Update On The 2010 Report From Consumers

advertisement

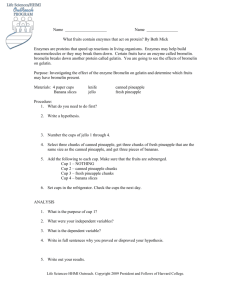

The story behind the Pineapples Sold in Our Supermarkets: The Case of Costa Rica Update on the 2010 Report from Consumers International and Bananalink 1 Contents: Executive Summary 1. Export Data 2. Data on Area under cultivation 3. Key Players and their Certification 4. Impact of the Pineapple Agro-industry in Costa Rica 4.1 Weakening of the small producers sector 4.2 Wages 4.3 Impact on Health 4.4 Unionisation 4.5 Follow-up of workers’ testimony in the 2010 report 4.6 Impact on the community – water pollution in Cairo, Lusiana, and Milano 5. Are good practices being followed in labour relations in the Costa Rican pineapple plantations? 6. National Pineapple Policy Initiative: Platform for the Production and Responsible Trade of Pineapples in Costa Rica 7. Recommendations for Consumer Organisations ANNEX 1: Methodology Followed 2 Executive Summary Since the Consumers International 2010 investigation 'The story behind the pineapples sold on our supermarket shelves; a case study of Costa Rica' there have been a number of changes in the Costa Rican pineapple industry, including: an increase from 75 to 84 percent in Costa Rica's share of the world fresh pineapple market ; a squeeze on producers due to a decrease in the FOB value of pineapple exports to the U.S and Europe, a fall in the value of the Colon and increases in production costs; the emergence of relatively new producers exporting their fruit directly to the European market, such as Chestnut Hill Farms and Orsero; a shift within Fairtrade markets away from the small producers of ASOPROAGROIN (declining sales) to the large-scale Collins Street Bakery/Corsicana (linked to Dole); the emergence of the UNDP/ICCO/IDH backed tripartite initiative 'Platform for Responsible Production and Trade if Pineapple in Costa Rica' ; an increase in the occurrence of direct supermarket certification, in particular Tesco as part of moves to 'cut out the middle man '(the big fruit companies) and establish direct trading relations with national producers. Concerning labour conditions on the plantations – regardless of which producer, exporter or supermarket they are supplying, and which certification schemes these companies are subscribed to workers continue to suffer violations of their basic human rights: exposure to toxic agrochemicals and inadequate provision of protective equipment prevail; wages have risen slightly but have decreased significantly in comparison to the cost of living; anti-union practices such as those promoted by the Solidarismo movement as well as discrimination in the workplace and in hiring policies continue unabated throughout the industry. The tripartite dialogue sought by the National Platform has led to minimal tangible developments for workers due to the lack of involvement of trade unions and workers in this process (labour issues have still not been included on the Platform's agenda) and the unwillingness of CANAPEP (the National Confederation of Pineapple Producers and Exporters) to engage in open dialogue. Costa Rican pineapple production therefore continues to pose a number of serious social and environmental concerns with the only 'ray of light' coming from a small handful of social dialogue initiatives (such as with Corsicana and Dole). However, these limited initiatives have so far created more expectations than they have tangible results. When it comes to establishing a direct linkage between the conditions on the ground for workers and their communities and the policies and certifications of supermarkets at the consumer end of the chain, it remains virtually impossible to get a fully detailed picture from plantation to fruit bowl. The 'bottleneck' of a limited number of packing plants does nothing to assist this investigation, with numerous producers packing their fruit in one central packing plant. This fruit is then branded with equally numerous labels within that one packing plant before being sent to the next stage in the chain, with most commonly no reference whatsoever to the name of the plantation or the producer company. In comparison to the 2010 research, the 2013 European supermarket shelf data indeed shows that the names of the big pineapple brands - Chiquita, Del Monte, Dole and Fyffes -appear less frequently, whilst 3 the names of exporter brands or of the supermarkets themselves appear more frequently. This transition could be considered positive when we take the example of Tesco who are moving towards direct trading relations with producers. More transparent and effective auditing processes in Tesco chains seek to ensure that these new relations with producer partners are based on their ability to supply a product that adheres to the Ethical Trading Initiative's Base Code of labour standards. However, this remains rather a unique case amongst major European retailers. 4 1. Export Data The European supermarket shelf data compliments the Fruitrop 2012 statistics that Costa Rica provides at least 84% of Europe's pineapple imports (in comparison to 75% in 2010) and this share of the market remains on the increase1. Other key supplier countries include, in order of market share, Ghana, Ecuador, Panama and the Ivory Coast. The table below was compiled using the data from the state Trade Promotion Agency - Site PROCOMER http://servicios.procomer.go.cr/estadisticas/inicio.aspx on September 13, 2013. It is based on the three main Costa Rican pineapple export regions. Value of Costa Rican Exports of Pineapples in US $ based on FOB prices from 2009 – 2nd trimester 2013. 2009 2010 2011 2012 260 483,660 157,830 264,265,740 305,032,190 331,205,970 381,778,710 734,540 223,030 57,630 164,440 279,950 130,100 265,057,910 305,419,920 331,969,580 382,066,640 2,960,560 8,258,070 14,506,950 12,944,090 8,258,070 14,506,950 12,944,090 Canned Fresh North America Fresh Organic Dried Total European Non- EU States Fresh 2 0 1 3 * Dry Total 2,960,560 1 Fruitrop October 2012 – No.204 ' Close-up PINEAPPLE' 5 Canned Pineapple EU Organic Dried Total Grand Total 84,870 57,120 30,850 18,310 303,487,050 347,465,820 368,399,870 393,301,270 574,090 124,530 70,390 69,600 89,370 713,790 304,216,400 572,234,870 347,717,070 661,395,050 368,520,090 714,996,620 394,033,370 789,044,100 4 8 2 , 4 6 1 , 9 6 0 Export of fresh pineapples has maintained a steady growth, dried pineapples also especially in the European Union, meanwhile canned pineapples is highly variable in these markets. Particularly striking is the disappearance of organic pineapple exports, which generally involve small and medium sized farmers in the northern region. Since 2009, the FOB value of exports of pineapples has surpassed the export of bananas in the country and pineapple is now Costa Rica’s most important agricultural export. The following table shows tonnage exported, using the same data source. Costa Rican Exports of Pineapples in tonnes from 2009 – 2nd trimester 2013 2009 2010 0 2011 365 2012 86 663,739 777,811 819,859 940,925 1,721 550 7 33 57 32 778,393 820,282 941,043 Canned North America Fresh Fresh Organic Dried Total 665,466 6 European Non- EU States Fresh 5,882 17,990 30,382 28,478 5,882 17,990 30,382 28,478 50 53 19 2 749,643 851,774 882,756 896,789 1,443 354 Dried 283 11 14 115 Total 751,419 852,192 882,789 896,906 Dry Total Canned Pineapple EU Organic Grand Total 1,422,768 1,648,576 1,733,454 1,866,426 The average FOB price per tonne shows price differences between the three export destinations, North America consumes more pineapple, but generates slightly lower income than exports