A MORAL-EMOTIONAL PERSPECTIVE ON EVIL PERSONS

advertisement

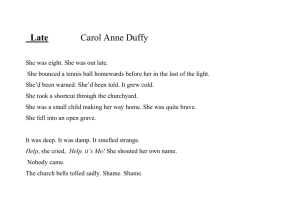

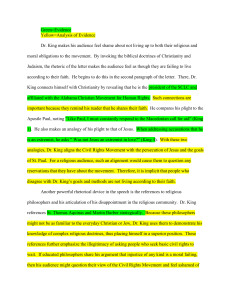

Tangney & Stuewig, “A Moral-Emotional Perspective on Evil Persons and Evil Deeds [Shame & Guilt]” From Miller the Social Psychology of Good and Evil (Guilford, 2005) CONTRASTING THE SHAME AND GUILT EXPERIENCES The terms shame and guilt are often used interchangeably. It is not uncommon, for example, to hear people refer to "feelings of shame and guilt" or "the effects of shame and guilt" without making any distinction between the two. Recently, however, there has been an increase in research examining how they may differ. One idea is that shame and guilt differ in the types of events that elicit them. Analyses of personal shame and guilt experiences provided by children and adults revealed few, if any, "classic" shame-inducing or guilt-inducing situations. Most types of events (e.g., lying, cheating, stealing, failing to help another, disobeying parents, etc.) are cited by some people in connection with feelings of shame and by other people in connection with guilt. Shame involves a negative evaluation of the global self, whereas guilt involves a negative evaluation of a specific behavior. Although this distinction may, at first glance, appear rather subtle, this differential emphasis on self ("I did that horrible thing") versus behavior ("I did that horrible thing") sets the stage for very different emotional experiences… Shame is an acutely painful emotion that is typically accompanied by a sense of "shrinking" or "smallness," and by a sense of worthlessness and powerlessness… Not surprisingly, shame often leads to a desire to escape or hide-to sink into the floor and disappear. Guilt, in contrast, is typically a less painful, devastating experience because the focus is on the specific behavior, not the entire self. One's core identity or self-concept is not under attack. Instead of feeling defensive, people experiencing guilt are focused on the act and its consequences; they feel tension, remorse, and regret over the "bad thing done." People feeling guilt often ruminate obsessively over their action, wishing they had behaved differently or could somehow undo the harm that was done. Rather than motivating avoidance and defense, guilt motivates reparative behavior: confession, apology, and attempts to fix the situation. GUILT IS GOOD, SHAME IS BAD? Over the past decade and a half, research from our laboratory has emphasized the generally adaptive nature of guilt, in contrast to the generally maladaptive nature of shame. One of the consistent themes emerging from our research, and that of others, is that shame and guilt are not equally "moral" emotions. On balance, guilt appears to be the more adaptive emotion, benefiting individuals and their relationships in a variety of ways. Hiding versus Amending First, research consistently shows that shame and guilt lead to contrasting motivations or "action tendencies.” As noted, shame has been associated with attempts to deny, hide, or escape the shame-inducing situation, whereas guilt has been associated with the reparative actions of confessing, apologizing, and undoing. For example, when people are asked to describe and rate personal shame and guilt experiences anonymously, their ratings indicate that they feel more compelled to hide from others and less inclined to admit what they had done when feeling shame as opposed to guilt. Other-Oriented Empathy 1 Second, there appears to be a special link between guilt and empathy. Empathy is a highly valued, pro-social emotional process that motivates altruistic, helping behavior, fosters close interpersonal relationships, and inhibits antisocial behavior and aggression. Research indicates that feelings of shame disrupt the ability to make an empathic connection, whereas guilt and empathy go hand-in-hand. This differential relationship of shame and guilt to empathy has been observed at the levels of both emotion traits (i.e., dispositions) and emotion states. Studies of emotion traits focus on individual differences. When faced with failures or transgressions, to what degree is a person inclined to feel shame and/or guilt? To assess proneness to shame and proneness to guilt, we use a scenario-based method in which respondents are presented with a series of situations often encountered in daily life. For example, in the adult version of our Test of Self-Conscious Affect, participants are asked to imagine the following scenario: "You make a big mistake on an important project at work. People were depending on you and your boss criticizes you." People then rate their likelihood of reacting with a shame response ("You would feel like you wanted to hide"), a guilt response ("You would think 'I should have recognized the problem and done a better job' "). Responses across the scenarios capture affective, cognitive, and motivational features associated with shame and guilt… Researchers have consistently demonstrated that shame proneness and guilt proneness are differentially related to the ability to empathize, a finding that is remarkably consistent across