Women in Celtic Society

advertisement

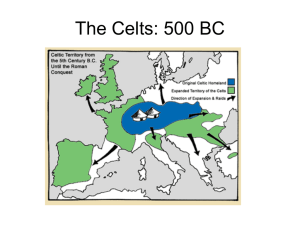

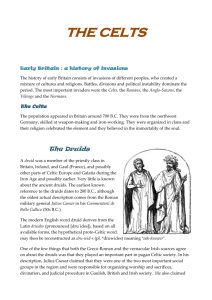

WOMEN IN CELTIC SOCIETY Ancient Celtic society is one of the most fascinating cultures in all of history. Unfortunately, our source material for the Celts is so sparse that much that has been written about it is conjecture, wishful thinking and rumor. As the Celtic scholar Gerhard Helm remarks, “Celts are people who came out of the darkness.” Today, the Irish, Welsh, Scots, Cornish and Bretons in France are descendants of the once populous people of Europe; and the Celtic artistic designs, place-names, and folklore spiral through these cultures. If the colorful author Thomas Cahill is to be believed, the Irish saved civilization, (the name of his best-seller). Paris got its name from the Parisii tribe, Bordeaux from the Burdigala tribe, and Vienna from the Vindobona tribe. Many other important cities and rivers of Europe can also trace their roots to the Celts. It is remarkable that we know so little about the fathers and mothers of Europe who occupied center stage for about 800 years from circa 700 b.c.e. to 100 c.e. The Celts did not have a written language until they were Christianized in the early middle ages. We can thank Julius Caesar who conquered the Gauls for one of our most fulsome historical records of them. A wonderful way to learn about Celtic women is through their own legends. Granted, these stories were not written down until the Irish Celts were Christianized, but not much of the excitement and entertainment appear to have been lost by the inscribing monks. In these myths women are queens, princesses, priestesses, prophetesses, educators, and warriors, many roles of which were normally for males only. Considered the most prominent of their epic stories, the Tain Bo Cualinge = the Cattle Raid of Cuchulainn depicts Queen Medb or Maeve as a powerful, beautiful, and wealthy woman. However, it is in her role as a formidable warrior, that she illuminates the story. Queen Medb or Maeve wages battle against the township of Ulster to gain possession of the prize bull. It is believed that Queen Medb held the de facto power in Connaught. Queen Maeve was so fearsome and powerful that her mere presence deprived her opponents of two-thirds of their courage and strength. Maeve and other Queens received a third of the booty from war, and a third of fines imposed through the penal code, which were exacted 2 in money, jewels or cattle. Until the climactic end of the epic, Medb was the equal of the protagonist hero Cuchulainn, (who by the way was tutored in combat skills by an otherworldly woman, Scathach. Then Medb gets “her gush of blood; and had to leave her war chariot. Cuchulainn came up behind her and captured her. The scene of the defeat is called Foul Medb. Another important aspect of the Tain is where Cuchulainn falls in love with a woman. Discussed first are her intelligence and character. Only tertiary revealed is her beauty and reputation as being the fairest maiden in all the land. Clearly, not the order proscribed in other stories and other time frames. The Celtic social structure was like most other ancient ones. Tribal chieftains made up the aristocracy. Aristocrats were ennobled either by birth or by accomplishment, usually as warriors. Powerful priests and priestesses known as druids also were aristocrats. Well-off farmers, bards, and highest-ranking artisans such as blacksmiths made up the next layer of society. On the bottom were the labors, serfs and slaves. Women were represented in each of these three main categories. What is so remarkable about the laws and customs of the Celts is that there is an equality and harmony between men and women that were unique except for the ancient Egyptians. Women enjoyed widespread sexual freedom, and a woman even had the right to choose her husband, or what is more remarkable could choose not to marry. A woman could not be married without her consent. A great feast was organized at a propitious time of the year where all young people were invited. A young maiden would offer to wash the hands of the man of her choice. Cosmetics were used by the Celtic women, and one Roman poet reviled his mistress for “Making up like the Celts.” Some women even took more than one husband. In Wales the husband-to-be paid the cowyll or virginity fee on the night before the marriage was consummated, whereby in Germany it was given only on the morning after = the morgengabe idea. While the husband appears to have had dominant authority over his wife (at least according to Julius Caesar) the husband was not always the dominant marriage partner. If the 