to Europe. Average FOB price per tonne in US$ 2009 North America Non-EU Europe EU Average 2010 398 Average 392 503 Average 459 405 Average 2011 408 402 401 2012 2 0 1 3 * 405 4 1 406 7 477 4 5 455 5 417 4 3 439 9 412 423 The Fruitrop Pineapple Close-up October 2012 explains that 'movements of exchange rates have a strong effect on the value of a kilo of pineapples... A 20% decrease in value in colons of a kilo of pineapple on the European market was observed from 2007 to 2012. Worse still, the US market has fallen in dollars and in colons by respectively 16% and 26% from 2009 to 2012. When it is added that factors of 7 production, and especially those whose price is strongly linked to oil prices (fertilizer, packaging, transport) have increased strongly, it is legitimate to consider that financial returns have decreased distinctly at production. Over the last 12 years inflation in Costa Rica has totally absorbed and even eroded the increase in import prices in Europe and in the United States' In relation to this the former president of CANAPEP (National Chamber of Exporters of Pineapple) Abel Chaves pointed out in an interview, "The appreciation of the colon is hitting us hard. Two years ago we needed to produce about ten boxes to pay a labourer, today it’s between 15 and 18 boxes. " 8 2. Data on Area under Cultivation While information on the increase in area devoted to growing pineapple is unclear, figures from the Costa Rica Chamber of Pineapple Producers and Exporters [Cámara Nacional de Productores y Exportadores de Piña – CANAPEP] indicate that there are approximately 45,000 hectares actively under cultivation, distributed according to breakdowns contained in the report at their disposal. However, the CANAPEP figures also show that 60,000 hectares are not being farmed, either because the land is protected or for other reasons that affect pineapple plantations, most notably pending certification by the Rainforest Alliance and government incentives for forest conservation. Of the total area devoted to growing pineapple, 51% is located in the northern region of the country, where owners of small and medium-sized farms predominate. By contrast, plantations owned by multinational companies and the country’s large producers – for example, Dole and Grupo Acón – are located in the country’s Atlantic region and account for 28%. The remaining 21% of pineapple growing takes place in the country’s Pacific south-central region, where Pindeco, a division of the Del Monte multinational, is the main player. Since the area under cultivation has essentially remained the same, the increase in pineapple exports is probably explained by the larger yield per hectare, since Costa Rica currently averages more than 80 tons per hectare, possibly the highest figure in the world. In an interview granted to the newspaper La Nación on 7 August 2013, the new president of CANAPEP, Christian Herrera León, stated that the pineapple producers are not planning to increase their area under cultivation and that his organisation is only awaiting assurance by the National Technical Environmental Secretariat [Secretaría Técnica Nacional Ambiental – SETENA], the agency that declares the environmental viability of crops, that two pineapple producers have met all environmental requirements. These statements by the president of CANAPEP were made shortly after residents in the canton of Guápiles organised a demonstration on 5 August 2013 to protest the expansion of pineapple cultivation. His remarks also coincided with a possible end to the ban on further planting of pineapple imposed by the Municipality in this canton in 2010. It has been alleged that there was pressure by the Government to lift this temporary ban. Didier Leiton, Secretary General of the Agricultural and Plantation Workers Syndicate [Sindicato de Trabajadores Agrícolas y Plantaciones – SITRAP], issued the following statement: “In 2013, in light of an appeal for amparo [petition for relief] introduced by CANAPEP to lift the moratorium imposed by the Municipality on the planting of more pineapple in the canton of Pococí, the Constitutional Chamber, through a preliminary report, has indicated to the Municipal Government of Pococí has no authority to declare such a moratorium. The situation, given the clout that the industrial sector has with State institutions and the municipalities, is awaiting final resolution, while in the meantime the pineapple growers in the canton of Pococí continue to be sacrificed.” 9 3. Key Players and their Certification The 'supermarket shelf' data provided by Consumers International partners in Italy, Portugal, Spain, Belgium, Holland and Sweden helped to identify the key brands of pineapples currently sold in these European markets (which is consistent with the data from the 2010 investigation). For Costa Rican pineapples, the main identifiable brands found across all European partner countries were, in order of frequency; Chiquita, Del Monte, Banacol2, Dole and Agricola Agromonte. Other key producers that were not identified in the 2010 investigation include Chestnut Hill Farms and F.lli Orsero de Italia. The main Fairtrade producers are now the medium to large scale Corsicana (Collin Street Bakery) with fewer exports being seen from the Fairtrade certified small farmers association of PROAGROIN (as detailed in section 4.1.) For each of the major European supermarkets, the key pineapple brands (where information on the producer and brand exists) were as follows: Carrefour: Del Monte, Banacol and Dole El Corte Ingles : Del Monte and Banacol Jumbo : Chiquita, Del Monte Dia :Banacol Eroski :Del Monte Lidl : Chiquita There were many other label names that were common across the European market that belong to exporters (which buy from national producers but do not have their own farms) such as Fyffes, Simba, Agroindustrial del Caribe, Capa Oro Dulce and Caribbean Pineapple Export S.A. While data from both the Costa Rican Government and CANAPEP agree that some 1,300 pineapple growers are engaged in production for export, there are only 72 packing plants devoted to the selection and packing of pineapples. The number of packing plants is considerably smaller than the 170 registered pineapple exporters. These figures imply that many of the latter are not only export service companies working for various growers but also pineapple producers themselves, usually certified for quality and compliance with environmental and social regulations. The 72 packers, for their part, function like inbond processing plants, or maquiladoras, providing services for various brands and plantations. This arrangement greatly reduces costs for producers, but it also makes it difficult to monitor the plantations in terms of good production practices and compliance with standards for good labour relations. According to CANAPEP, 70% of the pineapple plantations are certified, but the type of certification is not specified. CANAPEP has its own standards and systems for good production practices. 2 - Banacol is a major banana and pineapple supplier of Tesco for their stores in UK, Ireland, Poland, Czech Republic abd Slovakia. It is likely that by Janaury 2014, Banacol will sign a three year supply contract with Global Food Sourcing/Tesco. 