various ages and demographic groups. In contrast, shame proneness has been associated with an impaired capacity for other-oriented empathy and a propensity for problematic, "self-oriented" personal distress responses. ... Anger and Aggression Third, research has shown a link between shame and anger… Lewis first speculated on the dynamics between shame and anger (or humiliated fury), based on her clinical case studies, noting that clients' feelings of shame often preceded their expressions of anger and hostility in the therapy room. Studies of children, adolescents, college students, and adults have consistently shown that proneness to shame is positively correlated with feelings of anger and hostility and an inclination to externalize blame. For example, in a cross-sectional developmental study… proneness to shame was consistently correlated with malevolent intentions and a propensity to engage in direct physical, verbal, and symbolic aggression (e.g., shaking a fist), indirect aggression (e.g., harming something important to the target, talking behind the target's back), all manner of displaced aggression, selfdirected aggression, and anger held in (a ruminative unexpressed anger). In contrast, guilt-proneness was generally associated with more constructive means of handling anger. Proneness to "shame-free" guilt was positively correlated with constructive intentions and negatively correlated with direct, indirect, and displaced aggression. Instead, relative to non-guilt-prone persons, guilt-prone individuals are inclined to engage in constructive behavior, such as non-hostile discussion with the target of their anger, and direct corrective action. In a study of specific real-life episodes of anger in romantically involved couples, shamed partners were significantly angrier, more likely to engage in aggressive behavior and less likely to elicit conciliatory behavior from their perpetrating significant other. Not only were shamed partners more aggressive, but when they confronted their partners, the partners in turn responded with anger, resentment, defiance, and denial, leading to increasingly hostile situations. (1) Partner shame leads to feelings of rage (2) and destructive retaliation, which then (3) sets into motion anger and resentment in the perpetrator (4) as well as expressions of blame and retaliation in kind, 2 (5) which is likely to further shame the initially shamed partner, and so forth - without any constructive resolution in sight. Shame and anger go hand-in-hand. More specifically, desperate to escape painful feelings of shame, shamed individuals may be inclined to react defensively and "turn the tables," externalizing blame and anger onto a convenient scapegoat. There may be short-term gain in blaming someone else and feeling indignant anger, if only because such anger can serve to reactivate the "self" and reignite some sense of control and superiority. Unfortunately, the longterm costs are often steep. Friends, acquaintances, and loved ones alike are apt to be truly puzzled and hurt by what appear to be irrational bursts of anger, coming seemingly out of the blue. IS THERE A TRADE-OFF? DOES GUILT ENHANCE RELATIONSHIPS BUT COMPROMISE INDIVIDUAL ADJUSTMENT? ... Researchers consistently find that proneness to shame is related to a whole host of psychological symptoms, including depression, anxiety, eating disorder symptoms, subclinical psychopathy, and low self-esteem. The findings for guilt and psychopathology are less clear cut. At least as early as Freud, clinical theory and case studies have made frequent reference to a maladaptive guilt characterized by chronic self-blame, and obsessive rumination over one's transgressions. Rather, guilt is most likely to be maladaptive when it becomes fused with shame. When a person begins with a guilt experience ("Oh, look at what a horrible thing I have done") but then magnifies and generalizes the event to the self (". . . and aren't I a horrible person"), many of the advantages of guilt are lost. Not only is the person faced with tension and remorse over a specific behavior that needs to be fixed, but he or she is also saddled with feelings of contempt and disgust for a bad, defective self. In the case of guilt (about a specific behavior), there are typically a multitude of paths to redemption. Having transgressed, a person feeling guilt (1) often has the option of changing the objectionable behavior or even better yet, (2) has an opportunity to repair the negative consequences, or at the very least, (3) can extend a heart-felt apology. Even in cases where direct reparation or apology is not possible, the person can resolve to do better in the future. In contrast, a self that is defective at its core is much more difficult to transform or amend. When the problem is internal, stable, and global, then we have trouble. Linking Moral Emotions to Risky, Illegal, and Otherwise Inadvisable Behavior Beyond psychological adjustment, what are the implications of shame and guilt experiences for the commission of immoral behavior…? There is the widely held assumption that because shame is so painful, at least it motivates people to