3 wife had a greater fortune than her husband then she was the head of the family. In Brittany women today still retain great moral authority and are often head of the family. An old custom in Irish and Welsh literature, the children were named after their mother and not their father. Yet in some areas, and here the assumption is Celtic tribes closer to Germanic ones, then a wife could be killed for adultery, if the death of a man awoke suspicion. Divorce for the ancient Celts was similar to our customs today. It was always easy for both the husband and wife. If the husband was guilty of adultery, then the wife could immediately obtain dissolution of the marriage. Both polyandry and polygamy appear to have been practiced, although having more than one husband appears to have been more common in Scotland. Concubinage was practiced, but the lawful wife could refuse admittance of a concubine. If her husband overruled her, then his wife could divorce him. In the legend of St. Bridget of Kildare, a druid priest bought and impregnated his concubine. His legitimate wife threatened divorce if her husband did not leave his concubine. The husband gave up his concubine, as it appears he would have lost a lot of money and goods if he failed to heed his wife’s demands. Property was owned equally by both women and men. One of the most unique customs of the Celts compared to other cultures was fosterage. This was a system whereby both girls and boys were sent to foster families around the age of seven to become educated commensurate with the child’s social status. Girls were taught the usual domestic duties, sewing, embroidery, etc., but also the skills of martial arts. The fosterage fees were one-third more for the girls than boys. Girls returned home at fourteen to be betrothed and boys at seventeen. Foster children were expected to provide amicable bonds between the families to help eliminate warfare. Not only legends but real events indicate Celtic women fought alongside men in battle. The Celts rushed into battle, blowing their tall trumpets and emitting blood-chilling war cries. With severed heads of their enemy slung from their horses’ bridles, “Roman writers were impressed with Celtic women - “Gallic women are not only equal to their husbands in stature but 4 rival them in strength as well;” “A whole troop of foreigners would not be able to withstand a single Gaul if he called to his assistance his wife, who is usually very strong and with blue eyes.” There are several famous warrior queens. Perhaps the most famous, at least from the English perspective, was Boudicca. When her husband Prasutagus died, who was king of the Iceni, one of the leading tribes of East Anglia, Boudicca assumed the queenship. Her husband had left half of his estate to his two daughters and the other half to Nero and the Roman Empire to ensure his family would be honored and protected. When the Roman officials carried out the necessary inventory of the estate, they acted arrogantly and refused to honor Boudicca’s new position. Furthermore, they reduced the status of the Iceni kingdom. When Boudicca objected the Romans flogged her and then raped her two daughters. Boudicca was able to arouse much support and sympathy with the neighboring tribes and the Celts in England went to war against the Romans. A wonderful description of her survives from the historian, Cassius Dio’s 3rd century work: “She was enormous of frame, terrifying of bearing and with a rough shrill voice. A great mass of bright red hair fell down to her knees; she wore a huge twisted torque of gold, and a tunic of many colors, over which was a thick mantle held by a brooch. When she grasped a spear, it was to strike fear into all who observed her.” In a short time the ferocious fighting flared, she and her warriors sacked Colchester, an important Celtic center that the Romans had taken over, and then London, the most important Roman city in England. It looked as if Boudicca was to be victorious, but then the Celtic warriors did not stay focused against the Roman soldiers. Rather than suffer a humiliating death when the war appeared lost, Boudicca took her own life with poison. A Victorian statue of this heroine stands near Parliament. This event is so famous to the English that when Margaret Thatcher was Prime Minister in the 1980’s, cartoons depicted Margaret as driving her chariot just like Boudicca had done about 2000 years earlier. Celtic religion is a fascinating mix of legend and lore, and much of their religious customs survived when the Celts were Christianized. There appears to be over two hundred deities, composed of both gods and goddesses. Druid priests and