10 The Platform for the Responsible Production and Marketing of Pineapple in Costa Rica in an initiative that seeks to set general standards for production throughout the country. This undertaking will be analysed in detail later in the present report. The Agribusiness Development Program [Programa de Desarrollo Agroindustrial – PROAGROIN] has recorded some 500 small and medium-sized growers in the northern region. This means that many of the growers serve as providers for the 170 registered exporters. Main Producers and their Respective Certifications3 * BCS OKO Garantie and #94011 certified organic [en proceso = pending] On their websites the growers indicate that they have these certifications and have been audited, but the specific plantations, products, and countries are not always clear. Information about who buys the fruit, who markets it, and where it goes is handled as if it was a trade secret. In fact, the plantation owners have warned workers not to make use of the labels for any purpose and that doing so would have legal repercussions. This is what the workers told us in the focus group meeting on 11 August – even though the information is of no interest to the workers and is usually printed in another language. In addition to the voluntary certification schemes such as SA8000, Rainforest Alliance, Fairtrade and Organic, some Costa Rican producers are audited directly by European supermarkets to ensure compliance with quality and production standards and, less commonly, social standards. This is particularly the case with producers that are supplying company and retail members of the Ethical Trading Initiative - a UK based alliance of national and multinational companies (supplying the UK market) that have committed to adhere to the ETI Base Code of Conduct4 and carry out second party (inhouse) or third party (external) social audits of suppliers to ensure compliance. Tesco, founder members of the ETI, are one of the only major European supermarkets that have taken on an approach that goes beyond the standard reputational risk management towards compliance with their own code of conduct – and in the case of the UK retailers the ETI base code of conduct - with Costa Rican pineapples suppliers. Currently the ETI initiative, and therefore that of its members, which focuses on labour standards and therefore direct and visible contact with producers and their workers during social auditing procedures is unfortunately not a common phenomenon across European supply chains. There are however similar initiatives in northern Europe, including Norway, Denmark and an emerging initiative in the Netherlands. 3 List of exporters-producers and their respective certifications for which information was found on the Internet and for which information was obtained in the course of the study. 4 Link to ETI base code 11 Although the UK is not the focus of this report, the relative awareness and concern of British consumers5 - at least as far as retailer perceptions are concerned - means that, particularly in international fresh produce trade chains, the UK leads trends relating to ethical compliance. This drive for greater technical quality (including pesticide use and residues) and social/labour standard compliance is impacting on pineapple supply chains to continental Europe, but also to North America and beyond. The enforcement by retailers of their written policies in this area therefore depends on consumer awareness and the individual retail company's perception of - and reaction to - pressure to change. 5 Deriving from 15 years of public campaigns targeting British retailers and urging them to take responsibility for labour standards in their supply chains. 12 4. Impact of the Pineapple Agro-industry in Costa Rica 4.1 Weakening of the small producers sector The PROAGROIN initiative was originally financed with funds from a debt conversion agreement between the governments of Costa Rica and the Netherlands in 2001. The project created a mechanism to provide technical and marketing support for exporting the products of small growers in the northern region. It led to the creation of an association of these small producers, the Association of ProducerUsers of the Northern Zone Agro-industrial Development Program – ASOPROAGROIN], more popularly known as AGRONORTE. PROAGROIN provided incentives to market pineapple products under fair trade conditions and using organic practices. According to the interview with Mr Sánchez, director of PROAGROIN, since 2008 pineapple cultivation has been affected by a number of external factors: the international crisis of 2008 that kept prices for fruit in general at a standstill and then caused them to decline; the fall in the exchange rate relative to the dollar; the natural flowering of pineapples, attributed to climate change, which affected planting and harvest times; and the stagnant fair trade market in Europe and North America. These changes affected many small growers who, through debt conversion agreements between the governments of Costa Rica and the Netherlands, were available to extend credit to the small pineapple growers. It was possible to adjust the debts, but the market didn’t grow, and a second debt conversion was not possible because of national credit policies, which are very strict. Unable to become economically solvent, many small growers began losing their crops and their land. Faced with this situation, which was generating social unrest throughout the country, 526 of them were forced to stop growing pineapple. PROAGROIN, as a marketing and technical assistance organisation, has encouraged the affected growers to plant other crops such as beans, papayas, or bananas, but strong political will to back up this effort is lacking. In the process of preparing the present report, interviews were held with a group of small producers from this association in the northern region who were filing a complaint against PROAGROIN, since they feel they were duped by the promise of riches to be had from growing pineapple. They are now deeply in debt, and worse, they believe their debts were brought on deliberately. Interviews were held with these disaffected growers and their testimony is included as background for the present study. 4.2 Wages According to government statistics, monthly expenses for a typical family of four in the Costa Rican countryside averaged €223.74 in 2013, up from the 2010 estimate of €171.25. For the average unskilled worker, which would correspond to the rural farm worker, these expenses represent 72% of the official average wage. An analysis of the pay slips of labourers working on three different plantations – Piñas del Bosque (Dole), Hacienda Ojo de Agua (Del Monte), and Saint Peter de Pindeco S.A (Del Monte) – showed that the 13 average daily wage in August 2013 was C8,630 (€ 12.68). In 2010, the average daily wage for workers in various activities was C 8,133 (€ 11.94). The daily wage for a farm worker in Costa Rica for both light and heavy labour is C8,619 (€12.69), which means that the average amount paid on the plantations in this study is similar to the average national wage. However, the salary for heavy labour – and in this case the work of planting, weeding, bedding, and harvesting on pineapple plantations in the circumstances and under the climate conditions where pineapple is planted should be regarded as heavy labour – the average workday, according to a ministerial decree, should be six hours. Since the labourers in question are working eight hours and longer, their real salaries are actually lower, which means that they have to work harder to earn even a bare minimum wage. In the focus group that met on 11 August, the workers said they are not earning a fair wage because of the hours they work, whether employed or on a piecework basis, and their situation is getting worse. This is evident when we see that the government’s calculation of the average monthly cost of living rose 30.65%, while the