conducted what amounted to terrorism against blacks and often whites trying to cooperate, including their own neighbors. (75) Placing no holds on their efforts parents, students, and militants organized to reverse the busing plan within its first year. Consequently, the hate that ran through these neighborhoods eventually became the face of the Anti-busing Movement. Nevertheless, according to Formisano’s argument, the Roxbury and Southie neighborhoods opposed busing not solely because of race, but because someone from the outside was telling them how to live. One thing to consider here is that even though the Racial Imbalance Act served desegregating schools, it never once addressed desegregating neighborhoods. These two neighborhoods disagreed with decisions made by suburban residing politicians, while the Racial Imbalance Act did not extend outside of the city’s limits. Why would a parent want to bus their child across town, when there was a school right near their home? Likewise, we can find a similar approach made in Brown v. Board. Due to Jim Crow Laws, Linda Brown was forced to walk passed her neighborhood school to go to an all black school. How is forced segregation any different than forced integration? When any outsider makes changes on your way of life, it is human nature to place defense barriers up. Furthermore, with the protest era of the 1960s just coming to a close, antibusers were now able to justify their arguments and take action without feeling prohibited to do so. In fact, most parents of Southie were former graduates of South High School themselves, had lived their whole lives within that neighborhood, had great relationships with their old high school friends, continued to wear their letterman jackets, and cherished their high school memories more so than any other. (17) It is not that these anti-busers were outright racist, but were extremely loyal to their neighborhood. These ordinary people felt targeted, which ultimately drove them to defend all they had. With nearly 100 pages of notes, the use of both primary and secondary sources, Formisano solidly presents his argument within Boston Against Busing. One feature I especially think both effective and compelling is the author’s use of sources as an introduction the book’s chapters. In quite a few instances, Formisano sets up his argument with a segment from one or more sources. These segments are sometimes primary and sometimes secondary, sometimes in alignment with the author’s line of reasoning and sometimes not, but whatever the case, they give the people of Boston a voice. This technique allows the reader a chance to preview the author’s sources, and at the same time gives the reader the opportunity to build their own case. Overall, Boston Against Busing was entirely enlightening. I would never have imagined that a city so rooted within the founding ideals of our nation would have had the reaction to integration as it did. I suppose that because I did not grow up in the 1960s or 1970s and did not witness these events first hand I have always assumed that America’s civil rights “problems” primarily took place in the south, and if any did find their way up north they were not significant enough to place any weight on. Furthermore, I’ve presumed that Brown v. Board was the turning point in educational equality between blacks and whites – never realizing that twenty to thirty years later the problem was as strong as ever. This book and its contents would be a wonderful tool to use in the Social Studies classroom – one that I plan to use and one that I recommend to others. Boston Against Busing addresses issues of issues of governance and deviance, issues of class and social structure, issues of education and family life, and most importantly issues involving racial and ethnic conflict in the United States from Reconstruction through contemporary American society. What’s more is that Boston’s Anti-busing Movement proves that these issues took place throughout the nation and not in one single isolated area of our country. Everything considered, Formisano argues that Boston was not a racist city, and that in order to understand the Anti-busing Movement, one must look past racism when examining the resistance to court ordered busing. Judge Garrity and his supporters were attempting to create a peacefully diverse and equally educated society, but the politics that hope to defeat racism do not necessarily consider the social issues of reality.