avoid "doing wrong" and thereby decreases the likelihood of transgression and impropriety. As it turns out, there is virtually no direct evidence supporting this presumed adaptive function of shame. To the contrary, recent research with nonclinical samples suggests that shame may even make matters worse. ... The notion that shame and guilt are differentially related to "moral behavior" is further supported by research on drug and alcohol abuse, aggression, and delinquency. In samples of children, adolescents, college students, and adults, shame proneness has been positively related to aggression and delinquency. In a longitudinal study, Stuewig…found that those high in delinquency and shame proneness at age 15 were more likely to be arrested subsequently for a violent act (according to juvenile court records), compared to those who were high in delinquency and low in shame. Similarly, proneness to problematic feelings of shame has been linked to substance use and abuse. 3 The most direct evidence linking moral emotions with moral behavior comes from our ongoing longitudinal family study of moral emotions. In this study, 380 children and their parents and their grandparents were initially studied when the children were in the fifth grade. Children were recruited from public schools in an ethnically and socioeconomically diverse suburb of Washington, D.C. (Sixty percent of the sample is white, 31 % black, and 9% other. Most children generally came from low-to-moderate-income families. The typical parents had attained a high school education.) The sample was followed up when the index children were 18-19 years old. At that time they participated in an in-depth social and clinical history interview, assessing their emotional and behavioral adjustment across all major life domains. Analyses of these extensive interviews show that moral emotional style in the fifth grade predicts critical "bottom line" behaviors in young adulthood, including substance use, risky sexual behavior, involvement with the criminal justice system, and suicide attempts. More specifically, shame proneness assessed in the fifth grade predicted later risky driving behavior, earlier initiation of alcohol use, drug use of various kinds, suicide attempts, and a lower likelihood of practicing "safe sex." Compared to peers who experienced guilt infrequently in fifth grade, these guilt-prone children were, in adolescence, less likely to be arrested and convicted… In short, the capacity for guilt may foster a lifelong pattern of generally following a moral path, motivating individuals to accept responsibility and take reparative action in the wake of the inevitable, if only occasional, failure or transgression. EVIL DEEDS VS EVIL PERSONS? Thus far, most of the research discussed has focused on the average person's feelings of shame and guilt in response to the failures and transgressions of life. At the heart of this "self versus behavior" approach to moral emotions is the notion that bad (even evil) deeds do not necessarily imply that the perpetrator is a bad (evil) person. Because the vast majority of our research on moral emotions has been conducted on normal, nonclinical, non-identified participants (e.g., college students, elementary school children and their parents and grandparents, airport travelers, etc.), we have generally taken as a given the reality of the "fundamentally good person." Our assumption has been that people's shame reactions typically reflect an overreaction - an unduly harsh assessment of the self based on cognitive distortions inherent in "I did a bad deed; therefore I'm a bad person." In fact, we have reasoned elsewhere that shame is often psychologically problematic, in part, because the leap from "doing a bad thing" (guilt) to "being a bad person" (shame) is typically unwarranted. Are there evil people in the world? This is a question we have mulled over a great deal in preparing this chapter and in reflecting on our recent research experience with incarcerated inmates. In studying evil, social psychologists have long emphasized "the power of the situation." Classics such as Zimbardo's prison study and Milgram's obedience studies serve to remind us that given certain circumstances, the "situation" can induce ordinary, even good, people to commit very destructive deeds. But based on our recent research experience with incarcerated inmates, we have come to appreciate the importance of individual differences as well. Our tentative conclusions are: 1. There are some people whom many would describe as "evil." There exists a costly but reliable and valid measure (discussed in the following material) with which to identify them. Fortunately, even in jails and prisons, such people are a clear minority. For this small group, effective treatments have yet to be found. 