average daily wage only went up 6.1% during the same period. Interviewees from four different plantations indicated that they have information, or in some cases their foremen have told them, that the companies or plantations set wage budgets per hectare and the foremen are required to stay within these limits. If one or several field workers exceed that fixed amount and earn more money, they are assigned to other tasks in order to stay within the established budget. The 2010 report already noted that when workers are on the verge of meeting higher work quotas, and therefore earning more wages, they are reassigned to some other activity. According to the focus group, it is rumoured that the foremen earn bonuses for staying within the budgets. This explanation for why they cannot earn higher wages is supported by the observation that wages only vary within certain ranges. Also, even though pineapple growing involves production peaks at different stages of the harvest, when more work is required, the increased activity is not reflected in the workers’ earnings or wages. Shift work is organised by the foreman into two or three shifts, which may have to work on rest days or holidays if harvesting needs to be intensified. The fact that contracts are typically given for three to six months, usually with a month in between before the worker can be hired again, may have to do with adjusting the budgets for expenditure on wages. In 2012, inflation was 4.55%, a significant drop from 2008, when it was in the double digits, i.e., 13.4%. However, there are problems in acquiring goods and services. While on the one hand prices for petroleum and certain services under tight government control are kept low, the cost of food and the mass consumer services most used by the population continue to rise.6 4.3 Impact on health 6 http://www.bccr.fi.cr/publicaciones/politica_monetaria_inflacion/Informe_inflacion_junio_2013.pdf 14 We have not seen or heard any evidence of changes in health practices or occupational safety in the plantations. On the subject of protective gear, the same problems continue to exist. In some cases, workers still have to pay for their protective equipment, while in others the company may provide it; however, if it gets damaged, the companies are slow to replace it and sometimes the worker has to pay out of pocket to replace such items as gloves, boots, glasses, hats, or even working tools like files and knives. As reported in 2010, there is still insufficient equipment to protect against high temperatures in the environment, leading to dehydration and fatigue. The 2010 report referred to charges for protective gear. On this subject, the focus groups had the following to say: Saint Peter plantation (Del Monte): “The problem is that the masks were not assigned to us personally, but now they have changed that.” San Carlos Plantation (Banacol): “Yes, the workers have to buy their equipment. The company doesn’t give it to them because it is in debt to the providers. But it’s possible, since the plantation is constantly letting people go, that they don’t want to make these investments and are passing on the cost to the workers. They have given the equipment to the workers who have a long record with the company (about 30 of them) but not the new ones (about 100).” According to Osvaldo, leader of SINTRAPIFRUT [Sindicato de la Piña] in the northern region, who organises workers on the Muelle plantation (Dole): “For the most part, Dole employees work in shifts, but at Agrícola Agromonte, which is a joint national and Dutch venture, and on the Del Monte Providencia plantation, a national undertaking, as well as on the small farms, there is no set working day. People work 365 days a year; they start at 6:00 a.m. and don’t know when they’re going to go home. Often they don’t get social security and aren’t paid for overtime.” Other workers said that their company may provide their equipment, but when it gets damaged they are slow to replace it and sometimes the worker has to pay out of pocket to replace such items as gloves, boots, glasses, hats, or even working tools like files and knives. As reported in 2010, there is still insufficient equipment to protect against high temperatures in the environment, leading to dehydration and fatigue. As for handling chemicals, workers in the focus group report that some plantations are using substitutes for bromacil, but they do not know what the new chemicals are. The usual practice on plantations is for the chemicals to be delivered already prepared and/or without the manufacturer’s labels. The practice of applying chemicals on pineapple plantations is largely cloaked in secrecy. If medical treatment is needed, a worker is not likely to report that he or she has been exposed to chemicals. Pineapple growing still does not inspire trust, especially in communities that farm other crops or raise cattle near the pineapple plantations. It is an issue that has won the attention of a number of other sectors, and its effects on human health and soil conservation have been an ongoing concern for environmentalists and political opinion-makers. 4.4 Unionization 15 Pineapple workers belong to four main unions in the following plantations and agribusinesses: Agricultural and Plantation Workers Union (SITRAP) - 60 members in: Babilonia plantation, Del Monte Development Corporation. Location: Siquirrés José Fina plantation, Pelón National Enterprise Group. Location: Siquirrés Hacienda de Ojo de Agua plantation, National Enterprise Group. Location: Siquirrés Produfrutas del Atlántico, National Enterprise of Colombian Owners. Location: La Rita Pococí Piñales del Caribe plantation, Grupo Acón National Enterprise. Location: Rio Jiménez de Guácimo Saint Peter plantation, Del Monte Development Corporation. Location: La Rita Pococí Piñas del Bosque S.A. plantation, Standard Fruit Company of Costa Rica, Dole. Locations: Guácimo and Roxana de Pococí Piña Frut, S.A. plantation, Grupo Acón National Enterprise. Location: Roxana de Pococí Heredia Agricultural and Livestock Workers Union [Sindicato de Trabajadores Agrícolas y Ganaderos de Heredia – SITAGAH] – 102 members in: Piñales de Santa Clara S.A. plantations (provider for Del Monte) INDACO Horquetas S.A. plantation enterprises (provider for Dole) Collin Street Bakery Corsicana (provider for Dole and Fair Trade USA) San Cayetano de Banacol agroindustrial plantation. Colombia Pineapple Union [Sindicato de la Piña – SINTRAPIFRUT] – 63 members in: Muelle plantation, Dole National Workers Union [Unión Nacional de Trabajadores y Trabajadoras – UNT] – 190 members in: Agromonte S.A. plantation, direct exporter (independent producer) Agrícola Monte la Providencia S.A (independent producer) Once plantation (independent producer) In all, there are 415 affiliated members in an industry of approximately 25,000 directly employed workers. However, each of the above unions do have a much wider membership of pineapple workers, representing a combined total of approximately 2,000 pineapple workers in total on a national level, but these additional pineapple affiliates are either not formally registered as union members with the company (most commonly due to fear of dismissal) or either do no currently work on a pineapple plantation (most commonly due to previous dismissal). None of the unions have signed a collective labour agreement in the pineapple industry, as it is not feasible to get 60% of the union members to opt for collective negotiation. However, the last three years have seen an increase in union activity and the emergence of more organisations. In 2010 only three