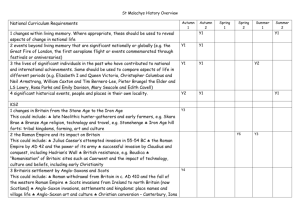

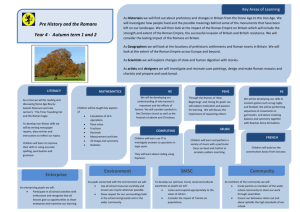

Late prehistory and the Roman archaeology of Britain south of the

advertisement