4 2. The vast majority of prison inmates are not evil. These are people who have the capacity for moral emotions. They may engage in bad (even evil) deeds, but they are not bad, evil people. The potential for intervention is present. ASSESSMENT OF EVIL Evil is a strong word when applied to behaviors, but even more so when applied to persons. Many people are uncomfortable with the notion of identifying or labeling others as evil. For some, the concern is the strong value judgment inherent in the term. For others, the concern is the heavy religious connotations associated with the notion of evil. Still others worry that the term is damning, implying an intractable trait with no hope for redemption. "What do we gain by using the term evil at all?" asked one of our graduate students. "How does it help us to better understand human behavior to develop an index of evil?" Measures of "evil" are especially relevant in judicial contexts. For example, in making sentencing decisions, judges and juries are often asked by statute to consider the degree to which crimes are "heinous," "cruel," "wantonly vile," or "inhuman." In some cases, such determinations can be a life-or-death matter. Death penalty statutes, in particular, cite numerous aggravating circumstances that can be referred to when arguing a case. The problem is that terms such as heinous, cruel, and wantonly vile are ambiguous in their definitions and are apt to have different meanings to different people. What is cruel to one person may not be cruel to another. Welner has attempted to develop a more objective procedure to measure the degree of depravity, or evil, inherent in a broad range of crimes. Welner's Depravity Scale considers intent (e.g., evidence of planning), nature of offense (e.g. degree of victim's suffering), and the perpetrator's behavior around the time of the event (e.g., indifference), using strict criteria in order to lessen the amount of subjectivity that typically has pervaded courtrooms when evil acts are evaluated. ... Psychologists studying criminal behavior have identified a subgroup of offenders who really do appear to embody the characteristics that most people would ascribe to "evil" persons. According to Robert Hare, one of the leading authorities on psychopathy, "Psychopaths are social predators who charm, manipulate, and ruthlessly plow their way through life, leaving a broad trail of broken hearts, shattered expectations, and empty wallets. Completely lacking in conscience and in feelings for others, they selfishly take what they want and do as they please, violating social norms and expectations without the slightest sense of guilt or regret”… The most extreme examples of psychopathy are those who have become infamous. Ted Bundy, John Wayne Gacy, and Richard Ramirez were all psychopaths as well as serial killers. But the majority of psychopaths are not serial killers; they might kill but only when it serves their interest. They are often impulsive and reckless, unconcerned about whom they hurt, focused more on instant gratification than on any sort of criminal plotting. The "gold standard" for assessing psychopathy is Hare's Psychopathy Checklist-Revised. The PCL-R yields a total Psychopathy score as well as scores on two related factors. Factor 1 assesses the "selfish, callous and remorseless use of others." It taps a personality style defined by people who are glib and superficial, egocentric and grandiose, deceitful and manipulative, display shallow emotions, and are lacking in feelings of remorse or guilt as well as the capacity to empathize with others. Factor 2 assesses a "chronically unstable and antisocial lifestyle," focusing more directly on criminal and other problematic behaviors. Persons who score 30 or higher on the PCL-R are thought to present a qualitatively distinct characterological disorder known as psychopathy. Psychopaths are relatively rare, comprising approximately 1 % of the general population, 15% of local jail inmates, and 25% of state and federal prison inmates… They are 5 largely violent in that they commit twice as many violent and aggressive acts, both in and out of prison, as do other criminals. In fact, 44% of the offenders who killed a law enforcement officer on duty were psychopaths. ... SHAME, GUILT, EMPATHY, AND THE PSYCHOPATH Just what does the moral emotional profile of the psychopath look like? There is surprisingly little systematic data on the moral reasoning or moral emotions of psychopaths. Psychologists and criminologists alike often assume that psychopaths lack any real capacity for moral emotions. Psychopaths lack a sense of remorse and guilt and, more generally, are unable to empathize with others. In fact, impaired empathy and an absence of guilt are two of 20 criteria that define psychopathy, as measured by the PCL-R. But researchers have yet to systematically measure and evaluate the psychopath's capacity for experiencing guilt and empathy. Even less is known about the experience of shame in psychopaths or in incarcerated offenders more generally. Are psychopaths literally "shameless," lacking the capacity for yet a third moral-emotional experience? Or are psychopaths, in contrast, unusually and acutely sensitive to feelings of shame and humiliation-feelings so painful that they turn to delinquent, aggressive, interpersonally exploitative behavior as an escape? ... THE NON-PSYCHOPATHIC INMATE Perhaps the most important single finding in the literature on psychopathy is that the vast