unions had attempted to organise in the pineapple sector: SITRAP on the Caribbean coast; SITAGAH in Puerto Viejo, Sarapiquí Canton, Heredia; and SITRAPINDECO in the south, where it organised the Pindeco plantations (Del Monte subsidiaries). Later, internal struggles within SITRAPINDECO ultimately led to the formation of a local section of the Public and Private Enterprise Union [Sindicato de la Empresa Pública y Privada – SITPP] in 2010. SITRAP’s Didier Leiton says: 16 “We have heard from a representative of the plantation in Pococí that SITEPP is active there, but it only has a few members. We have not been able to speak to the union leaders since 2011.” In 2006 SITRAP had more than 100 members at Grupo Acón’s Piña Frut plantation, but in 2010 the company managed to neutralise the union. Didier explains: ”However, the fierce campaign that SITRAP waged back then, with a barrage of complaints and campaigns, together with the effect of the lawsuits that it’s now winning, has opened up space for the unions to get stronger. Even though SITRAP and the workers’ cause were weakened and they were hit hard by layoffs, SITRAP is now in the process of resuming its work on the pineapple plantations.” Thanks to these struggles, today new unions are emerging. This is especially true in the northern region (SINTRAPIFRUT) and at the Monte la Providencia and Agromonte plantations, where the National Public and Private Workers Association [Asociación Nacional de Empleados Públicos y Privados – ANEP] was once very active but the workers have now affiliated themselves with the UNT. There is a new national-level federation of agricultural unions: the National Federation of Agribusiness and Related Workers [Federación Nacional de Trabajadores de la Agro-industria y Afines – FENTRAG]. SITAG and SINTRAPIFRUIT are members of this new federation, but SITAGAH and the UNT are not yet involved. Repression of unions: Didier Leitón, leader of SITRAP, reports that, although it is allowed to have members in different plantations, the administrators limit their number. It is now easier for union representatives to visit plantations and workers, and it is also easier to discuss labour issues with plantation administrators. But, according to Didier, there is a reason behind this more open attitude: the companies want to build credibility in order to obtain various types of certification and demonstrate compliance with the codes of conduct. For many years, producers in both the banana and pineapple agribusinesses have been trying to get the good labour practices language for these certifications to state that solidarity associations and permanent committees are admissible or equivalent to unions (see the 2010 report for a full explanation of the solidarity movement). They are also trying to get “direct arrangements” – i.e., lower level negotiations promoted by permanent committees, which can be conducted in the absence of unions – to be recognised as a form of collective labour negotiation. The Costa Rican producers also want the certifications to use the language “freedom to organise” [libertad de organización] rather than “trade union freedom” [libertad sindical] in their guidelines and standards, arguing that the latter is more restrictive and limits the options available to the worker. While it is true that the bodies responsible for SA 8000, the Ethical Trade Initiative (ETI), and general fair trade certifications have vacillated on this subject, they are also feeling international pressure on these points because conventions of the International Labour Organization (ILO) clearly refer to ‘trade union freedom’. [Translator’s Note: This point is nearly moot in English because, while the Spanish title of ILO Convention CO87 is Libertad syndical y la protección del derecho de sindicación, or literally, ‘trade union freedom and protection of the right of unionisation’, the English title of CO87 is Freedom of Association and Protection of the Right to Organise.] 17 It is for these reasons that the companies have opened their doors to unions – in other words, so that they can say that they have granted their workers trade union freedom – although at the same time they have manoeuvred to limit their growth. According to a worker at Piña del Bosque (Dole): “They are on an anti-union campaign, trying to frighten us so we won’t join. They tell us that the company is going to leave. That the plantation has sued the union’s lawyers. The people from the Fair Trade Committee came in together with the Permanent Committee.” At Ojo de Agua (independent producers who sell to Del Monte, among others): “Yes, they are on an antiunion campaign, telling us to resign. The committees haven’t taken any steps to change things in the company, and we are standing up to them. They use their position for personal gain, with scholarships for their children and jobs for their relatives.” Mireya Rodriguez, a SITRAP union promoter, said: “When a union member is elected to the Permanent Committee, the company appoints a replacement.” Cristino, a SITRAP director and pineapple worker, added: ”Some of the workers have been told they were let go because of what the union did. In other cases they won’t hire relatives of union members. This can be proven. They are told that the union is costing the company a lot of money and this is why it can’t hire more people. When a foreman sees that a worker might be inclined to join a union, they let him go before he does.” At Profrut (Banacol): “The Permanent Committee disappeared. A guy came who said that he was from an organisation called ‘Social Peace’ [Paz Social] and his job was to reform the committee. He removed all the leaders from the assembly and replaced them with hand-picked insiders. But they didn’t choose any people from the fields, the processing plant, or the committee’s former leaders.” 4.5 Follow-up of workers’ testimony in the 2010 report a. Pablo López García, Grupo Acón (01-09-2013): In the previous report Pablo, a union member working for Grupo Acon, talked of the health safety risks faced by workers on pineapple plantations. “I was let go at Grupo Acón’s Piña Frut plantation in July 2010. For almost two years I couldn’t get a steady job, and for five months I couldn’t find work of any kind. I think it was because of my activity in the SITRAP union. “A complaint has been filed in the Pococí courts against Piña Frut, the company that let me go in 2010. Because our system is so slow, a decision in this case is not expected until next November. “In Februrary 2012 I was able to find a steady job with El Bosque pineapple plantation owned by Standard Fruit Company of Costa Rica. “I am worried about my current state of health. I have a condition in my nose that makes it difficult for me to breathe normally, especially at night, when I snore a lot. It wakes me up, which is not normal for me. Another problem is that back on 9 March 2010 I went to Social Security with a urological problem 18 because I feel pain and a burning sensation when I urinate. The doctor referred me to the Urology Department at the hospital in Limón, but there they gave me a firm appointment for 3 November 2015 at 10:00 a.m. In the meantime, my condition is getting so much worse that it might be too late to fix the problem. I believe that exposure to chemicals, both at Acón and Dole, are related to these conditions, and I would be grateful if a friendly NGO or other social organisation could help me get treatment in a private clinic, since this would be expensive and I cannot afford it on the small amount of money that I make. I also have a problem that my eyes