priestesses oversaw the 5 religious rituals intended to propitiate the gods and goddesses. Nearly twenty years were required to become a druid. Upon completion of their apprenticeship, the druids became peripatetic priests, moving from tribe to tribe. Judicial and legal responsibilities were also included in their duties. Reverence for the human head, sacredness of mistletoe, oak trees, fire and water, life after death, and triple aspect are some of the characteristics of Celtic religion. Today’s leprechauns, bon fires and mistletoe still resonant with our festivals and fancy. Several Celtic goddesses can be connected with the earth mother, taking us back to mother nature. Perhaps the most celebrated one is Brigit. Her identity and titles changed over the years, but she was so beloved by the Celtic people that she became St. Brigit for the Irish Catholics. She was possibly the mother or daughter of the original Tuatha de Danann, otherworldly group of people who invaded the ancient land of Ireland. Tuatha de Danan means children of Danu, who was a mother goddess. Bridgit will also be referred to as the triple goddess, mother goddess, virgin mother, and virgin saint. Her totems are the cow, serpent, sheep, sun moon, sacred fires, and perhaps the most controversial, Sheela-na-gig, a goddess holding wide opens her womb. In this position she is found carved on top of the entrance to the Church at Killinaboy, with the idea that the congregation if entering God’s church through her womb. Mythologist, Robert Graves, elucidated the triple aspect for goddesses into maiden, mother and crone, and Bridgit portrayed all these aspects. Brigit was the patroness of many areas: cultural development, the arts, science, domestic skills, fertility, healing, and metalwork. There are temples all over Europe to her, and not just in Ireland. Her festival is known as Imbolc, where the lactation of the ewes begins and winter ends, February first. Brigit is represented on her day by a corn doll. Young girls are dressed in white and then proceed to a special feast. Earlier times probably saw the advent of ritual mating ceremonies, similar to the May Day rituals. When the Catholic Church found Brigit’s cult impossible to eradicate, Bridgit became a saint. Her day of celebration was called Candlemas, but still celebrated on the first of February. Further legends 6 extend Bridgit’s roles in history to the midwife, foster mother and then mother of Jesus. Eventually, Celtic Christians turned the trinity of father, son and Holy Ghost into the triad of Brigit, Patrick & Columbus: mother, father and holy dove. When a double monastery was established on the site of the pagan temple to Brigit at Kildare in Ireland, nuns kept vigil over a fire that was never allowed to go out, recalling the Vestal Virgins of ancient Rome in their duties of keeping the perpetual fires burning too. Another important goddess for the ancient Celts was Epona. She was a horse-goddess even venerated by the Roman cavalry, who helped spread her cult. Epona was officially honored in Rome with her own festival. Riding side-saddle in most depictions of her, Epona was also sculptured carrying a cornucopia. In a famous chalk carving into the English landscape, Epona may be depicted as the White Horse at Uffington. Cerridwen was a Welsh goddess of dark prophetic powers. She is keeper of the cauldron of the underworld, and some think she is the origin of witches and cauldrons of later times that have come to imbue our culture re Hamlet and Halloween. Like the ancient Greeks with their worship of Athena, the Celts had a war goddess too. The Morrigan or phantom queen appeared in triple form too. In these other two parts, her name meant frenzy and a crow or raven, what became birds of evil throughout later history. It was important to have the Morrigan on your side if you hoped to win the battle. Another warrior goddess, Andraste, was invoked by Boudicca when she revolted against Rome, but not much is known about her. Arianhod was a goddess of rebirth, and fertility. She is usually depicted nursing twins. Another deity related to fertility was a male. The ancient Celts carved out of the chalk hills an eighty foot image of him with a prominent male gender piece. Barren women apparently spent the night sleeping on him in hopes of becoming pregnant. Usually thought of as being atypical was a sun goddess, but in many ancient cultures like Japan, the Hittite Empire and the Celts, people worshiped the sun as a goddess. In England it was 7 Aqua Sulius, where the famous Roman spa of Bath was once the shrine for Sulius. Later on when the Romans occupied England it became a shrine for Minerva.