majority of inmates are potentially reachable. Approximately 85% of local jail inmates (75% of inmates in state or federal prisons) are not psychopaths; they do not show the combination of behavioral and personality characteristics that mark the true psychopath. They may engage in bad (even evil) deeds, but they are not bad evil people. When they do commit bad acts, they know they have done something bad, and they feel bad about it (even if they do not readily acknowledge these feelings to others). The key question to explore regarding this large majority of current and future inmates is; what kind of moral emotion(s) do they feel? Are they inclined to feel guilt about their specific misdeeds and feel a proactive press to repair and make amends to the harmed person? Or are they likely to feel shame as a person? IMPLICATIONS FOR TREATMENT AND POLICY For most of the past century the predominant model in the field of corrections was one of rehabilitation. This perspective changed during the 1970s and 1980s, when the concept of "nothing works" gained ground based on several reviews of the treatment literature. Recently, due to the development of more sophisticated methods, such as meta-analysis, and tighter control over program implementation, studies have begun to show that rehabilitation can effectively change some offenders. There is now a call for more "evidence-based" corrections' models. As Cullen and Gendreau state, we need to now move from "nothing works" to "what works." An even more important question may be "What works with whom?" In the search for "what works," criminologists and forensic psychologists now emphasize that a "one-size-fits-all" approach is not terribly effective when designing treatment for criminal offenders. What is needed is a better understanding of the key moderators of response to treatment - an understanding of what works for whom. From our perspective, restorative justice-inspired programs may be especially well suited for low psychopathic, high shame-prone individuals. Restorative justice is a philosophical framework that calls for active participation by the victim, the offender, and the community toward achieving 6 the goal of repairing the fabric of the community. For example, the "Impact of Crime" workshop implemented in Fairfax County, Virginia's Adult Detention Center emphasizes principles of community, personal responsibility, and reparation… As inmates grapple with issues of responsibility, the question of blame inevitably arises, as do the emotions of self-blame. Upon reexamining the causes of their legal difficulties and revisiting the circumstances surrounding their offense and its consequences, many inmates experience new feelings of shame or guilt, or both. Another important feature of the restorative justice approach is its "guilt-inducing, shamereducing" philosophy. In early stages of treatment, offenders may feel a predominance of shame, focusing on themselves rather than the plight of their victims. In the long term, restorative justice approaches encourage offenders to take responsibility for their behavior, acknowledge negative consequences, feel guilt for having done the wrong thing, empathize with their victims, and act to make amends. These ideas can also be incorporated into existing jail and prison programs. Therapists and group facilitators can help inmates develop a more adaptive moral emotional style by (1) educating offenders about the distinction between feelings of guilt about specific behaviors versus feelings of shame about the self, (2) encouraging appropriate experiences of guilt and emphasizing associated constructive motivations to repair or make amends, and (3) helping offenders recognize and modify maladaptive shame experiences, in addition to (4) using inductive and educational strategies that foster a capacity for perspective taking and other-oriented empathy. Such programs may be of little benefit to psychopaths, however, who lack the basic building blocks of an effective moral motivational system… Implications for Jail and Prison Policies Aspects of the incarceration experience itself may provoke feelings of shame and humiliation, and it has been suggested that, particularly when punishment is perceived as unjust, such feelings of shame can lead to defiance and, paradoxically, an increase in criminal behavior. As it becomes clear that imprisonment is both extremely costly and ineffective at reducing crime, judges understandably have begun to search for creative alternatives to traditional sentences. The trend toward "shaming sentences" has gained a good deal of momentum in recent years. Judges across the country are sentencing offenders to parade around in public carrying signs broadcasting their crimes, to post signs on their front lawns warning neighbors of their vices, and to display, for example, "drunk driver" bumper stickers on their cars. Other judges have focused on sentencing alternatives based on a restorative justice model (e.g., community service and other forms of reparation), which seem to be designed - at least, implicitly - to elicit feelings of guilt for the offense and its consequences… 7