get irritated by dust from the slips of the pineapple plant. According to information from Dole management, a chemical is applied eight days before the slips are removed. I also have back pain because I worked as a planter for several years. I’m afraid that this pain will get worse by the day and lead to serious consequences for my health. For these reasons, I asked to be assigned to other duties, and now I am distributing planting material in carts.” b. Alfonso – Grupo Acón (01-09-2013): In 2010 Alfonso, a union member talked about the difficulties he had faced as union worker including dismissal from his job for Grupo Acon. Alfonso continues to live in the same house, but he has no steady work. He has not been able to find work on the pineapple plantations, especially in the Grupo Acón, because he belongs to a union. He currently works with a contractor cutting back underbrush with a weed-whacker. The contractor’s name is Carlos Aguilar and he works in the Bandeo neighbourhood. He makes C150,000 every two weeks, and from that he has to cover the cost of gasoline, which is C70,000, so he doesn’t make enough to give his family a decent life. The situation is very critical. c. Testimony of three women: Maria, Mónica, and Anneth The 2010 report contains a declaration denouncing the conditions on this plantation, signed by a group of women workers. One woman on the same plantation said that she had been let go because she was pregnant. Although we did not speak with women on any other Del Monte plantation, we were able to contact some women working for a Del Monte subsidiary. They did not comment on any problems of discrimination or sexual harassment. María Cubillo (12-08-2013): “No legal action was filed with the courts or the Ministry of Labour. We didn’t have any legal advice. Mónica was fired four days after her meeting in San José with the people in ANEP who deal with international companies. “We, Anneth Cubillo and Mónica Chavarría, have not been able to get a job at any Del Monte plantation. Four months after the inquiry, people came from Europe and went to the Ministry of Labour to do an investigation because they had heard that women were not being hired at the San Peter plantation. But by the time that happened we (Mónica and Anneth) were no longer there. The men from the Ministry told Iveth Cubillo that it could not do anything about Mónica and Anneth being let go because they had been dismissed with all their labour rights. “The company retaliated against many of Anneth’s relatiaves: Iveth and Gleydi Cubillo (Anneth’s sisters), as well as the husband of Iveth Cubillo, were all let go.” 4.6 Impact on the community – water pollution in Cairo, Lusiana, and Milano 19 In an interview on 30 August 2013 with Xinia Briseño Briseño, president of the Milan Rural Water Supply Association and vice president of the Siquirrés Environmental Association, she made the following statement: “Since 2010 there has been no significant change, and in fact things have gotten worse. Drinking water services are still being supplied by cistern trucks because the main water supplies, like the system in Milano, are too contaminated for human consumption. Analyses show that the same cocktail of agrochemicals is still being used – the ones that have been poisoning our water for years. “Even the artesian wells are polluted and contaminating the communities: Milano, Luisiana, la Francia Bellavista, and the lower part of Peje, all of them in the canton of Siquirrés. “In June this year the University of Costa Rica and the Regional Institute of Toxic Substance Studies [Instituto Regional de Estudios en Sustancias Tóxicas – IRET] had some analyses done by the laboratories of the Environmental Pollution Research Centre [Investigación en Contaminación Ambiental – CICA], and they continued to find high levels of agrochemicals like bromacil. “Strangely enough, the Water Supply and Sewerage Institute [Instituto Costarricense de Acueductos y Alcantarillados – AYA] also had tests done in April 2013 and they’re saying that the water is not contaminated, but they are still distributing drinking water to the communities in cistern trucks. AYA has threatened that they are going to stop delivering the water in trucks. "The pineapple plantations are still dumping wastewater from the plants into the canals, even though the canals flow back into the water sources. “The responsible authorities aren’t doing anything about this pollution. I am not aware that the government has filed any complaint against the pineapple growers. I am not aware of any complaint of this kind. There are only two complaints: one from the Milano Rural Water Supply Association, which I signed as president of the Association, and another by a neighbourhood committee against Del Monte’s Babilonia plantation, also for pollution. It has been more than three years and nothing has been done. I keep asking questions, and they never give me any answers. They say that only a lawyer can do it. Also, just recently another complaint was filed because fecal coliforms were found in human drinking water. But the complaint mysteriously disappeared; it couldn’t be found in the court files. “A little while later they came to do an investigation. They collected a lot of evidence, but nothing happened. The communities are beginning to see that it’s very difficult to get these companies to obey the law because with their political and economic clout they always get their way in these situations. “Meanwhile, here in the communities we don’t have that kind of clout to file a complaint against the companies that are violating our right to health, to get them to pay and stop polluting. We have good evidence, like the IRET study, to support our claim. The communities are thinking of filing a complaint against these companies. “There is a lawyer named Ruth Solano, but she charges quite a lot. She charges 4,000 dollars to file a lawsuit with the Environmental Court, and 500 dollars for precautionary measures, but the communities can’t pay this kind of money. AYA can’t even charge its normal water rates because the people refuse to pay for the polluted water. Also, the community doesn’t want to contribute any money because the people think that the pineapple growers and the government should be paying for the damage and fixing it, not the community. 20 “Since 2012, AYA has been saying that it’s going to put in new water supply lines and get water from another source, but the landowners are charging too much and the community doesn’t have the money to pay for it. The municipality’s budget is very small, and they don’t even execute it. And through all this struggle, the companies are not offering anything to help solve the problem.” 21 5. Are good practices being followed in labour relations in the Costa Rican pineapple plantations? As it was said before, there is no collective bargaining. All the labour unions mentioned in this report state that there is no dialogue with the companies and there are no mechanisms in place for improving labour relations. From the attitude and behaviour of CANAPEP, it can be seen that this organised sector of producers and exporters for the pineapple industry is obtaining a lot of certifications to create a parallel, voluntary, and ‘self-applied’ system of good production practices. Behind this ‘curtain’ are all the solidarity associations that support, promote, and advise the permanent committees and handle their direct arrangements – in other words, a whole parallel system that over and over again has been deemed to be incompatible with international labour standards, and therefore, international law7. The basic ILO conventions all insist on the importance of good labour relations. For this to happen, the two sides have to be autonomous. But when independent unions can barely operate, or rather, fail to be recognised by the pineapple companies, it is virtually impossible to build or maintain good practices in industrial relations, including collective bargaining. While it is true that many of the pineapple companies, as part of their corporate policy, have supported social programmes that usually have an impact on communities, when it comes to mechanisms for the resolution of labour disputes in which the two sides act independently, not much progress has been made. The following case provides an example: Collin Street Bakery Corsicana is a company owned by United States capital that has been certified by Fair Trade USA and Fairtrade International (FLO). Through FLO, a dialogue was initiated with the SITAGAH union in August 2012 and continued until October of that year. This process produced a series of agreements on such issues as improved eating areas, health services, pay procedures, working hours, health and safety, and meeting space for unions. Not much progress was made on workplace accidents or permission to take part in union activities. However, the agreements provided a basis for follow-up dialogue and produced an interesting document that the union and the company can use for monitoring progress. However, there are no regulations to govern this monitoring; it is crucial to initiate a new process to develop and apply them. The union continues to complain of challenges in carrying out its activities. There have been complaints of union harassment which, despite the terms of the agreements, the union leaders insist is still happening. In 2013, the Labour Court ordered the company to rehire the union workers who had been dismissed over the last two years and compensate them for their expenses and lost wages, and this decision was not well received by the company. What is needed is to open up the doors to dialogue. Recently SITAGAH 7 2010 Internal Technical Report, Section 2.2.f Union Repression, p 25. 22 and the company agreed to start discussing a framework agreement, which could lead to future possibilities for true freedom to unionise and an improvement in labour relations. 23 6. National Pineapple Policy Initiative: Platform for the Production and Responsible Trade of Pineapple in Costa Rica The Platform for the Production and Responsible Trade of Pineapple in Costa Rica is a multi-stakeholder initiative promoted by two key parties: the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) Green Commodities Facility, which supports a project funded by the Netherlands NGO Interchurch organisation for Development Cooperation (ICCO), and the Government of the Republic of Costa Rica, under the leadership of the Office of the Second Vice President, which has assigned a series of tasks to the Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock and the Ministry of Environment, Energy, and Telecommunications. Since July 2013, co-financing of the project has been assumed by the Sustainable Trade Initiative (IDH) with funds from the government of the Netherlands. The idea, as these organisers bring together various groups, including the companies, growers, research centres, etc., is to have a multi-party dialogue on pineapple production and trade. The main goal is to create bases for strengthening standards of responsibility in this industry that will be adopted by all concerned: the companies, the pertinent government agencies, civil society organisations, and workers organisations. In connection with the Platform initiative, a number of working group meetings have been held on specific topics such as soils, agrochemicals, market incentives, and compliance with legislation, producing a list of shortcomings and gaps that need to be addressed by the different sectors. Progress has also been made in the development of a proposed model, which was presented at a plenary meeting in the second quarter of 2013. However, some important areas have yet to be covered. So far, it has not been possible to broach the subject of labour relations because of opposing positions by the unions and the companies. Even though a dialogue strategy is in place, there is no consensus on who should participate. The companies have said that that the solidarity associations (SAs) and the permanent workers committees (PWCs) should participate as well as the unions, but the unions have firmly rejected inclusion of the SAs and the PWCs. The ILO itself, in its administrative and technical resolutions, has excluded the SAs and the PWCs from a possible dialogue. In early 2013 the UNDP asked the ILO Regional Office in Costa Rica to intervene through its Department of Social Dialogue, but according to the unions there has been no progress with this intervention because of the disagreement already mentioned. Moreover, the companies affiliated with CANAPEP have dug in their heels and protested. Its president, Abel Chávez,8 has said that “the pineapple growers don’t need any more models like the ones proposed in the Platform. This Platform should be a mechanism for strengthening CANAPEP and its Pineapple Socio-environmental Commission [Comisión Socio Ambiental de la Piña – COSSAP], because they are the ones who know what the problems are.” 8 A new president of CANAPEP was elected in mid-2013. 24 This is an issue of concern for the future of the initiative, because the aim of the Platform is to encourage broad dialogue with the various parties involved. Perhaps they are unhappy with the direction it has taken, thinking that too many ‘cooks have gotten into the broth’. For this reason, we no longer know for certain how the negotiations and the dialogue itself are progressing. By the same token, the environmental organisations in the communities where pineapple is grown have criticised the Platform from the outset, calling it a ‘green wash' to cover up destructive production practices and an excuse to violate environmental, social, and health legislation9. From the beginning they have refused to participate, claiming that, with these types of organisations, the hoped-for ‘social dialogue’ will be a dialogue without input from organised civil society. The municipal organisations, which have a lot to say, are also holding back. Some of them have even repeatedly declared moratoriums on pineapple growing in their municipalities. However, other groups, such as medium and small producers and organic sectors, have been interested in participating in the Platform, although they are unclear as to how their integration into the process is going to work. In the meantime, universities and government institutions and offices are participating in this space and lending their weight, as well as producers and their associations, with the questionable exception already mentioned – namely, CANAPEP. In fact, there has been active participation by a number of transnational producers and marketers, including Chiquita, Dole, Del Monte, etc.; some supermarket groups such as Walmart and Tesco; certification agencies like Rainforest Alliance; fair trade organisations; universities and other academic institutions; and some community organisations. The Costa Rican Government may see the Platform as one more opportunity to establish its environmental policies that aim for the country to become carbon-neutral by 2020, but there may be some pressure from certain quarters when it comes to coordinating the two ministries that have historically been at odds on how to establish policies in the area of labour. For purposes of the present document, Serna Bonilla, technical adviser on the Platform for the Production and Responsible Trade of Pineapple in Costa Rica, reports that the project has made the following progress so far: 1. A draft National Plan of Action was published in February 2013, representing 18 months of work with the participation of 868 persons from more than 40 organisations from the government, academia, the pineapple industry (small, medium, and large producers), international purchasers, sectoral groups (exporters, producers and formulators of agrochemicals), and community organisations (ADI and ASADAS), who took part in 45 activities, including: 4 presentations by specialists in land use, soil conservation, and integrated pest control; 4 plenary meetings with the participation of representatives from ALL the sectors involved in pineapple production and commerce; 9 http://coecoceiba.org/la-plataforma-para-una-produccion-sostenible-de-la-pina-maquillaje-verde-con-apoyointernacional/ 25 7 meetings to facilitate dialogue between the government, employers, union representatives, and representatives of the permanent committees; and 30 workshops on: a) Enforcement of legislation, b) Use and control of agrochemicals (northern and Atlantic regions), c) Small and medium enterprises, d) Financing and market incentives for responsible production, and e) Land use and soil conservation. The Plan of Action includes the measures identified in the course of this dialogue (please avoid the word 'debate', as the guidelines for carrying out the process refer to a 'democratic dialogue') for improving the environmental and social performance of pineapple production. 2. Following this presentation, the next step was to review the comments and opinions on this draft submitted by representatives of the government, producers, and academic sectors. 3. Once the comments were incorporated into the draft, the list of measures was submitted for technical and legal review and prioritised. Participating in this review were a total of 55 specialists from 25 organisations from the sectors mentioned, who assessed the legal implications and the impact and cost of implementing each measure. This information will be used in the second phase of the project, which will begin once the Plan of Action is officially adopted. It is important to emphasise that economic support from international cooperation agencies has been assured for this new phase. 4. The plan that resulted from this process has now been finalised and is being shared with the Platform participants. It is expected to be made official in the middle of the third quarter (between the end of October and mid-November) under an executive decree that will also create three regional commissions and a national commission that will include representatives of the sectors involved. These commissions will be responsible for overseeing fulfilment of the actions contained in the plan and reporting to the national and international public on its application. How much pineapple production in the country is going to change is still unknown, but it is clear that this initiative is about to be made official by the current administration, which means that it is going to be regarded, or understood, as the national policy on pineapple production. 26 7. Recommendations for Consumer Organisations Potential influencing strategies for Consumers International and partner organisations could include: Increase consumer pressure on retailers towards compliance with social and environmental codes of conduct, policies and national and international legislation along their pineapple supply chains Ensure this consumer pressure is felt – and reacted to – by retailers through engagement in well informed and strategized dialogue and advocacy processes. Promote good practices of ethical compliance amongst retailers using examples such as the Ethical Trading Initiative – and in particular the work of Tesco – and other similar joint retailer initiatives in Norway, Denmark and the Netherlands. Increase pressure on UNDP and the Platform for Responsible Pineapple Production and Trade in Costa Rica, and particularly on its corporate and government representatives, to ensure that social and labour issues are on the agenda. Workers and their independent trade union representatives should be invited to engage actively in the Platform’s dialogue and working groups without having to concede to industry pressure to include unrepresentative workers' organisations10 Join international civil society efforts to get Rainforest Alliance to make systematic Freedom of Association violations an automatic de-certifiable offence. Promote increased supply chain visibility, for example improved labelling systems on the pineapples sold on European supermarket shelves, to ensure that plantation and producer names are available to consumers 10 See 2010 report for further background information on the complexities of industrial relations in Costa Rica due to the existence of Direct Agreements, Permenant Committees and the Solidarismo movement. 27 ANNEX 1: Methodology Followed The data collection and interviews in Costa Rica was undertaken by independent researchers, Omar Salazar and Victor Quesada, with the participation of Didier Leitón, union leader SITRAP. Information and updates on the pineapples sold in major supermarkets in Europe were collected by members of Consumers International organizations in Belgium, Italy, Spain, Portugal, Holland and Sweden. Coordination of research and review of the report was made by Anna Cooper and Alistair Smith, Banana Link. The first part consisted of updating the available information on pineapple production in general in the country, with data obtained from statistical sources and Costa Rican government websites, information sources on the international pineapple trade, and various websites of the producers. The second part was devoted to updating the labour situation through meetings with focus groups. The first round was held from 11 to 16 August with workers and labour leaders from the following pineapple companies in the Atlantic region: Piña Frut and Piñales del Caribe plantation (Grupo Acón): own brand and provider for Chiquita, Fyffes, and Dole, among others Hacienda Ojo de Agua plantation: Bandeco (subsidiary of Del Monte) Saint Peter plantation: Bandeco (subsidiary of Del Monte) Produfrutas del Atlántico: provider for Banacol and F.lli Orsero Piñas del Bosque plantation: Dole Muelle plantation: Dole The content of the 2010 report was presented to the groups and they were asked to give their opinion, focusing on whether or not the events described have been repeated and any significant changes in certain situations reported in 2010. A second round was held on 10 September, in which interviews were held with small and medium producers in the northern region. A visit was paid to PROAGOÍN in Pital de San Carlos and eight small pineapple growers and former growers from Cutrís de San Carlos. The latter sessions were captured on film. A leader and organiser of the SINTRAPIFRUT union was also interviewed. The city of Guápiles in the Atlantic region was visited on 11 September for the purpose of filming interviews and testimony by some of the pineapple workers. The third part involved locating several people who gave testimonials in the 2010 report to ascertain their current situation. In this investigation it was not possible to visit the country’s Pacific south-central region, where Pindeco, division of the Del Monte multinational, is located. 28